When it came into view, Doctor Rustin was struck by its size. The platform rose on six-by-six wooden posts at least 12 feet off the ground, with enough room up top for a small deck party, and the staircase from the sidewalk was a steeply pitched ladder. This gallows had been raised to last—built not only by children but for them, since few adults would have the agility and daring to reach the top. Its height and solidity gave the sense of a play structure, the crossbar that loomed above the platform a climbing feature for the truly fearless, and the rope noose perfect for swinging and letting fly if only the gallows had been built over water.

A drop by the neck from 12 feet into midair would not be play. The designers of the Suicide Spot had been impressively serious. Rustin ran his hand over his own neck and forgot his mission.

About 30 people were gathered around the base, spilling from the sidewalk into the street. Most were teenagers skipping school, though there was a scattering of grown-ups and a couple of families with younger children. High up on the platform, two girls in yellowish-gray clothes stood on either side of a boy. He looked a year or two older than Rustin’s daughter, Selva, with a wild thicket of hair and a tough face. He was tugging at the rope as if to test its strength, eyes narrowed, lower lip jutting out in a kind of defiance, while the two girls leaned close and spoke to him in voices so quiet that Rustin, keeping back and half concealed under the red awning of a tavern called the Sodden Spot, couldn’t make them out.

But he knew they were Guardians—specially trained peers, there to help confused young people break free from life as they’d known it before the Emergency, in particular from their parents, and become unconflicted agents of Together. Mere weeks after the empire had collapsed, that word appeared on posters glued to the walls of public buildings and on banners strung from lampposts along the central avenues. What Together meant as a philosophy or program, Rustin wasn’t sure, but as a passion, it had quickly spread among the city’s Burghers, especially its youth, and created hairline fractures in his family. The Rustins were no longer the tight foursome that played word games at dinner. Selva no longer returned on the tram after school, but instead disappeared into the city, attending the daily gathering in the main square called We Are One, staying out for hours. This morning, Rustin—marooned at home since being exiled from the hospital in disgrace—had followed her through the streets until he lost her in the Market District.

In front of him a bickering couple, huddled under an umbrella—though it wasn’t raining—made it even harder to hear what was happening on the gallows.

“You didn’t have to come,” the woman said. “I could have come by myself.”

“You were afraid to. ‘What if one of them really does it?’ ” the man said, mimicking her panic.

“I never said that.”

“Shh!” Rustin hissed. The Suicide Spot belonged to the young, and he didn’t want to be associated with the disrespect of the middle-aged.

The boy’s shoulders rose and fell. He looked down to check the position of his feet over the trapdoor, then draped the noose around his neck. A murmur that sounded almost like satisfaction passed through the audience.

A Guardian placed her hand on the lever connected to the trapdoor. In a voice clear enough to carry over the crowd, she asked: “Do you want to leave this world?”

Rustin saw the boy’s face tighten. His eyes twitched in rapid blinks, his lips disappeared as if cold fury were coursing through his body. Then his features crumpled and he exploded in tears. He sobbed openly, without shame, like a little child, his whole body shaking. Several times he tried to master himself, but he couldn’t stop.

Keeping a hand on the lever, the Guardian reached with her other and touched the boy’s heaving shoulder. “Hey—we’re here with you. We’re suffering with you. We love you.”

The boy buried his face in his hands, and the thick nest of hair shook as if in a wind, and the sobs, though muffled, grew louder. Sighs of pity rose around the gallows.

“What do you want to say to your parents?” the other Guardian asked.

The boy looked up mid-sob, startled. “My—I—”

“If they were here, what would you say to them?”

He opened his mouth but no words came out, only a stuttering sob.

“This is pointless,” the woman under the umbrella said.

“You were the one that wanted to come,” the man said.

“Why don’t you both leave?” Rustin asked. They turned around to glare, but their talking stopped.

“Mama!” the boy suddenly cried out. “I’m sorry!”

“You have nothing to apologize for,” said the first Guardian, her hand still gripping the lever.

“Do it!” the boy wailed.

The Guardian didn’t move.

“Talk to us,” the other Guardian said. “We don’t want to lose you.”

“Shut up and do it!”

“Talk to your parents. Why are you sorry? They should be sorry.”

“Mama will be when I do it!”

The Guardian on the lever, who seemed to be leading the session, nodded.

“Oh, Mama will be sorry. But what about us? You’re gone, and we needed you. Do you know what’s on the other side of that door?”

The boy looked down at his feet. He shook his head.

“A great big empty hole. When you went through that door, the hole got bigger than you can imagine. That hole is bigger than this city.”

The crowd drew in its breath as if the boy was already dangling broken-necked from the noose.

Rustin tried to imagine this girl and boy talking in someone’s bedroom, which was where teenagers used to have difficult conversations. Talking face-to-face in private was supposed to allow you to open up, but maybe it wasn’t true. Maybe it was easier to say everything like this, with a crowd at your feet and a rope around your neck.

“Please just do it,” the boy said in a voice strained from sobbing, but softer, losing conviction.

“And we were about to try something that has never happened before,” the Guardian went on. “We were going to make a new city! Make ourselves new, too! We were young and dumb enough to think we could do it. How can we now without you?”

The boy murmured something Rustin couldn’t hear.

“And what about your Better Human? All that work you did. What’s going to happen to him now that you’re gone?”

The woman under the umbrella tugged at the man’s coat sleeve. “What did she say? Better what?”

“How the hell should I know?”

Rustin didn’t understand either.

The Guardian went on talking while the boy listened. He began to nod, and after a few more minutes he lifted the noose off his neck. She let go of the lever, and the crowd broke out in cheers and applause, as if its team had scored a winning goal. Startled, the boy looked down at his new fans. No adolescent defiance or child’s anguish was visible on his face now. Wide-eyed, grinning, he climbed down the ladder like a boy who never in his life had expected to win first prize.

The ground was undulating under Rustin’s feet, the tavern awning about to collapse on his head, the gallows the only fixed thing in sight. He had seen enough.

As he turned to go, a girl began to mount the scaffold. She wore the same clothes as the Guardians, with a bag slung over her shoulder and goggles dangling from her neck.

Found you! was his first thought, and then: She’s going to replace a Guardian. That’s how it works—short shifts. He watched his daughter come out onto the platform. She took her place between the two girls and planted her feet apart. Then, with the same decisiveness he’d seen from the moment she left the house, Selva reached for the noose and draped it over her head.

His stomach dropped as the trapdoor opened beneath him, plunging him into a void of air. No! He must have said it aloud, because the couple under the umbrella turned around: “Shh!” His neck was tingling, his knees barely held him upright.

“Do you want to leave this world?” the Guardian asked.

No! This time a silent cry. He would run to catch her legs before the rope went taut, but she would be just out of reach, her head listing forward in the choke hold of the noose.

“Possibly,” Selva said.

“What do you want to say to your—”

“Listen, Papa,” Selva said before the Guardian could finish. “The other night you asked why I’m angry.”

She was speaking in her debate voice—quick, strong, a little tremulous with effort. He knew that she had carefully prepared what she was going to say, and from his hiding place under the awning, he was listening. He had never listened so closely to anyone.

“As usual, I didn’t think of an answer fast enough. Well, here’s my answer, Papa: because you never believed the world could be better or worse than the one you gave me. And that breaks my heart.”

A rumble of approval from the crowd.

“Oh, this one’s good,” the woman under the umbrella said to the man.

That’s my girl up there, Rustin wanted to tell her. Our pride and joy. It had been a favorite phrase of his, until Pan came along and Annabelle asked him to stop using it, but sometimes he couldn’t help himself, because even Selva with the noose around her neck was exactly that. Those eyes! Their intelligence shone all the way from the gallows. And didn’t she have a point? Even here at the Suicide Spot he couldn’t imagine any life for his daughter other than the one that had always awaited her under the empire.

“The world was worse than you ever knew, Papa. Remember the exams?”

He would never forget them. Every year in May the whole empire came to a stop for three days while 14-year-old Burgher kids sat for their comprehensive exams. In the city by the river the authorities raised banners across buildings and lampposts to proclaim pride in their children and wish them luck. The rituals were ancient, unchanged since Rustin had sat for his. The night before, Annabelle had made the traditional meal of baked rabbit, asparagus, and custard. Rustin drilled Selva one last time on complex equations and imperial history. Pan touched his sister’s forehead with a sprig of rosemary, and the family held hands around the table and solemnly recited the Prayer for Wisdom and Success: “If it cannot be me, then let it not be me. But let it be me.”

The next morning, Burgher parents—oblivious to the fighting that had broken out in the capital—had lined the walkways and cheered as their children filed into schools with pencils and notebooks and tense faces, some bravely managing a smile, others rigid with fear. A few of Rustin’s colleagues were on hand in their professional capacity in case a child fainted. As Selva walked past her parents, she kept her eyes fixed straight ahead. “Look at her,” Rustin whispered to Annabelle. “She’s going to murder it.”

“I had to place in the top 5 percent,” Selva went on from the gallows. “Not just to qualify for provincials and have a shot at the Imperial Medical College. But for you to still love me.”

Someone in the crowd loudly booed.

Selva, no! Not true!

“I didn’t look at you, because I was afraid I’d see it in your eyes. Being your daughter, I did what I had to.”

As always, the results had been announced in the main square two days after the last exam, with practically the entire city in attendance. It was a gorgeous spring day, dry and fragrant, lilac and chestnut trees coming into bloom. One of the old councilors mounted a temporary stage erected in the middle of the square, next to the statue of a historic Burgher that stood on a pedestal surrounded by a gushing granite fountain, and for an hour he read from a long scroll of paper, while the children who had taken the exams lined up at the foot of the stage facing out toward the crowd. When they heard their name called, they stepped forward and shouted, “Here for city and empire!”

The names were read out in order from first rank to last. The family of Selva Rustin did not have long to wait. Out of 179 children, she was third.

“You beat your papa and your grandpa,” Rustin had said that night over the most expensive bottle of wine he owned. “What a day for the Rustins.” On their coat of arms, in the quadrant with the caduceus, next to his own initials he carved SR, welcoming his daughter into the family guild. She was set for life. And as he stood now in the shadow of the gallows, he thought: We sat around the kitchen table and sang our favorite songs. You pretended Zeus was your patient. Was that world so bad?

“The next day, the boy who sat beside me in class wasn’t there,” Selva continued. “We all knew why. He was down around 170.”

Everyone in the square had been keeping a rough count as the councilor approached the bottom of the list. Burghers with no family interest in the results were there just to see who had fallen into the bottom 10 percent—that was a bigger draw than honoring the top 5 percent, who would sit the following month for the provincial round. Even if you lost track of the count, the cutoff point became clear as soon as the shouts of “Here for city and empire!” started to come out weak and choked. A few children didn’t even answer when their names were called.

“Iver was an Excess Burgher.”

Everyone knew what future lay in store for the bottom 10 percent. They, too, were set for life. No prohibition had been announced, but they would never be allowed to join a guild. They would finish the school year and then look for work. The lucky ones would find a job in one of the markets, or learn a trade in the Warehouse District, or, with the right family connections, go to work for the city as a street sweeper or trash collector. Some of the girls were hired as servants in the homes of higher-status Burghers, though Rustin refused on principle to consider it. A few sank into the underworld of prostitution.

But the great majority of Excess Burghers would end up like the ones who drank and fought all night at the Sodden Spot, lay around the main square asleep at midday, and spent most of their foreshortened adulthood in the city prison. Rustin’s next-door neighbor thought they should be sent directly from school to compulsory work gangs. Some disappeared from the city and were swallowed up in the Yeoman hinterland. Most Burghers considered it more respectable, more in the natural order of things, to be a Yeoman than an Excess Burgher.

When Rustin was a boy, there had been no such people as Excess Burghers. Every child in the city was admitted into a guild—of course, some at lower status than others. But around the time he was studying at the Imperial Medical College, he’d heard that children who had not done well on their exams were leaving school and falling out of view. No ordinance was passed that declared the bottom 5 percent of Burgher children (later raised to 10) superfluous, but this was the beginning of a long period of economic contraction throughout the empire, and competition for a dwindling supply of guild positions became intense. That was when the practice began of parents withholding food from children who performed badly on their pre-exams as an incentive to study harder. (Rustin personally thought this was taking things too far, though he kept the opinion to himself.) The first accounts of cheating and payoffs during exam week surfaced—a blow to the belief in fairness on which the whole system of guilds depended. Excess Burghers became a fixture of imperial life, the answer to a chronic social problem, the unfortunate result of simple arithmetic.

“Do you remember what you said that night?” The tremble in Selva’s voice was thickening; she was coming to her purpose. “I told you about Iver, and you said—”

That’s just the way it has to be, Sel. She had come home from school troubled, and he’d wanted to comfort her. He hadn’t wanted poor Iver’s fate to take away from her magnificent achievement. She hadn’t replied, but a cloud had passed over her face.

“That’s just—the way—it has—to be.” Selva raised her chin, causing the length of rope above the noose to go slightly slack. She closed her eyes and shook her head and stamped her foot on the platform just as if she’d reached the end of endurance during one of their arguments that had escalated far beyond his wishes. When she opened her eyes, they pierced his chest. “Why?” she cried. “Why was that just the way it had to be? Why in the world did you ever think that was just the way it had to be?”

More approval from her audience, shouts of “Why? Why?”

“Here’s what you should have said, Papa: ‘I’m sorry, sweetheart, but our whole life is a stinking pile of shit, that’s how it is, we live on it, we eat it, we fuck on it, we’ll be buried in it, but I love you so let’s not talk about it anymore.’ ”

The shouting grew wild. Even the two Guardians were shouting—they had become part of Selva’s audience. Her color rose and her throat quivered inside the noose and her lips tightened in expectation of a response that he wasn’t there to give. He felt as if he were letting her down by not standing beside her on the platform to receive the full force of her indignation, to coax out the last glimmer of her brilliance. One word of his and she’d finish him off, cut him to pieces. He was witnessing one of the greatest moments of her life, as great as that morning in the main square. That’s my girl, he thought again—but also: It wasn’t just me! Everyone believed it. In the old days beggars were drawn and quartered in that square. It sounds terrible now, but four months ago Excess Burghers were normal. You’d be surprised what people can get used to.

“If you’d said that, it would have helped me. But you didn’t have the courage.” Selva dropped her chin and lowered her voice. “So I kept going. I started cramming for provincials. My dream was to reach the imperial round. Instead, we had an Emergency.”

A cheer rose, half-heartedly—they weren’t sure where she was headed.

“That was the end of exams. To be honest, it felt like the end of me. I actually, literally, didn’t know who I was. Without the next round, why get up in the morning?” She gave a hollow laugh. “Then Together came, with the six principles. Suddenly people seemed happier, they started talking louder and laughing, even with strangers. The rules of Good Development came from the empire, from on high, but Together was our own creation. I thought: Okay, I’ll do that. I’ll join a self-org committee—even Iver’s in one. I’ll be the best damn Together girl in the city.”

Someone laughed too loud. Rustin knew from the tremolo in Selva’s voice that things were going wrong.

“Except Together wasn’t about that—it was the opposite of that. ‘I am no better and neither are you’—that’s the second principle!” Selva brought her hands to her forehead and squeezed her eyes shut as if a massive headache had just come on. “So here I am. I don’t have the right thoughts, I keep thinking things I don’t want to think, they go around and around and I can’t make them stop. I can’t stop being your girl!”

The woman punched the air with her umbrella. “Oh my God, she’s great!”

The Guardians spoke to Selva as they’d spoken to the boy, telling her what it would mean to leave the world, reminding her to think of her Better Human, but none of it worked, her silence was too strong for them. She stood there in the grip of unuttered answers that would have defeated their philosophy, and her father knew that she was struggling with the decision. But before she reached it, the Guardian released the lever and the second Guardian embraced Selva. She removed the noose from her own neck and descended the ladder into a swarm of cheers with failure in her eyes.

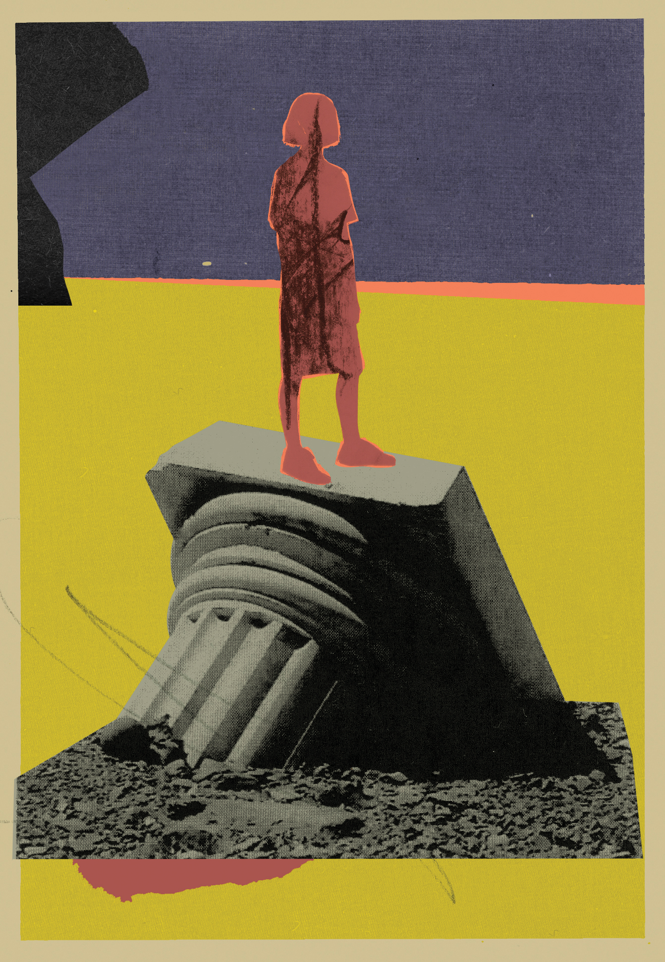

* Lead illustration sources: Mads Perch / Getty; Westend61 / Getty; MirageC / Getty.

This excerpt was adapted from George Packer’s novel The Emergency. It appears in the December 2025 print edition.

The post We Are Not One appeared first on The Atlantic.