Anish Kapoor is one of the world’s most celebrated and popular artists. Over the years, he has won Britain’s Turner Prize, a knighthood and an honorary doctorate from Oxford University. In 2006, on the lakefront in Chicago, his stainless-steel “Cloud Gate,” a.k.a. The Bean, became early selfie-bait: The sculpture is like the legume of its nickname — if that were enlarged to the size of a tractor-trailer and polished to a mirror finish. Other Bean-ish sculptures have gone on to be built, for millions of dollars, in fancy spots around the world.

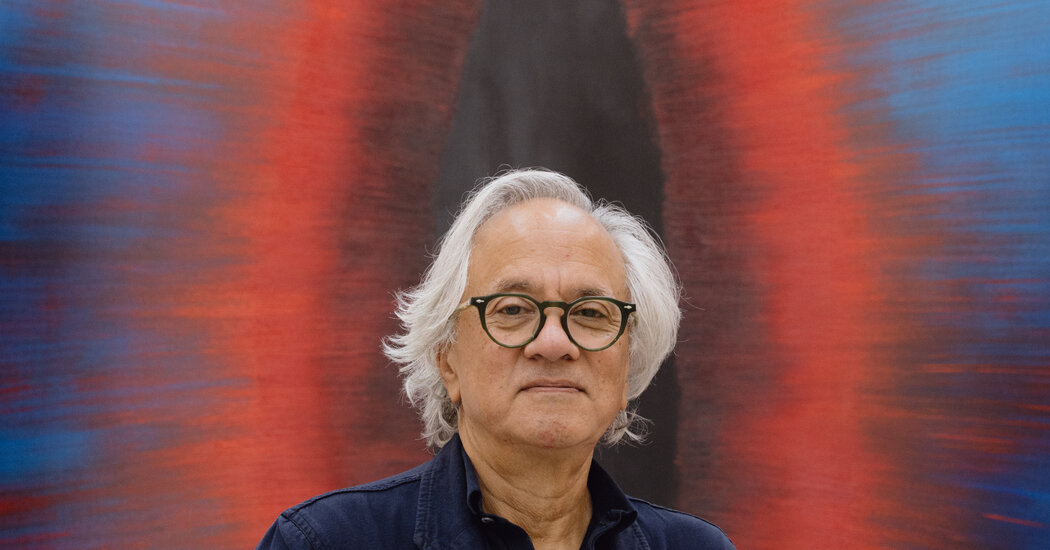

But right now, Kapoor, 71, is preparing to open a show that returns him to a much different era, in the late 1970s and early ’80s in London, when he was still the classic starving artist. “Anish Kapoor: Early Works” is opening Oct. 24 at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan.

The show presents the first sculptures Kapoor coated with powdered pigments, or set down among drifting piles of the stuff. They earned him a dose of art-world love. When he used the same powders to line half spheres, the critic Michael Brenson in The New York Times described the result as “the kind of magical, disconcerting sculpture that undoes vision and logic.” (The Jewish Museum will pair his early works with a few recent pieces that use Vantablack, a light-absorbing coating; Kapoor has the exclusive right to use it in works of art.)

Kapoor was born and raised in Mumbai, and since the 1970s has lived and worked in London, and lately, also in a grand palazzo in Venice.

In early September, on a video call from his studio in Venice, I spoke with Kapoor about his earliest art, and his very latest.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Blake Gopnik: At the Jewish Museum, you’re having a show of your early work. But — and I wasn’t ready for this when I started thinking about this interview — you’ve just now revealed one of the most powerful works of your career, and the most political. And that’s a guerrilla collaboration with Greenpeace that saw a giant canvas hoisted onto an oil rig and then drenched in red paint like a giant bloodstain, as though global warming was wounding the planet. Does that very latest work change how it feels to look backward, in the Jewish Museum show, to where your art started? Does it change how we should read that early work?

Anish Kapoor: No. I think art that simply comes to dictate to the viewer how it ought to be looked at is just not very good art. I’m afraid we have too much of that stuff around nowadays, and I’m a great believer in the other place, which is: How does one hold to metaphoric language?

But does that mean that the Greenpeace work, with its direct message and meaning, isn’t really an Anish Kapoor?

It absolutely is. It absolutely is. I hope — forgive me if I’m a bit arrogant about it — and think it’s quite a good work, as a thing in itself. And then of course, because of the association with Greenpeace and because of the really important issues of global warming, it has a particular reading in this context. I’m carefully considering whether I should show it again in a different context and see if that’s possible. I like the performative nature, if you like, of making a painting out there, out there in the North Sea, in the big space of the ocean.

Let’s go back to a moment in the 1970s and early 1980s London. Those first works with loose pigment [in the Jewish Museum show] were what brought you recognition. Is there some pleasure in revisiting those works from before you were known, before you were in demand, before you had giant budgets — and reporters calling you for interviews?

Definitely. When I first started making pigment works, I didn’t have any money. After I left art school, I was teaching one day a week in the north of England, in an art school. It was hardly enough money to pay the train fare, there and back.

In those days, in London, I paid five pounds a week for a studio — but to buy pigment? Oh my God, it was difficult. So I would often sweep the floor and use the dust off the floor. It’s just what I had to do. So there was this sense for me, anyway, of the frugal nature of the project.

Can you describe the breakthrough moment when you discovered loose pigment?

I’d been in England for five, six years — very, very difficult years. I’d been to art school, and was getting myself a little studio. And then the opportunity arose to go back to India, with my parents. My father directed the ocean hydrographic survey, which had its headquarters in Monaco. So they lived in the south of France. And we went to India, and I suddenly saw this material, in the market, as one does in India. And it occurred to me that it was a possibility. After two weeks, or whatever it was, in India, I came back to London, went to the studio and made my first pigment works.

And had you ever witnessed Holi, the festival where pigment gets thrown?

I was in India until I was 16 years old, so I’d grown up with it. But it’s not Holi so much that was the question; it was the pigment used in worship. Red pigment — or saffron pigment, more than red — would be used to anoint. You go into the temple, and you anoint the image with it, and in return, it’s put on your forehead.

One of the things that I love about your early works is their ephemerality, their fragility, which a lot of your later works, like “Cloud Gate,” don’t have. You have said, “Pigment is very fragile, to touch is to destroy.” Did you have a special pleasure in that fragility at the time?

Absolutely, absolutely. Also the way that they have a kind of aura — how the pigment spreads [around the sculptures] on the floor. And the ritual performance of laying it out: There’s a lot of housework involved in trying to make sure the pigment doesn’t go everywhere. But yes, the fragility is absolutely intrinsic.

My recent Vantablack works are so fragile that you can’t even breathe on them. Sadly, I’ve had to hide them away in a case, which I don’t like doing. I’d like to leave them open. So fragility plays a role there.

Did you ever take pleasure in watching the pigment get spread through a gallery and onto people’s clothes when they touched it?

I never enjoyed it. I always find it damned irritating, because I’m looking for that aesthetic purity, a kind of clarity — so that the object has its own particular particularness.

But a collector once said to me, “You know, now my children are Jewish and bluish.”

Often your work is seen as almost cheerful. But it seems that with Vantablack, you’re getting back to Edmund Burke’s idea of the terrifying sublime.

Terror is absolutely important, absolutely vital. The aesthetic proposition needs always, I believe, to sit on that edge where psychic and physical disappearance is almost palpable.

The Greenpeace work is huge, it’s almost nature scaled. Does that feel like one of those pieces where the terror of the sublime is there?

Yes, yes. The whole idea of trying to do this in the middle of the ocean, and holding on to the scale — the fear always was that in that vast space, the endless North Sea, it would be an insignificant object, but actually it somehow held the scale, which I’m really surprised at, frankly.

Now I want to change the subject completely. Your art connections to India — your Hindu roots — those are cited all the time. And you mentioned recently that it was important for a person of color to have succeeded as much as you have, given the racism you’ve experienced. So your Indian background is what’s always cited.

But here you are showing in the Jewish Museum, and I think some viewers would be surprised to know that you have an equally substantial background in Jewish culture, because your mother is Jewish, from Iraq, and her father was a cantor at an Indian synagogue. Did an interest in those roots, the ones that are less often cited, have anything to do with your accepting to do the show at the Jewish Museum?

My Jewish origins are absolutely part of my reality. Therefore it felt natural. I don’t know what else I can say.

Let me go back to the work. There are certain concepts that have remained absolutely essential for me, one of them is this wonderful word, “makom,” in Hebrew, meaning place. Now, art doesn’t just happen anywhere; a great work or a good work or a significant work, sites for itself a place.

As it happens, “makom” in kabbalah is also a word for God. So therefore this association of place and the infinite — meaning the here and the not here — these concepts are essential to what I feel I’ve been engaging with as an artist, almost from the very beginning. The Indian tradition holds many of these concepts too, but has more reachable visual languages. Our Jewish tradition has these conceptual, metaphoric, metaphysical realities that are just as important and for me, just as real.

You have said, “I have zero interest in being an Indian artist.”

Yet you’ve also cited the importance to you of India, and now of your Jewishness. Where do you stand on the issue of ethnic identity? It feels as though it’s been vexed for you over the years.

It seems to be a modern reality that so many of us are in transition, or in between. Home is a very difficult concept for me. I’ve always found it difficult. We live, my wife and I, between Venice and London. And we’re always on the move. This is the only place I belong — here in the studio. I don’t belong anywhere else. I say that, you know, almost with tears in my eyes. I mean, I wish I did, but I don’t.

The post Anish Kapoor Isn’t Done Reflecting appeared first on New York Times.