As the 1960s began, Sammy Davis Jr. was one of the most revered and highly paid live entertainers in America. He headlined in Las Vegas. He starred in prime time variety specials. He had even broken ground as a Black leading man in several dramatic television shows.

But as Davis — who would have turned 100 on Dec. 8 — put it, he wanted to “bust out.” His Rat Pack bromance with Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, among others, was strained, what with their increasingly racist put-downs during their Vegas gigs. Davis was also still holding up his decades-old contract with the Will Mastin Trio, the song-and-dance act with his father and godfather that helped make him famous. Now the act seemed ludicrously out of step with the times.

“Sammy felt as though his musical and dancing credentials were all there,” recounted the composer Charles Strouse in an interview for the American Masters documentary “Sammy Davis, Jr.: I’ve Gotta Be Me.” “What he wanted was to work in the thea-tuh.”

The Broadway producer Hillard Elkins had caught Davis’s act at the London Palladium in 1961, and was immediately inspired to option Clifford Odets’s 1937 drama “Golden Boy” as an updated musical vehicle for the performer.

“In the original play, the principal character, Joe Bonaparte, a struggling young violinist who becomes a prize fighter, was an Italian American,” Elkins wrote in a souvenir program essay. “It seemed to me that an alteration to fit the political realities of the 1960s would be to make that protagonist a young Black man.”

When Elkins pitched the idea of a contemporary musical adaptation directly to Odets, who was living in Hollywood, he declined — until Davis was suggested as the lead. After Elkins tracked down Davis, he responded: “I love it — I’ll be ready whenever you are.” A serious theater role was the “bust out” Davis had been waiting for — he gave up a salary of $35,000 a week in Vegas to appear on Broadway for half that paycheck.

Two elements would proclaim that this “Golden Boy” was going to be a breakthrough for Broadway and for Davis. First, it was a tragic interracial romance in a Broadway musical, as the female lead was white (as was May Britt, Davis’s wife at the time, who died this month). And Sammy Davis Jr. would leave his father’s act behind, billed for the first time simply as “Sammy Davis.”

Davis had actually done a Broadway musical with the Trio before — “Mr. Wonderful” in 1956, a hoary backstage tale of a nightclub entertainer — but the dramatic challenges of “Golden Boy” were far more considerable than anything Davis had ever tried. He and Odets had initially gotten along famously, but Odets had trouble transforming his play into a musical. Joe Bonaparte had become Joe Wellington (a sly reference to, of all things, the Battle of Waterloo); however, the artistic profession that conflicted with his prizefighting ambition changed all the time.

“I played so many different careers,” Davis told his biographer Burt Boyar in a 1986 interview. “They made me a pianist, then a surgeon. I didn’t know what I was playing from one night to the next.” The script’s confusion intensified when Odets died in August of 1963 before the show went into rehearsal.

The show’s first director, the Englishman Peter Coe, was let go, which was fine with Davis: “He didn’t know what was going on in America.” He was replaced by Arthur Penn, an Actors Studio alum, who had made his name with “The Miracle Worker.” The author of that work, William Gibson, was brought on board as Odets’s replacement during the Boston tryouts. Gibson focused Joe’s conflict by channeling the professional and personal travails of another prizefighter in the headlines: Cassius Clay, soon to rename himself Muhammad Ali.

“The denial of his Blackness is [Joe’s] conflict; his Blackness is his hands,” Davis observed about Gibson’s take: “Joe wants to give up his background to be part of the power structure.”

Davis was also in sync with his songwriting collaborators, Strouse and the lyricist Lee Adams, who were fresh off a hit (“Bye Bye Birdie”). Often flying to Vegas to audition material for Davis at three in the morning, the duo tailored songs to Davis’s own experiences growing up as an ambitious young man from Harlem: “Because in many ways this was Sammy’s story, too,” Strouse said. In the opening, “Night Song,” Joe sings from a Harlem rooftop, gazing yearningly at the bright lights of downtown: “What do you do when you’re filled with this feeling of rage? / Who do you fight when you want to break out? / But your skin is your cage?”

A more difficult musical number emerged in the second act when Joe and his manager’s girlfriend, Lorna (played by Paula Wayne), consummate their repressed passions for each other onstage. “Their duet, ‘I Want to Be With You’ was probably the most important song we had ever written because it was a moment which had never happened in the American cinema, television or on the stage,” Strouse said.

In the 1986 interview, Davis recalled debuting “I Want to Be With You” during the tryout in Detroit, a city that had been a hotbed of racial tension following a police shooting months earlier. “We didn’t even touch each other; I was scared of it. And what Arthur said was, ‘I’ve never seen a love scene in my life where people don’t hold hands: hold hands, kiss — do something!’ So at the end of the song, we grabbed each other and kissed, and it was the first time that a man and woman of different races had done that on the stage, full on the mouth, in Dee-Troit, Michigan.” Davis — usually the coolest cat in the room — admitted he was petrified.

During that moment, there was a gasp in the audience at the Fisher Theater, and Wayne subsequently received threatening letters; she and Davis were given bodyguards throughout the out-of-town tryouts and even on Broadway. Outside the Majestic Theater, a billboard with a promotional photo of Wayne and Davis embracing was defaced.

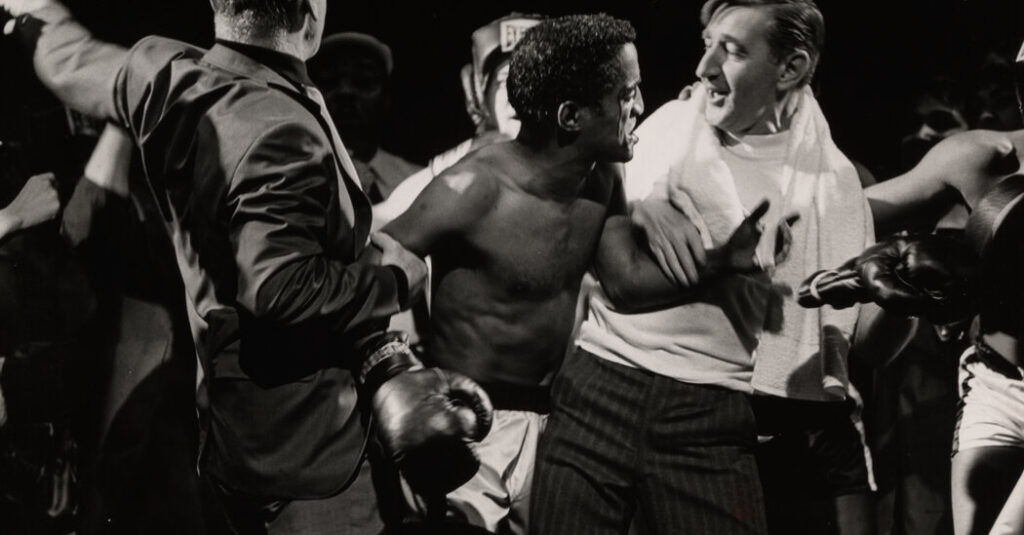

The role of Joe Wellington was an almost unconscionable load for any performer, even one with Davis’s protean talents — nine songs, and a choreographed prize fight at the conclusion where Joe accidentally murders his opponent in the ring. But perhaps Davis’s greatest challenge was transforming himself into a serious actor.

Paula Wayne recalled: “Arthur Penn said, ‘Sam, I want you in your dressing room at half hour and I want you to prepare.’ And Sammy said: ‘Prepare? What, I put on my makeup?’ And Arthur Penn looked at him and he went, ‘Oh my god, I’ve got the most expensive show ever put on Broadway, and my star doesn’t know how to prepare!’”

Eventually, Penn advised Davis to trust his own instincts, but the pressure of the $600,000 production on the star became too intense: Two days before the show’s opening on Oct. 20, 1964, Davis flipped out, skipped the Saturday matinee and evening performances, and hid out in a friend’s apartment. Elkins was given the unenviable task of explaining his star’s absence to disappointed patrons.

Much to everyone’s relief, Davis reappeared in fine shape for opening night, and five of the city’s six papers were near universal in their praise: “Sammy Davis in a Knockout,” went the headline in The Journal-American, and The New York Herald Tribune review from Walter Kerr announced: “Mr. Davis is on top of a new situation, licking it hands down. His performance is serious, expert, affecting.”

“We broke new ground on Broadway,” Davis recalled. “You knew you were in something important, we struggled and we won.”

Davis kept at the demanding role of Joe Wellington for almost 600 performances (all while writing his first memoir, “Yes I Can” — titled after a song cut from the show). The star did cancel a matinee in March of 1965, when Harry Belafonte convinced a reluctant Davis (who had never traveled south of the Mason-Dixon line) to sing at a pro-civil rights concert in Selma. Davis continued off and on in Chicago and London productions of “Golden Boy” into 1968.

With his characteristic intensity of commitment — yes, he could — Sammy Davis achieved everything he had set his sights on with “Golden Boy.” “I was as hot as I could be in my hometown,” he said. “I was on top of the world, there was no door that wasn’t open to me: I was the Prince of Broadway.”

The one meaningful achievement that eluded him, perhaps, was a Tony Award: “I was up against a gentleman named Zero Mostel, ‘Fiddler on the Roof.’ Timing, man. Timing is everything.”

The post When Sammy Davis Jr. Knocked Out Broadway appeared first on New York Times.