Americans who want to bet on sports have many options. There’s DraftKings, FanDuel, ESPN Bet, Caesars, and BetMGM. There’s also BetRivers, Hard Rock, bet365, Fanatics, and Bally Bet. But none of those platforms are available in the 17 states where online sports betting remains illegal, including California and Texas.

Kalshi, a prediction market, doesn’t have that limitation. Gamblers can use it to wager on the outcome of sporting events in all 50 states. That’s because, in the eyes of American law, Kalshi is not a gambling company at all; it’s an exchange that facilitates the trading of legitimate financial products. Over the past year, the company has added sports to the range of events that can be wagered on, while arguing that it is beyond the reach of any state-level gambling ban. It maintains that it can be regulated only by the federal Commodity Futures Trading Commission. But under the second Trump administration, the CFTC has shown no interest in cracking down. The result is that sports betting is now legal everywhere—even in the states where it isn’t.

Futures contracts have been around in the United States since the late 1800s. Midwestern farmers planted and harvested grain at roughly the same time every year, and then everyone went to Chicago to sell. This sudden abundance of grain would cause prices to plummet. Middlemen swooped in to help. They’d buy the grain and store it nearby, selling it for a profit in the winter. This helped to stabilize prices, but some buyers wanted more certainty: a set amount of grain at a set price at a set date, so they could plan ahead. Middlemen obliged, writing contracts for the future delivery of grain.

Soon after, people began trading the contracts. A bakery might buy a grain contract from a distillery. Farmers could buy the contracts, too, to hedge their bets: A Michigan farmer might buy a grain contract from a Wisconsin farmer, so that if Michigan had a bad harvest, he’d still have some grain to sell. Speculators joined the party. If the cereal market was growing, a savvy market-watcher might notice, scooping up grain contracts that would be worth more later. That serves a useful economic function. Without these middlemen, the price of grain might stay artificially low for a long time, and then spike once everyone notices the growth. The speculator provides liquidity and, with it, stability.

At some level, the speculator is gambling. “All you’re doing is betting on whether the price of grain will go up or down,” Karl Lockhart, a law professor who studies prediction markets, told me. As futures markets matured, states tried to step in, and politicians introduced anti-options bills. The federal government, however, intervened repeatedly to save the nascent industry. “It seems to us an extraordinary and unlikely proposition that the dealings which give its character to the great market for future sales in this country are to be regarded as mere wagers,” Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote in a 1905 decision.

With the government’s blessing, the futures market continued to evolve. People began trading currency futures in the ’70s, betting on the fluctuations of the pound or the franc or the Mongolian tugrik. Soon after, markets were created allowing banks to buy and sell bets on future interest rates. The banks were hedging, much like the hypothetical Michigan farmer—if interest rates went up, they’d be hurt, so they would bet on interest rates going up, and then their losses wouldn’t be so big. Other financial firms would take the other side of the bet. Were they gambling? Maybe, but they were also helping banks stay solvent.

Hedging opportunities are everywhere, and they don’t always require a contract to buy or sell an underlying asset. In what’s known as an event contract, a company might bet on a specific adverse development, such as its competitors merging. Kalshi, founded in 2018, specializes in event contracts, a category that it interprets very broadly. (The word kalshi means “everything” in Arabic.) When Tarek Mansour, the company’s CEO and one of its co-founders, was interning at Goldman Sachs in 2016, he told me, clients would ask the bank to design a way to hedge against Brexit or a Donald Trump presidency. (Imagine you run a company that makes offshore wind turbines, Trump’s least favorite thing in the world. If you had bet on a Trump victory last year, you’d be in better financial shape now.) Political betting was technically illegal, though the government tolerated it in small amounts, on sites run by academics and nonprofits for research purposes. Then, in 2023, Kalshi declared its intention to introduce political markets in which users could bet on which party would control Congress.

The Biden-era CFTC decided Kalshi’s political expansion was prohibited because it involved “gaming and activity that is unlawful under state law” and was “contrary to the public interest.” Kalshi challenged the CFTC’s order in federal court. The judge ruled in Kalshi’s favor, reasoning that if betting on elections were to count as gambling, then so would betting on the weather, or a merger, or an earnings report, or interest rates. At issue, fundamentally, was where the line between gambling and investing really lies.

The Biden CFTC appealed the court’s ruling. Kalshi, in its response to the appeal, tried to make the boundary between futures trades and gambling clearer. (After Trump took office, the CFTC would drop the appeal.) A bet is gambling only “if it is contingent on a game or a game-related event,” Kalshi’s lawyers at Milbank and Jones Day argued in a filing last November. “The classic example is a contract on the outcome of a sporting event.” Political betting isn’t gambling, the argument went. Sports betting is gambling—and that’s not what Kalshi was offering its customers.

Less than three months later, Kalshi announced that customers could bet on the Super Bowl. When I asked about this discrepancy, Mansour told me that the legal filing had been written by “outside counsel” and that what it expressed was “not our view.” Today, Kalshi is mostly a sports-betting company, but one whose users can live anywhere and need to be at least 18 years old, rather than the typical 21. Since football season started, early last month, sports betting has accounted for more than 90 percent of the activity on the platform. A freshly signed licensing deal with the NHL allows Kalshi to use team logos and names instead of soliciting bets on “New York J at Cincinnati,” as it still does for football.

Kalshi users can wager on more than just the outcome of a game. A football bettor, for example, could bet on the margin of victory, how many passing yards one of the quarterbacks will have, or how many rushing yards one of the running backs will have. They could even combine these three bets into a parlay, where the odds of winning are lower, but the payout for winning is higher. Kalshi calls this a “combo,” perhaps to avoid using the no-no gambling term parlay.

The day after Kalshi rolled out its combos, the stock prices of DraftKings and FanDuel’s parent company each fell more than 10 percent. Kalshi knows that investors and customers think of it as a gambling company; in fact, its advertising encourages them to. One Kalshi social-media ad announces “BREAKING NEWS: SPORTS BETTING IN TEXAS IN NOW LEGAL” and that “Kalshi has legalized sports betting in all 50 states.” (When I asked Mansour about this kind of advertising, he said, “The minute we basically saw them, we basically took them down.” This type of ad was first spotted in February, and Kalshi re-upped them as recently as last month.)

Kalshi insists that it is not a sportsbook, but rather an exchange that matches buyers and sellers of legitimate event contracts. Some of the events just happen to be sports, rather than mergers. A sportsbook makes money when you lose, which puts its incentives directly at odds with the interests of the user. Kalshi, by contrast, makes its money from fees.

Even setting aside the formalism of the distinction, this argument is undermined by the fact that a subsidiary, Kalshi Trading, does take bets against customers. So does a partner, Susquehanna International Group, which provides a “market making” service for Kalshi by being on the other side of users’ bets. The same goes for Kalshi’s army of decentralized market makers who are compensated in return for providing “liquidity” to the market. All of these entities make money when ordinary users lose their bets.

Tim Ford is a sports bettor on Kalshi. He uses an algorithm to determine probabilities for game outcomes, then buys or sells contracts that deviate from those probabilities. He has made more than $100,000 over the past month this way, according to Kalshi’s public leaderboard. (His handle is CSPTRADINGonX.) Ford, who lives in Texas, doesn’t defend the morality of Kalshi’s end run around the state’s gambling laws. But without the company, he would be significantly poorer. “At the end of the day, they are certainly effective,” he told me. Kalshi facilitates more than $900 million in bets a week, keeping a steep percentage in fees (more than 5 percent for a $20 bet). Earlier this month, it announced that it had raised more than $300 million at a $5 billion valuation; now investors are trying to get in at a $10 to $12 billion valuation. The personal-investing platform Robinhood has embedded Kalshi’s prediction markets into its savings app.

Kalshi’s rise has not been without controversy. Last November, FBI agents raided the home of the CEO of Polymarket, Kalshi’s biggest competitor. Polymarket, a crypto-based prediction market, was being investigated for allegedly allowing Americans to use its platform in violation of a settlement with the CFTC. (In July, the company said that the probe had been dropped, and the CFTC has since declared that it can legally operate.) Following the raid, two white Kalshi employees persuaded the retired NFL player Antonio Brown to tweet “this nigga seem guilty.” (“This was a mistake,” Mansour told me.)

If Kalshi’s marketing can be disorganized, its legal strategy is not. To help navigate the regulatory environment, Kalshi employs Donald Trump Jr. as a strategic adviser, and has hired as its lawyer the Democratic superstar Neal Katyal, who has argued in front of the Supreme Court more than 50 times. The company argues that it’s not subject to state gambling bans, because they are preempted by the presence of federal law regulating futures contracts.

That argument is being tested in court. In response to cease and desist letters, Kalshi sued Nevada, New Jersey, and Maryland in the spring, asking courts to prevent the states from cracking down on them. According to Andrew Kim, a lawyer who has been tracking the litigation, the company has since added Ohio to the list and has been sued by the state of Massachusetts, three Indian tribes in California as well as one in Wisconsin, and private plaintiffs in seven states. In at least two instances, Kalshi has won preliminary injunctions to allow it to keep operating while the cases proceed.

If states can’t stop so-called prediction markets from facilitating sports betting, who can? According to Kalshi, no one besides the CFTC (or, in theory, Congress). The company classifies the transactions on its platform not as wagers but as “swaps,” which the post–Great Recession Dodd-Frank financial reform law charges the CFTC with regulating. To qualify as a swap under the law, the event being bet on must be of “potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence.”

This requirement has led Kalshi to interesting places. Super Bowl bets must be swaps, Kalshi’s lawyers argue, because the winning team generates additional revenue. Whether a player scores a touchdown in a particular game, Mansour told me, has economic consequences for the player’s sponsorship deal. Even parlays have economic consequences, Mansour explained, because sportsbooks offer parlays and could use Kalshi to hedge by taking the other side of the bet.

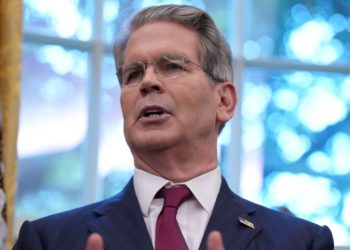

If Kalshi’s bets are swaps, then regulating them is the CFTC’s job and no one else’s. This is very convenient for Kalshi. Four of the five CFTC commissioners have resigned since January, and the last one remaining on the commission, which is bipartisan by law, is a Republican who announced she’d leave as soon as Trump’s pick for chair, Brian Quintenz, was confirmed. Quintenz, a former CFTC commissioner, is on the board of Kalshi.

On September 30, the eve of the government shutdown, there was finally some action. Six senators posted an open letter to the acting chair of the CFTC asking her to stop allowing sports-prediction markets. Trump pulled his nomination of Quintenz after the Winklevoss brothers told him that Quintenz would be too hard on crypto. And CFTC staff issued their first guidance on sports-prediction markets. In a letter to all approved exchanges, they wrote that they “are aware that certain registered entities and registrants are listing or facilitating the trading or clearing of sports-related event contracts, or may be interested in the future in doing so.” Their advice? “State regulatory actions and pending and potential litigation, including enforcement actions, should be accounted for with appropriate contingency planning, disclosures, and risk management policies and procedures.” The letter perfectly closed the buck-passing loop. States had tried to regulate sports-prediction markets. The courts had suggested that responsibility belongs to the federal government. Now the federal government was telling the sports-prediction markets to beware of the states and the courts.

For now, the industry, its investors, and its gamblers are in limbo. If they’d like to hedge, Polymarket is taking bets on whether the Supreme Court will accept a case on sports-event contracts by July 2026.

The post The Loophole Making Sports Betting Legal Everywhere appeared first on The Atlantic.