Anti-Trump activists are deploying an array of tactics to fight back against the policies of the President and his Administration — protests, marches, events, advocacy campaigns, social media videos. But success requires thinking broadly, and the history of the civil rights movement suggests that there is one uncommon realm for activism which could provide them with a boost: the kitchen.

In 1955, civil rights activist and cook Georgia Gilmore (1920-1990) took to her kitchen after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) launched the Montgomery Bus Boycott. An active member of the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) chapter and well-known for cooking and selling food to raise funds for her church, the boycott presented Gilmore with the opportunity to amplify her talents. For 381 days, she transformed her simple home kitchen on Dericote Street in the cradle of the Confederacy into a battle post for the boycott.

Her weapons: fried chicken, sweet potato pies, pound cakes, fried fish, stewed collard greens, and stuffed pork chops. On the surface, this sounds like a menu of soul food delicacies. But in the hands of Gilmore, and a covert network of Black women cooks she called the “Club from Nowhere,” these foods reconfigured the landscape of public transportation in America, opening up a pathway for all Americans to ride buses.

Gilmore was born in 1920 on a small farm in Montgomery County, Ala. She grew up raising hogs and slaughtering chickens for food. Like many Black women in the rural Jim Crow South, Gilmore watched her mother and other women in her community convert these provisions into fried chicken, pork chops, and other staples. Their kitchens served as a network of classrooms in which Gilmore received culinary training in southern cuisine.

Read More: The Story of the Voting Rights Act Is a Lesson in Overcoming Setbacks

By the 1950s, cooking offered Gilmore one of the few professional opportunities available to Black women in the South, and she had become the top cook at the popular, whites-only National Lunch Company in downtown Montgomery.

In December 1955, however, everything changed for Gilmore. Police arrested seamstress Rosa Parks after she refused to move to the back of a bus for a white passenger, sparking the formation of the MIA and its boycott. Parks’ arrest deeply resonated with Gilmore.

Three months earlier, a white bus driver had verbally harassed her. After taking her fare, the driver called her a racial slur, and forced her to enter the back of the bus — only to then speed off before she could get on. From that moment on, Gilmore boycotted the city’s buses. Parks’ arrest, however, compelled her to want to do more.

Inspired by King’s call for Black people to use their skills to support the boycott, Gilmore did what she knew best: cook.

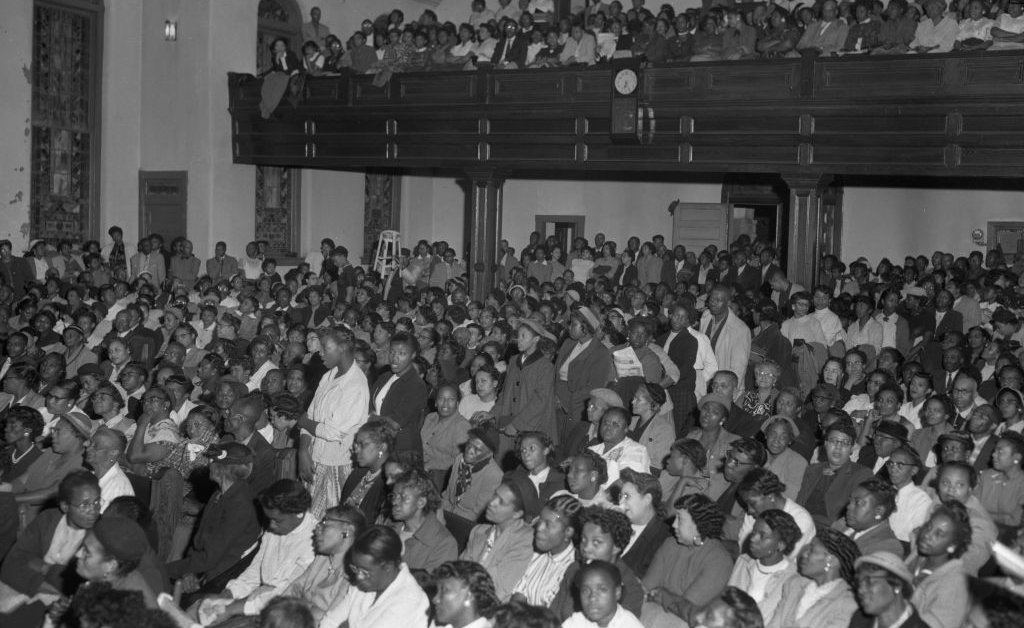

But she didn’t cook alone. Gilmore organized other Black women cooks and enlisted them to join the Club from Nowhere to sell plates and help fund the protest. She coordinated the delivery of the plates to MIA meetings, beauty shops, doctors’ offices, and even cab stands, dispatching her team to secure purchases in support of what would become the longest protest in the history of the civil rights movement.

Stationed in her kitchen, using her stove as a platform, Gilmore practiced what I call emancipatory food power, which was a means for Black people to weaponize food at times of social unrest as a way to protect themselves from oppression. With each pot, cast iron skillet, and cooking utensil, Gilmore exemplified this longstanding tradition in Black life, negotiating her identity in America and resisting the ills of racial segregation that pervaded nearly every aspect of her community.

Gilmore decided to fight racism in the place where she felt most comfortable—and where she felt like she could make the most difference as a Black woman in America—her kitchen. The room became her command center, empowering Gilmore to carve out her own space to think, organize, and act. Others marched and protested in support of the boycott, engaging in high-risk forms of activism that could cost them their jobs. While Gilmore’s activism from her kitchen involved less risk, it still changed the course of the civil rights movement.

As national headlines rightfully celebrated Parks’ courage and the charismatic leadership of King in fomenting and sustaining the boycott, Gilmore continued to cook in quiet obscurity. That was until she testified in court in March 1956 in support of King, who was facing charges for unlawful conspiracy in relation to the boycott.

Gilmore’s testimony shifted the tone of the court hearing, placing a target on her back. Vividly describing her encounter with the bus driver in October 1955, Gilmore called city bus drivers the “meanest, nastiest” people in the world. “I decided then and there not to ever ride a bus again,” she concluded. The next day, a photo of Gilmore between King’s attorneys appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier with the caption: “Trial Figures—…One of their key witnesses, Mrs. Georgia Theresa Gilmore, who gave a vivid description of her ‘unpleasant’ experiences with a bus driver.”

Entering the public eye cost Gilmore her job. The National Lunch Company terminated her employment — which was a common practice used by the white power structure in the South to punish civil rights activists. Within a few days, however, she received financial backing from the King family to update her kitchen equipment and turn her dining room into a restaurant.

From that point on, her in-home restaurant functioned as a “situation room” for the boycott and beyond. Top secret conversations about movement strategies and tactics abounded over plates of Gilmore’s food.

Read More: How Tuscaloosa’s ‘Bloody Tuesday’ Changed the Course of History

On Dec. 20, 1956, the boycott finally ended after a year when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional. With the victory, Gilmore disbanded the Club from Nowhere. Yet, that didn’t mark the end of her activism. Gilmore’s in-home restaurant took on a new life of its own. It now served as a meeting place for the movement as struggles for voting rights took center stage, becoming a cornerstone in the system of Black eateries in the South that served as safe havens for activists, including Peaches in Jackson, Miss., Dooky Chase’s in New Orleans, and Paschal’s in Atlanta.

King was a regular visitor, and even after he left Montgomery for Atlanta, he returned to Gilmore’s restaurant in 1965 to eat as he prepared to make his way to the Edmund Pettus Bridge to participate in the Selma March that catalyzed the Voting Rights Act.

Over the next decade, Gilmore’s list of patrons included prominent American figures such as President Lyndon B. Johnson and Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Dignitaries crossing the threshold of Gilmore’s home to eat and discuss the future of the nation’s democracy illustrated why she believed that food could be a tool in helping to redirect America’s trajectory toward an equitable future for all.

Though she never attained fame, without Gilmore’s thinking and sharp culinary skills, the Montgomery Bus Boycott may not have succeeded. The legacy of her kitchen activism offers a way forward as Americans scramble to fight back against an array of Trump administration policies. While some will march or protest, for those less comfortable with those forms of advocacy, they can look to follow in the footsteps of Gilmore — as the Ghetto Gastro, a Black-led Bronx-based chef collective that is fighting systemic racism through emancipatory food power rooted in community, is doing. In embracing food as a tool to fight injustice, activists would be amplifying a tradition that was at the heart of Gilmore’s kitchen.

Bobby Smith II is associate professor of African American studies at the University of Illinois—Urbana-Champaign, author of the James Beard Award-nominated book Food Power Politics, and Public Voices Fellow through The OpEd Project.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.

The post History Shows How Cooking Can be a Pivotal Tool for Activism appeared first on TIME.