On Oct. 29, 1975, President Gerald R. Ford stood at a lectern in an ornate ballroom at the National Press Club in Washington and calmly, deliberately assailed the leadership of New York City for 35 minutes.

The city, teetering on the edge of bankruptcy after years of unbalanced budgets, had come to a moment of reckoning, the Republican president said.

Washington would not come to the rescue, Ford said. City officials, he charged, were profligate spenders gripped by an “insidious disease.”

A bailout would set a terrible precedent, he said, and would impose unfair costs on the rest of the United States.

“The people of this country will not be stampeded,” Ford declared. “I can tell you — and tell you now — that I am prepared to veto any bill that has as its purpose a federal bailout of New York City to prevent a default.”

Ford’s address landed like a bomb in the city’s halls of power, then overseen by Mayor Abraham D. Beame, a clubhouse Democrat, and in Albany, where Hugh L. Carey, a liberal Democrat and Brooklynite, was governor.

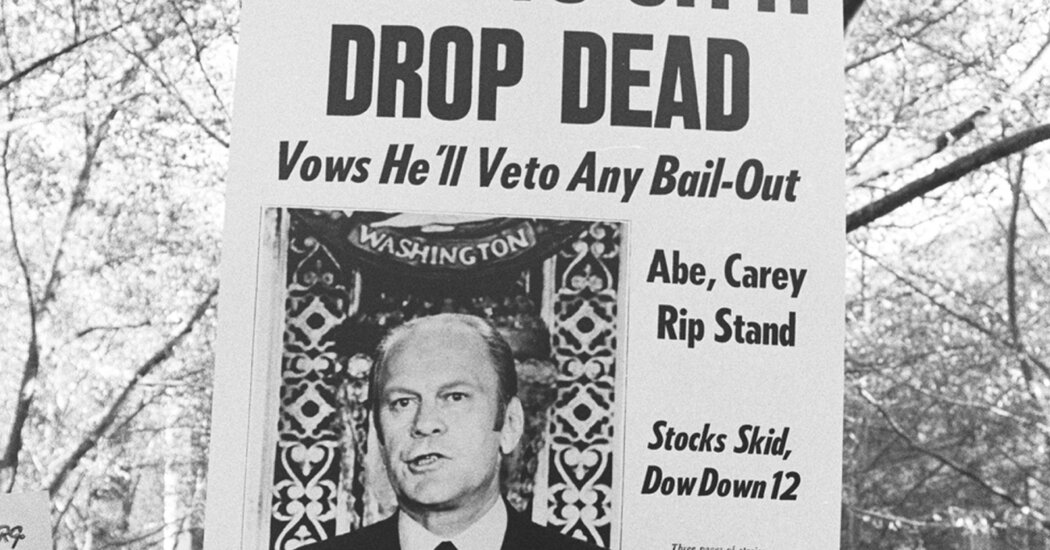

The next morning, copies of The Daily News arrived on doorsteps carrying a five-word headline in a towering boldface font. “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

Ford had never said those words. But the headline, which Ford would long argue was unfair, seemed to many New Yorkers to sum up the president’s callous indifference to the city’s future.

Two weeks earlier, New York had come within hours of declaring bankruptcy before being saved by its unions, with a last-minute investment commitment from the United Federation of Teachers. By the end of October, city officials were again running out of options.

“It was scary,” recalled Donna Shalala, who was a member of an entity called the Municipal Assistance Corporation that was created by the state in 1975 to allow the city to sell bonds.

But it did not take long for the president’s position to shift.

Within two months, he had authorized up to $2.3 billion in loans for the city. Still, voters narrowly delivered the state, and the presidency, to Jimmy Carter a year later. (The city repaid the loans with interest.)

Fifty years later, the clash between a Republican president and the city’s Democratic leadership seems newly resonant.

Today a different Republican president speaks of taking a hatchet to the city’s finances. President Trump has moved to cut off multibillion-dollar federal funding streams to New York and is threatening to go even further if Zohran Mamdani, the democratic socialist whom he has falsely called a communist, is elected mayor.

The Trump administration has already said it will withhold $18 billion in federal funds for a Second Avenue subway extension and new train tunnels beneath the Hudson River.

Cuts to programs that low-income New Yorkers rely on, such as Medicaid and food stamps, could put financial pressure on the city to step in.

And as Mr. Trump pursues a chaotic tariff policy that has roiled markets, economists have warned that the U.S. economy could tip into a recession. This month, JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s largest bank, put the odds of a recession by year’s end at 40 percent.

Some experts say the city is entering a period of profound budgetary risk.

The state comptroller, Thomas P. DiNapoli, a Democrat, has forecast that the city’s budget shortfall will be $13 billion by the 2028 fiscal year. “If this economy falters in any way or slows,” he said in an interview, the city could “really be in for some very challenging decisions on spending and taxation.”

Already, New York policymakers are dealing with long-brewing challenges. The state’s population of millionaires is growing at a rate slower than that of other large states, according to the Citizens Budget Commission, a fiscal watchdog group. At the same time, working-class and middle-class residents are fleeing the city, and the school system is shrinking.

Still, the city is a model of fiscal responsibility compared with the 1970s, largely because of guardrails created in response to the fiscal crisis.

Stephen Berger, who led the State Financial Control Board for part of the ’70s, said that bookkeeping in the Beame era had been shoddy and even nonexistent.

“When the city began ’75, it had already used and consumed all of its local tax revenue to pay off notes from the previous year,” Mr. Berger recalled. “And there were no real books that showed all of that.”

He remembered welfare records stuffed into cardboard boxes all over the city. Now, Mr. Berger said, there are “real budgets” and “real books.”

The city’s annual budget must be passed according to generally accepted accounting principles, which means that current expenses must be matched by current revenues. Since 1975, New York has also been overseen by the Financial Control Board, which meets annually and can impose restrictions on the city in times of budgetary turbulence.

And, in ways better and worse, the New York City of 1975 was a far different place from the New York City of 2025.

By the ’70s, the city’s tax base had been hollowed out by the erosion of industrial jobs and white flight to the suburbs. The subways were dangerous and coated by graffiti. City parks were filthy.

“Everyone had basically abandoned ship in New York,” said Michael Rohatyn, who directed a movie about the fiscal crisis. His father, Felix G. Rohatyn, led the Municipal Assistance Corporation for nearly two decades and is widely credited, along with the labor leader Victor Gotbaum, with playing key roles in saving the city from bankruptcy. In 1975, New York City was at its “gritty worst and at its glorious best,” Mr. Rohatyn added.

Now it is Black New Yorkers who are being pushed out. Housing supply is scant and costs are stratospheric. New parks and greenways are blooming across the city. And it is the flight of the ultrawealthy to Florida, along with their tax dollars, that keeps some policymakers up at night.

In 1975, New York City could not sell its municipal bonds. It has no trouble now. Mayor Eric Adams, a centrist Democrat who is due to soon leave office after a series of corruption scandals upended his re-election prospects, has often cited maintaining the city’s stable bond ratings despite the pandemic and the migrant crisis as among his chief accomplishments.

Bill de Blasio, the city’s mayor from 2014 to 2021, said in an interview that the city had gone from the “wounded bird of New York State” to the “engine of the state.”

But he added that he had kept 1975 in the back of his mind during budget season throughout his mayoralty.

“The fiscal crisis never died in our imagination,” said Mr. de Blasio, a progressive Democrat. “It should be part of our mythology in a good way.”

Today the financial health of the city is slipping somewhat, but from a strong position, said Gabe Diederich, a portfolio manager with the Baird Funds in Milwaukee who studies municipal assets. He described New York’s fiscal prognosis as mixed.

William Glasgall, a public finance adviser at the Volcker Alliance, a nonprofit think tank, said the city was approaching the next mayoralty in “pretty good shape” despite “real clouds coming from Washington.”

Still, some believe that as New York grapples with hostile federal officials, its fiscal health could turn on a dime.

“Things move very fast,” said Richard E. Farley, a New York lawyer who wrote a book about the 1975 crisis and expressed concern about obligations the city might undertake under Mr. Mamdani. “When the financial community loses faith in city leadership, it can turn with breathtaking speed.”

Andrew Rein, president of the Citizens Budget Commission, said New York had benefited from a stretch of years in which Wall Street boomed and federal money poured into the city under a Democratic administration.

The stock market is having another strong year. But if the economy falters as federal cuts hit, that could quickly put the city in a budgetary quagmire, experts say. In one respect, Mr. Rein argued, the city lacks a safety net it had in the 1970s: a state government on strong fiscal footing.

The state, which relies on the federal government for about a third of its funds, also has looming budget gaps; Mr. DiNapoli projects a state budget deficit of $34 billion by the 2029 fiscal year.

It is unclear how far Mr. Trump, a native New Yorker, might go to inflict fiscal pain on New York, and the city could fight any steep cuts in court.

But the president’s bellicose threats to Mr. Mamdani have made Ford’s lectures about fiscal responsibility seem tame. “He is going to have problems with Washington like no Mayor in the history of our once great City,” Mr. Trump wrote on social media in September. “Remember, he needs the money from me, as President, in order to fulfill all of his FAKE Communist promises. He won’t be getting any of it.”

The post New York Survived Its 1975 Crisis. Will Trump Push It Back to the Brink? appeared first on New York Times.