My 10-year-old daughter’s entry into the universe of Labubu was innocent enough: She was a kid who wanted a doll.

So how did my usually thoughtful and steady 10-year-old wind up in tears in the middle of a bleeping, blooping tween arcade full of claw machines in downtown Montreal? This is, in part, a story about getting stuck in the false promise of a rampant trend cycle — in this case, one involving ugly monster dolls. It’s also a story about how my daughter and I found our a way out again.

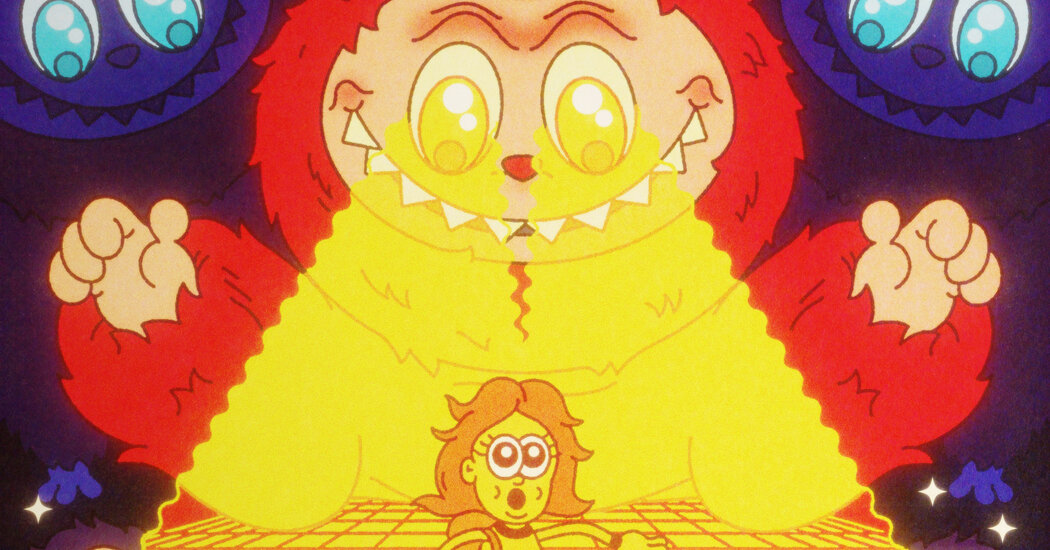

Labubu dolls — which look like a cross between a Maurice Sendak “Where the Wild Things Are” monster and a Monchhichi — became extremely trendy a year ago when a Labubu was seen dangling from the handbag of Lalisa Manobal, who goes by Lisa, of the South Korean pop group Blackpink.

Après Lalisa, la delulu: Labubus popped up among celebrities and style influencers, ornamenting the bags of everyone from Rihanna and Dua Lipa to the soccer legend David Beckham and the tennis champion Naomi Osaka. By last summer, Labubus had gone from being a weird totem of adult fashion juvenilia — a junky-looking fuzzy toy hanging, almost as counterpoint, from $100,000 Birkin bags or the sports totes of millionaire athletes — to a mainstream object of intense juvenile desire. Labubus, like Cabbage Patch Kid dolls, Tamagotchis or Beanie Babies before them, became the thing kids wanted simply because all kids wanted it.

Naïvely, I thought I’d sidestepped the whole mishegas when a family member took my daughter out for dinner in Montreal’s Chinatown and bought her, for $10, a knockoff Labubu — what the kids refer to as Lafufus. She named her doll Tyler Janeiro (after her most recent musical hero Tyler, the Creator and her favorite body spray, Sol de Janeiro) and sewed small, ingenious clothes for it out of scraps of fabric. She excavated accessories for Tyler Janeiro from her toy bin, culling odds and ends from her American Girl doll and Calico Critters collections left over from other toy phases she’d recently outgrown.

I was initially fine with this temporary phenomenon because I thought Labubus were, in the end, merely a toy: something that a child — even one who is growing up quickly — could play with. Like many parents of Gen Alpha kids, I’m both astounded and terrified by the amount of time my child wants to spend on online shopping sites like Temu or Shein. So I liked that Labubus, like the Furbys or Tickle Me Elmos of yore, were difficult to acquire. You couldn’t just order one with the click of a button. You had to strategize, or at least to wait.

If social media is the main outlet for mindless scrolling and bed rot for millennials and Gen Z-ers, then for members of Gen Alpha, like my daughter, the preferred rush seems to be online shopping. The ability to think of something — a miniature snow cone maker, a water bottle shaped like a penguin, magnetic socks that can hold hands — and then actually find it online in a minute, with the option to click once and procure it, seems like catnip to certain kids’ brains. (And adult brains, too. Believe me, I have known plenty of midnight marathons on the RealReal website). The Labubu represented a rare example of delayed gratification for my daughter, and, in that way, felt to me comfortingly safe and retro.

Then came a week of day camp in July.

My daughter headed off with Tyler Janeiro affixed happily to her backpack. She returned home that afternoon to report that she was removing Tyler from her bag. She’d believed that real Labubus were impossible to find, she explained, but a camp counselor, who I will here call Chad because Chad is a name I don’t like, told her that there was one place in Montreal where you could, in fact, get real Labubus. Chad, in fact, had three. It was easy, according to Chad. She’d just need to win one or, more specifically, to catch it with a claw, in a claw machine, at a claw-machine arcade downtown.

In Montreal, claw-machine arcades are a fairly new addition to the universe of places that are irresistible to children and triggering to the migraine syndromes of their middle-aged moms. Like the dreaded pop-up Halloween shop, claw machine arcades tend to colonize spaces vacated by bankrupted stores undone by the rise of online shopping, remote work and the general upheaval of the once-useful physical world. Where, for three generations there stood, say, a family-owned department store that could service an entire life cycle of needs, from baby layettes to orthopedic shoes, there now stands an LED-lit, dopamine-harvesting arcade, equipped with machines designed to turn our youngest consumers into rabid, saucer-eyed addicts.

Our specific destination was one of the more upscale claw arcades in downtown Montreal. Inside, Plexiglas boxes, into which a thick stack of tokens must be fed for the chance to grasp prizes from the machine’s shallow pile, vastly outnumbered the traditional video games and pinball machines. With the claw machine, one’s tool is a loose, slippery appendage powered by a joystick, with a three-fingered pincer at the end that in any other context would be deemed defective. All but the cheapest of prizes are nearly impossible to catch — but just one toy rubber ball grabbed at the first try will convince a child that more bounty is sure to come. Claw machine arcades are like Vegas for kids — casinos with training wheels.

I did not realize this before we arrived. I thought instead that my daughter and I would spend some quality time together. Since she’d hit 10, and began adorning her room with Kendrick Lamar posters and striped bags from Sephora, it had been harder for me to reach her. She’d started saying, “Personal space, Mama!” whenever I went in for a kiss, a situation that made me feel like my uterus was crying.

A girls’ afternoon out, I thought, was just what we needed: We’d go to this arcade, get the coveted Labubu, then go for pizza nearby. I envisioned me and my kid giggling and holding hands. I’d kiss the top of her head and she would not flinch.

Inside the claw arcade were three machines in which the prizes were genuine Labubus. A large, multigeneration family in front of us already had two Labubu boxes in their basket. “Look, they’ve already won twice!” clapped my daughter, eager to get started.

I’d bought $20 in tokens — and within five minutes we’d failed four times to claw a Labubu. So I bought $20 more, and failed again. The nearby family began to help us, jiggling the machine this way and that, while my daughter maneuvered the joystick with more and more gumption. I bought still more tokens, my daughter feeding them into the slot faster and faster, and by the time we were done, I’d spent $90, we had no Labubu and my daughter, usually so composed in her newly acquired preteen armor, dissolved into tears.

“I can’t believe it!” she cried. “We didn’t get any!”

The dad from the other family stood next to us, watching with understanding eyes, which I now noticed were also exhausted eyes.

“You should know we’ve been here for three hours,” he said. “I’ve spent $500.”

We did not win a Labubu. My daughter was inconsolable the entire evening. The following morning, she sat down on our sofa, rubbing her eyes, almost looking hung over.

“I don’t even know what happened yesterday,” she said, dazed. “I feel like I was crazy.”

I told her that I’d also felt completely beside myself, and that she was definitely not crazy. We’d been played.

“By what?” she asked.

And I thought: By a culture that offers us consumption when we need meaning? By the desecration of creativity through commerce? By the fact that the online world has infected us with an insatiable need for more and more instantly attainable stuff and a heedless rush of desire that can never be satisfied?

But all I said was: “There’s a lot around now that makes people constantly think they want things. Those claw places are designed to make kids addicted, and they are bad places.”

My daughter nodded. “Definitely bad places.”

I sat with my mom guilt. I was the one who drove her to that place. I was the one who kept opening my purse, rather than modeling restraint. It was as though her desire to get the doll and my desire to make my daughter happy had collided in a conflagration of misguided intentions. But this misadventure did ultimately result in an unforgettable, and thus effective, teachable moment for both of us: Together, we’d come face to face with pernicious consumerism, stripped of any seductions, in all its flagrant emptiness.

That said, she did get a Labubu.

As we were leaving the claw arcade the night before, we’d learned that, at the exit, you could buy a genuine Labubu straight-up for $85. By that point, my daughter understood that, having already pumped 90 bucks into the claw machines, there was no way I could spend any more money on Labubus.

So the next day she got to work.

She sold lemonade on the street. She saved her allowance. She sorted and rolled coins from her piggy bank. She made a business of giving two-dollar massages to a clientele of one (me). Finally, she told me that she had enough money and would need to return to the claw arcade.

My daughter carried her new, genuine doll, the strangely named Big Into Energy Labubu, in a transparent purse like a portable display cabinet for the rest of the summer. After she bought the doll, I asked her to keep a Labubu diary for a couple of weeks, noting how she felt about it. I wanted her to see how fads work: how you think the thing will change your life but, not much later, it’s become just a piece of plastic clutter.

She brought the doll to school for the first day. When she came home, I asked her whether her friends were interested in her Labubu.

“Not really,” she said, a little haughtily. “They got Labubus, too.”

Then she asked me what was for dinner. I told her roast chicken and carrot soup.

It was then that I knew our family’s summer of monster doll desire, our Labubu clawpocalypse, was finally over. We were scarred, yes, but we were smarter, too, and now we were free.

“I don’t know why you are still talking so much about Labubus, Mama,” she said as she set the table, pulling out the place mats like a big girl, without my even asking her to. “They are really not that big a deal.”

Mireille Silcoff is an author and a cultural critic who lives in Montreal.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post Rescuing My Daughter From the Cult of Labubu appeared first on New York Times.