The city of Southend in Essex—the county that separates London from the shores of the North Sea—is a place with a rich subcultural history. After World War II, successive waves of style tribes would meet up on the beaches of Southend to beat each other senseless. After kicking and punching their way through the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s, the Teddy Boys, punks, mods, rockers, skinheads, suedeheads, and bikers who decorated Southend in each other’s blood probably didn’t expect the place to go quiet. But for a while, it did, as the mainstream and its tracksuited practitioners of less choosy violence had the local freaks and Southend’s subcultural reputation in a chokehold.

Then, at the start of the new century, something started to crystallize. The loving undercurrents of psych rock, post-punk, fruity European synth music, and dub reggae started to find their way out through a new generation of party-loving Essex weirdos who combined esoteric tastes with high-street hedonism, leading to the creation of Junk Club.

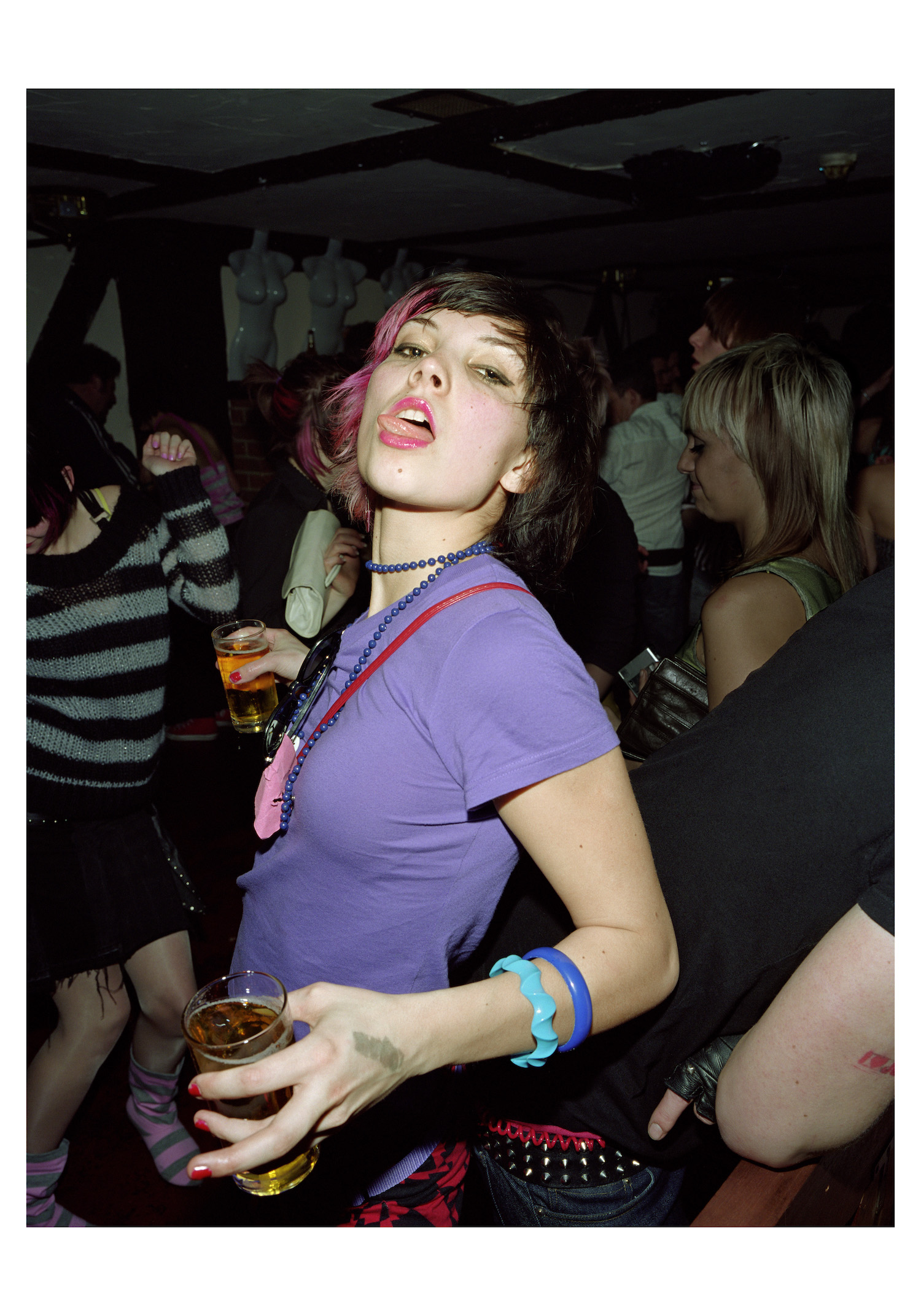

Based at the Royal Hotel on Southend seafront, Junk was founded by Rhys Webb and Oliver Abbott in 2002, and they were soon joined in their efforts by designer Ciaran O’Shea who alongside photographer Dean Chalkley gave the club night and its surrounding social scene an intoxicating, intoxicated face to show to the wider world. Soon, hundreds of teenagers, university dropouts, and actual schoolchildren were dancing, snorting, and shouting their nights away to a soundtrack of no wave, electroclash, and drum and bass.

Bands like The Horrors (co-founded by Webb), These New Puritans, Ipso Facto, Xerox Teens, and The Violets all took their first steps at Junk and a strong turnout of its regulars on a new social media site called MySpace ensured the enraptured attention of style magazines from all over the world. At one point, Hedi Slimane—then head of menswear for Christian Dior—came to Junk, stole fashion ideas from all the best dressed 15-year-olds in the room, then turned a load of them into catwalk models.

It was a wild time, and though its founders would rightly wince at the terms, a lot of what constitutes the “indie sleaze” and “Hedi boy” viral crazes of today can be traced back to that strange basement in Southend.

VICE called up Webb, Abbott, O’Shea, and Chalkley to chat about Junk Club and its legacy, ahead of a special one-off event at the Beecroft Gallery in Southend on Saturday, October 4. Rats: Confessions of a Teenage Junkie is part-celebration and part-seance, with booze, a live Q&A, and a secret special guest musical performance thrown in to boot. Tickets are here.

VICE: What were your memories of England in 2001, before Junk.

Ciaran O’Shea: Being in England is one thing, being in Southend I suppose is another. Pre-Junk, I spent most of my time traveling up to London to places like Bagley’s and Stratford Rex, trying to escape where I was from. Looking back on that time, a lot of it was spent with people pretending they weren’t from Essex, it was almost a dirty word. When people you’d meet on holiday asked, “Where are you from?” you’d just say “near London.” So I spent a lot of that time listening to jungle and early dance music that took you somewhere else.

Rhys Webb: Ollie and I had been immersed since our mid teens in underground 60s music. We had an amazing time listening to records in Essex and Southend. There were mod nights like Almost Grown, which still runs today. There wasn’t any contemporary music that affected or motivated us. Then there was this first wave of music, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ first EP and the Detroit scene, with the White Stripes and the Hentchmen. It was the first world of music that was brand new and felt like it was our time to listen to, which motivated us to start the night.

Oliver Abbott: I liked going to London and being from Southend. There was always a novelty factor of going to mod clubs and it’d be like, ‘Oh, you’re the Southend crew.’ From the 60s to the revival era, Southend was known for mod, so it was a badge of honor you wore up there.

What was your gateway into that world? It’s not the sort of music most teens listen to.

I was 13, and I’d never heard of mod before. I was with a friend, looking for Quadrophenia on video, which his dad was making out to be some really “bad,” Clockwork Orange-style film. It wasn’t but it really resonated. I found out I had a lot of family connections with that scene and suddenly you’re just aware of this whole world.

Dean Chalkley: I’m a bit older—Ollie’s talking about his mod family and I knew them, I was going out with them when he was still a kid—but by 2001 I’d moved up to London and was immersed in house music. It was the golden era for many people but it was starting to plateau and there was this new energy and excitement coming through with guitar bands. I started working for the NME for that reason, and 2002 was when I started to photograph The Strokes and the White Stripes and things like that. It was this crossover period, the end of a time where house music was massively exciting and then this new thing was emerging which had elements that crossed over into the electronic side. When I first went to Junk, it was like, ‘Oh wow, this is amazing. This really feels like some kind of resistance.’

Rhys Webb: We were always going out on the Southend scene, so it wouldn’t be unusual for us to go to house or jungle nights, or to hear drum and bass played in the local bars. Once Junk had started we’d go up to Rough Trade every Monday and dig through the new releases, everything from crazy, angular no wave to the emerging electroclash scene. We were just lapping it all up and that became the ethos of the night, to focus on this brand new moment.

People always talk about that era being very cross genre. Was there anything underlying in the various types of music you were listening to that tied them all together?

We were always into dance music, whether it was 60s R&B, jazz, “Super Sharp Shooter” or Frankie Knuckles. Going out to clubs was our life, from the age of 14 onwards, and the whole thing was just to do a great party where people would dance to the music.

Dean Chalkley: There was an angularity to it. Not necessarily always spiky guitars; it could be dub reggae, but the rhythm would usually still be angular.

Oliver Abbott: If there was like, a tentacle that spread through the town, I think it was just what was going on in Southend and that’s why it was cross genre. It was all good stuff, it wasn’t like one of those other indie clubs that sprung up at the same time. We always had a bit of an edge because we were playing acid house, jungle, and dancehall. I don’t think a lot of the other clubs in our world could do that.

Rhys Webb: We were trying to find the weirdest stuff because we’d always been into digging the obscurities. Certainly there was a real no wave, post-punk kind of theme. We were digging right into the No New York compilation when other people were just playing Maximo Park.

You definitely never heard Kaiser Chiefs at Junk.

We just didn’t ever play any of that. We just went headfirst into somewhere a bit deeper.

Ciaran O’Shea: I met Rhys around his 18th birthday. He called me behind the DJ booth, opened his record box, and he was like “have a look.” It was such an alien thing for me, this love of collecting records, and people who love the depth and breadth of music. With Junk, you’d have a record played and then within a few days you would’ve charted the lineage of it back—that inspired this, which inspired this, which inspired this… it was like an education in sounds. Do you know what I mean? It was a beautiful, beautiful thing.

Dean Chalkley: Honestly, when you think about Southend and the surrounding area, there’s so many people that have got amazing record collections, way disproportionate to everywhere else. There’s a veneer which could be the seafront but then behind that you’ve got a counterculture. People there dive so deep into subculture, and they have done for decades.

I try to remember all the tracks that I heard down Junk, and I can’t, it’s just one gigantic bulge of music but also expression and people and smell and grit and grime and overflowing toilets, it all becomes part of the same thing.

To me, the magic of Junk was that you had this esoteric music and art and clothing—a real care for knowledge and detail—but there was also a maniacal thirst for drugs and sex, which you might associate more with what you’d find in the average high street night club. It was really unusual, that combination of fastidious music obsession and it not being a place where base impulses were reined in. You know, it wasn’t Cafe Oto. I remember walking around and you’d just hear all this gossip about who’d been caught fucking in the toilets, and everyone’s eyes were bursting out of their skulls.

Rhys Webb: It was ultimately a euphoric club experience. I think mainly it was so exciting because we were 18, 19, 20 when we started it, and all the people coming down were similar ages or even younger. Everything felt as exciting and new as it did to the next person. It was that high energy kind of feeling.

Oliver Abbott: It’s funny, when you’re talking about that I can’t help but keep linking it back to when we first started going to London to [garage rock all-nighter] Mousetrap. We had a big group, obviously really young, and everyone was off their nut all the time, being swept away.

Rhys Webb: That community thing exists in all great clubs, whether it’s house music or hardcore. I think we managed to capture that same kind of community feeling. It was locally based people coming down, making their own clothes, having their own night that no one else really knew about. Everyone was just bouncing off the walls. I mean there was an element of… it’s not “exclusive,” what’s the word? It was something to be a part of, in a way.

Ciaran O’Shea: Social outcasts.

When was the first night?

September 20, 2002, and it went on until September 2006. We did about 43 parties in that time and had a fucking blast. But Southend High Street back then could be a fucking war zone. You’d run a gauntlet, there’d be people trying to fight you. I think that probably contributed towards that sense of release and relief and a surrender to, ‘Well, I ain’t fucking going back out there…’

Like a weird version of the Blitz spirit, where there’s a war going on outside. How much was Junk a conscious attempt to define yourselves against the mainstream culture of that time? And how much aggro was there from bother boys trying to start fights?

Oliver Abbott: That’s the funny thing, you’d get people wandering in and I think they’d actually enjoy it. I used to get people coming up, asking to have a go on the mic and that. I don’t think there was any actual trouble inside, they enjoyed the oddness of it.

Ciaran O’Shea: The doormen weren’t afraid of slinging someone out or stopping someone going in. Even if I was playing records I’d join the queue and chat to people outside, it was a kind of club night in its own right. People would wander past gawking at these weird and wonderful people. I remember getting to the front once and the guy on the door was like, “I wouldn’t go in there, mate, it’s full of queers.” I was like mate, come on.

Rhys Webb: I can definitely remember gangs of people surfing around us, not in a threatening way but literally mouth open, just like, ‘What the hell’s going on here?’ Everyone did look amazing. People would buy old school shirts, cut them up, spray paint them, and just make an outfit for the night. I think Karen O was a big inspiration. Crazy 80s ball gowns.

Dean Chalkley: Leotards. Fingerless gloves.

Rhys Webb: There was this great gang that used to come down led by a girl called Bianca, who used to cover her face in green paint. Ciaran’s graphics and artwork represented that energy as well. If you saw his flyers tomorrow, it would still look like a club you’d want to go to. It very quickly had its own very strong aesthetic.

The visual side of it was so impressive. I had Ciaran’s flyers on the walls of my bedroom in university halls and I remember Dean’s photos being in style magazines all around the world. I went with a girlfriend once and you took her picture but not mine. That crushing disappointment aside, it was incredible how this small scene in Southend traveled, and it felt like Junk existed in a sweet spot in history where people were just starting to figure out how to present themselves online but weren’t too self-aware to have fun.

It wasn’t really an internet thing, although we were on MySpace and stuff. I guess it’s crazy that it did reach people internationally. There were people in Italy, New York; I’ve met people over the years who had pictures from the night on their walls even though they never once made it to the actual club, including people from all over the UK who were too young to get there.

Dean Chalkley: I did a story for NME but it wasn’t commissioned, I just showed the picture editor Marian Patterson and she said ‘Can we run this?’ Even someone who’d never known anything about it was immediately like, ‘I wanna be there.’ Like all the other great clubs through history, the moons were all in alignment—there was the music, the people, the fashion, and the attitude. It was almost a collective individualism that magnetized people together against all the odds in that unlikely place for an amount of time. It was a portal to somewhere else.

Rhys Webb: There was never a night you didn’t have butterflies in your stomach.

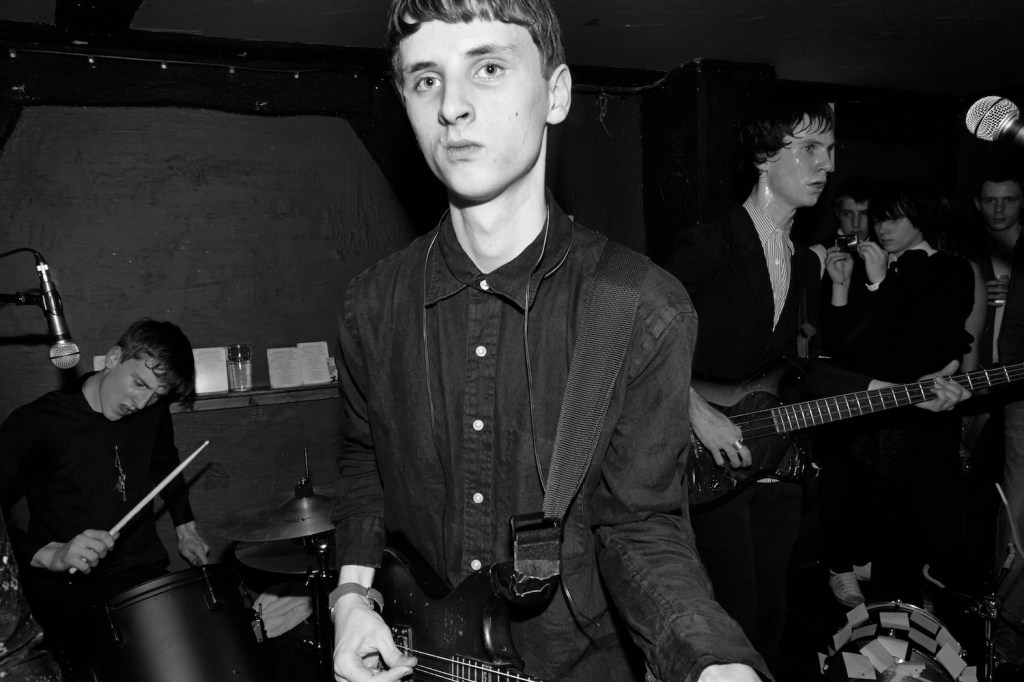

It’s interesting that we’re 40 minutes in and we haven’t talked about a single band that played yet. If anyone does an interview about CBGBs or whatever the first thing they talk about is Debbie Harry or the Ramones.

Dean Chalkley: You had great bands as well, didn’t you—No Bra…

There’s one question that’s always bugged me: Why did the Xerox Teens replace their rhythm section? Cos it was fucking banging. The little rabbit drummer man and then the bass player with the handlebar mustache and string vest.

Ciaran O’Shea: Maybe it was a request from the photocopying company. I think there were about 11 or 12 parties with bands, out of the 40 odd we did, but they were very potent—we had the Junk Musical type affairs where we’d take over the whole three floors of the Royal Hotel. There’d be 600 kids in there. There was Neil’s Children, who became the de facto house band—it was so violent and energetic and exciting to watch.

Rhys Webb: The Violets were great, a cold, gothy Banshees style group featuring Joe Daniel, who set up Angular Records at that time, which signed Klaxons for their first single. We used to do weekenders as well, which is another influence from the soul scene. A band called The Rotters played one of them and Faris Badwan was their drummer at the time. [Badwan quickly progressed to becoming lead singer in The Horrors.]

Ipso Facto, I saw there.

Rhys Webb: Twisted Charm we had there.

Ciaran O’Shea: Errorplains.

Dean Chalkley: Rhys, with The Horrors and These New Puritans, did those bands start up quite quickly [after Junk began]?

Rhys Webb: Josh [Hayward, Horrors guitarist] was DJing at [London indie disco mainstay] White Heat and so was Faris, and we all soon became a close bunch of mates. We had our first rehearsal a week after deciding to form the band, we went straight there after a Junk event on no sleep—Joe [Spurgeon] was wasted, he fell off his drum stool backwards while we were playing—and then played our first show a week after that. Then we didn’t stop for ten years.

It worked out pretty well. Are there any ‘ace-faces’ from Junk that you wanna shout out?

Ciaran O’Shea: Maximum respect to Lynn the barmaid, who was integral in every one of those parties and would run the bar single-handedly. She was a former Marine who transitioned from male to female. Tough as nails: a speaker fell off the wall once while people were dancing, and Lynn was out there holding the speaker up, angle grinder in one hand, sparks flying into dancers as she fixed it. I asked if she needed a hand. She just turned and said, ‘Do I look like I need a fucking hand?’

Oliver Abbott: She once fixed the mixer with a soldering iron. Wasn’t she a world champion paintballer as well?

Ciaran O’Shea: No, it was Laser Quest. There was Richard that ran The Royal Hotel as well, who you’d see around town in his Jamaican string vest and battered red Ferrari.

Rhys Webb: Our friend Brad Steptoe was doing his band Wretched Replica, too. They were all just amazing people, with amazing style and amazing clothes.

Ciaran O’Shea: People were customizing clothes they’d bought from Paul’s Discount clothing or the Army and Navy shop on the high street and it got to the point where Hedi Slimane, who was head of Christian Dior menswear at the time, came down, snapped up all the young kids, and took them out to Paris for a men’s catwalk show. These New Puritans [who played Junk and regularly attended] wrote the soundtrack for that Dior show. It was an insane time.

How did it feel when the eyes of the world kind of turned towards you?

You mean when the commercial bomber had us in its sights?

Rhys Webb: We enjoyed every minute, really.

Oliver Abbott: It was amazing getting more write ups but personally I don’t really remember anything changing.

Ciaran O’Shea: You could tell that word was spreading. You started seeing people who didn’t look like Southend rats.

Dean Chalkley: One thing that was definitely a moment for me was when I came out of the tube one day at Oxford Street and Topshop used to be over the road. I looked over there and I was like, ‘They’ve got The Horrors in the window.’ It felt like it had flipped right out from this Southend basement into the wider world as this kind of big, bulging monster from Akira or something.

Rhys Webb: There were literally pieces in the collection that had just been lifted from Faris’s shirt. We’d go to places like Leeds, and there’d be boys and girls in eyeliner with their hair standing on end, in polka dot shirts and waistcoats and black scarves. People were dressing like that everywhere really.

Ciaran O’Shea: I remember going in Debenhams department store once and they had a clothing range called ‘Junk Deluxe’ and it was basically this black T-shirt with one of my flyers printed on it. I just thought, “Who the fuck is doing this, man?”

“I remember Junk’s last night… being so fucked on pills that I was puking into my hands whilst we were playing the records. I was loving every second of it”

Can I drill you for some debauched stories from the Junk days?

Rhys Webb: I remember on the last night we did, standing behind the decks with Ollie, playing our last few tunes, and being so fucked on pills that I was puking into my hands whilst we were playing the records. I was loving every second of it; I wasn’t gonna move anywhere. It was a puke of love.

Oliver Abbott: I don’t know what I’d taken, but I was halfway through my set when it kicked in and I was too petrified to play records, so I hid behind the decks and had to pass Ciaran the records I wanted him to play. I was too terrified of leaving my safe space.

Rhys Webb: I remember an afterparty round mine and my mum came back with my brother and sister in the morning. Everyone was still up and Ollie was passed out wearing a motorcycle helmet in the middle of the floor. My mum just stepped over him and said, “Morning, Oliver.”

Oliver Abbott: She was cooking Sunday dinner around me when I suddenly came to. The ones we had in my flat in Leigh were really good because it was above a shop, so it used to be fucking carnage up there. I was really strict so if I didn’t know someone, they’d have to spend eight hours in a car while their mates were up in the flat.

Ciaran O’Shea: Remember that geezer who turned up who hadn’t been to Junk and he was telling us about his machine guns? He disappeared and came back with two or three decommissioned World War II machine guns. Oliver had a “war room” at the back of his flat, and we all got dressed up in military outfits and posed with these machine guns. He left on Sunday afternoon and someone had to shout down to him from the balcony that he’d left them behind.

Was Junk busy from the start or was the first night a quieter affair?

Oliver Abbott: I remember the first night really well. There wasn’t much electronic stuff then, it was mainly punk and Detroit garage rock stuff. We didn’t expect anything from it, and it was a massive, massive shock. It’s one of my favorite memories in the world: We finished, and we were counting all the money, and we were throwing it up in the air so it all rained down on us. It wasn’t some contrived money-making scheme. It’s almost like there were a few too many people to have back to someone’s house so people needed somewhere to go.

Do you think Junk could have happened anywhere other than Southend?

All: No.

Dean Chalkley: It certainly had its imitators, even in Southend.

I have to be careful when I ask this question, but to my mind, there’s not really been anything in the UK since Junk that’s quite had that same potent mix of all the component pieces that we’ve spoken about. Do you have any ideas as to why?

Ciaran O’Shea: I think to a certain extent of the anonymity that comes from living in that time before… if you were unlucky, someone might take a fucking Polaroid of you or a photo on one of those primitive early camera phones. We were very lucky to have Dean down there from 2003 beautifully capturing these moments, but other than that, man, there’s not loads of footage. It was a time when you could go down there, cut loose and fucking enjoy yourself and not be kind of scarred the next day by the evidence.

How did it end?

It was quite nice to have control over that. We held a funeral for Junk, people turned up dressed in black with flowers, someone was playing the trumpet with his shirt off.

Dean Chalkley: What I think is really beautiful about it all is that we’re all evangelists. We love this music and we wanna make everyone listen to it, and to this day, we’re all still doing that. There’s an energy that transmits when you’re finding your own culture and making your way through the world.

RATS: Confessions of a Teenage Junkie, a special event celebrating Junk Club, takes place at the Beecroft Gallery in Southend on Saturday, October 4. It runs from 5PM till 8PM, featuring a short film, booze, a musical performance from a secret special guest, and a live Q&A featuring all of the people interviewed above plus Vanessa Roberts (She Set, Sect Club). Tickets are available here.

The post A Brisk Oral History of Junk, the UK’s Last Great Club Night appeared first on VICE.