Maybe it is a function of my age—dad to a 20-something and a teenager who tend to view me as an unfortunate necessity—that I long for the early years of parenting. Oh, how I miss gnawing on fat wrists and elbows; getting tackled by a kid screeching “Daddy!” as I come through the front door; hearing the extended cut of a seven-year-old’s day, in lingering detail.

This is one of the reasons that I was so gutted on a recent trip to Lebanon and Syria, where—at the invitation of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR)—I found myself among Syrian refugees. At some point, the terrible things I heard from adult refugees started to blur: the substandard living conditions, the scarce job opportunities, and the fear of police raids. These Syrians now face a terrible choice of remaining in miserable conditions in Lebanon or taking their chances in Syria, which the U.N. security team in Damascus described as “unstable and volatile.”

The children are especially vulnerable. Their faces are etched into my mind. The deep dark eyes, the inquisitive looks, the furtive smiles. There were children playing in puddles by an abandoned school building, which now houses 41 families, north of Tripoli and near the Lebanese-Syrian border. One little boy in all blue with a modest push toy—the only toy I saw—plopped down in the water just in front of me. He giggled as I picked him up and handed him over to his burly dad.

Then there were the two little boys (one dressed improbably in green sweats that read “NY Jets”) and a baby sister, playing on the gravel pathway of an “informal tented settlement”—in the argot of international bureaucrats—near Zahle in the Bekaa Valley. Tented is a misnomer, given that the word evokes images of, well, tents. They were shelters of cast-off plywood, old UNHCR tarps, corrugated tin, and whatever else could be harvested from piles of garbage. For the privilege, their parents pay a private landlord $150 per month and an additional fee for trash collection, which never seemed to have taken place. Among displacement camps in the region, Zahle was the worst I’d seen—and not just me. A retired ambassador I traveled with, who had an extraordinary career in some of the toughest places in the Middle East, agreed.

This was all terrible on its face, but I ache for those little children because of something that I’ve learned over the years—war, politics, indifference, and hostility have fated them to a life spent on the margins, lacking dignity, vulnerable to violence and exploitation. In all likelihood, they will not escape the legacy of former Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s cruelties, the cynicism of the present moment in U.S. politics, and the exploitation by the Lebanese elite for either political or financial gain or both.

This is not a new discovery, of course. Journalists and humanitarian groups have documented the plight of Syrian refugees in Lebanon for some time. But it is one thing to read about it over coffee at my kitchen counter and another to be confronted with the cold reality of widespread suffering. I have been seized for days with ideas about how to help the kids I met, which mostly involves a fever dream in which I raid my local Target, buy up children’s winter clothing, stuff the goods into suitcases, and fly back to Lebanon. I know: Western savior syndrome is not a good look and, of course, it would be a drop in the ocean of need. Forgive me, I can’t stand to watch little kids suffer.

What makes it all worse is the deeply disturbing recognition that the United States has further immiserated these children. Through Washington’s extended political drama pitting globalists against MAGA, the U.S. foreign aid budget has been slashed so that people can beat their chests and own someone on X. The dreadful consequence has hamstrung UNHCR, which lacks the resources to make the schoolhouse in northern Lebanon structurally sound and provide babies with a winter suit. From where I stood near Tripoli and in the Bekaa Valley, the gleeful gutting of foreign assistance programs—based on the idea that previous administrations had been too generous—was absurd and small.

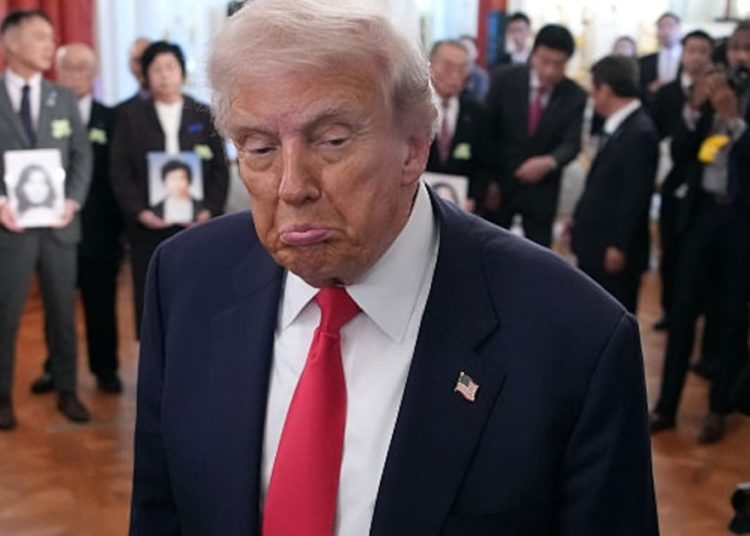

The real-world effects of DOGE bros and their fanatical expurgation of the foreign aid budget are devastating. In Lebanon—a country with few resources to spare—the government has prohibited UNHCR from registering refugees for a decade, which means they do not qualify for assistance. Medical care, mental health support, aid for people with disabilities, and employment are all scarce. There are refugee children who have never been to school. The Trump administration’s slash-and-burn approach to foreign assistance has made all of this worse. It is not hard to imagine kids who have no education, who are alienated, who are called “Syrian” but have never stepped foot in Syria, becoming angry and violent—a lost generation vulnerable to extremists, war lords, traffickers, and gangs. This is deeply unsettling. Chaos and instability are not inevitable, but by making it more difficult for governments, UNHCR, and its partner organization to mitigate some of the most pressing challenges that refugees confront, the Trump administration is increasing the chances of volatility and violence.

This is a very Washington think-tanker place to land. People in my circles love to argue that budget cuts in the United States lead to instability abroad. I am self-aware enough to recognize that I am approaching caricature here. But caricature doesn’t necessarily mean I’m wrong. Think of how disaffected, unemployed, or underemployed young men (primarily) become attracted to extremist groups that offer them a sense of identity, purpose, and mission. It is not hard to imagine how informal tented settlements can become hotbeds of radicalism.

In fairness, for all of the cuts, the United States remains UNHCR’s largest donor (shame on the self-righteous Europeans and Canadians). Washington’s contributions are a burden in part because others are not doing enough. But as far as burdens go, it is not a heavy one. What Americans gave to UNHCR before the cuts to foreign assistance and certainly what they give now amount to a small rounding error in the overall U.S. budget. And with it, we could ensure that little kids have winter jackets and that jerry-rigged shelters meet some basic minimum standard. Those modest steps should be well within the goals of even a pared-back foreign assistance budget.

True, those kids are not our kids, and we cannot save the world. But we can make the life of a toddler or a baby a little less precarious.

The post For Syrian Refugees, U.S. Aid Cuts Have Been Devastating appeared first on Foreign Policy.