Photographs by Pat Martin

Not long after I walked through the open door of Thomas McGuane’s Montana farmhouse, his dog Cooper at my heels, he ushered me back out for a tour of the ranch and the trout-studded freestone stream that bisects it. It occurred to me to ask if I should be watching for rattlesnakes as we pushed through the brush in the sweltering heat. McGuane told me there was nothing to worry about, then added that he had stepped on, and been bitten by, a rattlesnake the year before last. “That’s how I learned I need a hearing aid,” he said dryly. He apologized for being an unsteady walker, though I was having trouble keeping up with his brisk pace across unfamiliar terrain.

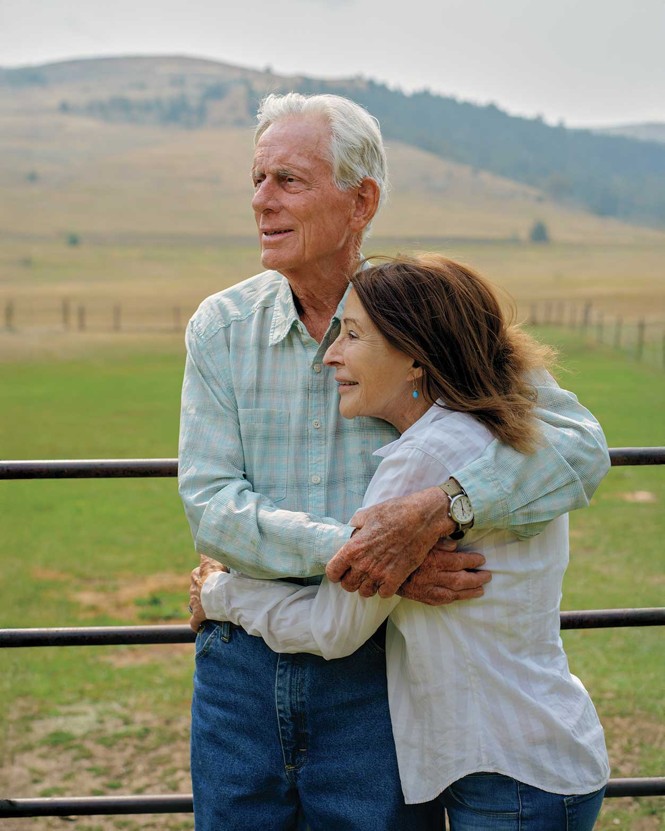

McGuane, an athletic 85, lives on 2,000 acres of rolling prairie in the Boulder River Valley, 75 miles east of Bozeman. Along the back roads that lead to his property, which is in the remote community of McLeod (one bar, one post office, population 162), quarter-mile-long irrigation systems sprayed huge, unattended agricultural fields. And everywhere, in every direction, cattle. In preparation for the trip, when I’d asked if there was an address to put in my GPS, I’d been rebuffed: “There’s not.”

I’d ostensibly arrived here to interview McGuane about his new collection of short stories, A Wooded Shore. The more honest truth is that I was in McLeod because I am a fisherman and a writer, and had come to pay homage to the master. McGuane, who possesses the singular distinction of being a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Fly Fishing Hall of Fame, and the National Cutting Horse Association Hall of Fame, is the author of 10 novels, four story collections, and numerous essays, most of which are, directly or indirectly, about the sporting life. He is arguably the only major American fiction writer still living whose work is inextricably connected to fishing, hunting, and ranching. And he may be the last.

McGuane is reflexively compared to Hemingway, and it is not hard to see why. Obsessed anglers who lived in Key West, and whose fiction sometimes gravitates toward horses, blood sports, and male protagonists with a masculine swagger counterbalanced by a certain reflective, existentialist temperament—the similarities between the two are obvious, yet go only so far. McGuane’s style has at times skewed maximalist, a stark departure from Hemingway’s famously undecorated prose. His fiction is also considerably more droll.

And unlike Hemingway, who tends to be fixated on honorable men thrust into, or just emerging from, Big Moments—frequently war—McGuane is interested in large-souled men in smaller moments. They’re adrift, spiritually and socially, and look for solace in wild places, though that solace is usually troubled by the realization that the wilds, and the ways of life built around them, are disappearing. This is no doubt one reason his work is so beloved among outdoors enthusiasts.

When I told a few fishing friends that I was going to meet McGuane, they reacted as though I’d declared that I was making a pilgrimage to see Bruce Springsteen, or Barack Obama, or the pope. But when I relayed the same news to some nonfishing acquaintances, including a few writers, their responses were mostly versions of “Who?” or “Oh right, him.” Today, far more Americans inhabit urban and suburban terrain than when he began writing fiction half a century ago, and participation in hunting and fishing has been declining for decades. No wonder, perhaps, that an audience for his remarkable body of fiction has not kept up with him—avid though his readership once was.

His most famous novel, Ninety-Two in the Shade (a 1974 National Book Award finalist), is nominally about a Key West burnout whose determination to become a local fishing guide leads him to ruin. In a deeper sense, it’s about being a man with no good wars to fight, no great causes to cling to, and no duty that calls him in a culture whose norms and customs are in flux. “Nobody knows, from sea to shining sea,” its memorable opening line reads, “why we are having all this trouble with our republic.”

The “trouble” in question is of the hangover-from-the-1960s variety: the drugs, the free love, the feminism, and, though this is left unspoken, the ways America had been shattered by Vietnam. As in much of McGuane’s fiction, the natural environment—in this case, the vitreous Florida flats, and the angler-tormenting tarpon, permit, and bonefish that populate them—provides the foil. In this novel, as well as in others McGuane wrote during the ’70s, amid his annual peregrinations to Key West, the coastal world is a place of sense-making and ecological order. Its regularity and rhythm cut against a helter-skelter modernity that has neither.

A tension between humanity’s chaos and nature’s equipoise continued to define McGuane’s fiction as he entered his Western period in the 1980s, when he began to set all of his novels in Montana. Something approaching ecological grief now surfaced in his work, a sense that Big Sky Country’s outdoor life—and with it, the folkways of people who beat the sun to rising and who know how to shoe a horse and gut and pack out an elk—was becoming gradually impossible, or at least unappreciated. McGuane’s style grew less frantic, more habitually elegiac. An old man puts eggshells in coffee grounds—“cowboy coffee.” An aspiring rancher, the protagonist of Keep the Change (1989), is clear-eyed enough to know that the livelihood he’s chasing is an anachronism. The young man grows ruminative as he watches the weather from his family’s porch. “This may be the principal use of a cattle ranch in these days,” McGuane’s wannabe cowpoke reflects: “watching the weather.”

In A Wooded Shore—a collection of five New Yorker stories from the past half decade, one story that appeared in The Paris Review in 2020, and three never published before, including the title story—McGuane has mostly turned away from spectacular landscapes as well as the aimless 20- and 30-somethings groping for purpose who defined his early fiction. Indeed, his protagonists are now mostly men stuck in middle age or older, who have realized that purpose has permanently eluded them. Strip malls, dull office jobs, emptied-out prairie towns, and frayed families dominate the foreground. For his characters, fishing and hunting are hobbies, not burning obsessions. These characters often reflect on the past—theirs, their fathers’, their country’s—and feel regret.

In this way, McGuane has kept pace with America’s shifting social landscape even as he remains a devoted outdoorsman in his private life—and even as the fiction-reading public now skews heavily female, a less obvious target for novels like his. Yet to call McGuane an unsung writer is not quite accurate, of course. Three of his novels have been made into movies, and his bacchanalian Key West tarpon-fishing exploits with his now-deceased artist friends—the writers Jim Harrison and Richard Brautigan, as well as the singer Jimmy Buffett, whose sister Laurie is McGuane’s wife—are detailed in a documentary called All That Is Sacred, which became a cult hit after it was released in 2023.

McGuane has his devoted fans, but as we continued our ramble along the stream, I asked myself what had happened to the Great Outdoorsman Novelist, a variety of literary man who once seemed commonplace but now is an endangered species. And what will we lose when he’s gone?

McGuane’s eyes remained fixed on the water. If you are a fisherman, it’s reflexive and involuntary, and he can’t help himself. I followed his index finger as he pointed to a deep trout lie shaded by a rock face, to a lazy pool that’s fishable even when the current is running hard with snowmelt, to a glassy bend where insect hatches are sometimes visible from his writing room.

McGuane does his writing in an old bunkhouse for cowboys and ranch hands that he appended to his farmhouse a quarter century ago. Above the bookshelves he still keeps a fly rod hanging on two pegs, ready to go in the event that, sitting at his desk, he spies rising fish. “The thread is the river,” his oldest daughter, Maggie, later told me, summarizing McGuane’s life: Across nearly nine decades, fishing has been the through line of his existence.

He was born in Wyandotte, Michigan, in 1939, the son of Irish Americans, a fly-fishing father who was fond of drink and a mother who was fond of books. These passions—reading, fishing, booze—later became McGuane’s own, ones that he has, with the exception of alcohol (he is now decades-sober), maintained with a kind of vocational intensity that would feel more at home in a monastic order. As his life and books betray, that sense of focus didn’t always dominate. “I was the kind of kid who today would be on Ritalin,” he told me as we sat in his television-less living room drinking homemade iced tea. Fishing with his father and grandfather was a welcome release, but school brought out his inner troublemaker. Eventually he was shipped off to boarding school, where he won the approval of the librarians if not the teachers: “I was always the only person in the library.”

College (he bounced around among a few) was a similar story. McGuane recalled nights spent closing out the bars and talking books with Harrison, whom he met at Michigan State University. The pair would then make their way to the nearest trout stream, fly rods in hand, and wait for the sun to come up. They’d fish through the morning, often still wearing off a drunk.

“My twenties were entirely taken up with literature,” he later said in a Paris Review interview. After getting a bachelor’s degree in humanities at Michigan State in 1962, he went on to earn an M.F.A. at Yale three years later, intending to be a playwright. McGuane realized that he wasn’t willing to live in New York City—a necessity to make it in the theater world. He decamped to Stanford in 1966, the recipient of a prestigious Stegner Fellowship for early-career writers. For a man who described himself in the same interview as driven by “fear of failure,” it seems to have been a well-timed goad: He began work on what became his 1968 debut novel, The Sporting Club. Devoted though he was, spending hours every day writing, he took to steelhead fishing more than to California literary life. “My usual schizophrenia set in,” he told me of those restless years, and he headed off to Livingston, Montana, a town he landed on after a San Francisco fly-shop employee recommended it. “I had no good reasons to assume that I had any kind of remunerative future,” he said. “But I had about $600 left. And so I said, ‘Well, until the axe falls, I’m going fishing with the $600.’ ”

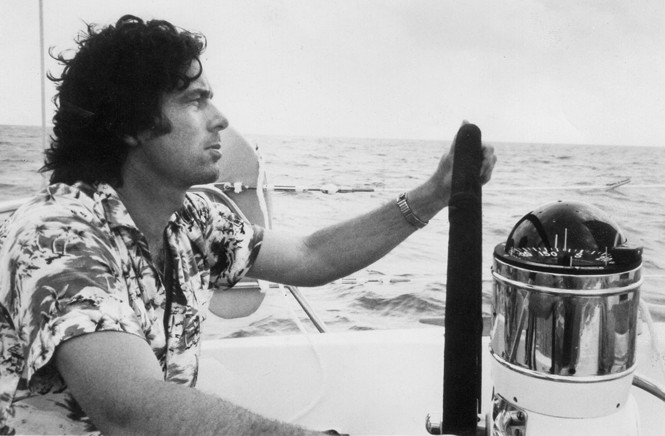

By then, he’d married a woman from Kalamazoo, Michigan, named Portia Rebecca Crockett and had an infant, and when his new Livingston neighbors, perfect strangers, brought his son a rabbit and a cake for his first birthday, McGuane and his wife decided not to move on as planned. “I thought, God, this was nice. Maybe we’ll stay for another month or two ’til I figure out what I’m doing with my life.” What he wanted to do with his life, he soon concluded, was fish: “I was just a fish head,” he said ruefully. Around the same time that he settled down in Montana, where he took up cattle ranching and has remained ever since, McGuane found himself also regularly spending months in Key West, plying his fly rod in the salt. His reputations as a gifted fisherman and a gifted writer—pursuits that became ever more entwined—were cemented during the 1970s as he began what became an annual migration: heading south to fish for tarpon in the late winter and early spring.

Hemingway was a decade dead, but other literary giants remained in the Key West orbit. McGuane joined Tennessee Williams for some meals, discussed writing with Hunter S. Thompson, and went drinking with Truman Capote, whom he described as a mesmerizing dancer. But this older and more established generation didn’t define his Keys experience. His gang consisted of a younger circle of fisherman-writer friends: Harrison, a passionate, if middling, fisherman who would later publish Legends of the Fall; Brautigan, the author of the celebrated 1967 novella Trout Fishing in America; and Guy de la Valdène, a French writer, sportsman, and Norman count. McGuane—whose friends had earlier dubbed him the “White Knight” for his literary dedication and comparatively straight-edged lifestyle—began cutting loose, though angling remained his main diversion from sweating out prose. They would meet in Key West almost every year and fish for tarpon almost every day—hungover or coming off some drug or another consumed the night before.

Here, McGuane’s legend was built. He became known not just as a world-class fisherman, but as a reliable good time—“Captain Berserko” was his new nickname. He made money on the side as an intermittent tarpon guide, and in addition to novels, he wrote freelance articles for various magazines, some of which have become classics. I’m far from alone in considering “The Longest Silence,” his 1969 Sports Illustrated essay on stalking permit—a plain-Jane, silver-dollar-looking fish that would be perfectly unremarkable were it not arguably the world’s most challenging to land on a fly rod—the greatest fishing essay ever written. (“I was losing my breath with excitement”—McGuane has just spotted a permit trying to steal a crab from a stingray—and “the little expanse of skin beneath my sternum throbbed like a frog’s throat. I acquired a fantastic lack of coordination.”)

In these years McGuane also wrote Ninety-Two in the Shade, a snapshot of a lost Florida, when both the people and the coastline were still wild, before the money, the snowbirds, and the big-time cocaine dealers moved in. It also captured a lost literary subculture, a relic of a day and age when big magazines would pay big money for fishing features, and when up-and-coming writers could be found in tarpon skiffs rather than Brooklyn dives.

Ninety-Two in the Shade launched him into a tumultuous stardom. The rave reviews were followed by a stint in Hollywood—where he wrote and directed an adaptation of the novel—and, after his first marriage fell apart, an even briefer Hollywood marriage to the actor Margot Kidder. (After their divorce, Crockett married the star of McGuane’s movie, Peter Fonda.) McGuane’s literary swerve was even more dramatic. Like his two previous works, Panama—his fourth novel, published in 1978—is set in Florida. A feverish and lightly autobiographical work about a rock star with a drug problem and daddy issues, it was panned by reviewers as lazy and self-parodying.

McGuane has been frank about how devastated he was. “People don’t understand how much influence they can actually have on a writer, how much a writer’s feelings can be hurt, how much they can deflect his course,” he said years later in the Paris Review interview. “I was stunned by the bad reception of Panama; it was a painful and punishing experience.” He never set another novel in the Keys, and Panama was the last novel marked by the madcap lyricism of his 1970s writing, the last novel before McGuane got sober and, not unrelated, began taking his tarpon trips in other parts of Florida, away from that scene.

“To be as succinct as possible,” McGuane began when I asked him if he lamented the disappearance of fishermen, hunters, and other rugged sporting types from American literary culture: “No, and good riddance!” His booming laugh made it hard to tell whether he meant this half or wholly seriously. He pointed out that their extinction is only partially true, anyway. There are a number of fishermen writing superb literary nonfiction today, and McGuane mentioned three of my personal favorites: the bonefish-addled poet, trout guide, and University of Montana professor Chris Dombrowski; the fishing and fashion writer David Coggins; and Monte Burke, the author of Lords of the Fly, a beautifully written and meticulously reported book about tarpon fly-fishing in the Keys, in which McGuane is a minor character. But he conceded that novelists writing in this mode have essentially vanished, even if he didn’t view this development as some grand tragedy.

McGuane also reminded me that Hemingway was, to put it politely, a complicated personality, a domineering figure prone to brawling, affairs, and cask-strength egoism. “Until Bill Belichick came along, I can’t think of anybody more disagreeable,” he told me. Decades’ worth of Hemingway comparisons have plainly rankled McGuane, and after a few days with him, I understood more clearly why: The two men are not just stylistically but temperamentally worlds apart. McGuane’s cowboys lose fights—for women, for their ranches, for their dreams—and tend to know when they’ve been beaten. His fiction, neither notably blood-soaked nor mythologically freighted, also differs starkly from the work of Larry McMurtry and Cormac McCarthy, contemporaries who likewise were famously steeped in the West. McGuane, who’s lived Montana’s everyday reality in ways that they didn’t, is not tapping into the John Wayne version of the Old West. His cowboys keep their saddles in the back of their sedans.

Even at 85, McGuane is wiry and strong, a hard man who has—by his own choice—lived a physically arduous life as a working rancher: breaking horses, rising early to drive cattle, enduring snowed-in Montana winters miles from what would pass for most of his readers as civilization. He describes himself as a “recluse,” but he clearly doesn’t hole up on his property in remote McLeod. Everywhere I went—a bar, a Livingston restaurant, a Bozeman bookstore, a fly shop—I ran into someone who knew him and conveyed what I was discovering: how generous, funny, and kind he is. McGuane, who remains a gorgeous fly caster, spent an afternoon giving me patient lessons. He stood 10 paces off and had me go through the motions again and again, eyeing my backcast like a benevolent hawk until he was satisfied that I’d made progress.

Watching him hold a fly rod, shooting long, looping casts in the shadow of the little writing room he had built onto the house; seeing him beam at the sight of a fat, ruddy fox crossing a deer trail; hearing him recount catching a tarpon weighing more than 150 pounds at the age of 82, restoring a cow-trampled stream bank, and trudging down a grizzly-tracked switchback in a subarctic storm in pursuit of Canadian steelhead, I was struck by how rare men like McGuane are becoming. Perhaps he really does mean that we shouldn’t regret the disappearance of literary outdoorsmen. He seemed to harbor no special fixation on his cultural legacy. When I asked what he thinks of Taylor Sheridan’s Montana-ranch soap opera, Yellowstone, a TV series quite obviously influenced by McGuane’s Western fiction, he told me that he hadn’t seen it, though he recalled that the director did once visit his ranch to see his horses.

But perhaps—and this seemed to me more likely—this modesty is also something of a defense mechanism, a way of coping with a transformed culture that is not much interested in the knife-thin silhouette of permit on a shallow flat, the smell of sagebrush in the Montana backcountry, the way a pheasant folds and falls when it’s been hit cleanly with shot, or simply a red fox that has survived another winter.

When I left the ranch for the last time, the sky over the Crazy Mountains was clotted gray, then finally opened up. McGuane and his wife urged me to get on the road before the storm got too bad. They were worried about my “small” car, an SUV that didn’t feel small to me until I noticed the water lying in heavy pools on their unpaved road.

By the time I was halfway down it, the rain was slowing and the starlings that had amassed on the power lines during my drive in were now rioting, looting the ground for worms. “All signs suggest that we’re actually at war with the Earth itself,” McGuane observed in a talk he gave on fishing a few years back. That war felt a world away in McLeod, where the land still seems too big to be brought to heel, and people still live on rather than against it.

But as I drove by a celebrity-owned ranch, I was reminded that the war is coming for this place too, and is already being waged by profiteers, hobbyists, and speculators—“house flippers, ranch flippers, and river flippers,” as McGuane puts it in a story in A Wooded Shore. And when that war has reached a more advanced stage, when the wild is variously paved with hot asphalt or turned into Disneylands for the gawking rich, when few native trout are left in the freestone pools and the men who would throw dry flies at them are scarce, McGuane’s writing, if nothing else, will be left to remind us of what we’ve lost.

This article appears in the December 2025 print edition with the headline “The Last of the Literary Outdoorsmen.”

The post The Last of the Literary Outdoorsmen appeared first on The Atlantic.