Getty Images; Tyler Le/BI

A favorite adage of economists, market watchers, and financial journalists alike is that the American consumer is the engine of the US economy. If spending is not slowing, the thinking goes, the economy and labor market will be fine. It’s true that consumer spending represents a significant share of the economy, accounting for roughly two-thirds of the country’s GDP.

The truism is inspiring optimism about the economy’s current trajectory, given the recent strength of retail sales and other data on how people are spending their money. I think the causality here is backward. A consumer slowdown is never the precipitating cause of an economic slump. Usually, consumption falls after employment materially cracks. When Americans stop spending, by that time, it’s already too late.

While Americans continue to spend their way through their troubles, it may not prevent an economic slump from taking hold.

The notion that consumer spending can save the country from a recession contradicts several historical trends. For starters, consumption has managed to grow modestly in previous economic slumps. In several of the post-World War II recessions — 1948, 1970, 1982, and 2001 — real consumption expanded during the downturn. In other words, during those recessions, the best that spending could do was to help economic conditions from deteriorating further, cushioning the blow rather than preventing it altogether. In other periods of negative growth, consumption declined substantially, so that on average, its contribution to GDP during recessions is close to zero.

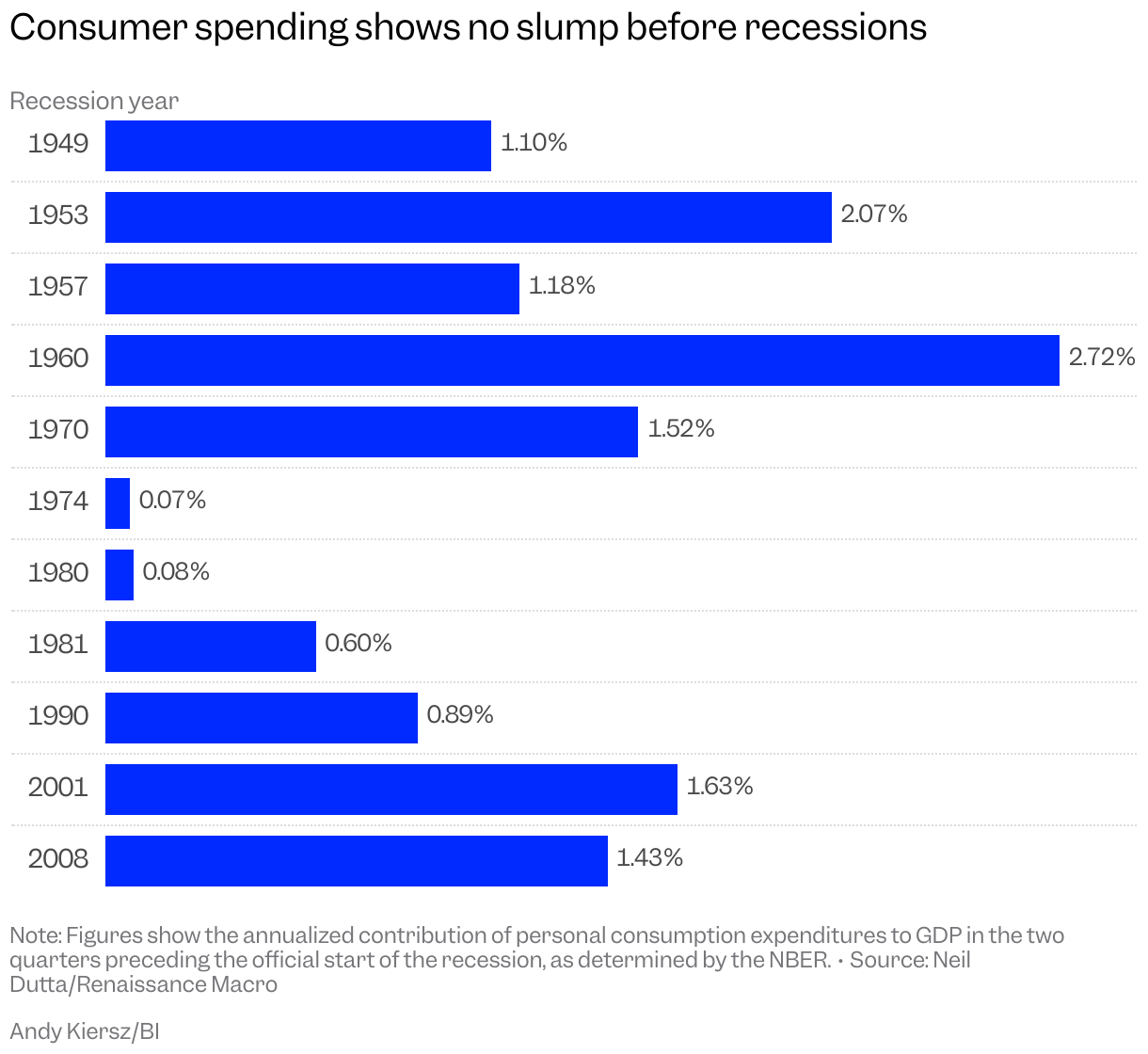

Next, consumption has never declined before an economic slump; it’s always happened after the economy began to go into the tank. Therefore, the growth in recent quarters does not look especially unusual. Assuming tracking estimates for the current quarter end up in the ballpark, average annualized growth in real consumer spending is expected to run at about 2.2% in the first two quarters of 2025. This is slightly slower than consumption growth in the two-quarter period preceding each of the last three recessions, but it’s hardly out of the ordinary.

Let’s deepen this analysis by breaking out the various types of major spending: durable goods, such as washing machines and TVs; nondurable goods like T-shirts and groceries; and services, encompassing everything from restaurants to movie tickets. Prior to previous recessions, the most common signal from these categories was Americans cutting back on big-ticket durables rather than cutting spending in service industries. As our figure shows, going back over the past 11 cycles, people decreased their expenditures on durable goods in the two quarters preceding the recession just over half the time. And during recessions, durable goods spending tends to fall while spending on services holds up. So far this year, spending on durables has been about flat. At the very least, this suggests a degree of caution among Americans when it comes to making big-ticket spending decisions that could portend more trouble coming down the line.

One confounding variable, of course, is the degree to which President Donald Trump’s herky-jerky tariff announcements are influencing the data, creating a push and pull in consumer behavior regarding durables. The threat of tariffs may have prompted people to pull forward activity, making big purchases before anticipated price hikes, while the hope for tariff removals might cause consumers to wait it out. On the other hand, the big story in the first half of this year has been the slowing of services spending, which is likely less sensitive to tariff news. This suggests that if you’re waiting for the consumer to make a call about a turn in the business cycle, you’re likely waiting too long. The recession red light is already lit by the time consumption contracts, and sometimes it does not fall at all.

America’s job market is looking weak

The better indicator to watch, if you were trying to anticipate a recession, is the labor market. While consumer spending has been doing quite well in recent years, the job market has been cooling. In 2023 and 2024, real personal consumption expenditures expanded 3.0% and 3.1%, respectively. Despite this, the unemployment rate rose by 0.3 percentage points in each of those two years. So far this year, the unemployment rate is on track to increase by another 0.3 percentage points.

Key areas of the jobs market appear to be slowing. First, the bulk of recent job growth has been in industries that are not correlated with the economic cycle, such as healthcare. And even in those still-expanding sectors, growth has been slowing lately. If that trend continues, it’s hard to see what other industries will be able to pick up the slack. Second, areas of the job market that follow the ups and downs of the broader economy — specifically, goods-producing jobs — have already been contracting. Third, despite “loose” financial conditions, such as a rising stock market and falling interest rates, which are generally thought to be supportive of hiring, labor markets have now reached a point where the level of unemployment exceeds the number of job vacancies.

If consumption is the end-all and be-all of employment (“sell more stuff, hire more people”), why has the labor market slowed to begin with? There are clearly other areas of the economy that determine the strength in the labor market than just consumption.

The worrying slide of business investment

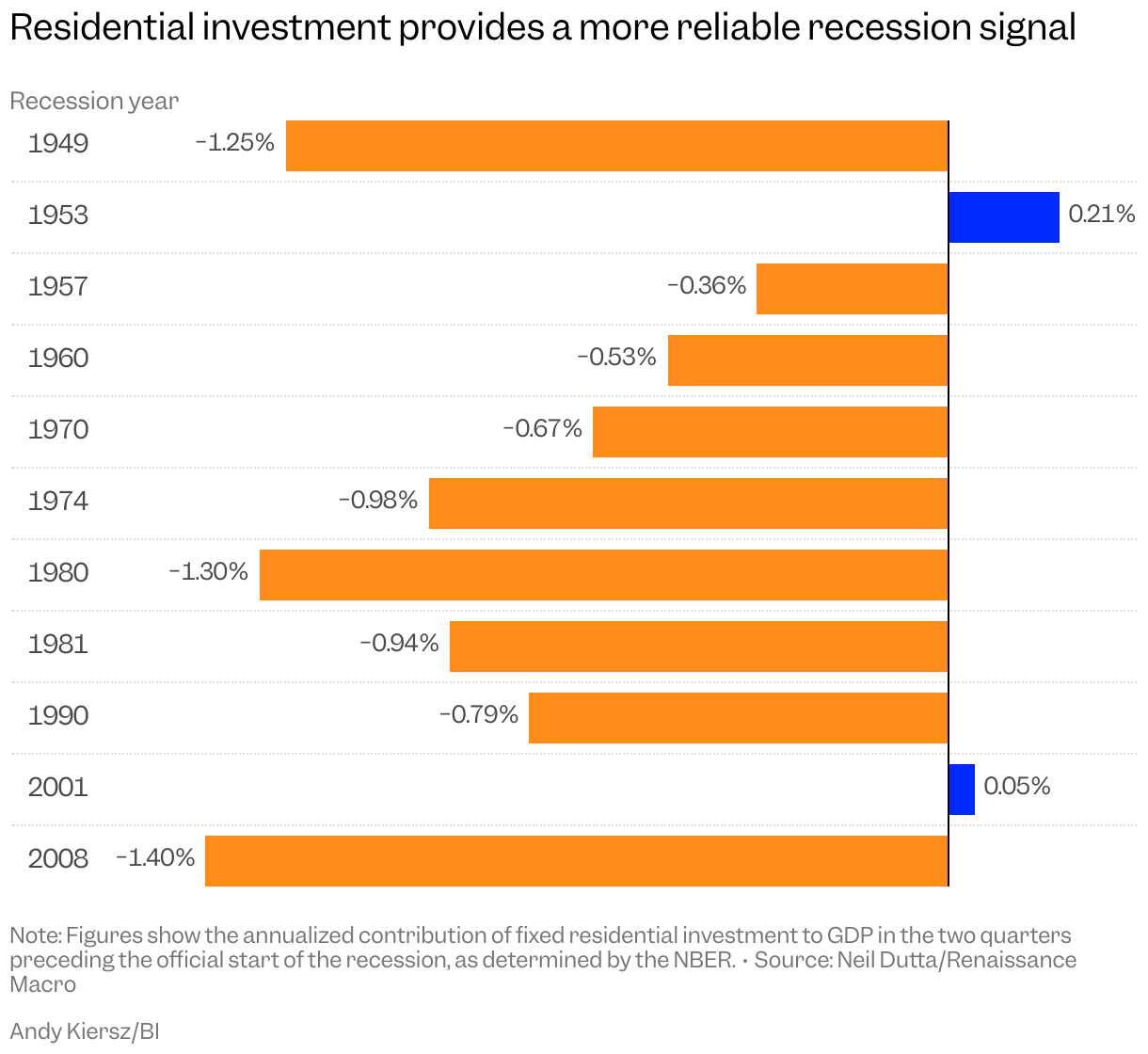

The state of business investment is another reliable indicator of a recession. During a recession, nonresidential business investment — which excludes spending on homebuilding — always contracts, while residential investment almost always declines (2001 was the lone exception). Moreover, in the two quarters before a recession, the contribution of residential investment to GDP growth is negative (again, with the recession that followed the 2001 tech bubble being an exception) while the contribution of nonresidential business investment tends to be positive. To the extent any one sector provides a tell, it’s the homebuilders. And, bad news, residential investment has been contracting for five of the last six quarters.

When it comes to the drop in homebuilding investment, there is some possibility of a false signal. In fact, this is not the first time residential investment has declined in the post-COVID era. In 2022, as an example, there was a notable decline in residential investment. However, there are some important distinctions between then and now that make this current decrease more concerning.

- Government spending and investment were a meaningful tailwind to GDP growth. By the fourth quarter of 2022, government spending and investment were adding about as much to GDP as residential investment was subtracting. By contrast, government spending and investment have recently been slowing, resulting in a modest drag on GDP.

- Through most of 2023, units under construction were elevated. Even as they slowed new construction, homebuilders had a substantial backlog of homes to work through and continued to add construction workers to their ranks. Nowadays, by contrast, no such backlog exists. With housing starts running below completions, units under construction have more room to decline.

- Finally, households were still drawing down pandemic-era excess savings, supporting consumption at a time when housing was slowing. Pandemic-era excess saving was drawn down completely sometime in 2024. That puts the onus on labor incomes as the primary driver of consumption now.

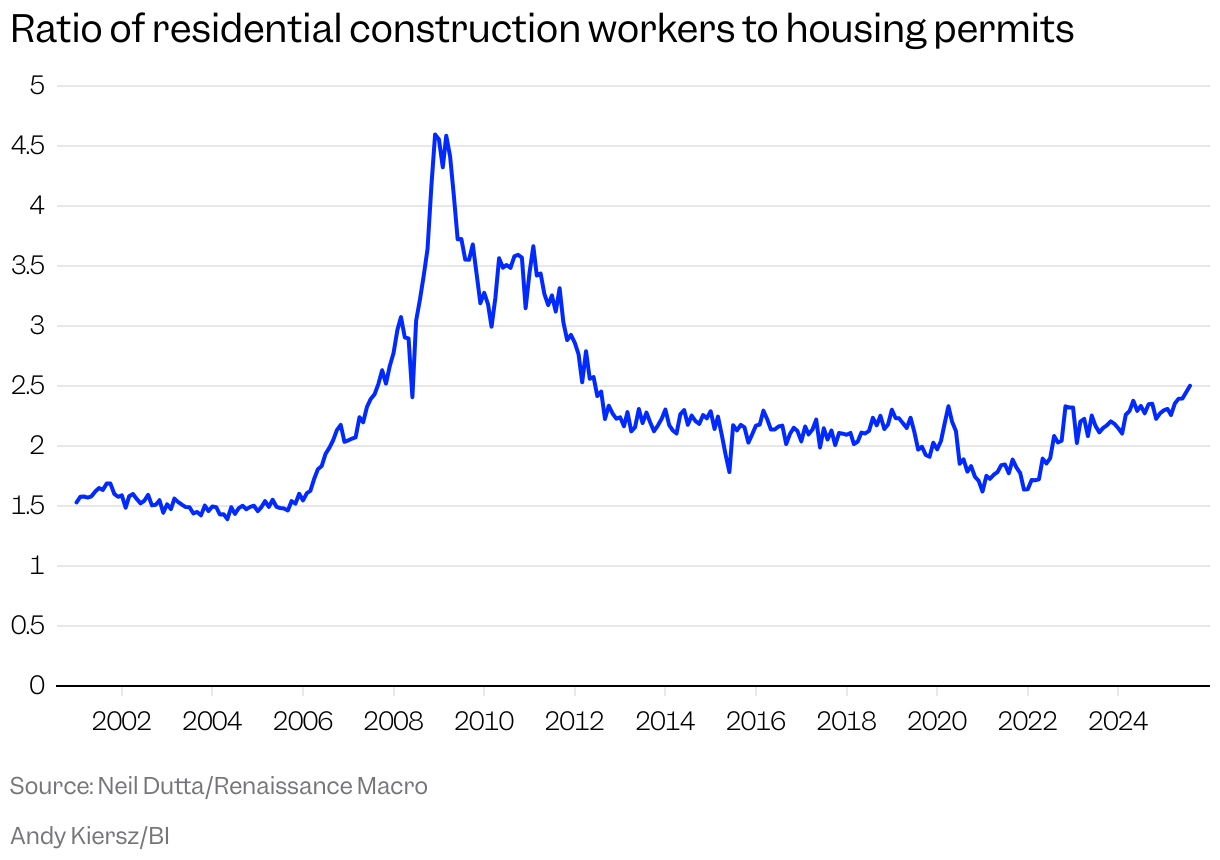

There are reasons to assume that the slowdown in residential construction might matter a little more for the broader outlook than it did before. Indeed, a crude analysis suggests that more layoffs could be on the way for residential construction jobs. As of August 2025, the ratio of people employed in residential construction to housing permits stands at 2.5, the highest level since 2012. This ratio is about 10% higher than its average in 2024, meaning there is likely a large pool of construction workers waiting around to do something. There’s no need to hold onto workers who are not doing anything. To return this ratio to its 2024 average, assuming the number of new monthly permits issued stays steady, implies a decline of 304,000 jobs. Spreading this over the year implies a decline of 25,000 jobs a month. Even if this is even half-right, it’s still a significant headwind, considering private employment is running at just 30,000 a month to begin with.

In my client meetings, the pushback to these concerns typically goes like this: AI is booming, stocks are up, and wealthy consumers are still doing well. I really believe those three bright spots are, at their core, a single story. And even as this asset-driven boom has marched on, that has not kept broader labor market conditions from continuing to worsen. So, if you’re banking on the consumer to simply hold everything up, you might be late to catch a more material slowdown in the economy. It’s better to be prepared than surprised.

Neil Dutta is head of economics at Renaissance Macro Research.

Read the original article on Business Insider

The post Americans are spending like mad. It may not be enough to stop a recession. appeared first on Business Insider.