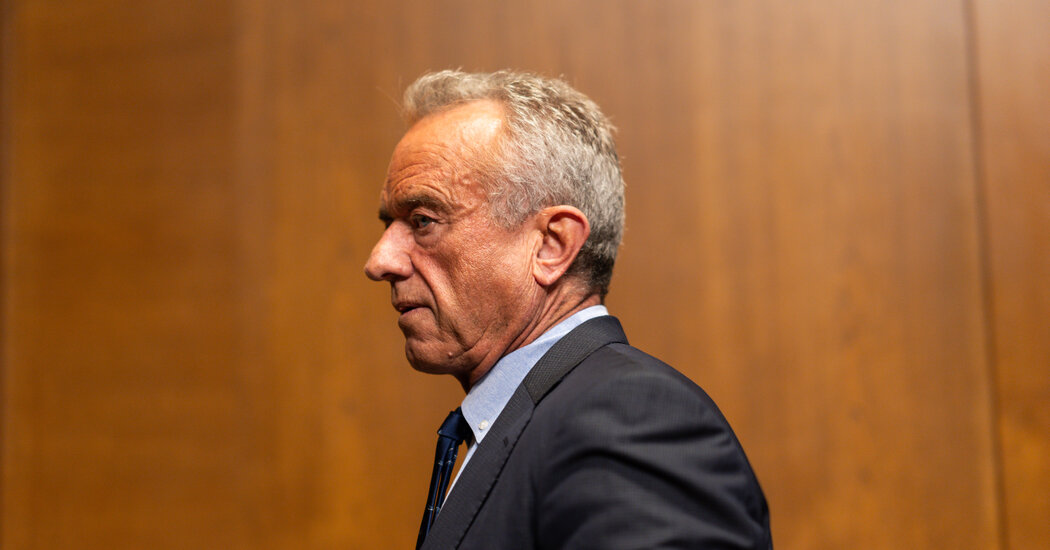

After months of shaking hands with Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and pledging to take artificial colors out of candy and drinks, food company executives are done playing nice.

In recent weeks, a coalition of food dye makers sued West Virginia, arguing that its ban on artificial colors is unconstitutional. In September, food companies opposed a California law that banned ultraprocessed food from school meals.

And a new organization called Americans for Ingredient Transparency, or AFIT, has emerged, seemingly endorsing Mr. Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again agenda. But AFIT is financed by a who’s who of food and beverage companies like General Mills, Hormel, Kraft Heinz and industry lobbying groups.

The boldest move so far is a push by the major food companies for federal legislation that would take power away from states that have been adopting tough new rules and would place it solely under the authority of slower-moving federal regulators.

The collision between Big Food and the MAHA agenda was inevitable. For decades, the industry enjoyed close ties with regulators and hired teams of lobbyists to win over key congressional members. The industry often succeeded in defeating proposals for stricter labeling or limits on certain ingredients like salt and sugar, and enjoyed a business-friendly relationship with President Trump during his first term.

That solid footing has weakened, now that Mr. Kennedy and MAHA are capitalizing on a growing national clamor for healthier options and are blaming Big Food for contributing to a variety of chronic health diseases.

State officials have embraced the MAHA momentum, creating a hodgepodge of new laws that may ban bright candy or neon-colored beverages in one state but not in another. The piecemeal approach raises costs for the food industry, which has been forced to try to figure out how to tailor thousands of products to deal with conflicting rules.

“I think the food industry has no choice,” said Stuart Pape, a former Food and Drug Administration lawyer who now represents food companies and their trade groups. “It can’t sit back and just take body blows and shrug their shoulders when state after state enacts inconsistent laws that make doing business impossible.”

AFIT said on its website that it wanted the F.D.A. to be “the sole entity” regulating the sale of foods and drinks in the United States.

To food safety activists, those are fighting words.

The F.D.A.’s food division has a long history of inaction. Some within the agency and in Congress worry that the division lacks funding for strong oversight, given that it is charged with regulating a global food supply on a budget roughly half that of the Dallas school district.

Making the F.D.A. the only sheriff in town — and invalidating a slate of state laws — would doom the MAHA movement, said Sarah Sorscher, director of regulatory affairs for the Center for Science in the Public Interest, an advocacy group.

“It would be like a Death Star for state consumer protections,” she said. “It would fly in the face of everything that Make America Healthy Again and activists have been fighting for and will be a complete betrayal of those grass-roots advocates.”

A few weeks ago, Vani Hari, an influencer known as Food Babe, said that she had become concerned that Senator Roger Marshall, Republican of Kansas and chairman of the MAHA caucus, was working closely with the food industry, particularly AFIT, on new legislative proposals.

“I was like, whoa, whoa, whoa,” said Ms. Hari, who has become a power player in the MAHA movement. “He can’t work with this group. It would completely undermine everything he has shown in the last several months as a MAHA caucus leader and undermine Secretary Kennedy’s work.”

In an interview, Senator Marshall said his office had meetings with various industry groups, including AFIT, but said they did not sway the bill. Still, an early draft of his bill, titled the Better Food Disclosure Act, included language to centralize power at the F.D.A. In recent days, however, Senator Marshall deleted that provision.

The senator said that he removed that section after he got an earful from MAHA moms who supported what various states were doing. “I couldn’t believe how much pushback I got,” he said. He added that there still may be a need for some national uniformity around rules.

He said he planned to introduce a bill this week that would address at least one of Mr. Kennedy’s priorities to add transparency for new ingredients added to food. It is unclear whether the bill would gain traction in Congress.

The behind-the-scenes clash illustrates the momentum building for change in the multibillion-dollar food and beverage industry.

“Our member companies remain committed to enhancing product transparency, innovating to meet the demands of consumers and working with the administration,” said Melissa Hockstad, chief executive of the Consumer Brands Association, a trade group.

Emily Hilliard, a spokesman for Mr. Kennedy, said that the Department of Health and Human Services would work with Congress to establish strong national food standards but would continue to back more local initiatives.

“We support states leading the effort to bring healthier food to families and children,” she said.

That recognition was publicly evident in late March, when Mr. Kennedy joined Patrick Morrisey, the Republican governor of West Virginia, at a news conference there to applaud passage of one of the nation’s toughest ingredient laws. The state banned seven artificial dyes from school lunches and would eventually eliminate them from the state’s food supply.

There, Mr. Kennedy recounted concerns that food company executives relayed to him during a meeting in Washington earlier that month: “Stop these governors from passing these laws because we don’t want a patchwork where West Virginia and California are banning food dyes and we have to make special products for those states.’’

“So they’re terrified of this, of what you’re doing,” he told the West Virginia gathering.

States as politically diverse as California, Louisiana, Texas and Arizona have recently passed laws to eliminate food dyes from meals served in schools. Texas and Louisiana required warning labels on food items that contain at least one of a list of 44 ingredients that are not approved in other countries.

This fall, California became the first state to pass legislation that would phase out certain ultraprocessed foods from school cafeterias. A long list of food industry trade groups opposed the bill over its definition of such foods, saying it was too broad and excluded nutritious foods such as yogurt and cheese.

In early October, the food industry began to mount additional efforts to fight back.

In West Virginia, the International Association of Color Manufacturers filed a lawsuit aimed at striking down the state’s new ban on seven artificial food dyes.

The lawsuit claimed that the state law had deemed the dyes “poisonous and injurious” without any evidence or justification, asserting that the F.D.A. and other authorities had concluded that the dyes could be safely used.

The organization did not respond to emails seeking comment.

Mr. Marshall’s bill would address an F.D.A. custom of allowing companies to add new ingredients to the food supply with no notice to the agency — creating a system of products laced with mysterious additives.

Known as GRAS, or “generally recognized as safe,” the agency’s provision originally allowed for items like vinegar and salt to be added to foods, but has since been used widely. The Marshall proposal would end the secrecy surrounding the introduction of new ingredients.

However, the proposal would give the F.D.A. only about six months to review each new ingredient, and includes few details about what information a company should disclose. Under the plan, the agency could file an interim notice of concern within six months and take another six months to make a final decision.

But given the thousands of notices expected to flood the agency, many ingredients might receive minimal scrutiny.

Mr. Pape, the food industry lawyer, said that such a plan might fail without increased funding. One possible source of financial backing could be a requirement for food companies to pay an annual registration fee for each of their large facilities, akin to the F.D.A. fees imposed on drug makers to review their products.

“If you put a funding mechanism in place like that, you could actually put expectations on the F.D.A. for food ingredient regulation that would be meaningful,” he said. “That would give you a serious argument that the state shouldn’t play in this space.”

Christina Jewett covers the Food and Drug Administration, which means keeping a close eye on drugs, medical devices, food safety and tobacco policy.

Julie Creswell is a business reporter covering the food industry for The Times, writing about all aspects of food, including farming, food inflation, supply-chain disruptions and climate change.

The post Big Food’s Fight Against Kennedy Is Heating Up appeared first on New York Times.