After having lunch last week with President Trump in the White House, exchanging gifts and praise and securing billion dollar commitments from the United States, President Javier Milei of Argentina returned home to his voters.

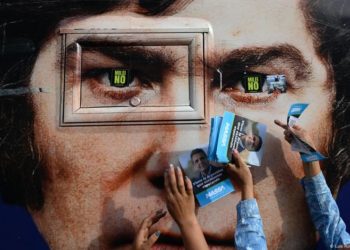

Wearing a leather jacket and holding a megaphone on the back of a pickup truck, Mr. Milei, a self-described anarcho-capitalist economist and former firebrand pundit, rode through crowds of students, farmers and pensioners. He pleaded with them to support him in a pivotal midterm legislative election on Sunday — his toughest test yet.

“I’m asking you to stand with us,” Mr. Milei told an audience wearing Lionel Messi soccer jerseys and red MAGA caps on Tuesday in Córdoba, the country’s second-largest city. “We’re at a turning point in Argentina’s history.”

The election has gained outsize attention after Mr. Trump endorsed Mr. Milei, a like-minded ally, and warned that a $20 billion lifeline he has promised to Argentina depends on the vote’s outcome.

It is also seen by economists and the financial markets as a test of Mr. Milei’s bold experiment to try to jump-start a chronically unstable economy.

Yet for all of the high-stakes international attention on the election, the final verdict belongs to Argentine voters, who have the first chance to grade Mr. Milei since he was elected president in 2023.

Mr. Milei needs a strong showing in the midterms to gain enough support in Congress to pursue his agenda, but how well his party will perform remains uncertain. Around the country, optimism about Mr. Milei’s cost-cutting program and relief over Argentina’s slowing inflation has mixed with fatigue from the austerity measures, stalling growth, job losses and corruption scandals.

Even in the central province of Córdoba, a conservative stronghold, Mr. Milei’s electoral success now seems in doubt.

On the street where Mr. Milei held his rally, shopkeepers have closed stores as sales plunged. Retirees say they can no longer afford their medications, doctors and university professors have held strikes to protest decreased funding, and factory workers gather outside shuttered plants.

“We voted for him and now I am sitting here with no work and no money,” said Diego Gómez, 43, a chemical-plant worker who said he was laid off this year in Río Tercero, a town in Córdoba Province.

Sitting on plastic chairs and drinking mate outside the chemical factory, several workers said they had trusted Mr. Milei’s vow to take a chain saw to Argentina’s sclerotic and often corrupt political establishment, which has overseen decades of economic turmoil. But recent bribery scandals involving some of the president’s closest allies have left them believing that Mr. Milei was not actually crushing the elite.

“He blew up the working class,” Mr. Gómez said.

Mr. Milei is pleading with voters to be patient, promising that his economic project will eventually pay off, particularly now that the United States is offering assistance. The United States has pledged to provide Argentina a $20 billion currency swap and American investors are weighing whether to lend an additional $20 billion.

But after securing such a generous package from the world’s richest country, earning his voters’ patience seems an even higher hurdle for Mr. Milei.

“I know you don’t make a generational change in a year,” said Darío Maldonado, who also lost his job at the chemical plant and voted for Mr. Milei in 2023. “If everything wasn’t so bad, if everything wasn’t so dire, I would give him more time.”

A few dozen miles of dirt roads south of Río Tercero, where giant lizards strolled, pensioners walked to a community center in Villa María for free medical checkups. Most pensioners in the town receive the equivalent of about $250 dollars a month, which is around the national poverty line.

Life was never easy for them, but they said Mr. Milei made things worse by failing to increase pensions as drug and other prices soared.

“I am very worried about food,” said Graciela Ñañez, 64, a pensioner who said she struggles to give her grandchildren yogurt or rent clothes for their school graduations.

Ms. Ñañez said she had voted for Mr. Milei. “I was angry,” she said. “I don’t understand much about politics, but I saw the misery in Argentina, I saw the poor who kept getting poorer and the rich who kept getting richer and I thought it was the old government’s fault.”

“But,” she added, “now people are disillusioned again. They are desperate.”

José Rubén Torres, 72, another pensioner, said he used to buy tickets to watch his local soccer team, the Alumni. But these days, unable to afford tickets, he stands on the sidewalk outside the stadium, trying to catch glimpses of games from behind a fence.

Mr. Milei’s efforts to reduce inflation, from an annual rate of 160 percent when he took office to around 30 percent now, has helped decrease the poverty rate by 10 percentage points, to 32 percent.

But experts say the middle class has borne the brunt of his austerity program with sharp increases in utility bills, school fees and health care costs, forcing many households to scale back their spending.

Mr. Milei held his rally Tuesday in downtown Córdoba among rows of clothing stores largely empty of customers. Pablo Heredia, 44, who owns a chain of men’s clothing stores, said he had closed one branch and was likely to shut another as sales plummeted.

“We were used to going out to dinner, going on holiday, now I straight up don’t have any money,” Mr. Heredia said.

Sales had also plunged in a store selling baby gear across the street. But the 25-year-old shopkeeper, Milena Torres, said her support for Mr. Milei had not waned. “Things are very tough, but I believe and hope that things will be better in the future,” she said.

That is a sentiment Mr. Milei is hoping many other voters embrace. “I never said it was going to be easy,” he shouted into a megaphone amid a crush of people elbowing to shake his hand on Tuesday.

Mr. Milei has argued that his economic overhaul, including reducing the size of the government, budget cuts and deregulation measures, is laying the groundwork for new investment and future prosperity once Argentina regains credibility with global markets after decades of high spending, defaults and bailouts.

Many Argentines say they still trust him to fulfill his promises.

“I want to keep trying,” said José Luis Acevedo, a real estate developer, as he sat by the pool of an apartment complex he was building in Córdoba. He said his business was operating at a loss, but he was prepared to weather the challenges for a more stable financial climate that could sustain a mortgage market — which is virtually nonexistent in Argentina.

“I’d rather endure a few years of difficulty,” he said, “with the hope and the goal of reaching a time when our currency is sound.”

Inflation has plagued Argentina on and off for decades, and its effects were visible around Córdoba.

The farmlands around the city were dotted with 200-foot-long plastic tubes where many farmers stored their harvest because they regarded their crops a safer financial deposit than keeping pesos, the local currency, in bank accounts.

“I don’t want to go back to what we had before,” said Rafael Cueto, 53, a soy farmer.

For many, going back meant predicting what shoe size children were going to be and buying them before prices roses, or stocking up on gallons of milk. Moira Minue, a Milei supporter at his rally, said she could now buy toys on Amazon after the president lifted some import restrictions.

Nearby, José Orta, held an Argentine flag, but it included the words “No colony,” a reference to criticism among some Argentines that Mr. Milei was selling out Argentina’s sovereignty to the United States in exchange for financial support.

Some of the president’s supporters did not think that was a bad idea.

“We want to be a capitalist, right-wing country,” Rosa Ortelli, a teacher who works with the blind, said at Mr. Milei’s rally on Tuesday. “And if the United States wants to buy us, that’s great.”

Emma Bubola is a Times reporter based in Rome.

The post Trump Is All In on Milei. What About Argentines? appeared first on New York Times.