Photographs by Caleb Alvarado

On the afternoon of Sunday, August 11, 2024, a few hours after attending church with his wife and three children, Ryan Borgwardt, a 44-year-old carpenter, left home with his kayak, tackle box, and fishing rod and arrived at Big Green Lake, one of the deepest lakes in Wisconsin. The Perseid meteor shower was expected to peak that night, one of the best times of the year to see shooting stars. Stargazers could glimpse dozens an hour, golden streaks that appeared to fall from the constellation Perseus.

At about 10 p.m., Ryan pushed the kayak into the inky-black water. He glided past the water lilies and cattails and headed toward the lake’s deepest part, near its western end. It was so dark, he could barely see beyond the kayak’s nose. Above him, the night sky sparkled.

The Day of the Disappearance

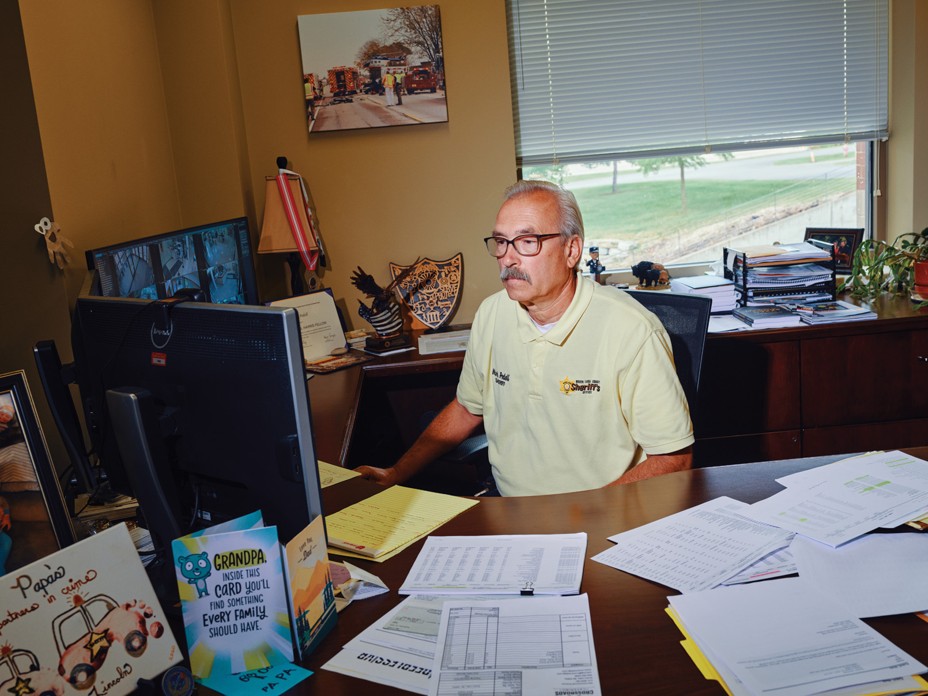

A little after 6 o’clock the next morning, Matthew Vande Kolk, chief deputy of the Green Lake County Sheriff’s Office, kissed his wife and daughter goodbye and stepped out of his Victorian farmhouse.

Vande Kolk, 47, was second in command of the department. Just back from a week’s vacation, he was hoping for a quiet day to catch up on paperwork. As Vande Kolk pulled onto a two-lane road, he alerted dispatchers that he was signing in for duty. Then he drove the roads he’d traveled since he was a boy, across prairies ripening with sweet corn and soybeans, gently sloping fields that met blue sky at the horizon.

Green Lake County’s 19,000 residents are predominantly white, churchgoing, and Republican, many of them farming, or working at gas stations and grocery stores, restaurants and lakeside resorts. To Vande Kolk and the other deputies, Green Lake was a place where people knew their neighbors, compared tractor sizes, and valued common sense above book smarts.

Although murders were rare in the county, deputies handled traffic crashes, child abuse, burglary, fraud—but at a much lower volume than in big cities. They also handled calls more typical of the rural Midwest: trespassing coyote hunters, missing snowmobilers, pickup trucks that had fallen through ice. Deputies knew many of the people they detained. Arrest Frank for a DUI on Monday, and you might find him ringing you up at the Dollar Store register on Thursday.

It wasn’t Mayberry, but it was close. Many of the sheriff’s deputies had grown up in the area, the older among them driving tractors and milking cows. All of them knew how to skin a deer. All of them had chased suspects into cornfields, a reliable way to evade arrest in Green Lake.

As Vande Kolk headed to the office, he heard deputies on the radio talking about a kayaker who’d gone missing on Big Green Lake. A woman had called 911 at 5:24 a.m. to report that her husband had not returned home the previous evening. He’d last texted from the lake, where he’d gone to fish and stargaze.

Around 5:45 a.m., deputies had driven to public boat launches, searching for the family’s minivan, a gray Grand Caravan. In a back lot at Dodge Memorial County Park, a deputy spotted a car fitting that description. He tried the handles—all locked. He peered inside with a flashlight, looking for a note, clothes, anything. He saw a water bottle with Dad written on it. He walked around the car, looking for signs of damage or evidence of a struggle. Everything appeared intact.

Vande Kolk pointed his pickup truck toward the lake, known for a color that could shift from deep forest to nearly jade in different lights. Formed by the retreat of ancient glaciers that left a hole seven miles long and two miles wide, Big Green Lake is 236 feet deep at its cold, dark center. Large muskies, prehistoric-looking fish with canine-style teeth, lurk there. Vande Kolk had spent years on the lake trying to catch one. The shore is lined with multimillion-dollar homes, many of them owned by wealthy out-of-towners who swell the county’s population each summer. About once a year, someone drowns. Because of the depth, bodies are hard to find.

Two deputies were searching the lake in a 21-foot Boston Whaler. Around 6:30 a.m., they pulled alongside a fisherman who said he’d spotted a kayak floating upside down near the middle of the lake. They sped that way, slowing as they caught sight of a kayak, its back half submerged. They flipped it over to see if anyone was trapped beneath. Nothing. One of the deputies marked the exact coordinates. Then they towed the kayak to shore.

Vande Kolk pulled into a parking lot where Sheriff Mark Podoll had recommended they gather. He stepped out of his truck and walked toward the lake glittering in the morning light, a thousand diamonds flickering back at him.

Detective Sergeant Josh Ward sat in his car near the water and called the kayaker’s wife, Emily Borgwardt. She answered quickly, sounding worried.

Emily told the detective that Ryan had left their home in Watertown, about an hour from Big Green Lake, at around 4:45 p.m. the previous afternoon. He’d driven the family minivan to a friend’s house to pick up wood pellets for his stove. Before setting off, he’d mentioned that he might drop the kayak in the water somewhere on his way home, and attached an enclosed trailer with the kayak. He’d told Emily over the weekend that he wanted to fish on Big Green Lake, which would be roughly on his way.

Emily told the detective she’d texted with Ryan the previous evening. She forwarded screenshots of their exchange.

At 10:12 p.m., Emily had written, “Night. Love you.” About 15 minutes later, she’d texted again, telling him that their older son, 17, was spending the night at a friend’s house.

Five minutes later, Ryan texted back: “I may have snuck out on a lake.”

Emily: “That would have been nice to know…I was beginning to wonder why you weren’t home.”

Ryan apologized, but then added: “Temperature is perfect.”

Emily: “Nothing new. I should be used to it by now. So many nights I have no idea where you are when it’s late.”

Ryan: “The meteor shower is awesome in the dark.”

Emily asked Ryan to turn on his location-sharing in the Life360 app, which he did.

Emily: “Again, no communication. Would have been nice to know.”

Ryan: “I’ll work on this communication thing.”

Emily: “It sucks going to bed not having any idea where you are. Just saying.”

Ryan told Emily he’d forgotten his paddle and was instead using a fishing net.

Emily: “No paddle is dumb.”

Ryan: “I love you…goodnight.”

Emily: “Night. Love you too. Be safe.”

Ryan: “I’ll start heading back to shore soon.”

Emily: “K.”

After her last text, at 10:49 p.m., Emily said she fell asleep. When she woke around 5 a.m., Ryan still wasn’t home.

Emily texted him at 5:12 a.m.: “Where are you?????”

Then, at 5:16 a.m.: “Babe?????”

To Sergeant Ward, Emily seemed earnest and cooperative. No, Ryan didn’t have any mental-health issues. She definitely didn’t think he was suicidal. He was an experienced kayaker, as well as a decent swimmer.

Ward asked Emily to send him screenshots from the Life360 app, which showed Ryan heading northwest toward the center of the lake and then moving eastward. After that, the app showed him taking a hard 90-degree turn north. At 11:55 p.m., his trail stopped. Ward wondered if Ryan had had an accident trying to paddle with the fishing net.

Deputies had blocked off part of Dodge Memorial County Park and were asking fishermen to keep an eye out. In the lot, they parked the county’s mobile command center, a large RV with computers and air-conditioning, along with a trailer that carried a search drone and had a big outdoor television on one side. Deputies watched live footage from the drone as it flew across the lake.

Chief Deputy Vande Kolk spent much of the day standing on the bow of the Boston Whaler, looking into the water. It was so clear that he could see at least 10 feet down. Unless Ryan had gotten tangled in the weeds near shore, Vande Kolk felt confident that they’d find him.

The Life360 app, and the location of the minivan and the kayak, had provided clues about where to look. But Ryan might have tried to swim to shore and gotten tired along the way. In the dark, disoriented, he could have headed in any direction.

If Ryan had drowned, his lungs would have filled with water, sinking him to the lake bottom. He’d remain there until his decomposing body built up enough gases to float back to the surface. In aquatic-rescue parlance, this is known as “the pop.” The depth and water temperature determine how long it takes for a body to pop to the surface—anywhere from days to weeks.

Below a certain depth, however, pressure prevents gases from building up, and keeps the body from rising. If Ryan had drowned anyplace deeper than about 100 feet, he might remain in Big Green Lake forever, unless divers or sophisticated sonar equipment were deployed to find him.

As Ward updated Emily throughout the day, he could tell she was struggling to get her mind around the idea that her husband was never coming home again, that she’d be raising three children alone. She was fiercely religious and had begun to say things like “Ryan loved the outdoors. If he had to meet God, that’s the place I would have picked for him.”

At sunset, the sheriff’s deputies called off the search for the night. When Emily asked Ward how long they would continue searching, he sensed she was worried that they would stop too soon, leaving her trapped in a sort of purgatory, trying not to hope but still hoping.

They resumed at daybreak. Around 9:30 a.m., a fisherman called to say that he’d hooked a fishing rod while trolling in about 20 feet of water. It was in the same area where Life360 had shown Ryan’s 90-degree turn north. Sergeant Ward sent a picture of the rod to Emily. She showed it to her younger son, who often fished with his father. He confirmed that it was his dad’s.

Around 2:30 p.m., another fisherman alerted deputies that he’d found a tackle box floating near the Heidel House, a resort on the lake’s northeastern shore. A deputy retrieved it and brought it to the mobile command center. Ward opened the gray box. The stench of rotted catfish bait filled the air. The deputies, obsessive fishermen, leaned in to study the lures, to see what kind of man the tackle box belonged to. His was a random assortment, the stuff of Walmart value packs, including the clip-on bobber balls that amateurs use. They also saw two sets of keys and a brown wallet. Ward removed the wallet, flipped it open, and found a driver’s license. He read the name: Ryan Borgwardt.

Judging by the fact that the kayak was found approximately three-quarters of a mile northeast of Ryan’s last known location, and that the tackle box had shown up farther northeast, about where they would have expected after two days of drifting, the deputies’ best guess was that Ryan had fallen out of the boat, picked the wrong direction to swim, and drowned.

Deputies discussed whether to enter Ryan as a missing person, which would have triggered checks in state and federal databases to see if he’d been in contact with authorities in other jurisdictions. They decided against it; Ryan wasn’t a missing person—he was somewhere in the lake.

Green Lake County Sheriff Mark Podoll believed that the best hope of finding Ryan was Keith Cormican, a search-and-recovery expert who lived a couple of hours away in Black River Falls. He arrived within a few hours, driving a Denali pickup truck hauling his 22-foot search boat. He believed he would quickly find the kayaker, partly because he knew Life360 data to be extremely accurate. He drove to the area of the lake where the last signal had come from and lowered his “towfish”—a four-foot-long, 65-pound device that emits sound waves, which bounce back from the bottom of the lake to create an image the way an ultrasound captures pictures of an unborn baby. Cormican had spent thousands of hours studying sonar images that looked like the desertscapes of Mars, and could quickly discern if a tiny blip was a log or a body.

Cormican and sheriff’s deputies spent that afternoon traveling back and forth across the lake at about four miles an hour, as if mowing a lawn, pulling the towfish on a cable behind them. The sonar produced video of the lake bottom, which Cormican squinted at on a small screen. Every so often, deputies would think they’d seen something significant—a round object that looked like a head—and Cormican would quickly dismiss it as a rock or a beer can. Several times when deputies were especially convinced that they’d found a clue or a body part, Cormican lowered his underwater drone, which retrieved the object with a mechanical claw, confirming his assessment.

Once, in the late afternoon, Cormican pointed out a sonar image that looked like an arm and a leg. Word traveled quickly across the lake that they might have found the kayaker. Cormican lowered his drone, navigating it through the water with a remote control, and moved in for a closer look. It was a forked log.

By the end of the second day, Cormican was puzzled. He’d driven the search area dozens of times. With a lake bottom as clean as Big Green’s, the kayaker’s body should have been easy to find.

Cormican told the sheriff he was expected in Green Bay the next morning, for another water-recovery mission. But he promised he’d come back in a few days. Before they expanded their search area, though, Cormican recommended that the sheriff take another look at the kayaker’s history. “Just make sure he’s not drinking margaritas on a beach somewhere,” Cormican said.

Five Days After the Disappearance

On Saturday, Sergeant Ward went to meet Ryan’s wife and children at their one-story ranch house on an acre of land in Watertown. Emily greeted him with a warm smile. She introduced Ward to her parents and children, who sat on a couch and chairs in the living room.

Detectives had already scoured the couple’s social media, trying to get a sense of who the Borgwardt family was. Emily taught first grade at a Lutheran school. On Facebook, she’d shared a recipe for coleslaw orzo salad with toasted almonds and dried cranberries, displaying a photo of how she’d packed it in Tupperware for the coming week. She posted about baking homemade chocolate-chip scones, gardening, laundry. “Whoever invented the delay time feature on my washing machine is my favorite person this busy week! Set the timer now and my laundry will be ready for the dryer when I wake up!”

Emily, who was 44, described Ryan, her husband of 22 years, as a family man, a devoted father. He was a volunteer firefighter who served as an usher at their Lutheran church. He owned a woodworking shop, where he built custom cabinets and furniture. He did not drink much. Emily said Ryan rarely had time to himself and had probably been craving some solitude on the lake.

Ward asked if the family had any financial issues. Emily said Ryan did seem stressed about money at times and complained about not making as much as he’d like. She said he’d recently accumulated some credit-card debt, the details of which she did not fully know.

Ward asked the family about Ryan going out onto the lake so late without a paddle—did that strike them as odd? Not at all, the family said. Emily’s father said he believed Ryan had attention deficit disorder; his son-in-law often lost track of things and started projects that he didn’t finish. Emily’s father didn’t say it in a disparaging way—more like That was just Ryan.

Ward asked to speak with Emily alone so he could inquire about their marriage. Emily said their relationship was strong. She had a few gripes—Ryan was not good at communicating, nor was he good at gauging how long a task would take to complete. Ward asked if he’d had any recent health issues or medical procedures. Emily mentioned that he’d gone to the hospital six or seven weeks earlier for a reverse vasectomy. She said he’d ended up being “part of that 2 percent” who had pain after the original procedure. Ward asked Emily if he could look at Ryan’s laptop, and she readily provided it. He pulled up Ryan’s browser history—nothing unusual.

Ward came away with the sense that the Borgwardts were solid, decent people. The time he spent with them had strengthened his determination to keep searching, because they deserved a proper goodbye.

Six to 52 Days

Cormican kept expanding his search area. It was tedious work, lowering the towfish into the water, driving slowly, returning home at dark with nothing. He got tired of Big Green Lake. Every time he left town, he hoped not to return. Then Sheriff Podoll would call and tell him how nice the Borgwardt family was and how Cormican was their only chance for closure. And he would climb back into his truck and return to the lake that did not seem to want to give up its dead kayaker.

At the sheriff’s office, Sergeant Ward had hung a color-coded map of the lake on a wall. He’d highlighted in orange any areas that were less than about 80 feet deep. If the kayaker had drowned in those spots, he already would have surfaced. The deeper parts of the lake, highlighted in pink, were what Cormican called the “hot zone.” Day after day, Ward and Cormican went out onto those parts of the lake, crisscrossing them to capture images from multiple angles.

Cormican didn’t find everyone he searched for, but he found most of them. He’d recovered his first body in the 1990s, after two men who’d been drinking tried to swim across a Wisconsin pond. One disappeared along the way. Cormican, then in his 30s, put on a wetsuit and a scuba mask and tethered himself to his older brother, Bruce, a volunteer firefighter in Black River Falls. Groping through the muck with his hands, he found the body in about 10 feet of water. It was terrifying, but also gratifying to bring closure to the family.

To find the bodies of those who drown in Wisconsin’s more than 15,000 lakes, searchers used to drag large grappling hooks across lake beds, but this technique disfigured corpses. The gruesomeness bothered the Cormican brothers, so they assembled a volunteer dive team and worked to devise better methods.

In 1995, an emergency page went out in Black River Falls. A father had drowned while canoeing in Robinson Creek with his daughters. On the third day of their search, as Bruce waded into the water holding a safety line, feeling for the man with his feet, swirling currents swept him away. When rescuers were able to reach Bruce, he’d been too long without air. By the time they got him to the hospital, he was beyond saving; they took him off life support the next day. He was 40, with a wife and two children. Keith Cormican drew some consolation from not having to leave Bruce’s body in the cold river, unclaimed. The experience deepened his commitment to his work; he now understood viscerally that the ritualized ways we say goodbye are essential for processing grief.

Cormican closed his landscaping business, invested in cutting-edge sonar equipment, and bought a boat. In the years since, he’s become one of the world’s most sought-after water-retrieval experts, pulling the dead out of lakes and rivers from Romania to Panama to Nepal.

After searching Big Green Lake for so many days, Cormican was asking himself, Why can’t I find this guy? Am I losing my touch? He’d wake at 3 a.m. and click through sonar images on his computer, zooming in on every speck.

What haunted Cormican most about finding drowned bodies was the faces—eyes opened unnaturally wide, mouths frozen with what Cormican could only describe as the fear of God. But for him, the one thing worse than finding drowned bodies was not finding them.

53 Days

On Friday, October 4, 2024, Chief Deputy Vande Kolk was steering the boat while Cormican monitored the equipment. The leaves were turning. Before long, the lake would freeze.

The whole town seemed weary of the search. Many residents were beginning to think the body would never be found. He’s not in the lake, the retired guys who gathered at the local coffee shop each morning kept saying. Sheriff’s deputies, feeling defensive about the time and money they were spending, would tell people that the family needed closure. “We’re going to keep looking,” they said.

Navigating along the surface, Vande Kolk maintained a consistent speed as the boat moved north to south in a grid pattern. The towfish needed to stay 15 to 20 feet from the bottom to capture good images. Drive too fast, and the towfish would rise too high. Too slow, and it might hit the bottom. Any miscalculation would leave gaps in their search grid and potentially damage a $60,000 piece of equipment.

Later that day, the men returned to shore. Cormican had spent 20 days on the lake. “I’ve searched this lake like I’ve never searched another body of water,” Cormican told the sheriff. “You’ve got to start looking elsewhere.”

56 Days

The following Monday morning, Sheriff Podoll declared that it was time to investigate new angles. Detective Jeremiah Hanson reached out to the Mid-States Organized Crime Information Center, a group of nine states that shared law-enforcement data, and asked for a historical record of every time someone had searched Ryan’s name—during a traffic stop, for example. If Ryan had been involved in criminal activity in another town, the report should reveal that. When Hanson received it, he sent a copy to Sergeant Ward.

Ward saw some recent entries that made sense—a number of searches after Emily, Ryan’s wife, had called 911. But an additional entry caught his eye: Canadian authorities had searched Ryan’s name at the Detroit-Windsor Tunnel, an underwater highway that connected Detroit to Windsor, Ontario, at 12:30 a.m. on August 13, 2024—the day after he’d disappeared. That was odd. Ward talked with a U.S. official at the border, asking him if he knew why the Canadian authorities had run Ryan’s name on that date. The official said he’d look into it. Ward hung up and sat in silence for a few moments.

He and Hanson walked down to meet Podoll and Vande Kolk in the chief deputy’s office. “You guys are going to want to sit down,” Ward said. Then he told them that Canadian officials had searched Ryan’s name on August 13.

“What?” the sheriff said.

“His name was run at the Canadian border the day after he disappeared,” Ward said. He watched his colleagues absorb what that meant.

“Well, holy shit,” the sheriff said.

Vande Kolk slammed his fist on the desk. “Motherfucker!”

They’d spent almost two months searching the lake.

Vande Kolk took this the hardest: Weeks earlier, he’d told Ward not to enter Ryan as a missing person, which might have triggered the search earlier. He started cursing so loudly that the sheriff had to tell him to calm down.

Still, all they knew was that someone in Windsor had searched Ryan’s name shortly after he’d disappeared. Maybe a police officer there had simply been curious about the case and looked him up. Or maybe someone had stolen Ryan’s identity.

Vande Kolk contacted an agent with ICE, who told him that Ryan had obtained a passport in 2017. Ward texted Emily and asked if she knew where her husband’s passport was. A couple of minutes later, she texted Ward a picture of it. It had the same number as the one Ryan had been issued in 2017.

Then ICE told Vande Kolk something new: Ryan had reported his passport as lost or stolen around April 30, 2024—about four months before he’d disappeared. A replacement passport was issued on May 22, 2024. That was the passport that had been run at the Canadian border.

Detective Hanson kept calling an official who worked at the border, hoping to learn if it was actually Ryan who’d crossed there, not someone else. “Dude, please,” Hanson implored, pleading for any information. The official apologized, explaining that he wasn’t authorized to say anything.

“But if I were you,” the official told him before hanging up, “I’d stop looking in the lake.”

58 Days

On October 9, 2024, Podoll and Ward met with Emily. The officers still didn’t know exactly what had happened, but they were growing more convinced that Ryan had duped them, and they found it hard to believe that he could have pulled this off alone. Had Emily been in on it?

Around 11:30 a.m., as the men took a seat at Emily’s dining-room table, they noticed a painting hanging on the wall, which appeared to be an image of Jesus and Ryan, holding hands as they walked away together along the water. You have got to be kidding me, the sheriff thought.

“We’ve got some information we’re going to share with you,” Podoll told Emily. “It’s very important that this information stays right here at this table.”

Emily nodded.

“We’re changing the direction of our investigation,” he said.

“What?” Emily asked.

“We don’t believe Ryan is in our lake,” he said.

Emily looked confused. “What?” she asked again.

“We believe Ryan is still alive.”

The men studied Emily as she absorbed this information. Her face turned so pale, they worried she would pass out.

Warning her that what he was about to say might be hard to hear, the sheriff told her that they believed it possible that Ryan had faked his own death and abandoned his family.

He felt as if he could read Emily’s feelings as they passed across her face: relief, then confusion, then anger, then doubt. Tears slid down her cheeks.

“I don’t know what’s worse—him dying, or knowing that he’s alive,” she said. Ward and Podoll had the same thought: She’s not faking this.

“What about our kids? How could he do that to them?” she asked. “Was my marriage really that broken, and I didn’t know?” Her disbelief seemed to be growing. “Ryan would not do that to us.”

Podoll told Emily what they’d learned about the passports and the Canadian border, but acknowledged that they did not know where her husband had gone or if he was actually still alive.

“This is what I need you to do,” he said. “You cannot say anything to anyone.” They didn’t want to suggest publicly that Ryan had deceived everyone until they knew for certain. And a media circus would make their investigation more difficult.

“I will do whatever you need,” Emily said. The sheriff worried that, in asking her to carry this secret alone, he was imposing an impossible burden.

“What about the church?” she asked as the officers prepared to leave. “What about all the people who prayed for him?”

About an hour later, Emily sat in the auditorium of her older son’s high school for the annual talent show. A piano melody filled the room as her son stood onstage beneath a spotlight, holding a microphone and singing a duet with another student.

Emily had driven to the school in a fog. She’d considered not going, but her son was expecting her, and how would she explain not being there? She’d taken a seat in the auditorium, struggling to mask her emotions behind a cheerful-mom look. After the teens hit the first verse of the chorus—“Ain’t no mountain high enough!”—the crowd began to clap to the beat. Emily felt sick.

She had grown up in Lutheran schools. She spent her days teaching first graders. Raise your hand, be polite, Jesus loves you. She lived in a concrete, simple world where Tuesday follows Monday and two plus two equals four.

She thought back to the morning she’d learned that Ryan had disappeared. She’d been awakened by their puppy, and had been annoyed at Ryan, who hadn’t gotten up early with the dog like he was supposed to.

She thought about the look on the face of her older son as he arrived home early from a sleepover that morning, having been told there was a family emergency, to find a patrol car in the driveway. The teenager was crying, hugging his sweatshirt to his face. Mom, what’s going on? he’d asked. Buddy, your dad is missing, she’d told him. Family and friends had crowded into the house as they waited for information. By nightfall, Emily had accepted that Ryan had drowned in the lake. A devout Christian, she believed that Ryan’s death must have been part of God’s plan, and that he was now in heaven.

As the search stretched on for days, then weeks, Emily had kept her cellphone near, waiting for news about Ryan’s body. Along with managing her own grief and that of her children, she was taking on the tasks her husband used to do: paying the bills, making sure the garbage cans got to the curb. Every time she felt overwhelmed, people showed up to help. A retired police deputy mowed her lawn every week. Several dozen volunteer firefighters from the station where Ryan had worked came over to trim trees and stack wood. How was she going to explain to them that she was not a grieving widow but … what? A spurned wife? A dupe?

That night, after the talent show and dinner and homework, Emily lay awake in bed, unable to sleep. The peace she’d felt, surrendering herself to God’s plan, had been replaced with a cold unease. She struggled to believe that Ryan would have willingly abandoned the family. Had he gotten himself into trouble, something sinister on the dark web? Maybe, she thought, he’d sacrificed himself to protect her and the children.

Whatever had happened, Emily knew she could no longer attribute it to God’s plan. This had been her husband’s choice, the actions of a mortal man, one locked in what she could only assume was a terrible battle with temptation and sin.

At the sheriff’s office, Detective Hanson opened Ryan’s laptop, which Emily had given them. Hanson, the department’s digital-forensics expert, quickly found evidence suggesting that Ryan had deleted his browser history the day before he disappeared. Huge red flag. He sent the laptop to a state lab.

Poring through gigabytes of data on the hard drive, an investigator at the lab found a document labeled “bank questions.” The first question read: “From the US to my new bank account in Georgia. What is the most common way people do this?”

Another document appeared to detail Ryan’s exit plan. He had listed the number for a burner phone as well as old and new email accounts. He’d switched to a new account with Proton Mail, an encrypted service based in Switzerland, a smart move for anyone trying to elude detection abroad: Executing search warrants on Proton is much harder than on U.S.-based services such as Yahoo.

Hanson prepared search warrants for each email address, phone number, and credit-card number he found on the laptop. Among Hanson’s discoveries was a Robinhood trading account, which allowed Ryan to buy and sell cryptocurrency. Hanson learned that Ryan had been flagged by the platform for regularly sending funds to a Russian cryptocurrency exchange—about $20,000 between March and May 2024.

Hanson also received a copy of the lost-passport form Ryan had filed in April, on which he claimed that he’d probably lost his during a basement cleanup. Making false statements on a passport application is a felony punishable by significant prison time. So is insurance fraud—and Hanson discovered that on January 16, 2024, Ryan had applied for a $375,000 life-insurance policy. It sure looked like Ryan had taken out the policy while planning to fake his death.

When further digital sleuthing revealed that Ryan had flown from Canada to France on the night of August 13, Hanson contacted an FBI agent assigned to the U.S. embassy in France, who was able to confirm that Ryan had landed in Paris, but did not know where he’d gone from there.

Back when everyone assumed that Ryan was still at the bottom of the lake, Emily’s mother, going through his computer to help her daughter pay bills, had discovered about $80,000 in credit-card debt that Emily didn’t know about. She, along with Ryan’s mother and stepfather, had decided to secretly pay off the debt and not tell Emily. Ryan also owed money to his mother and stepfather.

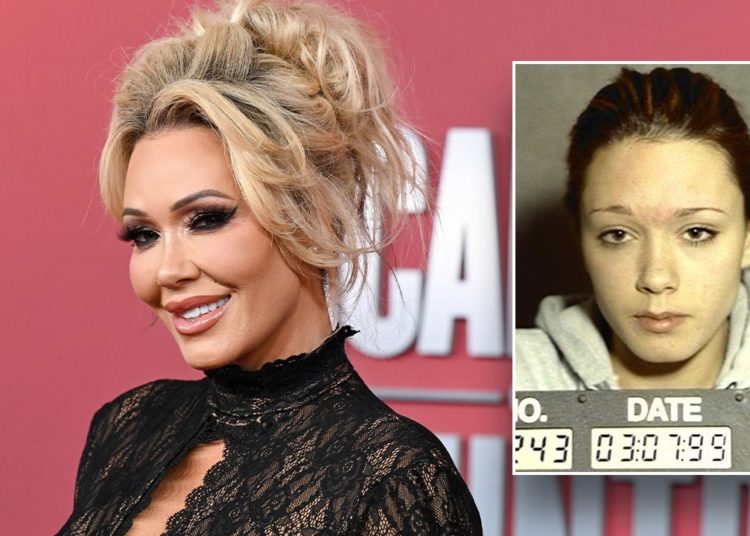

But perhaps the most notable discovery, this one made by the state investigator Hanson was working with, was this: In the spring of 2024, a few months before he disappeared, Ryan had been exchanging messages online with a woman named Ekaterina Vladislavovna, who went by Katya.

In one message, she’d said: “Good luck. I kiss you very hard.”

In another, she’d said: “I just want to be with you!!!”

“Katya,” Ryan responded,“I promise to you that I will love you for the rest of my life. I want no one else. I want to share a life with only you.”

80 Days

For three weeks, Emily kept quiet about what her husband had done, though the tale seemed to grow more sordid every time the sheriff called—she had learned about the woman abroad and deduced the real reason for the reverse vasectomy, a procedure Emily had driven him to. As she struggled to absorb these terrible truths, not being allowed to tell anyone made her feel lonelier than she ever had.

The last week of October had been particularly hard. School and community fundraisers had raised more than $6,000 for the search for Ryan. Emily asked Sheriff Podoll what she should do about the donations. “Don’t say anything,” he told her. “Just go with it.” Emily told him she needed someone to talk to.

Later that week, on Thursday, October 31, Podoll sat with Emily for 90 minutes at her church, explaining to two pastors what was really going on with the investigation. One of the pastors, who had prayed from the pulpit for Ryan, looked confused, a Bible in front of him on the table. The sheriff told them they couldn’t tell their congregants. “I’m not telling you to lie,” the sheriff said. “You just can’t say anything.”

How could he do this to our children? Emily wanted to know. How could he have treated me the way he did on those last days—helping around the house, watching a movie together?

“Okay, I’m going to tell you why he did that,” Podoll said. “He wanted to get out of a divorce. He wanted you to remember him how he was on those last days, so you would have good memories of him. Then he was going to move on with his life.

“In my book, he’s a piece of shit,” the sheriff continued. “I apologize,” he said, turning to the pastors, “but he is.”

88 to 91 Days

In early November, Podoll felt it was time to start revealing what they’d learned more widely. He invited Emily’s and Ryan’s families to the sheriff’s office on Friday, November 8, where he planned to tell them that Ryan was not, in fact, dead. Then he’d hold a press conference to tell reporters.

Early that afternoon, the officers walked into a conference room where about a dozen relatives—including Ryan’s mother, stepfather, father, and three siblings, plus Emily’s mother and father—sat in chairs in a semicircle. Podoll looked around the room and said: “We’re going to talk about a lot of stuff today, and it’s going to be pretty shocking.” He told the group that Emily already knew what they were about to hear.

The case, he told them, had taken an unexpected turn. “We don’t feel that Ryan is in our lake,” the sheriff said. “We believe he is still alive.”

Absolute silence. Podoll had never seen so much disbelief on so many faces at once. After about 20 seconds, the silence broke. Emily’s father sobbed. Her mother dropped her head and wept. Ryan’s brother looked at his wife (Oh my God ) and she stared back (Oh my God ). Ryan’s mother looked relieved but confused. Ryan’s father said, “This is not Ryan—not the Ryan we knew.” Ryan’s stepfather sat quietly, appearing shocked and betrayed. The emotion in the room was so palpable that it threatened to infect the sheriff’s deputies. Vande Kolk clenched his teeth to avoid crying.

Podoll had also invited Keith Cormican to the meeting. Any thought he might have given to the time he’d wasted on the lake was overwhelmed by the sound of the family’s sobs. He’d made all kinds of gruesome discoveries on lake bottoms. But of all the terrible scenes he’d witnessed, he later told me, this was among the worst.

As the meeting was ending, Vande Kolk’s cellphone vibrated. He looked down and saw a string of Russian letters. Holy crap, he thought.

Earlier that day, as the meeting with the family approached, Vande Kolk had suggested to his colleagues that they blitz every phone number and email address they’d discovered in an attempt to reach Ryan directly. The sheriff agreed.

After striking out with a few phone numbers, they turned to email, sending notes to Ryan’s addresses, and also one to his mistress, Katya, giving it the subject heading “Call us.” They attached a photo of Ryan, one of Katya with two young children, and one of Hanson’s badge, to emphasize their legitimacy. “It is very important,” Vande Kolk wrote. “This is the police in Wisconsin USA.” He had sent the email at 9:16 a.m. When he hadn’t gotten a response within a few hours, he sent another one.

Realizing this was likely Katya’s response, he now stepped out of the room and read the email in translation: “Hello. I do not know who you are and why you contacted me. I know the man in the photograph. His name is Ryan. Over the last year he became my good friend.”

Vande Kolk wrote back that he had something extremely important to discuss and could he please have her number.

“Please forgive me, but I do not give out my number to strangers, especially from another country,” she replied. “Please explain, what happened?”

“When is the last time you spoke with Ryan?” Vande Kolk wrote back. No response. About an hour later, he sent another email, with the subject line “Urgent.” Still no response, so he sent a few more emails, including a link to the sheriff’s-office website and a news clip about the case.

At 1:46 a.m. central time, the woman finally responded, and in an email exchange explained that she was struggling to trust an American detective because of the tensions between Russia and the United States. Vande Kolk said he understood, but needed to confirm that Ryan Borgwardt was alive. He asked for a photograph.

The woman wanted assurance that the authorities would not cause her any problems. As far as she knew, she said, neither she nor Ryan had broken any laws.

“Our primary concerns are not whether there were any crimes committed, but to provide some answers to Ryan’s 3 beautiful, amazing children,” Vande Kolk wrote. “Help us give his children peace. Is Ryan with you now?”

Vande Kolk worried that Ryan had been catfished, lured overseas by someone pretending to be a beautiful woman only to find himself kidnapped and ransomed or killed.

Soon the woman told him that Ryan was trying to email but his messages weren’t getting through. Ryan (or someone purporting to be him) and Vande Kolk began sending messages to each other through Katya.

Hoping to verify his identity, Vande Kolk asked a question to which he thought only Ryan would know the answer: the make, model, year, and mileage of the vehicle he’d left at Big Green Lake. The response: “2015 Dodge Grand Caravan. I honestly dont remember the last mileage reading. Maybe 90k. There is no loan on the van. I was pulling a trailer full of wood pellets for my stove. I just picked them up at my friend Adam’s house.”

Definitely Ryan, Vande Kolk thought. He asked him to join a videochat, but Ryan declined. “The truth is I’m terribly afraid to do anything that would help give up my location any more than you or the FBI already know.”

“Please tell me what my future looks like,” he added. “Am I looking at jail time?”

“There are consequences for what has occurred,” Vande Kolk wrote. “Those consequences can be significantly mitigated by your actions going forward.”

Ryan responded by saying he was attaching a video to prove that he was not in danger. It showed him in a bland-looking apartment. “Good evening. It’s Ryan Borgwardt,” he said quietly into the camera. “Today is November 11. It’s approximately 10 a.m. by you guys. I’m in my apartment. I am safe, secure, no problem.”

Vande Kolk and the detectives watched the video a few times. Ryan looked healthy and surprisingly calm. Wherever he was, he seemed to be there by choice.

Faking one’s death is not technically illegal. But the detectives thought there was evidence to support a charge for obstructing an officer—a Class A misdemeanor punishable by up to nine months in jail—because Ryan had planted physical evidence meant to mislead them. Maybe further investigation could lead to more serious charges, such as passport or insurance fraud, but they didn’t know if the feds would get excited about investigating an otherwise-law-abiding husband in the throes of a midlife crisis. Furthermore, the detectives suspected that Ryan was in a country that didn’t have an extradition treaty with the U.S.

For the deputies, the case had become personal. This guy had fooled them. The idea that he might get to disappear without consequence galled them. If nothing else, he needed to reimburse taxpayers for the more than $35,000 they’d spent on the search. So the detectives wanted Ryan in handcuffs. They also wanted him to own up to what he’d done to his wife and children, and to try to make things right with them.

But to bring Ryan to justice, the detectives had to prove that he had planted evidence to mislead them—and they needed him to return to Green Lake.

91 to 112 Days

Vande Kolk set about trying to figure out why Ryan had gone to such lengths to disappear, and what might get him to come back.

An early possibility revealed itself in an email exchange Vande Kolk had with Ryan about his family. “They are amazing people,” Vande Kolk wrote of Ryan’s wife and children. “That’s because Jesus fills their hearts with love, confidence and hope,” Ryan replied. “Their mom did a great job of that with those 3.”

“I agree with you,” Vande Kolk replied. “I have never seen such love and forgiveness in a group of people, and love like that only comes from Jesus.”

The men settled into near-daily communication. Ryan came across as remorseful and polite. He said he really did want to “fix everything possible that I just destroyed about 3 months ago.” He apologized for the time the sheriff’s office had wasted searching the lake.

Soon, though, another side of Ryan emerged. He told Vande Kolk he was angry that the sheriff’s office had made him sound like a “200% dirt bag” in the press conference. He was irritated by the implication that he’d been “living ‘large’” abroad. “That couldn’t be further from the truth,” he wrote. “I truly tried to take as little as possible with me to LEAVE MY FAMILY WITH AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE.” Yes, he conceded, he’d moved a “decent amount” of money over before he left, but he said that he’d given it away to people who needed it more than he did, and that now he couldn’t even afford a plane ticket home.

Vande Kolk pressed him for information about what he’d done. “If all the people that worked on my case in multiple agencies still don’t know how I got to Canada yet,” Ryan responded, “I’m not sure I want to say how I did this.” But Vande Kolk thought he could sense that Ryan wanted to tell his story. This presented another angle of approach. If you need money for a plane ticket, he told Ryan, you could probably get it from a book or movie deal.

“Yes, I think it’s possible the story could make for a decent book or movie,” Ryan replied. He said he might consider it to pay off his debts.

Over time, the email conversation had become familiar, even chummy. Vande Kolk could empathize with Ryan’s urge to escape his life. He thought about all the hours he himself spent on the lake, away from his family, trying to land a musky large enough to be considered “trophy size.”

Still, he found himself becoming disgusted. He’d been married for 25 years to his high-school sweetheart, and they had two children: a son, and a daughter who’d been born with a rare genetic mutation that caused mental and physical delays. They’d stuck it out through some tough things. How could a man just abandon his family like that? Vande Kolk thought. We’ve messed around with this guy long enough.

Dropping his friendly tone, Vande Kolk wrote that he’d heard Ryan’s own father had left the family when Ryan was young. “I cannot understand how you would want to do something like that to your kids,” Vande Kolk wrote. Was Ryan really just going to hide from his children? What he was doing to them, Vande Kolk wrote, was worse than a divorce. “You move off to live a new life, and your kids get no support from you financially, mentally or spiritually.”

Ryan said he’d had no choice. “I just couldn’t handle life anymore,” Ryan wrote. He said he was roughly $200,000 in debt, not including his mortgage, and didn’t know how he would begin to pay that off.

“My life in the Watertown area is over,” he wrote. No one would ever forget what he’d done, even if they ultimately forgave him. “Everything is just so much easier if I’m dead.”

Vande Kolk questioned Ryan’s faith, suggesting that he was making Christians look bad. “You always talk about how you have this need to help others,” he wrote. But “maybe all you care about is yourself.” Ryan’s daughter had recently gotten into a fight with some kids at school. Ryan’s younger son had cried that morning because he didn’t understand why his dad wouldn’t come home. “These kids did nothing to deserve all this. Come back and make it right before it gets worse.”

A day passed with no response. Worried that he’d been too harsh, Vande Kolk sent several recent pictures of Ryan’s kids.

“You can fix this,” he wrote. “Show them what a man of God does when times get tough. Show them what bravery is. Show them your love.”

Coming back would be a terrible idea, Ryan responded. He had nowhere to live, no car, no job, no church. He didn’t want to force his kids to visit every other weekend. “I was that kid, that life sucks,” he wrote. Soon enough, the kids wouldn’t want to spend time with him anyway. “It’s how divorce works,” he wrote. “I will become the enemy.”

But what most concerned him, he said, was being separated from Katya, the woman who had saved him from his loneliness. Without her, “I might as well come home in a box.”

Vande Kolk’s response was blunt: If Ryan could figure out how to disappear to the other side of the world, he could figure out how to return to Wisconsin. Ryan’s parents had each offered him a room to stay in; his mother even said she would welcome Katya.

“For goodness sake Ryan,” Vande Kolk wrote. “Your kids.”

A few days later, Ryan emailed to say that he could come home for up to three months to “fix” as much as possible, but that ultimately he planned to stay with Katya. He said his was a “semi normal American divorce story”—though that semi was doing a lot of work.

He finally told Vande Kolk where he was: Batumi, a city in Georgia, the former Soviet republic. He liked it there, and had gotten to know many Russians, who were “seriously just like us from Wisconsin.”

Vande Kolk kept the conversation light and continued to engage, not wanting to scare off his quarry.

A few days after Thanksgiving, Ryan forwarded a screenshot of his flight confirmation. “Whatever happens now is in God’s hands,” he wrote.

120 Days

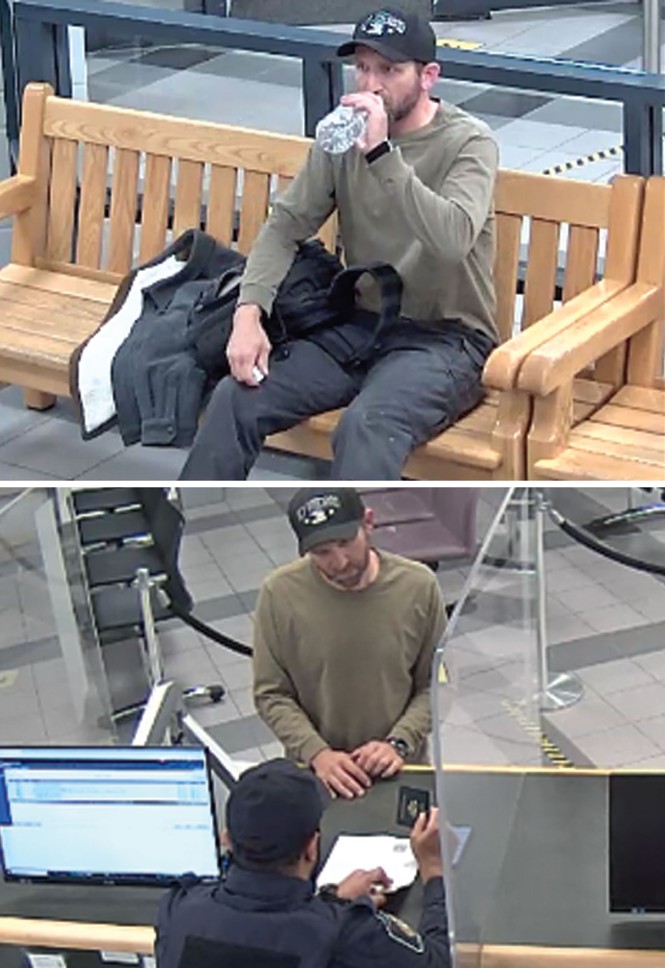

On December 10, 2024, Vande Kolk and Detective Hanson met at the Green Lake County Sheriff’s Office at 5:30 a.m. to begin the roughly three-hour drive to Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, where Ryan was scheduled to arrive at 10:10 a.m. They were nervous. Although the Green Lake detectives believed they had a strong case for an obstruction charge, that was only a misdemeanor—not serious enough to merit an arrest in another state. So they were going to have to persuade Ryan to come to the sheriff’s office and give a statement voluntarily. If he declined to talk, or decided to leave O’Hare on his own, they couldn’t stop him.

After Ryan’s plane landed, U.S. Customs and Border Protection escorted Vande Kolk and Hanson to the secure customs area. As a group of passengers moved toward passport control, Vande Kolk spotted a man wearing a hooded sweatshirt. It’s him. Vande Kolk wondered if anyone else would recognize Ryan from all the news coverage. No one seemed to.

An agent brought Ryan over. “Welcome home,” Vande Kolk said.

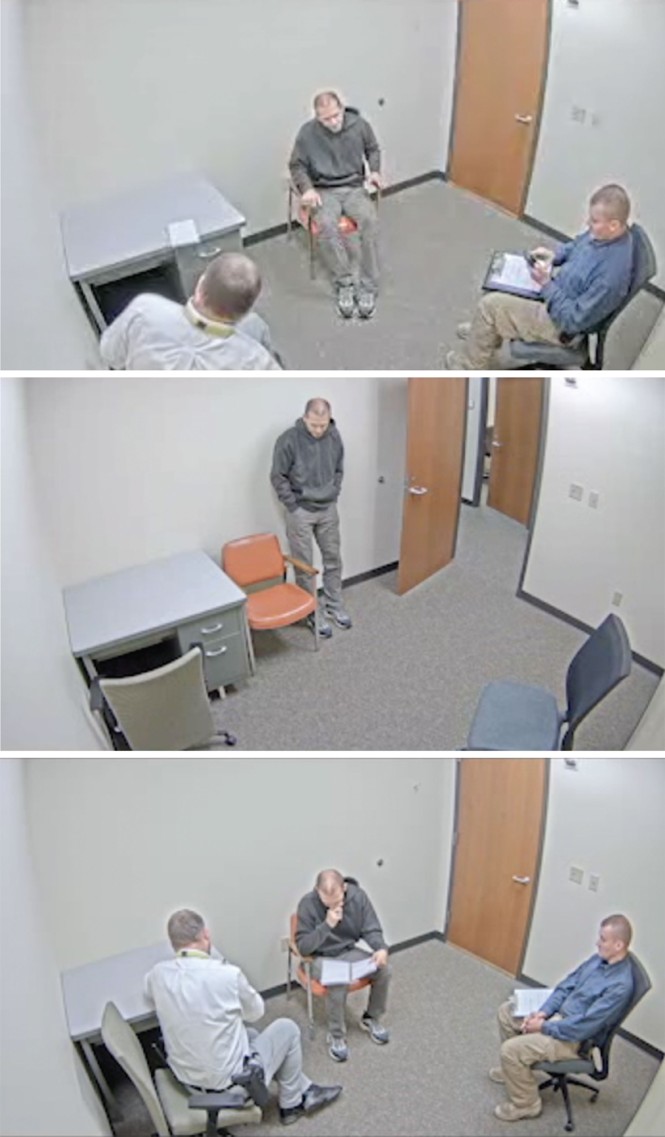

A few hours later, Ryan was sitting in an interview room. Vande Kolk was at a metal desk to Ryan’s right. Hanson sat in another chair and read aloud the Miranda warning.

During the email back-and-forth with Vande Kolk, Ryan had begun to outline how he’d carried out his plot. Now, over three hours in the sheriff’s office, Ryan elaborated.

He first crossed paths with Katya online in December 2023, eight months before his disappearance. “A dating website?” Hanson asked. “Online,” Ryan said, declining to specify further. They’d talked once or twice, and he’d promised to contact her again after the holidays. They reconnected in late January 2024 and quickly became good friends, Ryan said.

By February, the friendship had turned romantic. She sent him video messages in Russian, which he translated to English. They began talking about a future together.

At first the notion of faking his death was purely a fantasy, but soon it began to gel into an actual plan. He researched stories of people who’d ostensibly done it, including a German billionaire who’d vanished while skiing. He considered staging his death while duck hunting on the Mississippi River, because people died there all the time, their bodies washing away. But he couldn’t figure out how to plan a solo trip that far away without making Emily suspicious. He settled on Big Green Lake, because it had areas deep enough for his body to plausibly never surface.

He ordered an electric bike and two bike batteries for about $1,000 on Amazon, then deleted the account he’d used for the purchase.

By now he was committed to the plan. In the week beforehand, he watched the weather, eventually settling on Sunday. That morning, he went to church with his family, hoping they’d have Communion together one last time. But he got asked to usher, which was disappointing, he said, because he didn’t get to sit beside Emily. After church, he went to his shop. One of the things he worked on, he said, was preparing a new laptop for Emily. He explained that he didn’t feel confident in his ability to wipe his own laptop, so he’d purchased a replica with a new hard drive for her. He tried to move over financial records and other files to make things easier for her when he was “dead,” but apparently he’d copied over “one too many things” and left evidence for investigators. He returned home for a couple of hours, hooked up the trailer, and said goodbye to Emily and the kids. He drove back to the shop, where he pulled the trailer close to the building so security cameras would not record him loading the bike. At a Walmart in Oshkosh he bought a duffel bag, snacks, and a ball cap to conceal his face.

He arrived at Big Green Lake around 10 p.m. He parked the van about 10 steps from the water. He stashed the bike and two bags in high grass among trees. Then he loaded his fishing pole, fishing net, tackle box, and a large duffel bag into the kayak. As he glided into the night, he saw campfires dotting the shoreline.

A tailwind helped carry him toward the lake’s center. He’d studied maps of the lake and reached what he believed to be a deep area. One boat passed by, then another. When all seemed clear, he tossed his phone into the water. He used a manual pump to inflate a child-size raft he’d purchased for about $20, and climbed into it. Steadying himself in the tiny vessel, he flipped the kayak, which drifted out of sight. Around midnight, he began paddling. He said he didn’t know how long it took to get back to shore, fighting the wind and the waves with the raft’s toy paddles, but he thought at least an hour or two.

When he got close to shore, he hopped out of the raft. His first step found solid ground. On his second, he sank into black mud up to his waist. He traveled about 40 feet with the muck trying to swallow him. When he emerged from the water, he ran across the road, deflated the raft, and packed it into one of his bags. Looking at the road, he saw that he’d left muddy footprints. “I thought, There’s no way in the world you guys are going to miss these,” he said. He tried to pour water on them but soon realized it wasn’t much use, and he was in a hurry.

Sometime around 1 or 2 a.m., he climbed onto the bike. He rode through the night, pedaling roughly 70 miles, mostly on back roads, all the way to Madison. He stopped a couple of times, to change into dry pants and eat a granola bar. The sky, he thought, had never looked more beautiful.

Around 5 a.m., he said, he’d thought about Emily, because he knew she’d soon be waking and would wonder where he was. Around 9:15 a.m., he stopped in a densely wooded park, where he left the bike. He tossed his damp sweatshirt and the raft in a garbage can. Then he walked 40 minutes to a Greyhound station. He got there just in time for a 10:05 a.m. bus to Toronto, via Milwaukee, Chicago, and Detroit, switching buses twice along the way.

“I’m on the bus,” he said he texted Katya from a burner phone. “So far so good.” Shortly after he boarded, the phone stopped working.

At the Canadian border, agents were suspicious because he had no driver’s license and his phone wasn’t working. But after about 20 tense minutes, they let him through. He arrived at the Toronto airport, where he used his laptop and a prepaid debit card to buy a plane ticket to Europe. He was carrying $5,500 in cash, below the threshold requiring a customs declaration.

The Air France meal was one of the best of his life. After landing in Paris, another plane took him to Tbilisi, Georgia. Katya arrived to meet him. They spent the next few nights at a hotel.

Facing Ryan in the interview room, Vande Kolk thought he seemed different from the man he’d been communicating with online. This version of Ryan was arrogant, unable to conceal pride in his accomplishment. At times Ryan expressed regret, but these moments were overshadowed by his boasting.

Katya hadn’t liked his plan, Ryan said. Faking his own death was “pretty bad,” she told him, worse than divorce. But faking his death, Ryan said, “checked more boxes.”

“Talk to me about that,” Vande Kolk said. “Everybody’s a little bit perplexed as to why you took this path.”

“I guess in the end it came down to the feeling of failure in about every aspect of your life,” Ryan said. “Hoping to be remembered for the better things, not all the mistakes.”

When Ryan reached the point in the tale where he arrived in Tbilisi, Vande Kolk asked for more specifics about his planning. For an obstruction charge, he needed to get Ryan talking about whether he’d intentionally set out to convince the detectives that he’d drowned. “The amount of hours that I spent trying to disappear would blow your mind,” Ryan said. His entire plan, he admitted, had hinged on him dying in the lake. “Obviously the whole idea was to sell the death,” Ryan said.

That oughta do it, Vande Kolk thought.

Sergeant Ward was watching the interview on a monitor down the hall. He’d spent the most time on the lake looking for Ryan. He’d watched Emily absorb the news that her husband was dead, then struggle to grasp the news that he was not. With all the money the county had spent on the search, it could have bought a new snowplow and fixed a lot of potholes. One reason he was not in the interview room was because everyone knew he’d have a hard time hiding his disgust.

Some of Ward’s disgust was with himself for having gotten played. Of course, he wasn’t the only one who’d been duped; Ryan had deceived everyone close to him, along with the general Green Lake County community. Ward liked to say that if you got a flat tire in Green Lake, there would be a traffic jam of people stopping to help. Ryan had exploited that kindness. All because he didn’t have the guts to look his wife in the eye and say, “I want a divorce.” He’d chosen to make himself a blameless drowning victim in the memories of his children.

Ward followed intently when Hanson began asking Ryan about the roughly $20,000 he’d taken from his own family in order to help a woman he’d never met. Ryan said he was already in so much debt that $20,000 didn’t do much for him. Whereas for Katya, he said, that amount was significant.

But Ryan still owed hundreds of thousands of dollars. Emily, struggling to provide for three kids on her teacher’s salary, had begun accepting food stamps.

This is one of the most two-faced criminals I’ve ever met in 23 years of working in law enforcement, Ward thought.

“Listening to him talk, I get the willies,” he told me later. “He’s just a really devious person.”

After nearly three hours, Vande Kolk told Ryan he was placing him under arrest for obstructing an officer. Ryan seemed surprised and indignant: He’d talked to investigators as soon as they’d contacted him. He’d come to Green Lake and answered their questions. Vande Kolk explained that the obstruction charge was based on what he’d done at the lake, not how he’d handled himself afterward. He asked Ryan to stand and clicked the handcuffs.

Ryan spent that night in jail. The next day, he pleaded not guilty. He was released on a $500 bond. The same week, Emily filed for legal separation, calling the marriage “irretrievably broken.” She asked for sole custody of the kids.

337 Days

One morning this past July, I drove along a two-lane road surrounded by cornfields and arrived at the Borgwardts’ stone ranch house. Their minivan was parked out front, along with the trailer Ryan had used to take his kayak to the lake. Snapdragons bloomed in flower beds along the front walk.

Emily greeted me wearing shorts and a tank top, her shoulders tanned from working in the garden. We sat in the living room, where we could hear her daughter, 14, and a friend laughing as they swam in an aboveground pool in the backyard. Her younger son, 15, mowed the lawn out front. A basket of laundry awaited folding.

Emily told me that her younger son and her daughter had seen and texted with their father since he’d returned. Their older son, now 18, had refused to speak with him.

Ryan was living with his mother and stepfather in Appleton, an hour and a half away. He was not helping to support the family, Emily said. Since his return, Ryan had been by the house a couple of times. They were now texting regularly, and she sent him pictures of the kids. She described their relationship as amicable.

How is that possible?

She said that the man who’d faked his death in Big Green Lake was not the Ryan she’d known for 25 years. Not the one who’d played board games with the kids and coached their basketball teams. She still missed that man.

Their life in Watertown had been ordinary, maybe even dull sometimes. But for Emily, it had felt like enough. Looking back, she could see that she and Ryan had become a little more distant over the years, but in ways that she did not think unusual for busy parents.

Emily had filed for separation on the advice of a lawyer friend who worried that she might be affected by any civil or criminal judgments against her husband, and they were now legally divorced. But to her, their vows were a different matter. “I’m a Christian and I believe strongly in marriage,” she said.

I asked if she would consider reconciling. I assumed the answer would be a hard no. I was wrong. Emily said she would be willing to try, despite how much work that might take.

“We all sin,” she told me. “Some sins in human eyes are bigger than others, hurt more than others, have more consequences than others. But in God’s eyes, they don’t. A sin is a sin.” She added, “God forgives us for our sins multiple times every day.”

If God could forgive, so could she.

She knew some people would find that hard to understand. “He’s still the father of my kids,” she said, “and I don’t want that relationship to be more strained than it already is.”

379 Days

On Tuesday, August 26, Ryan sat beside his lawyer in Green Lake County Circuit Court. Judge Mark T. Slate had reviewed the agreement Ryan had made with prosecutors: He would plead no contest to obstructing an officer, spend 45 days in county jail, and pay $30,000 in restitution.

The judge turned to the district attorney, Gerise LaSpisa, who summarized Ryan’s ruse: how he’d taken out a life-insurance policy, reversed his vasectomy, transferred money overseas. “Certainly any criminal charge, conviction, and sentence that this court today hands down will not be able to come close to undoing the incredible damage that this defendant, by his premeditated, selfish actions, has done not only to his family, but our community,” LaSpisa said.

Ryan’s attorney, Erik Johnson, reminded the judge that his client had been charged only with a misdemeanor. “He came back from Europe to take responsibility for his actions,” Johnson said. He noted that Ryan had no criminal record and had already paid the $30,000 restitution. (Ryan has declined to say how he came up with the money.)

Judge Slate asked Ryan if he had anything to say.

“I deeply regret the actions that I did that night, and all the pain that I caused my family and friends,” Ryan said, looking uncomfortable.

When the moment of sentencing arrived, the judge surprised everyone: Noting that Ryan’s fraud had lasted for 89 days, from the day he disappeared until the day Vande Kolk emailed him, Judge Slate sentenced Ryan to 89 days in county jail, almost double what the prosecutors had asked for. Ryan needed to begin serving his time within 60 days.

For someone who’d attempted such an audacious caper, Ryan looked sad and small as he walked out of the courtroom, a middle-aged man scurrying off, bald spot shining, as a reporter followed him asking if he’d spoken with his kids.

380 Days

The next morning, I arrived at the Elsewhere Market & Coffee House in Oshkosh, about 30 miles northeast of Big Green Lake, where Ryan had suggested we meet. When I’d first emailed him, in April, he’d responded that he couldn’t discuss what happened, because he feared it would hurt his family. I emailed him again in July. “For the sake of my kids and Emily,” he replied, “I wish you’d find something else to write about”; he suggested Jeffrey Epstein or the Ukraine war. Still, we kept emailing, and as the sentencing neared, we got into a regular back-and-forth. He said that he found it almost impossible to talk about why he’d faked his death without discussing his marriage—but that if he did so, he knew it would sound like he was blaming Emily and painting himself as a victim. He laid out the narrative as he saw it unfolding on the news: “1) I’m the ‘bad guy’ in the story. 2) Absolutely NO ONE will want to question otherwise. 3) I NEED to be the bad guy in the story for my kids.”

He suggested that the story could be a cautionary tale for couples about the importance of communication in marriage. He seemed unable to resist shifting blame onto Emily. “Truthfully the very fact I could pull all of this off shows how little interest she had in my daily work,” he wrote.

As we sat eating breakfast, his eyes staring into the middle distance, he told me that he believed a spouse should be like a well you can draw from. “I went around thirsty,” he said.

What he meant was that meeting Katya had given him “the taste of someone caring again.”

Why not just get a divorce?

“Divorce hurts more than people think,” he said. “I was trying to protect the kids.” He said that his own parents had separated when he was 3.

Although he planned to stay with Katya—and, he implied, marry her—he hoped to repair his relationship with his children, he said. (Efforts to reach Katya directly were unsuccessful.) He’d been angry when the prosecutor announced in open court that he’d reversed his vasectomy, he said, because he worried that the kids would think he wanted to replace them.

“I guess I just didn’t feel like there was any other way,” he said.

He continued: “Kids grow up, and kids leave.”

A long pause.

“I like what I have now.”

The day of the hearing, Vande Kolk climbed into his truck and headed home, feeling melancholy.

At times he had wondered whether it might have been better if they’d stopped searching and just let Ryan’s story end—at least as far as his friends and family would ever know—there in the lake. But he’d had a job to do and he’d done it.

Vande Kolk thought again about the many hours he’d spent fishing instead of at home with his family. He wondered: Was this his own way of fleeing his life? So many mornings he’d crept out of the house at 4 a.m., leaving his wife and kids so he could indulge his own solitary quest to catch that trophy-size musky. He felt some guilt over that. But he also knew it was part of what made everything else work.

As the sun dropped low over the golden fields, Vande Kolk pulled into his driveway.

“Supper is ready,” his daughter texted.

“What is it?” he replied.

“Something amazing,” she wrote.

He could smell it as soon as he walked in the back door. His wife, who’d worked at the bank all day, had cooked the family meal: chicken-bacon-cheese casserole. The family sat together in the living room, chatting about their day as Wheel of Fortune played in the background. Later, maybe he’d mow the lawn, then fall asleep on the couch watching the Brewers game. Living an ordinary life that provided, he thought, everything that mattered.

This article appears in the December 2025 print edition with the headline “The Missing Kayaker.”

The post The Missing Kayaker appeared first on The Atlantic.