Photographs by Jedrzej Nowicki

Two Russian soldiers emerged from the woods and walked slowly down a dirt road, seemingly unaware that they were being monitored from the sky. By the time they raised their rifles to fire at a buzzing Ukrainian drone, it was too late: The drone had dropped a bomb that exploded with a bright-orange flash on the ground between them. But as the smoke drifted clear, the soldiers got up and staggered into the trees. The first strike had failed.

I watched all of this on a screen from a Ukrainian command post about 10 miles back from the front line.

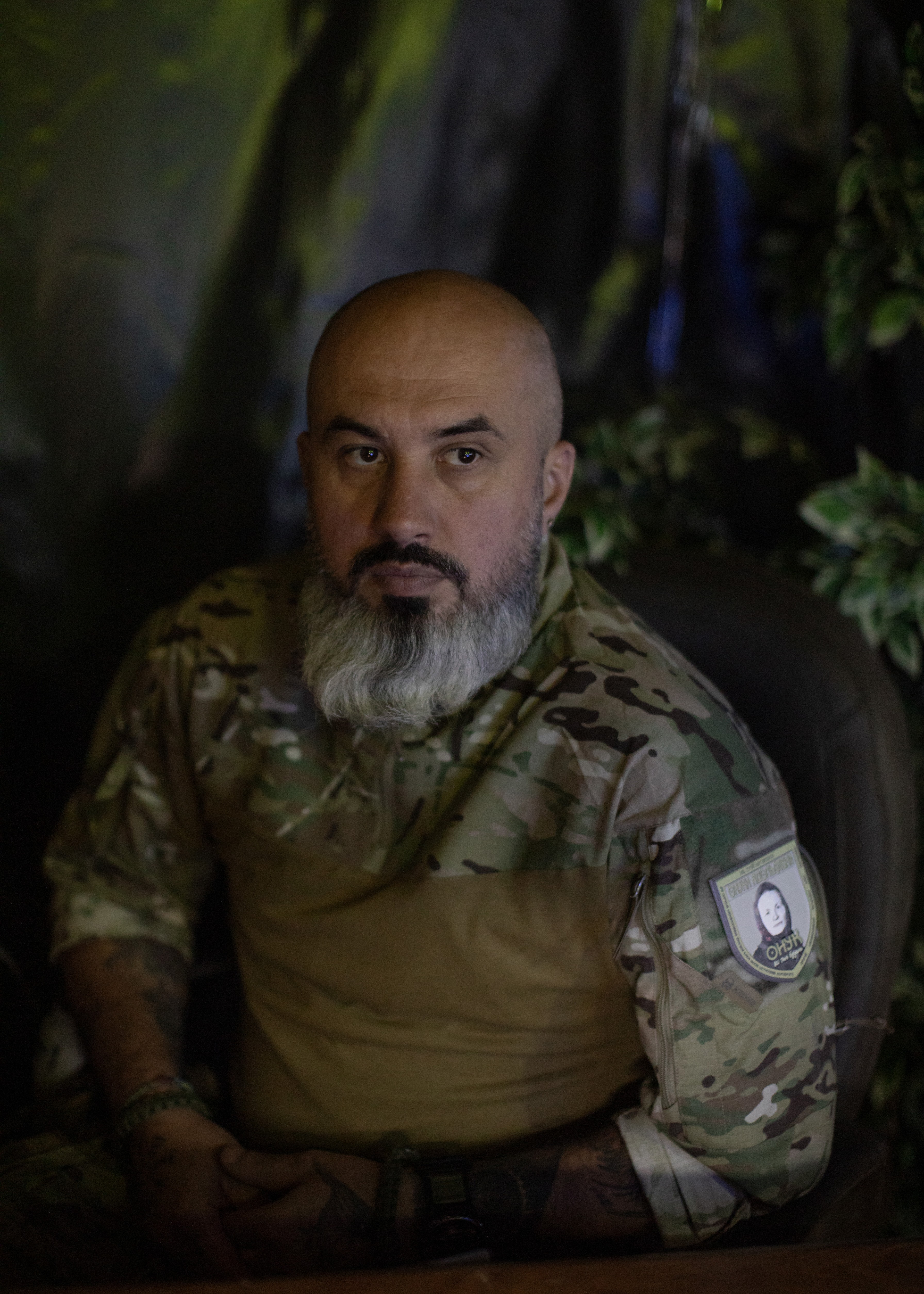

“We know the two wounded Russians are in those trees,” said the Ukrainian commander alongside me, a powerfully built man of 39 who goes by the call sign YG. He didn’t look happy. The Russians probe the front line every day in small groups, and his job is to stop them while doing all he can to protect his own, far more limited supply of soldiers. But drones were not his only weapons against these two.

Ukraine is fighting a war of attrition. Any hopes that might have been raised by President Trump’s red-carpet diplomacy with Vladimir Putin have expired, and it is impossible to spend more than a few minutes near the front line without being confronted by Ukraine’s greatest vulnerability: lack of soldiers. Yet I came away from a recent trip to Ukraine believing that the country may actually be able to achieve its military goals.

Despite Russia’s demographic advantage, its efforts to envelop Ukraine’s formidable fortress belt—a string of strategic cities and logistics hubs in the country’s northeast—have had little success. Capturing the belt would take several years of hard fighting, given Ukraine’s recent success in damaging Russia’s oil pipelines and rear bases. Putin tacitly acknowledged Russia’s failure by demanding that Ukraine voluntarily cede the entire region in August, an idea that no one took seriously.

All of the officers I met with, during a week in northeastern Ukraine, told me that the key to keeping the Russians at bay lies in finding better ways to compensate for Ukraine’s desperate shortage of manpower. Part of the answer is drone technology, which has done a great deal to help Ukraine protect itself in an uneven fight. But commanders are now taking a range of other measures to minimize casualties, including more careful use of artillery, more precise troop movements, and better rotation plans. “Our main purpose is to not let direct contact happen, so Ukrainian troops don’t have to engage,” one local commander told me.

When I was last in the country, nine months ago, Ukraine appeared to be in real trouble: Its weapons pipeline was lagging and Russia was grinding forward on the front lines with what Ukrainian infantrymen called “meat waves” of seemingly expendable soldiers and mercenaries. Now there appears to be a new confidence that Ukraine is reorienting its institutions for a long war, learning quickly from the battlefield and continuing not just to inflict steady losses on the enemy but also to limit its own. “Russia cannot win unless we in the West totally quit,” Ben Hodges, a retired general who commanded U.S. Army forces in Europe, told me. Time, which has until now favored the Russians, may be shifting to the Ukrainian side.

When I visited YG’s command post, a branch of Ukraine’s 66th Mechanized Brigade, he told me he had been forced to delay an evacuation of three wounded soldiers from the front because he didn’t have enough men (one of the soldiers had to have an arm amputated as a consequence). He didn’t want to risk any more lives. After we saw the two Russian soldiers survive the Ukrainian drone strike and then hide in the woods, I noticed the frustration on YG’s face. He suspected that the soldiers were concealed in a dugout in the trees, a possible base for deeper incursions into Ukrainian territory. He asked one of his subordinates—they were seated at desks beneath a wall of screens showing parts of the front line—to contact the drone pilot in question and chastise him for not aiming more carefully.

YG then called in artillery strikes. We watched as the first one struck about 20 yards from the trees where the Russians were hiding. The second landed on the opposite side but almost as far away, leaving a visible crater in the earth. It was time to send in an assault team.

The closest Ukrainian soldiers were several kilometers from the site, and the Ukrainians did a careful reconnaissance before sending four men on foot. An elite Russian drone unit was hunting for targets.

Eventually, the Ukrainian infantry team emerged on our screen. The soldiers were making quick, cautious dashes from one patch of tree cover to the next, staying out of sight as much as possible. Their route had been laid out in advance and divided into sections, YG told me; they had a designated time to reach each landmark programmed into their phones, and reconnaissance drones monitored their progress.

All of this caution formed a stark contrast with the obvious recklessness of the two Russians I had seen earlier. “They send guys knowing they will be targeted, as decoys,” YG said. “Some troops they see as disposable. The better-prepared ones attack somewhere else. This caste system of the Russian army also applies to evacuation. If a low-level guy is wounded, 99 percent they will not pick him up.” Not long before, YG said, he had overheard calls from a wounded Russian soldier pleading in vain to be evacuated; in the end, the soldier amputated his own leg.

I had to leave YG’s command post before the assault team reached its target. The following day, I asked a spokesperson for the unit what had become of the two Russian soldiers in the trees. He seemed uncertain which soldiers I was referring to, which isn’t surprising; that part of the front line sees about 43 assault actions by Russian forces every day, and about 100 glide bombs a week, YG had told me. “I’m not sure,” the spokesperson said, “but I think those Russians are not alive anymore.”

YG had pointed out something else to me: Some of the soldiers seated in desk chairs under the screens were set to head out to relieve the drone crews in the field. “Rotation is a way of conserving manpower,” YG said. This is especially important for infantry soldiers, whose job is the most physically demanding and who can be out for 50 days or more. “If they know they are not stuck there, it helps,” YG said.

Some of these measures may sound rudimentary, but they are not taken systematically across the battlefield, partly because Ukraine doesn’t have enough well-trained commanders, Mykhailo Zhyrokhov, a Kyiv-based military analyst, told me. In some cases, he said, soldiers have deserted from one unit to another “because they know the commanding officer there is using manpower in a more responsible way.”

Even the locations of the command posts I visited reflect the imperative to minimize casualties. They were mostly in private homes, where they couldn’t easily be identified from the air, and they were designed so that they could be evacuated almost instantly if their location was discovered—as had happened recently with one of the units I visited. The commanders always have the next location scouted out in advance.

Members of the military drove me to their bases in ordinary civilian cars, not military vehicles, which can be spotted from above and targeted. I saw very few officers or soldiers in uniform in Ukraine, because the Russians will use drones to chase and kill a single person. Even far from the front line, soldiers tend to dress casually—presumably because of the risk of spies or saboteurs.

Ukraine is also becoming dependent on ground drones: remotely driven robots that run on wheels, tracks, or even legs. Used for resupplying and evacuating troops, these drones often travel more than 10 miles without stopping but are vulnerable to changes in terrain; each trip involves dozens of people behind the scenes. A drone-unit commander at another outpost, who uses the call sign Staryi, told me that soldiers being evacuated by drone also need to be familiar with the machines. Recently, he told me, a soldier with injuries to his arm and his head was being evacuated by a ground drone when the machine unexpectedly stopped. The soldiers monitoring him from the air weren’t sure if he was still conscious (he had suffered a blast injury). But to their surprise, the wounded man got off the drone, pushed it until it started again, and hopped back on.

Staryi’s command post outside Kharkiv looked less like a base than like a tech-industry office, with long-haired young men in T-shirts hunched over screens and sipping espresso drinks. A day earlier, I had met a first-person-view-drone pilot who looked like an adolescent gamer, with a near-skeletal physique and a nerdy grin. He did a demonstration for me in an open area that his brigade uses for target practice, making the drone flip and spin with a skill that was beautiful to see. He had killed about 200 Russians in the preceding year, one of his fellow pilots told me. That is the kind of rate Ukraine will have to maintain in order to survive as a nation.

The drone war’s weird intimacy is startling to witness up close. When a drone operator zooms his camera in on trees by the front line, the magnification is so powerful that you can see a single leaf trembling in the breeze. It is hard to fully take on board the reality that what you are seeing is happening in real time and that a few keystrokes can lead to the death of whoever is hiding among those trees.

One afternoon, I sat on a couch with Lieutenant Leonid Maslov, a former lawyer who leads a drone-reconnaissance unit, as he scanned for potential targets with a MacBook on his lap. It was raining, and his deputies kept glancing around, unsure whether what they were hearing was thunder or an air strike.

“They’re trying to spot infantry,” Maslov said, as the camera zoomed in on a gap in the trees. “Maybe somebody will die now.” He let out a big, hearty laugh.

Maslov’s screen showed 30 little boxes, each of them a camera feed or a live map. One revealed a dozen little yellow dots hovering near the front line: enemy reconnaissance drones. A year ago, Maslov said, there would have been about 50 of them, including several right over our heads. That changed when Ukraine gained the ability to take them out with cheap attack drones.

After 15 minutes of scanning, we hadn’t located any new Russian soldiers, so Maslov showed me footage of some of his unit’s recent exploits. In one, a Russian tank charges along a dirt track, sending up clouds of yellow dust. A Ukrainian drone sails down from the sky and strikes it, sending up a plume of fire and smoke.

“You see that?” Maslov said. “The tank’s hatch is closed. Three Russians are getting slow-cooked.”

I flinched a little at the callousness, which I heard a lot of in eastern Ukraine. The reasons for it aren’t hard to find: This is a place where Russia routinely bombards civilian homes. Anyone in Ukraine can hear (or read) the Russian state media that portray Ukrainians as rats, hyenas, and filth, and that has had an effect. Once, at a café in Izium, I saw a young woman in a T-shirt that had an image on the back of a masked man holding up a severed head in one hand and a knife in the other. Below were the words Kill the Russian. No one is the least bit surprised by this kind of thing.

“We hate them for the fact that we have lost our compassion,” Andrii Bazarnyi, the presiding doctor at a field hospital near Kharkiv, told me.

The hatred is a reminder that, for Ukrainians, this war is elemental. Scarcely anyone I met seemed to have any doubt that their way of life would be destroyed by a Russian victory, which would in all likelihood result in their killing or imprisonment.

How much longer can Ukraine maintain the fight? No one has a clear answer. In Kyiv, I asked a recruitment officer, and he seemed to wince a little. “We just mobilized a group of 30 men,” he said. “A few of them fled the country, some others said they were sick, others claimed injuries. In the end, only eight made it to the training center.” But, he said, the people who enlist before turning 25—the age when Ukrainians can be drafted—make very dedicated soldiers.

I put the same question to YG.

“We’ve been at war with the Russians for 300 years,” he said. “We can hold on for a while longer.”

The post Ukraine Might Be Winning Its War of Attrition appeared first on The Atlantic.