In the fall of 1983, Judd Apatow made his way down to a musty room in the basement of Syosset High School and stumbled upon his secret weapon—he just didn’t know it yet.

Apatow was 15 years old, deep into an infatuation with comedy, but had nowhere to channel it. Boyhood on Long Island was something like a John Hughes movie: idyllic on the outside and tormented on the inside. “A lot of what formed some aspects of my personality was that there was an enormous amount of sports happening and I wasn’t good—I would always choke and panic,” Apatow told me recently.

This happened, he emphasized, all the time: in gym class, at pickup games during lunch, after school. “Imagine not being very good,” he said, “and having to be picked close to last multiple times a day,” and then being given a position “so far out in right field that I was almost in the middle of Jericho Turnpike.”

The jocks may have been the kings of high school, but Apatow came to understand that theirs was a fleeting achievement. “I remember as a kid thinking, It doesn’t matter if you’re good at this,” he said. “You become suspicious of how everything works—power structures; whatever the caste systems are—and then you’re drawn to comedians who are always calling out the different parts in life that are bullshit.”

He worshipped Lenny Bruce, Steve Martin, Albert Brooks, Gilda Radner, George Carlin, Martin Short. He wanted a friend to talk about Saturday Night Live with every week, but couldn’t find one. Comedy wasn’t cool—at least not among the teenagers he knew. “People weren’t interested in it,” he said.

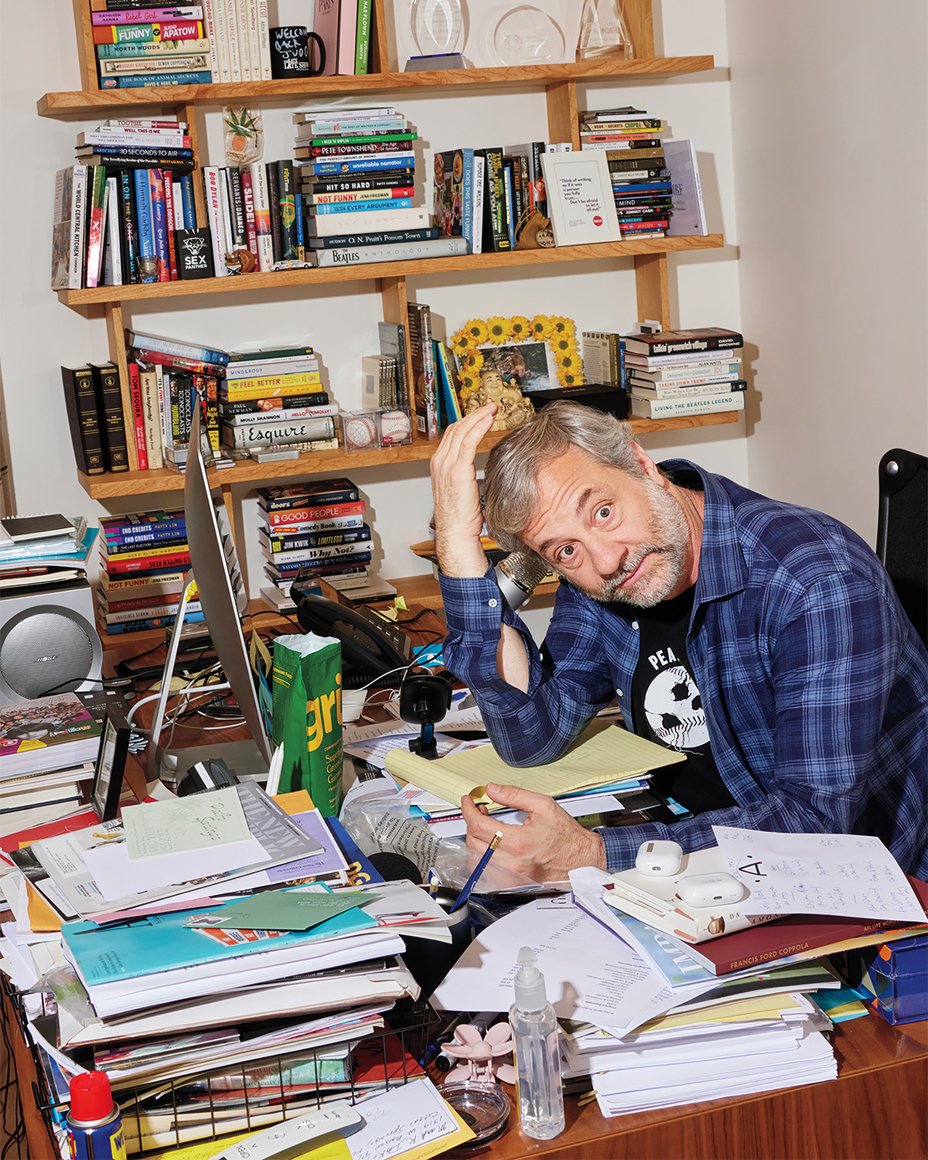

Apatow was describing all of this to me in his office in West L.A. On this particular morning, he had asked me to come by at 7:30 a.m. (Apatow is a morning person, a quality that vexes his fellow comedians.) When I arrived at 7:23, he was already outside waiting, carrying a half-eaten banana and blaring classic rock from his smartphone. Inside, we settled into a couple of chairs around the long table in his writers’ room—a writers’ room that actually has windows, he proudly pointed out—and talked about loneliness.

While his classmates were out playing baseball, he holed up in the public library, poring over microfiche of old newspapers so he could learn about Lenny Bruce’s obscenity trials. He didn’t apply the same rigor to academics. He sweet-talked his way into advanced physics, only to find himself out of his depth—he started cheating, got caught, and dropped the class. (“The teacher’s name was Richard Lesse,” Apatow told me. “So people called him Dickless.”)

But things were different at the high-school radio station. In that basement studio, he got his hands on a clunky green tape recorder that would allow him to waltz into the world of show business. WKWZ 88.5 FM was, to Apatow, a “nerd’s paradise,” though he likes to joke that the signal barely extended beyond the school parking lot. The teacher who oversaw the station, Jack DeMasi, is now nearly 80. He lovingly described WKWZ to me as a smelly “rat hole” for “misfit kids.” He remembers Apatow as an affable teen despite troubles at home. The teachers knew that his parents had gone through a hellish divorce, and that money troubles had followed.

“Judd said the scariest thing that any adviser faculty member at an FM-broadcast high-school radio station could ever hear,” DeMasi recalled. “He says, ‘I want to do a comedy show.’ ” DeMasi feared that Apatow would do a show so off-color that it would get the station shut down. “One of the things about adolescent boys is that they frequently think they’re funny, and they’re just stupid,” DeMasi said. But Apatow had something different in mind.

DeMasi had long encouraged his students to go out and talk to real people. One kid interviewed Mario Cuomo, then the governor of New York; another, R.E.M. To Apatow, this was a revelation: The tape recorder in his hand could provide a direct line to the comedians he idolized. If he could just talk to them, he could ask them how they did what they did, what it took to be funny, what their lives were like—so that maybe, one day, if he worked hard enough (though he dared not admit this to anyone), he could do it, too.

When Apatow requested interviews, he identified himself—accurately, though misleadingly—as calling from WKWZ 88.5 FM in New York. People like Garry Shandling, Jay Leno, Harry Anderson, and Steve Allen agreed to speak with him not knowing he was a teenager, only to be (mostly) charmed when they eventually found out. Apatow tells the story of walking into Jerry Seinfeld’s apartment circa 1983 and seeing the bemusement on Seinfeld’s face. “His apartment had nothing on the walls, no books in the bookshelves—he was just there to write his jokes,” Apatow recalled in his 2022 book, Sicker in the Head. “And he looked at me when I walked in like, I can’t believe I have to do this with this child.”

Apatow’s descriptions of these early interviews are laced with self-deprecation and hero worship. (Lena Dunham told me she loves them in part because his Long Island accent, which he retains, was even stronger when he was young—audience and autograph are aww-dience and aww-tograph, and he always drops the h in humor.) But when you listen closely, what you also hear is poise—and a kid trying to chart a course for his own future. In a 1984 conversation, he asks Martin Short, “How does Second City work?” and “Did you ever do stand-up comedy, like in a club?” and “Did you go to college?” In his interview with John Candy, Apatow asks how many takes it took to get the shot where Candy gets nailed in the back of the head with a racquetball in Splash. (“Three takes,” Candy responded. “I was lucky.”) Apatow then asks Candy about a rumored three-picture deal with Touchstone Films. Candy hadn’t even signed the contract yet.

Apatow told me he can’t remember how he knew to ask about that. He would hoover up information about the world of comedy anywhere he could find it. He’d hold his tape recorder to the television so he could record, play back, and transcribe SNL sketches in an attempt to figure out what made them funny. Apatow was so obsessed, so focused on doing whatever it took to enter that world, that it wasn’t until much later that he thought to ask himself, Why comedy?

If you’ve never bombed—and I mean really bombed, bombed so badly that the crickets hear crickets—you can’t possibly know what it feels like to have a room turn on you. There are two kinds of dying onstage, both painful: The first is the quiet kind, where nobody laughs. Then there’s the loud kind, where the audience openly ridicules you. Apatow has experienced both.

While he was doing his interviews for WKWZ, Apatow was also spending as much time in comedy clubs as he possibly could. He took a job as a dishwasher at the East Side Comedy Club a couple of towns over, only to realize that he couldn’t hear the comedians onstage when he was stuck in the kitchen. (He switched to busboy.) Once in a while, Eddie Murphy, still in his early 20s, would drop by to try out new material. Apatow tells the story of a time Murphy showed up, got heckled, and quickly shot back, “I don’t care what you say, because I’m 21, I’m Black, and I have a bigger dick than you.”

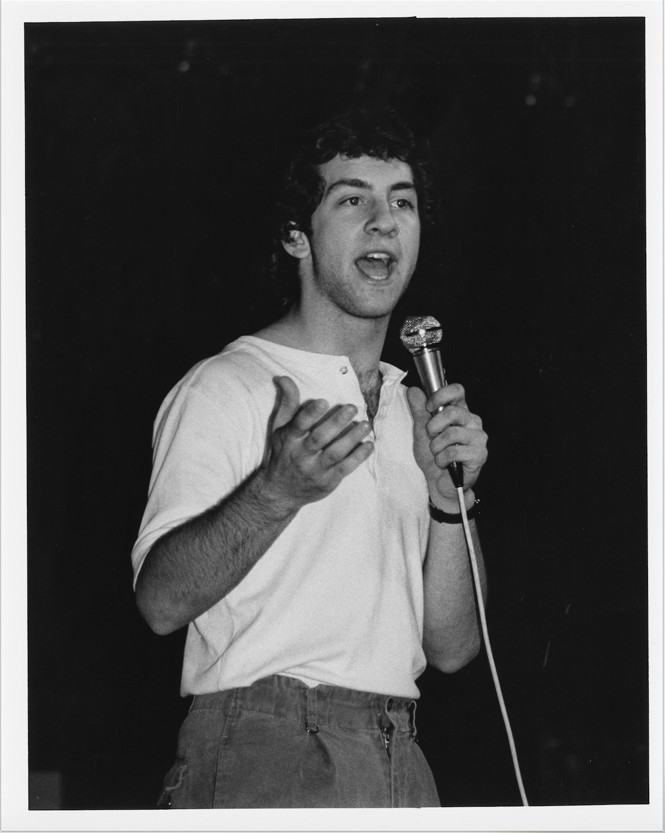

This exchange might have been on Apatow’s mind the first time he ever did stand-up, when he was 17, at Chuckles, a comedy club also on Long Island. “I had thought about getting onstage for a really long time, and was really scared,” Apatow told me. “I didn’t have a cocky attitude about it. I was shitting a brick.” He had been offered a five-minute slot late at night, typical for a rookie, and brought his best friends, Ronnie and Kevin, along for moral support. Somewhere in those five minutes, Apatow floated an idea to the audience: I’m just starting out and I don’t know how to handle hecklers, so help me out by heckling me.

This was deranged. The local scene at the time was marked by an affection for a particularly brutal form of insult comedy—Don Rickles, only meaner. Comedians mercilessly mocked their audiences, and audiences liked to punch back. Apatow was not prepared for what he had unleashed. People were shouting “You suck!” and “Get the fuck off the stage!” It got so bad that Ronnie and Kevin turned around and started threatening the hecklers. Apatow can still remember hearing their voices: You better shut up or I’ll kick your ass. “They were trying to calm the room down for me,” Apatow said. “Unsuccessfully.”

Apatow is not proud of his early stand-up. Some of the material is still funny 40 years later—a joke about his back hair getting so long that he can see it in his shadow—but much of it was a product of its time. “I don’t even know what I was thinking, to tell the truth. I’m embarrassed that I was even out there, and I hope no one remembers any of it,” he told me. One recurring bit involved jamming the palm of his hand into his eye socket, something he referred to as “the eye fart.”

There would be other bad sets, but none as disastrous as that first night at Chuckles. From then on, Apatow kept a line in his back pocket for when a set started to sour: “The great Jerry Lewis said you learn nothing by being funny. You only learn by not being funny. And I have gotten a college education here tonight. Thank you.” That actually worked. The line would always bring the audience back around “no matter how bad I bombed,” he said.

After Apatow graduated from Syosset, he went to the University of Southern California to study filmmaking. When he got there, he was startled to learn that his classmates “had been watching Truffaut and Godard at home, and I’m watching Abbott and Costello.” One classmate, Matt Reeves, went on to direct movies such as Cloverfield and the forthcoming Batman II. “His films were so good, and I showed mine and I just felt like such a fool,” Apatow said.

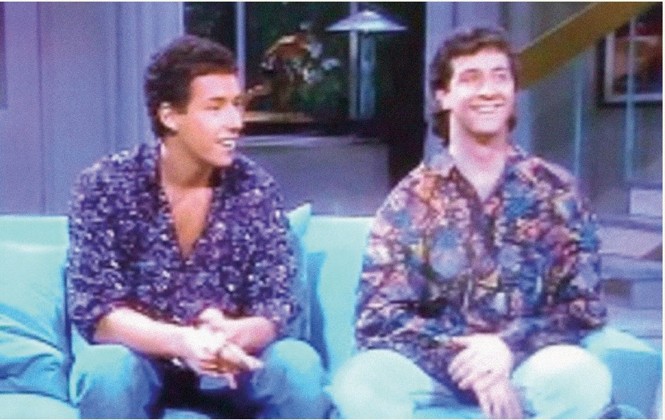

Sophomore year he landed a spot on The Dating Game, a quiz show that involved competing against two other young men for the affections of a bachelorette who had to choose a winner without laying eyes on the contestants. As Bachelor No. 1, Apatow—all dressed up in a blazer and tie—looked like a lost uncle from Full House going for a job interview. But he was in his element, making fart noises (with his hands this time, not his eye) and generally hamming it up in a charming way. When he won the competition, and the trip to Acapulco that came with it, he took it as a sign. He was already behind on tuition payments, and was so focused on doing stand-up that he wasn’t finishing his assignments. It was either final exams or Mexico. He decided to drop out.

“I was young and so stupid,” Apatow said. “All those decisions didn’t make any sense, and I had no one to discuss them with. I don’t think I debated these moves with my parents or any friend. I had no mentor. I just was an idiot who was like, I don’t want to miss this Acapulco vacation.” He also felt that his Dating Game victory was validation that he could make it in Hollywood. It amuses him now to think of how naive that was, but at the time he really thought, “This is show business.” If he could make it on The Dating Game, maybe he could make it big.

The trip to Acapulco was “terrible”: He got sunburned on the first day, forcing him to spend the whole next day in the hotel room. And it was immediately clear that there would be no actual love connection with the bubbly, blond bachelorette. (“I’ve seen her Instagram lately, and it seems like she’s had a very happy life,” he told me.) Looking back, Apatow thinks his parents were as relieved as he was to lose the tuition pressure. Nobody even feigned an attempt to persuade him to stay in school.

His grandmother lived in Los Angeles, and after he dropped out, Apatow slept on her couch for two years, toiling away at open mics and emcee gigs, where he met a couple of unknowns named Adam Sandler and Jim Carrey. (Apatow became roommates with Sandler and introduced Carrey to his manager.)

It was around this time that he hunted down the complete scripts for 42 episodes of Taxi, the classic James L. Brooks sitcom. “I would sit and outline them and study them, and I figured out that there were common structures in them,” he said. “I could see how these shows were made.” He was also spending a lot of time at the Ranch, a nickname given to the group house where a bunch of aspiring actors and comedians lived, way out in the Valley, where rent was far cheaper than it was in Hollywood. At the Ranch, he was exposed to a different breed of comedian—not the exuberant, sharp-elbowed Jews of his Long Island comedy-club upbringing, but midwesterners who were, in his telling, just as funny in a softer way.

Apatow also started writing jokes for other comedians, something he had learned was possible from the director and actor Harold Ramis, whom Apatow had interviewed back in high school. (Ramis, whom Apatow adored for Caddyshack and Stripes, had told him he’d written jokes for Rodney Dangerfield.)

Apatow was emceeing comedy shows at the Comedy & Magic Club, in Hermosa Beach. “That’s how I met a lot of my heroes,” he recalled. One of those heroes was Garry Shandling. When Shandling was doing a set one night, Apatow’s manager floated the idea to Shandling that Apatow should write some jokes for him. Shandling didn’t seem remotely interested; they had “no connection whatsoever” that night, Apatow said. But a few months later, out of the blue, he called to see if Apatow wanted to help him write a few jokes for his upcoming gig hosting the 1990 Grammys. The answer was Yes, God yes, of course yes.

Apatow stayed up all night and gave Shandling, to his surprise, a list of 100 jokes to choose from. Shandling rewrote every punch line—which, to those who knew Shandling, says more about him than it does about Apatow. The way Apatow tells it today is that they made a good team: Apatow knew way more about music, and Shandling was simply funnier. This was the beginning of one of the most important relationships in Apatow’s life.

One of Shandling’s friends, the actor-writer-director Albert Brooks, told me he remembers hanging out at Shandling’s house in the early ’90s when Apatow started coming around. “He was like Garry’s shadow,” Brooks said. “What I’ve always loved about Judd is that more than anyone, he’s a comedy savant. I would describe him as a human Friars Club. And I love that about him. Because he didn’t just love it; he knew everything. And he was funny! It was like, Who is this kid? ”

The more time Apatow spent around comedians and writers in L.A., the more he began to think he wanted to be in comedy—but not as a stand-up. “I was such a fan that I was very aware of how good people were,” Apatow told me. “I knew how funny Andy Dick was and Ben Stiller was and Jim Carrey was.” Walking away from stand-up, “there was probably a little part of me that died,” Apatow said, but it made space for something new, too.

In 1990, he and Stiller created The Ben Stiller Show, which appeared on MTV (and later Fox), and starred up-and-comers such as Andy Dick, Janeane Garofalo, and Bob Odenkirk. It produced sketches beloved by comedy nerds—see: “Legends of Springsteen”—but was barely given a chance to take off. (The show won an Emmy for outstanding writing just after it was canceled.) Furious, Apatow took a trip to Hawai‘i to wallow in the tropics, and by some cosmic turn of fate ran into Shandling near the hotel where Apatow was staying.

Shandling coached him on how to cope with the cancellation, and offered him a job writing for a series he was developing for HBO called The Larry Sanders Show. “Garry said writing is a way to figure out who you are,” Apatow told me. “It’s all about self-exploration. I didn’t think that. I just thought I was writing a funny wife joke for Rodney Dangerfield. I didn’t think spiritually about any of it. It was like, comedy is about knowing yourself? What? I thought it was just punching the horse in Blazing Saddles.” It wasn’t until then that he felt “some sort of calling” to write.

For the next several years, Apatow worked obsessively, toggling between writing gigs for the animated series The Critic and The Larry Sanders Show. Set behind the scenes at a Johnny Carson–style late-night show and featuring a parade of A-list comedian guest stars, The Larry Sanders Show was beloved by critics and industry insiders. It launched the careers of numerous comedians, and pioneered a documentary-style format that influenced shows such as Curb Your Enthusiasm, The Office, 30 Rock, and Parks and Recreation. Apatow parlayed that success into writing the 1995 film Heavyweights and producing The Cable Guy, starring Jim Carrey, in 1996. Both flopped but have since achieved cult status. This dynamic would become excruciatingly familiar to Apatow: splashy failures on projects that only grew more beloved over time.

During casting for The Cable Guy, a young actor named Leslie Mann came in to audition for the female lead, and Apatow read Carrey’s part with her. He remembers leaning over to Stiller and saying something to the effect of I can’t believe the future Mrs. Apatow just walked into the room. (The encounter was not as indelible for Mann. She doesn’t remember it at all, she told Vanity Fair years later. “Is that bad?”) By the summer of 1997, they were married. Later that year, they had their first child together—a girl named Maude. Another girl, Iris, followed.

When Maude was still a toddler, one of Apatow’s friends from the Ranch, the actor and director Paul Feig, proposed making something together. “He literally handed me a manila envelope with Freaks and Geeks in it,” Apatow said. He was astonished by what he read. He ended up developing and executive-producing the show. Around this time, the teen drama Dawson’s Creek was an enormous hit. Apatow and Feig wanted to make something that was nothing like it.

Freaks and Geeks was unusual in a number of ways. Feig and Apatow cast actors who looked like real kids, rather than finding Hollywood-ready teens grown in a lab to appear on the cover of Tiger Beat, and the characters those actors played were complex, not mere vessels for sexual objectification or moral lessons that could be neatly resolved in 22 minutes. Freaks and Geeks also collapsed the distance between pain and humor in a way that made it feel true: Going through puberty isn’t just terrible and awkward; it’s hilariously terrible and awkward.

Apatow and Feig infused the show with their own adolescent agony. The gut punch of Apatow’s life was when his parents got divorced while he was in middle school. The split was beyond ugly; it scattered the family. His brother moved in with his grandparents in California. His sister lived with his mom. Apatow lived with his dad.

One by one, all of Apatow’s friends’ parents got divorced too. They talked about divorce constantly with one another, but barely with their own parents. (Apatow’s father once left a book out on the coffee table called Growing Up Divorced but never said a word about it.) Apatow remembers he and his friends thinking, “We can’t listen to these people. They don’t know what the hell they’re doing.”

That feeling gave rise to the conviction that he had to learn to take care of himself—through comedy. “I built this obsession that I thought would free me at some point,” Apatow told me. “I had a very clear thought my whole childhood, which was: This will pay off. One day, people will be interested in this. It’s almost maniacal.”

In one of our conversations, Apatow brought up the episode in which one of the geeks of Freaks and Geeks, Neal Schweiber (played by Samm Levine), confronts his philandering father by telling hostile jokes about him through a ventriloquist puppet. “I really related to that,” Apatow said. “There was a moment where I thought, I need to learn how to juggle fire and perform at birthday parties—that desire to get a skill because you’re so traumatized by what’s happening in the house.”

One of Apatow’s closest friends, the comedian Pete Holmes, told me that he always saw Apatow as another of the geeks, Bill Haverchuck (Martin Starr). In one of the series’ unforgettable scenes, Haverchuck comes home from school to an empty house, makes himself a grilled-cheese sandwich and pours a tall glass of milk, pulls out the TV table, and dissolves into laughter watching Shandling do stand-up while the Who’s “I’m One” plays over the scene. That “raised-by-television latchkey thing,” Holmes told me, “that’s Judd. That’s all you need to know about Judd.” He went on: “It’s an isolated fan who used his love of comedy to make himself not isolated.”

Today, Freaks and Geeks routinely shows up on critics’ lists of the best shows ever made. But NBC canceled it after just 12 episodes, citing low ratings. Apatow was devastated, again.

It was around this time that he began having serious panic attacks. The worst of them happened during a meeting with Lorne Michaels at the Beverly Hills Hotel’s Polo Lounge. “We were seated in a round booth I couldn’t easily escape from,” he told me. Apatow sat in silence, screaming on the inside and wondering if he would have to fabricate a story about food poisoning to get out of the room. (“I made it through. No once seemed to notice.”)

Even when Apatow’s not panicking, his mind tends to race. He remembers sitting and watching The Merv Griffin Show as a child, tapping his toes constantly, counting the syllables of the words being said on TV. He is not prone to catastrophizing so much as compulsively planning ahead. Over the years he’s developed tactics for staying calm, first by white-knuckling it through episodes of panic and later with obscene amounts of therapy and mountains of self-help books.

After Freaks and Geeks was canceled, Apatow focused on finishing the series, even though he knew it wouldn’t be renewed. He wanted to do right by the cast of young actors, which included Seth Rogen, Busy Philipps, Linda Cardellini, Jason Segel, and James Franco, all of whom eventually became stars. Working with all of that nascent talent on one show was “like discovering a music scene,” Apatow told me. “It was like discovering Seattle or Manchester.” He told himself that if he could finish the show and know that, just once, he had gotten something exactly right, it would be enough. In the end, NBC never even aired the complete series—three of the show’s 18 episodes reached audiences only when Fox Family reran the series later that year.

In a clever act of desperation, Apatow used the show’s website to ask fans for help demanding that Freaks and Geeks be released on DVD, something that never happened for a canceled show, and which ultimately helped Freaks and Geeks find its audience.

But when the same experience happened—“almost beat for beat”—with the cancellation of his 2001 television show, Undeclared, Apatow was livid. That same year, he filmed a pilot for North Hollywood, starring Segel with the up-and-comers Amy Poehler, January Jones, and Kevin Hart, which got scrapped before it even aired. “That became the fuel,” he told me. He just kept thinking, “You’re wrong. I think all these people are great. All these writers and directors are so strong. Let’s just try to prove everybody wrong.”

When Undeclared was canceled, Time magazine had just named it one of the 10 best television shows that year. Apatow sent a framed copy of the article to the chair of the Fox Television Entertainment Group, who also happened to be the man who had canceled The Ben Stiller Show. The note said: “I don’t know if you just fucked me in the ass again or you just never took it out in 1992. Merry Christmas, Judd.”

The people who know Apatow best will tell you that his willingness to burn bridges is legendary in comic circles. “Just really tough with studio executives—like, You need to let us make this show what it is,” the comedian Mike Birbiglia told me. He went on: “When you’re in show business long enough, you start to see that there are people who are rooting for themselves, and then there are people who are rooting for the art form at large. He’s the quintessential example of ‘He’s rooting for the art form at large.’ ”

Daley in Freaks and Geeks; Jonah Hill, Michael Cera, and Christopher Mintz-Plasse in Superbad; Matthew Broderick and Jim Carrey in The Cable Guy. (Universal Studios Licensing; Courtesy of Judd Apatow; Gabe Sachs; Cinematic Collection / Alamy; AJ pics / Alamy)

Apatow can also be impressively petty. Some of the same friends who expressed to me their undying loyalty to Apatow described him as sometimes “defensive” and “biting,” the kind of person you have to work to win over. He once got into a prolonged email argument with the television producer Mark Brazill that was so over-the-top, Harper’s ended up publishing the entire thing. Brazill signed off one email to Apatow with “Get cancer,” and another with “Die in a fiery accident and taste your own blood.” Apatow, ever the comedy savant, accused Brazill of stealing the “taste your own blood” line from Sam Kinison’s 1986 album, Louder Than Hell : “That’s a Sam Kinison line you stupid fuck!!!! Hypocrite!!!! J’accuse!!!!”

Yet Apatow described himself to me as someone who wants to be liked and who tries to avoid conflict. He worries about upsetting people. “Comedians are sensitive,” he said. “Comedians are aware of all the dynamics that are happening, and they’re feelers.” The only time in all of our many hours of conversations that he ever balked was when I asked him whom he considers his closest friends. “You want me to list them?” He was horrified by the idea of making anyone feel bad.

Apatow has, over time, mellowed out. One of the people who has seen this up close is Seth Rogen, who was an unknown 16-year-old when Apatow cast him in Freaks and Geeks. “He was the first boss I ever had,” Rogen told me. He was terrified of Apatow at the time, and desperate to impress him. After Freaks, Apatow asked Rogen to be a writer on Undeclared.

The first movie they made together was The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Apatow’s 2005 directorial debut and a blockbuster. Rogen remembers the moment Apatow came up with one of the scenes that drew the biggest laughs in the film, in which Steve Carell’s character awkwardly tries to relieve himself while aroused. It is “forever tattooed in my mind,” he told me. They’d been working on the script and Apatow left to pace around, get coffee. When he returned, “he was laughing so hard,” Rogen said, and he went on to describe the whole scene, with Carell’s character having to “tilt down” to pee. Rogen lost it too. “We were laughing so hard,” he said. He kept thinking, “They would have never let us do that on television.” (Apatow told me that coming up with a joke that perfect feels like you’ve “finally connected to God.”)

Apatow made the jump to directing films at precisely the right moment. Studio executives had realized that audiences actually loved big comedic films starring actors who weren’t traditional leading-man material. Will Ferrell, who in 2003 successfully leaped from SNL to the big screen with the Todd Phillips hit Old School, was a catalyst for the golden decade of big comedies that followed.

Apatow’s success, when it came, hit like a tsunami. It is difficult to overstate his influence on American comedy. Critics started using the ungainly term Apatowian to describe his imitators.

Knocked Up was an even bigger hit than The 40-Year-Old Virgin, grossing nearly $220 million on a $30 million budget. The film told the story of an underachieving stoner (Rogen) and an ambitious TV reporter (Katherine Heigl) who, after their one-night stand results in pregnancy, must navigate the complexities of becoming parents while getting to know each other. It was raunchy, tender, absurd, and hilarious.

Apatow had worried that Knocked Up wouldn’t come together at all because he couldn’t figure out the casting. Eighty women had read for the lead part, and none of them clicked until Heigl showed up. When you find the right person for a role, “you almost feel relief,” he told me. “Because when people read it and they’re not right for the part, the scene doesn’t work. So you’re watching your scene not work over and over again.”

Heigl may have been perfect for the part in Apatow’s eyes, but she criticized the movie after it came out, touching off a larger debate about Apatow’s work at the time. She called Knocked Up “a little sexist,” and described the women characters he had written—including her own—as “shrews” who were “humorless and uptight.” (Apatow, clearly bruised, reacted by calling her choice of the word shrew something out of the 1600s.) To him, the argument was unfair. He is interested in flawed characters and what they have to do to become good people, a theme that runs through his work going back to Freaks and Geeks.

Amy Schumer told me she never understood people who dismiss Apatow’s work as sexist. The men in Knocked Up don’t seem to understand what the women in their lives are going through. Seen one way, that’s evidence of sexism; seen another, it’s an honest portrayal of how some men behave in their relationships. The subject seemed to exasperate Schumer: “His house is all girls, his cats are girls, he made the show Girls, he made my movie.” I will confess that I find the debate somewhat tiresome myself. Sometimes the flawed characters Apatow focuses on are men; sometimes they’re women. As Schumer noted, he guided her and Dunham toward realizing their own creative visions for Trainwreck and Girls, respectively.

Apatow has filmed almost all of his movies in Los Angeles because he didn’t want to be away from his family, especially when the girls were little, and he famously casts Mann and his daughters in his movies (Knocked Up, Funny People, This Is 40 ). This has provoked inevitable eye-rolling about nepotism, but Mann is a comedic star in her own right. She is the first person who reads his scripts. “She has come up with some of the great moments and scenes in all of the movies we’ve collaborated on,” he told me.

The Apatow girls—both now in their 20s, both actors—first appeared on-screen when they still had their baby teeth. Apatow likes to point out, swelling with pride, that then-8-year-old Maude completely improvised her character’s hilarious explanation of where babies come from in Knocked Up. “I think a stork, he drops it down, and then a hole goes in your body, and there’s blood everywhere, coming out of your head, and then you push your belly button, and then your butt falls off, and then you hold your butt, and you have to dig, and you find a little baby.” Mann’s character deadpans in response: “That’s exactly right.”

After a long pause, Apatow started doing stand-up again about a decade ago, and has been doing it ever since. One of his regular venues is Largo, a gem of a comedy club in West Hollywood with the prettiest twinkle lights and the least comfortable chairs you can imagine.

The greenroom at Largo is a small shrine to great talent. Images of David Bowie and Gilda Radner are tacked up on one wall. On a recent visit I found Apatow there with Stephen Merchant, a co-creator of the original The Office. Merchant and Apatow were discussing the best place in the world to see Bruce Springsteen (Milan, they concluded), while the musician Pete Yorn stood in the hallway tuning his guitar. A few minutes later, Sarah Silverman wandered in. Ali Wong showed up after that.

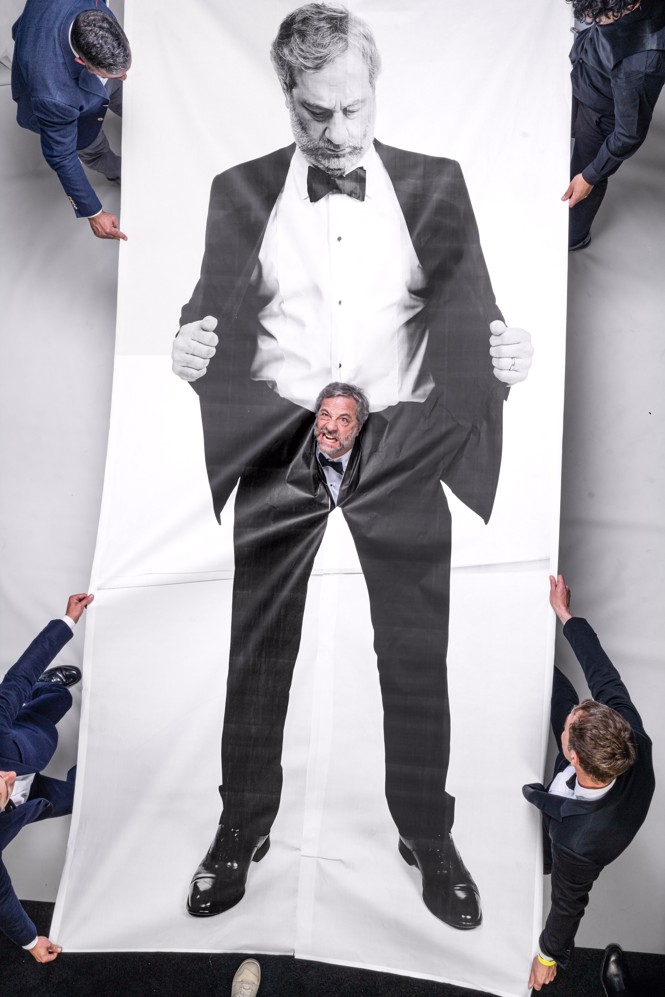

Apatow had assembled this group of comedic super-talent for Judd Apatow and Friends, a semi-regular benefit he hosts that combines stand-up and live music. For each show, he picks a different lineup, and a different cause—on this night, proceeds were going to the ACLU. Apatow had with him a chaotic pile of notes—scrawled by hand, photocopied, clearly out of order, some upside down. If he was nervous, it did not show.

Apatow’s set had a relaxed, funniest-dad-at-the-barbecue feel. He got huge laughs, from both old material (the hairy-back-shadow joke) and new, much of which involved confronting the indignities of aging. (“Don’t you hate diverticulitis? Isn’t it the worst when your high-school girlfriends start dying of natural causes?”) He also recounted a story about a quasi-religious experience he’d had while tripping on ayahuasca. (He’d told me the story before. “That really did happen,” he said.)

Apatow’s style is predicated on a confessional sort of self-deprecation, while Wong’s, for example, is more brash and confrontational—she told a story about a one-night stand that was so vulgar, a man sitting near me was actually honking with laughter, which prompted the people around him to start laughing even harder.

Apatow’s approach was clearly influenced by Shandling. Like his mentor, Apatow pushes a joke to get funnier until there is nowhere left to go. When he’s directing, he’s known to shout out one punch line after the next for actors to try, and then chooses which one to use in editing. (He still stews about bits of his films he wishes he could change.)

If Shandling taught Apatow to be exacting in his writing, he also helped him find ways to calm his galloping mind. It was Shandling who introduced Apatow to Ram Dass, the author of the best-selling 1971 book Be Here Now, which popularized Eastern spirituality in the West. When I first started reading Ram Dass, at Apatow’s urging, my immediate reaction was that it seemed very Los Angeles—we’re all just cosmic vibrations made to love one another, that kind of thing. It wasn’t until I listened to one of Ram Dass’s lectures that I had a revelation: Ram Dass’s belief system may have been Buddhism-flavored, but his delivery is basically a form of stand-up. He talks about going to India and meditating until he achieved transcendence. “I mean, light was pouring out of my head and I was some combination of the pure mind of the Buddha and the heart of the Christ”—here he pauses for just a beat before delivering the punch line—“which, for a Jewish boy, is not bad, you know?” The audience roars.

One of the best pieces of advice Apatow gives to other writers—which Schumer, Rogen, Birbiglia, and others all repeated back to me—is to write comedy like you’re writing a drama. The story has to work on a human level before it can be funny. “I think what he’s trying to get at almost always in all of his films and television is the vulnerability of the characters, and the comedy is secondary,” Birbiglia told me. “And because he’s so funny and he’s so comedy-obsessed, the comedy ends up being the thing he’s known for. But actually it’s the other thing that he’s extraordinary at.”

Apatow put it to me this way: “The jokes can’t work if the story doesn’t work. The whole thing will crumble. So the most important part is that you have a great dramatic story that you care about that tracks, and then you can figure out how to ornament humor where it’s needed. I think movies are usually bad when they haven’t figured that out.”

The director and Simpsons co-creator James L. Brooks told me about taking his 15-year-old son to see Superbad, a raunchy but sweet caper about a couple of teenagers trying to hook up with their crushes before they go off to college. Brooks’s son left the theater feeling like someone had “looked into his heart,” Brooks told me. Rogen, who co-wrote Superbad with his childhood best friend, told me he’d learned how to tell that story by watching Apatow (who produced the film). When you think about all of the talented actors, writers, and directors who do what they do because of Apatow, “I mean, the group of actors is big,” Brooks said. “He raised puppies.”

In the 1970s, when Steve Martin hit it big, Apatow went crazy for him. “I bought every album he put out—and couldn’t stop doing an impression of him for the next five years,” he recalled in one of his books. To a kid who worshipped the gods of comedy, Martin was the biggest of them all. So when Apatow was 13 years old, on a visit to California to see his grandmother, he persuaded her to drive him out past Martin’s Beverly Hills home. When they arrived, Apatow couldn’t believe his eyes: There was Martin, taking out the trash. He seized the moment, hopped out of the car, and asked for an autograph. Martin politely declined, saying he had to draw the line at signing autographs at his home. Apatow, ever quick-witted, suggested that they simply step into the street. But Martin insisted he could not.

When Apatow got back home, he wrote Martin an obscenity-laden, joking-but-not-joking letter, asking Martin why he treated his fans like garbage and threatening to share his home address with a Hollywood celebrity bus tour unless Martin responded with an autograph. When the reply came, it included a copy of Martin’s book Cruel Shoes. “Dear Judd,” the inscription reads, “I’m sorry. I didn’t realize I was speaking to the Judd Apatow.”

Years later, after Apatow had broken out, he and Martin were in a meeting together and someone asked Apatow to tell the story. “I told it,” Apatow recalled in Sicker in the Head. “And at the end, they asked Steve if that was how he remembered it. And he said, ‘In my memory, I knocked on Judd’s door.’ ”

Apatow is no longer the young apprentice—he has long since become a master himself. Now comedians constantly come to him for advice. Rogen runs every big creative project by Apatow, he told me. “I, to a fault, to an inappropriate degree, run everything by him,” Schumer said. “He honestly only gives good advice,” Dunham told me. The best advice he ever gave her is that a good note of feedback can come from anywhere. She took that to mean that real artists are confident enough to release a bit of control. (“Though he did once take me to a Who concert after a long workday, and I fell asleep and he took photos.”)

And yet Apatow has lost none of his enthusiasm for studying comedy. He has a scrapbook of a memoir coming out in October, Comedy Nerd, which tells the story of his life and is filled with the many photos, studio notes, and other documents he has hoarded over the years. He has continued to interview comedians, and published two books filled with those conversations. This is how I first got to know him. I had long wanted to find a way to get Mel Brooks into the pages of The Atlantic. I knew that Apatow shared my adoration of Brooks, and figured he was more likely to pick up a call from Apatow than from me. So I got in touch with Apatow to ask if he would do the interview. He said yes right away—and Brooks said yes to Apatow.

Apatow is now making a documentary about Brooks, while also developing films about Norm Macdonald and Maria Bamford. These projects follow his documentaries The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling ; George Carlin’s American Dream; and Bob and Don: A Love Story, about the friendship between Bob Newhart and Don Rickles. The same thread runs through all of these films: a deep curiosity about how people, despite their flaws and fears, find a way to keep going.

Apatow is drawn to comedians who deal directly with suffering. He executive-produced Gary Gulman’s stand-up special The Great Depresh, as well as Ricky Velez’s special, Here’s Everything, both of which are steeped in pain. When I caught up with Gulman recently, he described Apatow to me as a hybrid of Springsteen and Hal Ashby. Springsteen because of his relentlessness; Ashby because “there’s always that gut punch in Judd’s movies,” Gulman told me. “Even the ones that are almost absurd in the amount or the concentration of comedy.” Maybe especially those ones.

Not long ago, I had a conversation with Kelly Carlin, daughter of George, about what makes someone become a comedian in the first place. She had gotten to know Apatow when he made the documentary about her father, and had known Shandling as well. It is clear to her why Shandling had taken Apatow under his wing. “I really do think he saw that Judd was a very soulful, human guy,” she said, and that his reverence for comedy was real. For people like her father and Shandling, when you make something that you hope will make people laugh, and it works, “it’s like all’s right in the universe.”

“It’s a form of church,” Carlin went on. “There’s something about that shared space. My dad used to say that when you’re laughing, your heart and your mind are open.”

Shandling, who died from a blood clot in 2016, did not come easily to the wisdom that Apatow so admired him for. He spent his life working through the childhood death of his older brother from cystic fibrosis, and struggled to maintain relationships.

Apatow has experienced his own losses. During one of our conversations, he told me what it was like to be with his mother in the hospital as she was dying. She had ovarian cancer, and had developed sepsis. It was a terrible night and everything seemed to be falling apart. Right before she died, she looked up at her son and said: “Can you believe this shit?”

“That’s what comedy is,” Apatow told me. “We just have to laugh at how hard it is, and also really enjoy when we get a good moment.” The story made me think of a page in one of Shandling’s old diaries that Apatow is obsessed with. On it, Shandling had scrawled, in all caps: “GIVE MORE, GIVE WHAT YOU DIDN’T GET, LOVE MORE.”

I once asked Apatow if he tends to juggle multiple projects at once because, on some level, he thinks about Shandling, who died at age 66, and hears a clock ticking. Apatow said that wasn’t it. (“My dad is a young 83 so I feel I am going to live long, like the Russians in the old yogurt commercials,” he said.) He works so hard because he understands that most things never get made in the first place, and that plenty more get canceled when they shouldn’t.

For all of his success, Apatow still dreads failure. It’s much harder for anyone to make big comedic films than it used to be, even for Apatow, though Universal is fast-tracking his latest—a still-untitled film he is directing about a country-music star who has hit rock bottom. He told me that, long ago, he decided he would be content as the Elvis Costello of comedy: not the person who sells out Madison Square Garden but the person who makes great art for its own sake, for an audience who appreciates it, even if that audience is smaller. But several of his friends told me that he quietly worries about staying relevant.

Recently, I told Apatow that I’d come to believe he is the most well-adjusted anxious person I’ve ever known—few people can worry as much as he does and still come off as easygoing. “That’s just a solid facade,” he told me. “That’s why I probably just am drowning in pop-psychology books and religious books—because I don’t get me at all. I just don’t.”

What Apatow has learned, what he knows for sure, is that the good and the bad will come. No matter what you do, no matter how hard you work or how talented you are, life entails suffering. But you get to choose what you do with pain. If you surround yourself with people you love and respect and believe in, if you refuse to take yourself too seriously, then you begin to see that the darkness contains more light than might seem possible.

This article appears in the October 2025 print edition with the headline “The Invention of Judd Apatow.”

The post The Invention of Judd Apatow appeared first on The Atlantic.