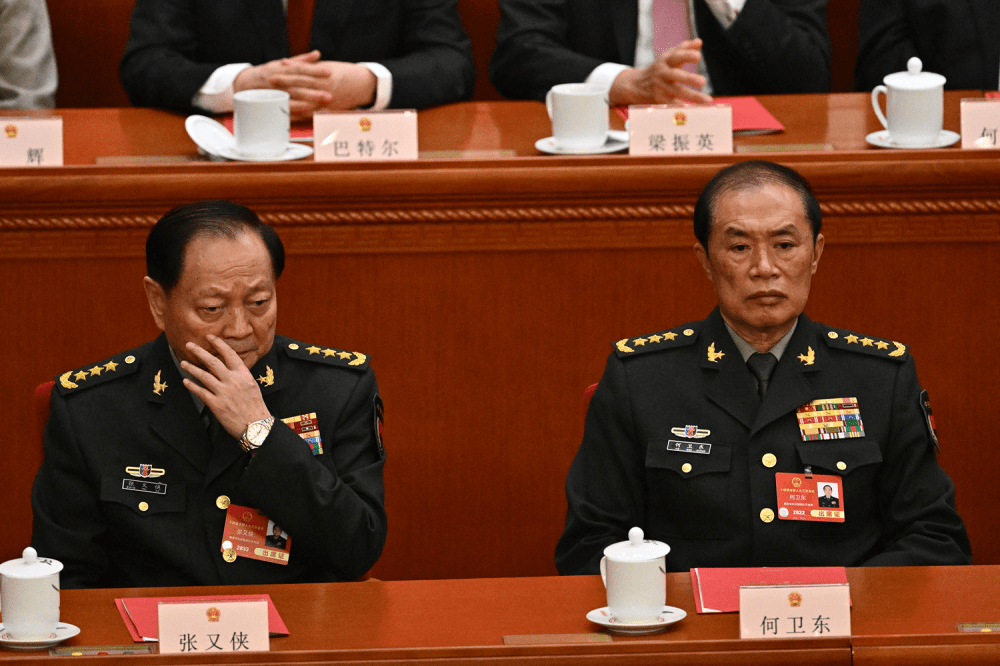

China’s military recently expelled nine top leaders from both the Communist Party and the armed forces, including Central Military Commission Vice Chairman He Weidong and chief political commissar Miao Hua.

In the past few years, successive defense ministers, Li Shangfu and Wei Fenghe, were purged; before them, former Central Military Commission (CMC) Vice Chairmen Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong fell. Counting the many other officers expelled since President Xi Jinping came to power more than a decade ago, one could almost line up a platoon of purged generals.

The ousted leaders have come from the very core of China’s defense establishment. Such sweeping purges should have provoked fierce institutional backlash or political shock waves. Yet, despite the flood of coup rumors circulating in overseas Chinese media, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has remained placid, perhaps even more politically uniform than before.

The PLA’s official mouthpiece published several commentaries before and after the recently held Fourth Plenum, an important Chinese Communist Party meeting, reiterating that “the party commands the gun, and the gun must never command the party.” It stressed that the entire military must obey the leadership of the chairman of the Central Military Commission. The paper portrayed the recent investigations of senior officers as evidence that the CMC remains the ultimate source of political authority within the armed forces.

Many observers find this puzzling. Questions often surface in my conversations with Chinese scholars and across Chinese-language discussions on X: Why do the kind of coups that erupt in semi-authoritarian or immature democratic regimes never seem to occur in China?

Perhaps the downfall of the Gang of Four in 1976 could be seen as an exception, but the purge of this group of radical leaders who had risen during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) occurred in the unique historical vacuum that followed Mao Zedong’s death. Even then, it hardly qualified as a military coup.

Those arrests were carried out under the authority of Hua Guofeng and Ye Jianying—at the time, the legitimate leaders of both the party and the People’s Liberation Army—thereby reaffirming the norm that the gun serves the party, not the other way around. Are Chinese generals simply cowards, afraid to die? Fear, of course, is a factor—but not the decisive one.

The PLA’s failure to act is a result of institutional structure, not personal psychology. The Communist Party’s doctrine that “the party commands the gun” makes it impossible for the PLA to evolve into an independent political entity, and Xi has taken this dependence to its absolute extreme.

Strictly speaking, the PLA is not a national army, although it acts as one. It is a party army—the private armed force of the Chinese Communist Party. From the very beginning, when Mao created the Red Army, he inscribed the dominance of the party into its DNA. That principle has remained intact for nearly a century and is the PLA’s political foundation.

But this is not a mere slogan; it is a fully institutionalized and tightly sealed system. It ensures that the soldier’s ultimate loyalty is not to the constitution or the state but to the Central Committee and, ultimately, its supreme leader. Every decision on operations, promotions, training, and political education must serve the party’s needs.

This logic is built into the very architecture of command: From the CMC down to theater commands, group armies, and brigades, every level has political commissars and political officers responsible for ideology, organization, and personnel. In a system copied directly from the Soviet Union, these commissars report directly to higher-level party committees, not to military commanders.

This dual-leadership structure guarantees that military action is always subordinate to political intent. The PLA is not a neutral national institution but, rather, the armed wing of the party; its real center of gravity lies in its political work system. Even on the battlefield, a political commissar has the power to veto a commander’s order. Such an arrangement erases the possibility of autonomous military authority—the concrete meaning of “the party commands the gun.”

The purpose of this principle is to keep the army firmly under party control and prevent soldiers from meddling in politics. Although the CCP came to power by armed struggle, after 1949, the military was kept strictly subordinate to the party, forbidden to intervene in intraparty disputes over policy or leadership—except in rare moments such as parts of the Cultural Revolution.

To institutionalize this subordination, China’s top leader has almost always served simultaneously as both party general secretary and commander in chief of the party’s armed forces. CMC Chairman Deng Xiaoping was a partial exception, but even then, the party elite reached a tacit consensus that Deng was the ultimate decision-maker in party affairs. Thus, he remained the de facto supreme leader, even without holding every formal title.

For officers in the PLA, career advancement depends entirely on the party organization within the armed forces. Political departments keep exhaustive records of each officer’s ideological attitude, family ties, and behavior; any deviation can destroy a career. Over time, this has bred a deep psychological dependency. Through vertical control of appointments, the party has bound the military into its political system, turning it into an extension of party power.

This mechanism has erased the army’s internal autonomy and horizontal cohesion, leaving no foundation for collective dissent. The experience of Lin Biao—the marshal once designated as Mao’s successor and the PLA’s deputy commander—illustrates this perfectly. When Lin’s son, Lin Liguo, discovered in 1971 that Mao had turned against his father and that the family’s future was in peril, he plotted to assassinate Mao. Yet even he dared to confide only in a handful of associates; he could not risk alerting other loyalists. Today’s generals command nothing like the networks or loyalties that Lin Biao once possessed. Their careers are entirely at the party’s mercy.

After Xi came to power, this system was pushed to its political extreme. The sweeping military reforms launched in 2015—the most far-reaching since the founding of the People’s Republic—were presented as an effort to enhance the PLA’s joint-combat capability, but they also entailed a major redistribution of military power.

The old seven military regions were replaced by five theater commands whose commanders report directly to the CMC. The four powerful general departments—General Staff, Political Department, Logistics, and Armaments—were abolished and replaced by 15 CMC departments. All authority was recentralized under the CMC.

On the surface, these were administrative reforms; in reality, they were deeply political. They shattered the regional patronage networks that had formed over decades, and prevented any general from building an independent base. The old internal balance of power was destroyed and replaced by a single, centered structure: All authority flows upward to the CMC chairman himself.

Within this framework, Xi turned his supremacy as CMC chairman into the PLA’s ultimate political rule and an operational reality. Previously, while the CMC chairman nominally held ultimate authority, vice chairmen and the general departments enjoyed significant autonomy, and major decisions were made collectively. Xi changed that. All matters—military, political, personnel, or disciplinary—must now be submitted for the chairman’s personal approval; other members may advise but cannot veto.

The chain of command has become a straight vertical line, eliminating lateral checks. After the reforms, officers’ promotions, assignments, and even family privileges depend directly on their loyalty to Xi. Political performance has overtaken professional merit as the key criterion for advancement. The slogan “absolute loyalty, absolute purity, and absolute reliability” is drilled into every officer and has nearly replaced the traditional code of military honor. In effect, Xi has not only restructured the army but also reshaped the political character of its personnel.

Given this institutional setup, even the harshest purges will not trigger rebellion. There are three further factors at work.

First, Xi’s purge has been cloaked in the legitimizing banner of anti-corruption. The PLA’s corruption has long been an open secret. While public enthusiasm for Xi’s broader anti-graft drive has waned, no one sympathizes with generals accused of trading promotions or pocketing arms-procurement kickbacks. Xi’s “tiger hunts” thus align with the public’s moral sense and with the party’s own definition of political rectitude.

Regardless of his true motives, once a target is branded “corrupt,” he loses any claim to fairness or solidarity. Within the party’s political language, anti-corruption equals purity; opposing it equals disloyalty. The logic is self-sealing. Purges become opportunities to reassert discipline, and any misgivings within the ranks find no legitimate outlet. The anti-corruption narrative is politically bulletproof.

Second, Xi has reinforced ideological control across both the party and the military. Since the 18th Party Congress in 2012, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, the CMC’s own discipline commission, the propaganda apparatus, and the political work system have collaborated to monitor ideological trends among officers. Internal regulations forbid “improper discussion of the Central Committee” and “the dissemination of unverified information.”

Political discipline and political rules now override all others. Cadre evaluation systems have been reengineered so that political loyalty is the decisive measure. Even an inadvertent slip can end an officer’s career. In this environment, the organization produces its own muting effect: dissent is preemptively self-censored. Soldiers learn to be silent—and to find safety in silence. Public professions of loyalty are the safest speech. Over time, this creates a political culture of outward unanimity and inward caution. What outsiders might call intellectual paralysis is, within the system, the very logic of survival.

Third, the purge operates as a mechanism of institutionalized fear. Each time a senior officer is felled, the military launches new “self-inspection” and “warning education” drives. Cadres must write repeated self-criticisms and declarations of loyalty to prove their political firmness. These ritualized campaigns remind everyone that any ambiguity of attitude can be interpreted as betrayal.

The effect is the opposite of defiance: It is a race to display obedience. Political security becomes synonymous with personal safety, and loyalty becomes the most rational form of self-preservation. Through this cycle, fear becomes normalized as a governing tool. The asymmetry between risk and reward is overwhelming—silence guarantees survival, speech guarantees destruction. The generals are not ignorant of this dynamic; they understand it perfectly.

Seen through this logic, Xi’s ability to purge so many generals without provoking institutional backlash is neither accidental nor the product of exceptional charisma. It is the natural consequence of the CCP’s system of control. The party’s principle that “the party commands the gun” eliminates the army’s political subjectivity, the institutionalization of the chairman responsibility system completes the personalization of command, the moral authority of anti-corruption provides the legal and ideological cover, and the party’s centralized discipline leaves no room for dissent. These elements interlock to form a closed political order in which the army is not an autonomous force but an institutional embodiment of the supreme leader’s authority.

The generals’ refusal to resist is thus not simply a matter of personal fear but a structural inevitability. The CCP’s political logic does not rely on the will of individuals; it relies on organizational control. The PLA’s stability arises not from genuine unity of conviction but from the prior elimination of any alternative.

Xi’s system of command represents the final form of “the party commands the gun”—power no longer divided between party and army but fused into a single core. For the regime, this ensures the highest degree of political security. For outside observers, it reveals something deeper: In a fully party-controlled military, rebellion is not merely unlikely. It is conceptually impossible.

The post Why Are China’s Generals So Quiet as Xi Purges Them? appeared first on Foreign Policy.