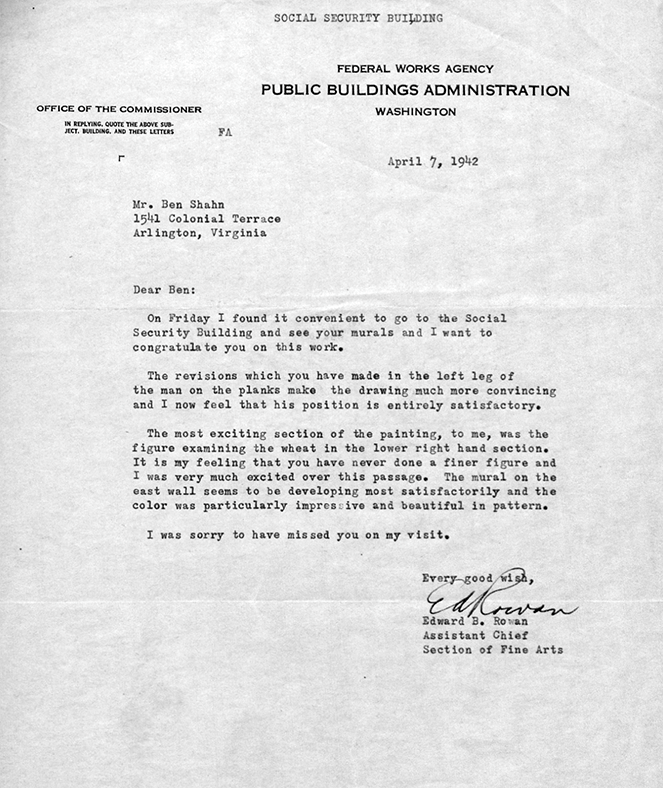

In April 1942, Edward B. Rowan, the assistant chief for fine arts at President Franklin Roosevelt’s Public Buildings Administration, wrote the painter Ben Shahn about some frescoes Shahn was creating for a new federal office building in Washington, D.C. “On Friday I found it convenient to go to the Social Security Building and see your murals,” Rowan wrote:

And I want to congratulate you on this work…. The most exciting section of the painting, to me, was the figure examining the wheat in the lower right hand section. It is my feeling that you have never done a finer figure and I was very much excited over this passage. The mural on the east wall seems to be developing most satisfactorily and the color was particularly impressive and beautiful in pattern.

This fan letter was one of several historic documents, most of them technical, collected by the Smithsonian four years ago to celebrate the 80th anniversary of an art work that could be rubble this time next year—if not sooner. The Social Security Building, which is now called the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building, is on a list of 45 buildings designated by the General Services Administration for “accelerated disposition” in 2025. Employees of Voice of America, the agency that resides there, received notices last Friday that they will soon vacate the building, and on Wednesday the Trump administration sped up that process by using the government shutdown as an excuse to furlough them all.

In addition to the Shahn frescoes, the Cohen building contains distinguished New Deal murals by Philip Guston and (I neglected to mention in an earlier post) Seymour Fogel and the ironically named Ethel and Jenne Magafan. Gray Brechin, founder of a nonprofit called the Living New Deal, which uses creative crowdsourcing to track the fate of New Deal art around the country, told me the Cohen building is “a kind of Sistine Chapel of the New Deal.”

If the Cohen building gets sold, Daniel Leckie, who until last winter was a member of GSA’s historic preservation team, told me, the buyer will “likely tear it down” because the cost of renovating it is too high. “The private sector can’t renovate that building in a profitable way,” Leckie said. “It’s something that only the government would be able to do.”

It’s unlikely the Cohen will sell for anything approaching its market worth. Three other buildings on GSA’s must-sell-now list are, like the Cohen, situated in Southwest D.C. (though only the Cohen was built during the New Deal). Selling all four at the same time guarantees they’ll go cheap—and that’s before we take into account that Southwest D.C.’s vacancy rate is a dispiriting 15.4 percent. (Anything above 10 percent is a problem.)

Most New Deal–era buildings in Washington are in pretty good shape. The Interior building (built in 1936) is a jewel. The Environmental Protection Agency building (built in 1934), which for years headquartered the Post Office, got spruced up a dozen years ago and was renamed for Bill Clinton. Even the Mary E. Switzer building, which sits across C Street from the Cohen building and was built at the same time and designed by the same arthictect in the same vaguely Egyptian Revival style, received an extensive renovation in 2020.

Only the Cohen building, which occupies the most enviable location of all these—facing the Mall two blocks south of the Capitol—and which contains the most significant New Deal art, was allowed, over eight decades, to deteriorate to the point where selling it off seemed plausible to Democratic and Republican legislators alike (though few know about the valuable art inside).

Why did this happen? Because a building constructed in the late 1930s for the newly created Social Security Board (now the Social Security Administration) suffered the misfortune of never actually housing the Social Security Administration. On its completion it was requisitioned by the War Production Board, and in 1954 the Voice of America moved in. That’s when its troubles began.

The problem was arithmetic. Most federal buildings (the Pentagon is an exception) are owned not by the agency situated there but by GSA, which requires the agency to pay rent. As in the private rental market, the quality with which a given federal building is maintained depends on the amount of rent the tenant pays, which in turn depends on the size of the tenant’s budget.

Social Security is the single largest item in the federal budget, responsible for 22 percent of all spending, and to administer all that spending Congress gives it about $14 billion per year. The roof will seldom, if ever, leak at Social Security’s headquarters in Woodlawn, Maryland. The U.S. Agency for Global Media, on the other hand, which includes Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and four other regional news organizations, has a budget of less than $1 billion, of which VOA must get by on less than $300 million. Consequently, the roof in the Wilbur J. Cohen building leaks pretty much all the time.

For a couple of decades, the Cabinet agency then called the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, or HEW, shared the Cohen building with VOA. HEW had (and, as the Health and Human Services department, still has) a huge budget that ought to have been sufficient to bankroll an extensive renovation of the Cohen building. But instead, HEW got Marcel Breuer to build it a Brutalist new headquarters next door, completed in 1977. (Breuer’s headquarters for the Housing and Urban Development building, incidentally, is also condemned to GSA’s accelerated disposition list.)

The Cohen was an increasingly bad fit for VOA, because the rent was too high (VOA had to pay for square footage in the building that it didn’t use) and because new technologies such as digital streaming ran afoul of the Cohen’s thick walls. So when VOA received notice from GSA in December 2020 to vacate the Cohen building by 2028, no one felt especially sorry.

Later, during the Biden administration, Amanda Bennett, chief executive of VOA parent USAGM, arranged for VOA and USAGM to lease handsome new quarters on Pennsylvania Avenue owned previously by the law firm Wilmer Hale. The savings were substantial, with annual rent going down from $24 million per year in the Cohen building to $16 million in the Wilmer Hale building. The landlord sweetened the deal with two years rent-free and two years half-price; by giving USAGM $27 million in cash to build a studio; and by supplying free of charge $10 million worth of office furniture, according to former chief financial officer Grant Turner.

But when Trump moved back into the White House, Bennett related in a March Wall Street Journal op-ed, his de facto USAGM chief Kari Lake tweeted out an attack video (retweeted by DOGE chief Elon Musk) declaring herself “horrified” by the opulence of USAGM’s new quarters, which was “costing you, the taxpayer, a fortune.” In reality, the new digs were saving the taxpayer $40 million over four years and $8 million per year thereafter. Lake quickly set about cancelling the lease.

“Here’s the kicker,” Lake said. “They already have a building that they’re located in that is paid off, that they could have renovated or updated.” Never mind that the GSA, under Lake’s boss Donald Trump, had evicted USAGM and VOA from the Cohen building. And never mind that Senator Joni “We Are All Going To Die” Ernst, Republican of Iowa, had two months earlier inserted into a water resources bill signed into law by President Joe Biden a provision to sell the Cohen building, which Ernst called “a 1.2 million square-foot monument to waste.” (Why a senator from Iowa would be in a hurry to unload a particular government building in Washington, D.C., is a mystery for another day.)

A similar cognitive dissonance pervaded an April hearing chaired by Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, held inside the Cohen building’s auditorium, with Republican members lining up to condemn as a taxpayer rip-off VOA’s new quarters and its old quarters; with Democrats seemingly unaware of the backstory; and with nobody mentioning anything about the murals, even though the Guston was situated directly behind where they sat (albeit behind a curtain).

What’s going to happen to those murals?

In my earlier entry, I wrote that nothing will prevent a private buyer of the Cohen building from demolishing these masterworks. It turns out to be a little more complicated than that. But only a little.

The GSA, it turns out, spent the previous two years preparing a report (funded by Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act) proposing a $1 billion green renovation of the Cohen building from top to bottom, to be completed by 2032. The Wilbur J. Cohen Building Feasibility Study, which is not available publicly, proposes making the Cohen building “a flagship in the federal government portfolio,” presumably for an agency with deeper pockets than VOA. To that end the study proposed, among other things, replacing an ugly parking lot in front of the building’s C Street entrance with a small park; converting one or more of its interior courtyards into enclosed atriums; constructing berms to divert flooding (climate change has altered that location from a 100-year Potomac flood risk to a 10-year risk); restoration of the Cohen’s handsome green-marble-clad corridors; and of course protection of the murals, which “add a sense of cultural identity in the building that remains from tenant to tenant.”

But before the GSA’s ambitious plan could be circulated widely, Ernst headed it off with the water resources amendment that put the Cohen building up for sale. When the Trump administration came in it deep-sixed the feasibility study and accelerated the sell-off.

Former GSA preservation expert Daniel Leckie told me that, while it’s true that under the National Historic Preservation Act a private owner can demolish a building on the National Historic Register, before the federal government sells that building it’s required to consult with preservation groups about ways “to avoid, minimize or mitigate any adverse effects” from the sale. Losing the murals definitely qualifies as an adverse effect. “GSA takes its responsibilities under the law seriously,” the agency’s press office reassured me, “and will comply with all applicable laws.” But that consultation, you won’t be astonished to hear, hasn’t happened yet, not least because DOGE fired or put on leave the historic preservation employees who would normally perform it. (Leckie was one of them.) Some of these employees are now being brought back, but it seems doubtful this process will be followed properly unless a private preservation group takes GSA to court.

In addition, according to Mary Okin, assistant director of the Living New Deal, “when a federally owned building with New Deal art is sold, the GSA retains ownership of the artwork and leases the building’s art with historic preservation requirements in place.” This principle was reaffirmed in district court last March.

“GSA has actively engaged art conservation professionals to assess the paintings,” the press office told me, “and to develop a plan to protect them, should the government proceed with disposal of the Wilbur J. Cohen Building. We are committed to working with property owners responsible for providing the care of any artwork involved in the sale or transfer of property.” While I don’t doubt GSA’s good intentions, I’m skeptical the White House will give GSA much running room. DOGE laid waste to GSA’s fine arts staff, too (though, again, some of these employees are now trickling back).

If I sound cynical about Trump’s intentions for the Shahn frescoes, the Guston, Fogel, and Magafan murals, four friezes I discussed in the earlier installment, and whatever other treasures might lie within the “Sistine Chapel of the New Deal,” I have reason. Not only does Trump routinely show contempt for the rules; he seems to harbor a particular aversion to art preservation.

Do you know the very sad story about Trump, the Metropolitan Museum Art, and Bonwit Teller? In the early 1980s, Trump pulled down the department store’s flagship on Fifth Avenue so he could erect Trump Tower in its place. The 1928 structure included limestone relief panels that the Metropolitan Museum of Art asked Trump to preserve for its collection, along with some bronze latticework. Trump agreed. But when the moment arrived, Trump decided it was too much trouble, and he had construction workers demolish them instead. The total cost to preserve the items, The New York Times reported, would have been $32,000 and approximately a week and a half of construction delays.

These were bas reliefs of lovely naked women. If Trump couldn’t be bothered to save those, what are the odds he’s willing to save murals depicting the sweat and toil of the sort of ordinary laborers he sticks it to every single day? It’s probably not too late to save the Cohen, but preservationists will have to move fast. If you’re looking for inspiration and you find yourself in New York, I recommend you take in the Jewish Museum’s excellent Ben Shahn retrospective before it closes October 26.

The post There Was a Plan to Save These New Deal Masterpieces. Then Trump Won. appeared first on New Republic.