On a mild spring night in Chicago, a woman told her 18-year-old boyfriend she wanted money for a barbecue. He rounded up three teenage friends, each with a long criminal record, and, according to prosecutors, they donned masks, carried guns, and robbed four people, tossing two to the ground. They went searching for more victims in a stolen Kia; shortly after 1:30 a.m. they crossed paths with Aréanah Preston.

Preston, a police officer, had finished her shift and, still in uniform, parked across the street from her family home on the South Side. The 24-year-old was to receive a master’s degree in law the following week. The police department viewed her as a future leader; the FBI had talked with her about a job. The young men in the Kia saw her as a target. They ran at her; a grainy security video shows muzzle flashes. Police and prosecutors say that at least two of the teenagers shot at Preston, who returned fire but was struck in the face and neck. One of the young men grabbed her firearm, and they fled.

Preston’s mother, Dionne Mhoon, had been out with friends in the suburbs and arrived home to patrol cars and swirling red lights. An officer drove her, praying, to the University of Chicago hospital. In a private waiting room, a door opened, and the mayor and a trauma surgeon walked in. We’re so sorry. We did all that we could. She was so brave, your daughter. Mhoon felt ruin. “I had poured so much love into her,” she told me in late September, as we sat in her office on Chicago’s South Side, where she runs a day care. She grew up and raised her daughters there. “It was unreal. I never expected this outcome, never. I don’t know what to make of this city.”

The story of this accomplished young Black woman slain in front of her family’s home gripped me when I first read of it. Preston died in May 2023, but her killing remains a powerful symbol of Chicago’s inability to solve its decades-long violent-crime problem. Mhoon and her daughter tried to ward off the violence around them but still couldn’t avoid it. And Preston’s own department failed her: The ShotSpotter sensor technology the city used marked the sound of eight shots and relayed the address to police dispatchers. Preston’s smartwatch alerted dispatchers to what it detected as a “car crash” and also conveyed the address. Yet, on a busy night for the police, 31 minutes passed before an officer arrived and found Preston lying on the sidewalk. (The police department launched an investigation into the response time. I asked a spokesperson about the status but didn’t get an answer by publication time.)

Preston’s killing was particularly high-profile, but among America’s cities with populations of more than 1 million, Chicago has, for decades, had among the highest rates of homicide. President Donald Trump has seized crudely upon this misfortune and recently described the city as a “killing field.” He has mocked the mayor, Brandon Johnson, and Illinois Governor J. B. Pritzker, and earlier this month he sent 500 National Guard troops to the Chicago area declaring that Johnson and Pritzker “should be in jail.” (Courts have temporarily blocked troops from deploying in the city.)

Democratic politicians have taken the president’s bait. Chicago, they argue, is not as violent as it once was. Crime in some cities in Republican-run states is worse, and red-state gun stores sell many of the weapons that Chicago men slip into their belts and hoodies. Pritzker, who has said that Trump’s threats against the city suggest that he has dementia, took a walk last month along the Chicago lakefront with an NBC reporter. The reporter recited a litany of recent shootings, and asked whether the governor would advise friends to ride the city’s public transit at night. Pritzker waved that off. Trump “has no idea that crime has gone way down in the city of Chicago,” he said. (He added, “Every crime, of course, is a tragedy.”) Johnson recently angered many in Chicago, not least the state’s attorney and police officers, when he insisted that “jails and incarceration and law enforcement is a sickness that has not led to safe communities.”

What these politicians refuse to acknowledge is that violent crime in Chicago remains a serious problem, as I heard from residents there on a visit last month. The number of homicides has indeed dropped from a recent peak of 805 in 2021, and stands at 347 so far this year. But New York City, with a population more than three times that of Chicago’s, has recorded 255 homicides in 2025. The most recent homicide tally for Los Angeles, which has about a million more residents than Chicago, stood at 217. Chicago, in the same year that officials celebrated its “safest summer” in six decades, could end up roughly four times deadlier than New York and twice as deadly as Los Angeles. Chicago is deeply segregated, and homicides remain a plague for Black and Latino young men, who make up the great majority of the killed and the killers. A study of homicides in Chicago in 2020 and 2021, when the murder rate was even higher, found that young adult males who lived in the city’s most violent zip codes faced a greater risk of gun death than U.S. soldiers deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq. The homicide rates in the deadliest neighborhoods remain dozens of times higher than those of Chicago’s safest, mostly upper-middle-class and white neighborhoods.

In total, Chicago registered more than 8,000 homicides from 2010 to 2024, and more than 41,000 Chicagoans were wounded by gunfire in that time. A modern gun is a potent instrument; bullets can hit thighs and arms, or tear holes in intestines and lungs, paralyzing victims from the waist down or leaving them with a colostomy bag permanently affixed to their side. Selwyn Rogers, a top-ranked trauma surgeon at the University of Chicago, wrote a 2023 article in The New England Journal of Medicine about what it was like to treat the terribly wounded: “I fantasize about other possible lives for these patients. What if they had never been shot? What if they had grown up in a safe neighborhood? What if they had a fair chance to live up to their potential?”

I reported on New York’s crack and crime epidemic in the early 1990s, and on the wave of homicides in Washington, D.C., later in the decade. As violent crime fell dramatically in those cities and elsewhere, I wondered why Chicago remained so bloody by comparison. Disinvestment and industrial decline are part of the answer; these forces led about 1 million people to move out of the city over decades, and left many Black and Latino neighborhoods blighted and dangerous. Another is the ineffectiveness of the Chicago Police Department, which has moved far too slowly into the 21st century and has never managed to bring the city’s gangs to heel. Perhaps most troubling of all, the city’s political leadership—which Democrats have dominated for nearly a century—has tolerated disorder for far too long. Some politicians talk of killings as they might of the weather, an implacable force.

Few residents I spoke with said that they want to see the National Guard manning corners on the West and South Sides, although several parents of children who navigate risk-filled blocks to school told me that they did not object to that possibility as strenuously as politicians might imagine. There are far worse traumas. Mhoon recalled laying down rules for her daughters: home before dark, homework done, care for your neighbors and each other. Aréanah followed these rules and prospered. “She’s been fearless since she was a little girl, and I loved that in her,” Mhoon said. “But all I did was worry.”

Walking the streets of the South and West Sides of Chicago, I passed several commercial stretches multiple blocks long where every storefront—what used to be butchers, hardware stores, dress shops—was boarded up and abandoned. Some residential blocks had handsome, well-tended homes. Others were so deserted that they had an almost rural character, with knee-high grasses and alders, red hickories, and oaks.

The commercial buildings of Chicago’s Magnificent Mile feature an exhilarating blend of Art Deco and modern architecture. There are the beaches and marinas along the waters of Lake Michigan, the Art Institute, and the gentrified neighborhoods that run north through Wrigleyville to Evanston. But beyond those parts of the city, Chicago too often feels hollowed out. Its once-formidable manufacturing economy has fallen away, and although finance, insurance, and health care are strong industries, the population has decreased by nearly 900,000 since 1950. Black residents led the exodus. From 1980 to 2017, 391,000 Black Chicagoans left, greater than the population of Cleveland.

I walked two miles west from the 51st Street Green Line L stop to the Back of the Yards neighborhood, where the Union Stock Yards once stood, offering jobs to tens of thousands of immigrants and inspiring Carl Sandburg to write of the “stormy, husky, brawling, City of the Big Shoulders.” A map of the area produced by DePaul University researchers confirms what the eyes reveal: Today, Back of the Yards, across its roughly five square miles, has 478 city-owned vacant lots and another 2,000 or so privately owned vacant lots. Chicago as a whole has more than 40,000 vacant lots, about 9,000 of which are held by the city. Most of these lots are in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods, where years of disinvestment resulted in many thousands of foreclosed and abandoned homes. City officials, fearing that these homes posed a crime threat, were assiduous about tearing them down.

That decision, however, has contributed to physical disorder in these neighborhoods that, in turn, has led to a pervasive sense of menace and fear on many blocks. Chicago officials have talked of plans and more plans but have handed over relatively few vacant lots to local groups and developers, community leaders told me. “We have been cannibalizing our city for decades,” Richard Townsell, the longtime executive director of the nonprofit Lawndale Christian Development Corporation, told me. “It has been planned shrinkage, and it’s asinine.”

Jens Ludwig, the director of the University of Chicago Crime Lab, told me that efforts to rebuild the city’s troubled neighborhoods might be the only social programs that truly matter in attacking violent crime. He pointed to a study in which an organization picked vacant lots at random in Philadelphia and cleaned and beautified them, putting up fences around many; crime fell around those same lots. “Changes to the built environment make a remarkable difference,” Ludwig said.

Townsell’s organization is part of United Power for Action and Justice, a 38-member consortium of religious groups and neighborhood nonprofits that wants to build 2,000 new homes on the West and South Sides. For several years, organizers told me, members have pressured city officials to turn over some 600 lots for a dollar a piece. The group has raised more than $50 million and built and sold 57 affordable homes; another 150 are under construction. (An affiliated organization in New York, East Brooklyn Congregations, has built 5,000 affordable homes, opened public schools, and renovated parks. New homeowners applied pressure to police precincts to crack down on drug corners.)

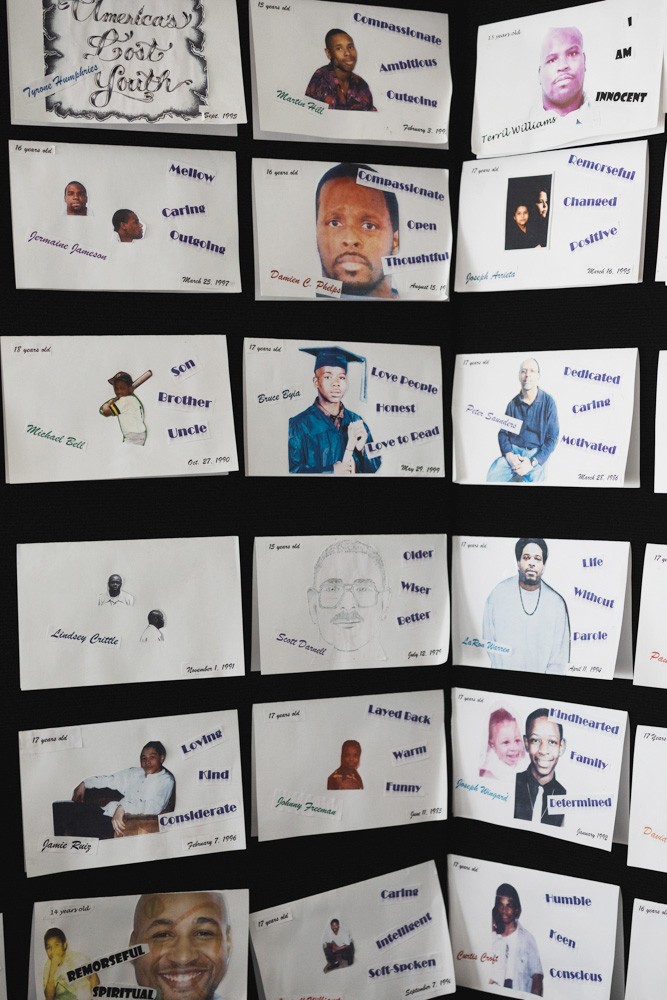

In a former school building that now houses the Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation, a Catholic group that is a member of United Power and focuses on building relationships with families and youth scarred by violence, I met the director, David Kelly. A lean man with a baritone voice, Kelly, a priest, told me that he holds a monthly meeting with mothers and grandmothers. “We have over 100 mothers who have lost children to homicide,” he said. He explained how a desolate landscape amplifies the neighborhood’s threats. “You have such open lands. There’s no grocery store here, no Target, none of that stuff,” Kelly said. “And the kids know it’s dangerous to walk anywhere. Why wouldn’t they carry guns?”

Kelly introduced me to a young man named Joe Montgomery. He was polite and spoke softly. At 19, he had been sentenced to four years in prison for armed robbery. Now 28, he works as a lead mentor at Precious Blood, counseling younger boys. I asked him what it was like to grow up in Back of the Yards. “My friends, we all grew up around each other. We felt okay, right?” He paused. “Then, as time went on, you know, a lot of us died, right? And a lot of us went to jail.” The empty lots, the trees and tall grasses, do not register to him as bucolic. He still does not take casual walks or ride alone on the elevated trains (which were near empty when I got on at mid-evening). When he sees a car pull a U-turn or slow as it approaches, his nerves jump. “I had a childhood friend,” he told me. “She was standing on the sidewalk, and some people killed her. They weren’t aiming at her, but, y’know, it’s not like a bullet has anyone’s name on it.”

He used to shrug this off as just a part of life. “Now I look back at it, like, and think, Goddamn, that’s a traumatizing way to grow up.”

Chicago’s recent drop in homicides has stirred much hope, and it feels unkind to sound a skeptical note. But the city has seen seemingly promising drops in homicides since the 1990s, only to watch violence flare up again.

Part of the problem is that the Chicago police have been slow to modernize. New York City and Los Angeles, thanks in part to leaders such as Bill Bratton and, early on, Raymond Kelly, diversified their forces, offered better training and accountability, and infused data analysis into crime fighting. Chicago is still “a long way behind” New York and L.A., Ludwig said. “Those cities show us that even in an ocean of gun availability, you can reduce gun violence dramatically.” Politics plays a role as well. In Chicago, which last elected a Republican mayor in 1927, police departments were often creatures of the Democratic political machine, not to mention a political force in their own right; the lack of political competition perhaps has given them less incentive to change.

The Chicago police, Ludwig added, have begun to use data in a sophisticated manner, and some police-district captains are learning to work better with local organizing groups. In August, the mayor’s office said that the city’s homicide clearance rate had leapt to an astonishing 77.4 percent. Still, earlier this year, the Chicago Sun-Times reported that Chicago police claimed a high number of “exceptional clearances” for homicides; these were cases in which no arrest was made owing to the death of a suspect or because prosecutors declined to bring charges. Only about 25 percent of Chicago murders led to an arrest, the newspaper noted.

There is also the question of discipline. From 2019 to 2024, according to an analysis by the local PBS station, WTTW, the city spent $491.7 million to resolve lawsuits concerning 1,643 Chicago police officers who allegedly committed a wide range of misconduct, including false arrests and use of excessive force. A ProPublica report earlier this year found that the department frequently failed to investigate officers accused of sexual misconduct. A police department with a reputation for brutality alienates precisely the communities from which it needs support.

The city cannot rely on policing alone, a point often made by the mayor, who lives with his family in the Austin neighborhood, where gun violence runs high. Many neighborhoods on the South and West Sides of Chicago have long been dominated by gangs: the Vice Lords and Latin Kings, the Black Disciples and the Gangster Disciples. Federal investigations have brought down leaders, but gangs in turn have fragmented into loose affiliations of young men laying claim to desolate turf. What sparks them to violence can be hard to pinpoint, former members told me. Some beefs are so old that younger gunmen lose track of the origin story. Social media plays a pernicious role. One group mocks another—a guy kisses another guy’s girl on TikTok, say—and young men with guns start saying they want to “light up someone’s ass,” as Montgomery put it.

In the past few years, city officials, philanthropists, businesses, and community-organizing groups have worked to short-circuit the impulse to pull out a gun and shoot a rival or just someone who annoys you. The notion is that violence interrupted is violence delayed, which opens an opportunity for an intervention. Arne Duncan played basketball as a teenager in gyms across the South Side and lost mentors to gun violence. He later served as Chicago’s school chancellor and President Barack Obama’s secretary of education. Of late, he runs Chicago CRED, which, along with many other community organizations, fields an army of more than 1,200 peacekeepers and violence interrupters. (Duncan is also a managing partner at Emerson Collective, the majority owner of The Atlantic.) CRED’s work is challenging and can leave him sounding haunted. “In my seven years heading the schools, we lost a child every two weeks. Today I saw the mom of a child who had been killed on the bus going home,” he told me one evening. “Now I find myself trying to negotiate a gang peace with a 17-year-old.”

To work with these boys and men requires diplomatic skills and an appreciation for the blustering insecurities of young people. Cedric Hawkins is a CRED violence interrupter in the Roseland and West Pullman neighborhoods of the South Side. He has an easy swagger that speaks to his own decades on the street; he served a 10-year sentence in federal prison for dealing heroin and cocaine. He took me for a drive around the neighborhoods where he grew up and now works. Hawkins pointed to a corner where three teenagers had died, a bungalow once used as a drug traphouse, an avenue where seven young men died in a single shootout in 2020. He slowed his car as he eased it through the gully that was the site of his first gun bust, at age 12. Hawkins told me that he has lost eight cousins and an uncle to gun violence. He’s the rare one who made it into his 40s.

When he got out of prison, he cast about for work. Some friends suggested peacekeeping. “They say, ‘You didn’t tell on nobody. You took your sentence like a man. People respect you,’” he told me. “But to be honest, I was reluctant. I didn’t want anything to mess up my negative credibility.” Once he tried mediating, his view of himself changed. He saw the work as compensation for all the pain he had brought to the world.

He explained his diplomatic arts. If groups are beefing, he tries to negotiate a nonaggression pact. “We’re not saying you all got to love each other. Just agree to stay off each other’s turf and play defense, cool?” This means that gang members agree not to cross a truce line. “You saw Trump trying to tell Ukraine what to do?” Hawkins said, wagging his head. He explained that the president was trying to dictate terms to warring parties. “That’s not the way to do it. You let one side say what they can do, and you let the other side give their line.” When a nonaggression pact turns into a peace agreement between two gangs, Hawkins and CRED try to cement it with the promise of education, jobs, and therapy. The offer of therapy piqued my interest. Hawkins was surprised at my surprise. “Around here, we got trauma coming out of the womb,” he said.

I asked Duncan whether all of this could really work. Can former gangbangers—and the assumption that all are former gangbangers requires a leap of faith—actually help police tamp down homicides? He said he is aware that some peacekeepers might be a “foot and a half” away from their old lives. But he pointed to the city’s recent decline in homicides as a promising sign. His hope is that peace begets peace, even as he harbors no illusion of a miracle. He mentioned New York’s much lower violent-crime rate and said, “My goal is just to be normal for a big city.”

Nine days after Aréanah Preston’s death, Johnson delivered his inaugural address as the new mayor. A candidate of the left, he had once described incarceration as a “racist system,” and promised during his campaign to end the ShotSpotter technology, which he argued is susceptible to human error and can encourage cops to act too quickly. (Johnson discontinued the city’s use of the technology in 2024. A majority of alderpersons representing Black and Latino districts have voted to keep ShotSpotter, and some claim that the mayor is putting Black and Latino lives at risk. Surveys suggest that most Black and Latino residents also favored the technology.) In his speech, Johnson invoked Preston by first talking of Adam Toledo, an armed teenager who two years earlier had fled in the dark from a cop and was shot dead after dropping his gun. “The tears of Adam Toledo’s parents are made of the same sorrow as the parents of Officer Preston’s parents and relatives,” Johnson told a cheering crowd. (Johnson’s office didn’t respond to interview requests for this story.)

Johnson was correct when he said recently that National Guardsmen “occupying our city” would solve more or less nothing. Pritzker, too, was correct when he told the NBC reporter that big-city crime is inevitable, although that sidesteps the particular tragedy of Chicago’s high homicide rate. The National Guard deployments, although significant for the country and our sense of our democracy, are in most respects a sideshow in Chicago. At the same time, Trump doesn’t entirely miss the mark when he lambastes generations of political indifference to so much suffering. When he deployed the National Guard in Washington, D.C., crime fell.

What is striking, infuriating even, is that Dionne Mhoon speaks with more honesty and compassion than any one of these leaders about ending the city’s violence epidemic. She is herself dubious that the National Guard can accomplish much. They are not, she told me, intimately familiar with Chicago’s troubled communities. But she sees a deeper pain and deterioration that often goes unaddressed by politicians. When she went to watch the bond hearing for the young men charged with her daughter’s murder, she told the press that she was praying for the accused even as she wanted them imprisoned. (All have pleaded not guilty, and their cases have yet to go to trial.) Afterward, she told me, family members and friends of those young men crowded around her, as if trying to draw her into a fight. (Two law-enforcement sources confirmed Mhoon’s account to me.) She told me that she has received “dozens” of anonymous threatening phone calls and letters. At one point, the police department posted a patrol car outside her house for a month. “There has to be some accountability in the households. Like, we can’t blame the mayor or the superintendent if your child is on the street at 11 p.m.,” she said. “Too many in our communities are detached from values and morals.”

Mhoon has started a foundation in honor of her daughter, with an emphasis, she told me, on reaching precisely the at-risk children who too often grow up to become victims and victimizers. She volunteers weekly at public schools on the South Side. She talks with young girls, telling them that they matter. She speaks with boys too, hoping to break the cycles of violence that claimed her daughter’s life. “I talk about thinking about their choices, and their long-term effects, however hard that may seem,” she said. “Too many are clueless about love. They don’t have it, and they don’t know it.”

I asked whether her work offered any salve for her loss. She took off her glasses, rubbed her eyes, and shook her head. There’s no healing, she said. “Even when I’m pumping gas, I look around and think, Do you know what I lost? You don’t have a clue,” she said. “Then I hear every other day of another kid getting shot, and I wonder: How do we make it end?”

The post The Problem With Minimizing Chicago Crime appeared first on The Atlantic.