Enter most any bookstore in America, and you’ll find them, their covers gleaming with motifs of barbed wire, electric fences, and menacing birds. Perhaps a person will be standing on a railroad tie, facing a building where the tracks ominously end. At least a few of the books will bear a familiar title: The [Blank] of Auschwitz.

Over the last decade, a multitude of mega-bestselling works of Holocaust literature have emerged. These books—mostly novels based loosely on true accounts—mimic one another, with emotionally accessible narratives of love and hope that often end on a perplexingly heartening note. Loathed by scholars and largely disregarded by mainstream book reviews, many of these titles have nonetheless gone on to sell hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of copies. Their runaway success, some scholars fear, has begun to warp the popular sense of this history, reshaping the camps as settings for redemption arcs rather than suffering and murder.

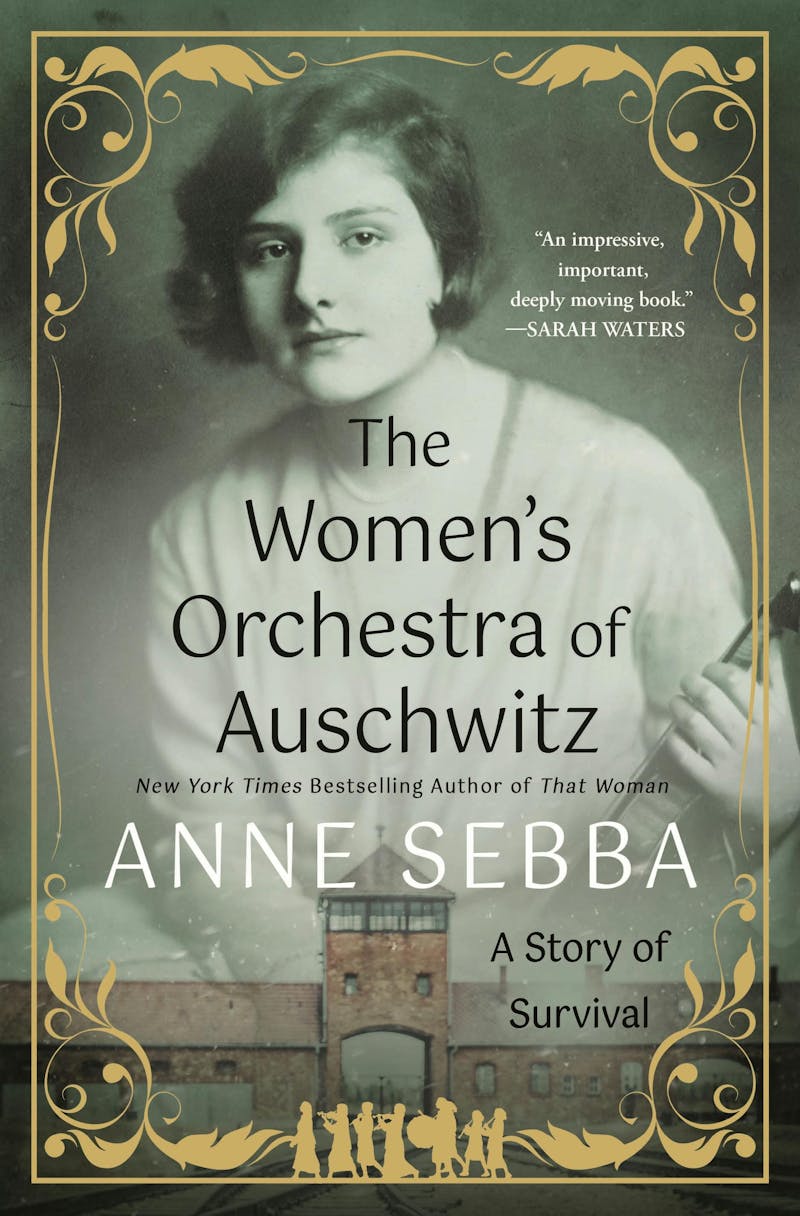

The title and cover of The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz: A Story of Survival, by noted British biographer Anne Sebba, may be a play for that market. Thankfully, Sebba mostly does not stoop to it. She recounts the story of an orchestra made up of nearly 50 women and girls from 11 countries, which was led primarily by the violinist Alma Rosé, Gustav Mahler’s niece. In spare, almost plain prose, Sebba follows the orchestra from its earliest days in 1943, when a notorious head female guard, Maria Mandl, took inspiration from the camp’s male orchestra and decided to start a women’s equivalent.

For its members, playing in the orchestra was a lifeline. Mandl arranged instruments and practice space. She issued them extra food and clothing and ensured access to slightly better medical resources. Yet the circumstances were acutely sadistic: The orchestra’s prime purpose was to play cheerful marches while the SS drove prisoners to slave labor details, or to perform concerts for guards and occasionally visiting Nazi dignitaries.

Sebba’s rendering of the musicians’ horrific situation is judicious. She approaches her subject with the sobriety it deserves and rarely indulges in cliché. Yet for all her restraint and good intent, her book propagates a frustrating distortion of the history.

For decades, scholars like Guido Fackler have studied music in the Nazi camps, demonstrating that orchestras that were set up and closely controlled by the SS were commonplace. Fackler’s research shows that in some camps—Auschwitz among them—the SS forced orchestras or ensembles to play during punishments or executions. At Birkenau, they compelled a camp orchestra to play for inmates during the so-called “selection,” the idea being to quell their fears of impending death. The survivor Erika Rothschild remembered hearing Polish, Czech, or Hungarian melodies, chosen to match the nationality of the transports.

But Fackler would quickly add that this represents just one element of the history. And while Sebba presents a sound retelling of what he and other scholars have revealed, her focus on the orchestra obscures a rich, permeating, and far more varied history of music during this time, namely that which sprang up from the prisoners themselves beyond the perverse auspices of the SS. The risk of her framing is that it erroneously places the orchestras—another tool of abuse in the Nazi arsenal—at the center of the story.

Sebba is not alone. The orchestras have already been the subject of several books—most recently in a new translation of Szymon Laks’s excellent memoir about his time as the conductor of the Auschwitz men’s orchestra—and in the popular media. In fact, there has been a boom in coverage of music in the Nazi camps in recent years, starting with a 2019 60 Minutes segment about music-making in the Nazi camps that featured Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, the last living member of the women’s orchestra, about whom Sebba also writes at length in her book. Pieces in The New Yorker, The Washington Post, Le Monde, The Guardian, and The New York Times soon followed, to name just a few. Several TV programs (the latest, in February from the BBC, also centered around Lasker-Wallfisch) have covered the orchestras. With little exception, the coverage replicates the focus on SS-sanctioned music.

To the small yet stalwart group of musicologists who have meticulously studied this topic for decades, the abundance of attention has felt cautiously gratifying. Yet it is also vexing. A few years ago, I wrote a book about Aleksander Kulisiewicz, a prisoner musician at Sachsenhausen who, after the war, created one of the most important archives on art and music in the Nazi camps, which is now housed in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. While reporting the book, I worked closely with a number of leading musicologists. One of them was Swarthmore’s Barbara Milewski. For her, the surge in interest given to the orchestras has been crucial in revealing the perfidy of Germans using culture for evil. But she bristles at the narrowness of the focus. “This is only part of the story of ‘music in the camps,’” she told me, “and certainly not the most compelling from a humanistic standpoint.”

Survivors recount the immense pain it caused them when the SS would force prisoners to sing on command. The intent was to frighten, humiliate, and degrade the prisoners.

By contrast, in many survivor memoirs, music emerges as a ubiquitous part of camp life—for better and for worse. Survivors recount the immense pain it caused them when the SS would force prisoners to sing on command: often cheerful German folk tunes, sometimes late into the night. The intent was to frighten, humiliate, and degrade the prisoners. The singing itself was physically draining—another form of SS persecution.

Sebba tells us about the torment music caused members of the orchestra—and those forced to listen to it. On marches back to the camp at the end of a day’s work, prisoners—often laden with corpses—had to listen to jaunty melodies. “We hated those musicians,” one former inmate recalls in the book. “We couldn’t keep our clogs on. It was 20 below zero … death was magnified by the orchestra.” Hélène Wiernik, a violinist in the orchestra who was just 16 upon her arrival, gave up her beloved instrument after the war ended. “She was too weak, too damaged physically,” Sebba writes. “She said she simply did not have the endurance to continue playing.”

Yet at times, her book can fall into the trap of seeing music as inherently uplifting. Many of her chapter titles, for example—“I felt sun on my face,” “She gave us hope and courage,” “The orchestra means life”—are tonally at odds with what the research in the book says. In this she also has company—The Washington Post, for instance, wrote that prisoners found “comfort, dignity and sometimes a lifeline” in music, while The New York Times described music as a “buoy” in the camps.

In reality, inmates turned to music—when they weren’t forced to do so—for myriad reasons. Uplift was just one. Some found in music entertainment, a solution to intellectual boredom, a means of escape. At every major Nazi camp, deportees of all backgrounds, many with no formal training, created and performed music. There were choirs, ensembles, troupes, duos, and individual singers performing in their blocks—and sometimes even “touring” from block to block—largely beyond the knowledge of the guards. Buchenwald had a jazz big band, Falkensee was home to a “gypsy orchestra.” Soviet POWs gathered to perform at Flossenbürg. Sachsenhausen alone had a harmonica troupe, a secret Jewish choir, and a string quartet that performed contraband scores by Beethoven, Brahms, Schumann, and Dvořák at the camp mortuary.

Prisoners often created parodies of existing tunes, in which they processed what was taking place around them, commented on it, documented it; they slung broadsides, ridiculed Hitler, and expressed their fear of Germany’s domination of Europe. After the British evacuation at Dunkirk, for instance, Kulisiewicz composed anxious lyrics about the Wehrmacht’s seemingly unstoppable advance. After their defeat at Stalingrad, he wrote jubilant lyrics of celebration.

There is an implicit disbelief that art would and could exist in a place as ghastly as a Nazi camp. Was there truly space to create amid such suffering?

Why center the orchestras when they were set up and controlled by the SS and used for sadistic purposes? In that focus, hundreds of fascinating people are overlooked. One is Krystyna Żywulska, a poet of such capability that her verses were passed around orally in Auschwitz. When they reached one so-called prominent prisoner, the woman was so moved that she arranged for Żywulska an indoor work assignment, likely saving her life. Another is Rosebery d’Arguto, a Polish-Jewish conductor who gained prominence in 1930s Berlin for his choral directing and composing. A few months after the Germans deported him to Sachsenhausen in October 1939, he formed a secret four-part choir composed of about 25 Jewish prisoners. The choir rehearsed and performed compositions d’Arguto arranged at immense risk to itself and its audience. When the SS discovered it in the fall of 1942, they soon deported d’Arguto to Dachau and most of his singers to Auschwitz.

Scholars tend to grumble about their work being popularized or misinterpreted; nuance is always lost in the process, and perhaps this is inevitable with music in the Nazi camps too. Yet in so much coverage, and even in Sebba’s book, there is also an implicit disbelief that art would and could exist in a place as ghastly as a Nazi camp. Was there truly space to create amid such suffering?

But there are endless examples of art being made in the most distressing of times, from the trench poetry of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon in World War I to artists in Gaza making art amid—and sometimes with—the rubble of their city. The German-Jewish artist Charlotte Salomon painted hundreds of remarkable gouaches while in hiding from the Gestapo in southern France, before ultimately being arrested, five months pregnant, in 1943 and murdered at Auschwitz not long after.

These examples remind us that artistic expression is always a part of the human condition. In the case of the Nazi camps, focusing on uplift, framing music as miraculous—especially in the case of the orchestras—flattens a multidimensional story that is far more interesting in all its complexity, contradiction, and variety.

The post What Place Does Concentration Camp Art Have in Holocaust History? appeared first on New Republic.