The critic and editor Malcolm Cowley had a record as a literary-talent spotter that was unmatched in the American Century. At The New Republic in 1930, where he’d recently become the literary editor at 32, he published “Expelled,” the first short story by a then-teenage John Cheever to appear in a national magazine (one that didn’t usually publish fiction). A few years later, Cowley gave a second teenager his start in reviewing: a Brooklyn boy named Alfred Kazin. In the 1940s, at the Viking Press, Cowley initiated the resurrection of William Faulkner from oblivion, a project that put the writer on the syllabus in the ever-expanding postwar university, brought the rest of his work back into print, and surely helped win him the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature. Cowley went on to battle reluctant Viking colleagues to ensure the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road in 1957. In 1960, he found Ken Kesey in a creative-writing class he taught at Stanford, and helped shape One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The journey from Cheever to Kerouac and Kesey, via Faulkner, was one that not many editors could have covered.

Nowadays some would call Cowley a gatekeeper, except that the term has acquired an invidious ring; Cowley’s power and influence lay in opening, not shutting, the door to a new generation. He came of age at an especially fertile literary moment, after World War I, and he had a special interest in the work of his contemporaries, in the homegrown modernism of Faulkner, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway. He had an even bigger goal as well, pursued in several now-classic works, starting with Exile’s Return: A Narrative of Ideas (1934). Cowley aspired to raise the status of American writing as a whole. He wanted to see it recognized as more than a mere appendage to British literature, as a great tradition in its own right.

If it seems strange that anyone ever needed to make such a claim, that’s a mark of how well Cowley and others of his era succeeded in their mission. Notable poets and novelists led the way. Scholars were close behind, among them the Harvard professor F. O. Matthiessen, whose American Renaissance (1941) established a canon that is still a basis for study. In between was the “man of letters,” a phrase that now sounds “cobwebby and antique,” Gerald Howard writes in The Insider: Malcolm Cowley and the Triumph of American Literature. But Cowley was on the cutting edge in his own time, as the biography vividly shows, focusing on his public rather than private life. Howard goes further: Cowley’s approach to American literature remains as important as ever to helping it thrive.

Howard is a publishing insider himself, now retired after a long career at Viking Penguin and Doubleday. He’s watched literary trends come and go, and writes in his introduction that he has been an admirer of Cowley’s work ever since he read his A Second Flowering: Works and Days of the Lost Generation (1973), published soon after Howard graduated from college. What that book taught him, he writes, was “a fact my otherwise excellent undergraduate English courses had failed to address: that writers were actual people.” Howard’s literature classes, like mine at roughly the same time, had yet to be overtaken by critical theory, but were under the sway of what was called New Criticism. Its practitioners were devoted to the close reading of texts, independent of their authors’ social and historical circumstances. Cowley, by contrast, was drawn to real-life context, and intuitively guided, Howard writes, by a “generational sense of the progress of American literature.” In that unfolding lineage, Cowley discerned an enduring set of almost mythic “commonalities,” among them a focus on rural life, a heritage of Puritanism, a “revolt against gentility”—and, of special importance to him, an ambition to give fictional form to this country in its notable disparateness.

For Cowley, born in 1898 and reared in Pittsburgh in a middle-class family without much money, taking a break from college proved formative. One “striking aspect” of his Harvard education, begun in the fall of 1915 (his tuition largely covered by scholarships), was “how completely free of any formal classroom encounter with American literature it was,” Howard writes. Matthiessen said the same of his Yale training around the same time. T. S. Eliot, who would become the most famous writer among Harvard’s recent graduates, was already busy turning himself into an Englishman.

Cowley went down a different path. He left school as a sophomore to join the ambulance corps run out of Paris by the American Field Service. Once he got to France, he found himself driving trucks loaded with munitions instead. Other future writers took a similar route to the war. E. E. Cummings and John Dos Passos were also volunteer drivers in France, and Hemingway was badly wounded driving on the Italian front, an experience that went into A Farewell to Arms. After spending the summer and fall of 1917 behind the wheel, Cowley failed the physical to become a fighter pilot. He was soon back at Harvard, but the brief experience convinced him that his own war-marked cohort knew a world of sudden and radical change that the literary generations preceding and following them didn’t.

Cowley graduated in 1920, and for a year and a half lived an adventurous, impecunious Grub Street life in New York, before a fellowship took him, now married, back to France for a master’s in French. But the real allure was the cafés of Montparnasse and the company of his generation, the one Gertrude Stein called “lost.” He later wrote amusingly about his only meeting with James Joyce, who sent him out to buy stamps. Cowley got arrested one night when he and some well-buzzed friends, the poet Louis Aragon among them, decided for no good reason to assault the proprietor of the Café de la Rotonde. It wasn’t Cowley’s idea, but he threw the punch, and the French police gave him a beating in turn.

“It was a boast at first,” the idea of a Lost Generation, “like telling what a hangover one had after a party to which someone else wasn’t invited,” Cowley writes at the start of Exile’s Return, his study of the expatriate American writers with whom he had shared the experience of the war, and then Paris in the 1920s. Exile, or rather expatriation, he saw in retrospect, gave an American literary generation—its members sharing middle-class origins and mostly university educated—a chance to play at la vie bohème in a country where the dollar went far. That life had its casualties. Cowley’s marriage later collapsed; his ex-wife moved in with his friend Hart Crane and was with Crane on the ship from which the poet jumped to his death.

It also postponed, Cowley wrote, the social and individual “emotional collapse” that followed a war that had left his generation of writers stranded and restless. Their ties to region and tradition, and to received truths, had been eroded, and they now confronted their own version of the American artist’s problem: what kind of creative life to stake out in a country lacking an established literary heritage. Nathaniel Hawthorne had struggled with that, as had Henry James. Cowley’s disillusioned but fundamentally idealistic cohort had an unexpected response. Shaped though they were by their European experience, they refused the path of permanent expatriation and, embracing a Modernist spirit of experimentation, reaffirmed their own Americanness instead.

Exile’s Return has been in print for almost a century, but Cowley’s other work of the period hasn’t aged so well. By that I mean his political work. He had always been on the left, but in 1932, he went to report on the strike-ridden coal mines of southern Kentucky, and found himself facing a heavily armed force summoned by local authorities. The experience made him distrust the entire American social order, and Howard is clear-eyed in his criticism of Cowley’s swerve into willful naivete about Stalinist Russia; it took him years to admit that the Moscow show trials really were a show. Cowley paid for his extreme credulity during World War II, when he was denied any real role in the war effort, and when the anti-Stalinist-left editors of Partisan Review and, later, The New York Review of Books had no space for him in their pages.

Yet this is when Cowley really begins to matter in American literary history. He retreated to a Connecticut farmhouse and immersed himself in reading—all of Faulkner, among other things—supported by a fellowship from the Bollingen Foundation. Cowley became convinced that Faulkner (whom he met only later) was misunderstood and undervalued. The separate books he had set in his imaginary Yoknapatawpha County were really parts of one enormous whole, Cowley recognized, and anyone who looked at them that way could see the unmatched scale of his achievement. In the mid-1940s, Cowley had a chance to illustrate that claim: He added a Faulkner volume to a Viking series called the Portable Library, anthologies that offered a selection of an individual writer’s best work. He had already done The Portable Hemingway, and in an introduction, he presented that ever-popular writer as far more traumatized by his war experiences than he was commonly held to be. Faulkner was a harder case; all but one of his 17 books were out of print. Cowley had to convince Viking, which went on to hire him as a consulting editor, that such a volume not only was needed but would sell; he had to make the case that Faulkner counted, and explain why.

By now, Cowley knew how to seed the market, and he wrote a series of articles for The New York Times Book Review and elsewhere that suggested a boom of interest in the southerner’s notoriously difficult work. Soon enough that boom did in fact begin, both here and in France, where, Jean-Paul Sartre told Cowley, young French readers saw the Mississippian as a “god.” The Portable Faulkner appeared in 1946, and in stressing the linked plots and characters of the different novels, Cowley’s introduction showed how the writer had created “a parable or legend” of a white South whose self-regard was indelibly stained by the sin of slavery. The Portable series itself would eventually branch out from hardcovers and become part of the paperback revolution that put cheap editions of classic literature into the hands of millions.

As a critic, Cowley arguably made his most valuable contribution when he set out to anatomize the emerging postwar cultural scene in the U.S., a world in which he played a pivotal part. In The Literary Situation (1954), Cowley, the earlier champion of American experimentation, identifies an uneasy “interregnum,” during which writers were “looking for something or someone to give their work a more definite direction,” even as the country’s readership was democratizing. He tours the revolving book racks in Chicago drugstores, finding softcovers both pulpy and serious.

Thinking, as always, in terms of literary generations, Cowley devotes key chapters to fiction that came out of World War II, surprised that books such as James Jones’s From Here to Eternity and Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead are more formally tame than those written after his own war, their realism less touched by modernist symbolism. He heralds Saul Bellow and Ralph Ellison as the most daring new novelists of the 1950s, struck by their sprawling books’ success in homing in on the particulars of Jewish and Black experience while also examining “the dilemma of all men in a mechanized civilization.” It’s worth noting that Cowley had by then begun the challenging work of bringing Kerouac’s account of crisscrossing the American landscape into print. His more conservative Viking colleagues questioned the project’s merits; Cowley was enmeshed in its difficulties. He had to preserve narrative spontaneity while avoiding potential libel and obscenity charges. Pulling off the feat took years.

Cowley ends his examination of the postwar cultural situation on a note of doubt, not least about the changing status and nature of literary criticism. “It may be hard to credit now,” Howard writes, “but the route to real literary prestige and advancement once ran through the practice of book reviewing”: To be an influential arbiter had meant to write for a nonprofessional public in the pages of magazines and newspapers, as Kazin did, and Edmund Wilson, and Cowley himself. Criticism was now migrating to the university, and its focus was on the work as an “entity with its own laws of being,” and fundamentally divorced from any “moral or social” effect, as Cowley put it. He admired the precision that such academic critics brought to the analysis of language. But he also found the approach sterile, out of step with a literature that he felt thrived on engaging with the unfinished and upstart project of the nation: How could one possibly understand Leaves of Grass or The Great Gatsby in purely formal terms?

And how could an American literary tradition claim the distinction and stature he felt it deserved without the animating idea of the Great American Novel? Cowley’s own career had been galvanized by the arrival of just that. As of 1920, he writes in The Literary Situation, there was as yet “no American novel that was great in the sense of being greatly admired,” and acknowledged as such by “the educated public”—a work that embraced not just a region of the country but its expanse. A few years later, there was. It was called Moby-Dick. Cowley saw its elevation to the “position of national epic,” more than half a century after it came out in 1851, as the most significant literary event of his own time, even more important than the recognition bestowed on Faulkner and Hemingway.

Cowley died at 90, well aware that his own Lost Generation had itself long since become a myth. Was he a great American critic? Not as great, in Howard’s final judgment, as his friend Wilson, whose polyglot sense of literary history had a global range. But Cowley was American in a crucial way, wearing many hats in his long career, fascinated by the country’s parts, and always seeking to understand the forces that kept it whole and the writers who shared that curiosity.

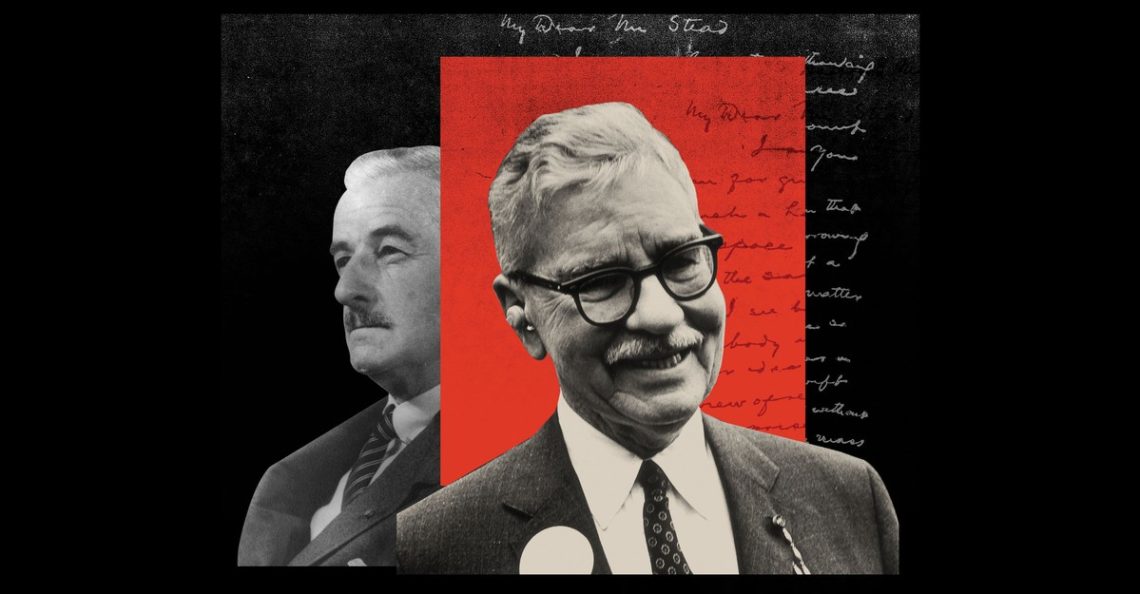

* Lead image sources: Carl Van Vechten Collection / Getty; Fred W. McDarrah / The New York Historical / Getty.

This article appears in the December 2025 print edition with the headline “The Man Who Rescued Faulkner.”

The post The Man Who Rescued Faulkner appeared first on The Atlantic.