Just as the characters dream—and have nightmares—in Tarell Alvin McCraney’s The Brothers Size, so too does this rightly famed play feel like a conjuring in front of an audience’s eyes: a slice of raw reality with many hallmarks of myth. It was first performed in 2005, and a pristinely mounted revival at the Shed (to Sept. 28)—co-directed by McCraney and Bijan Sheibani—is a beautiful way to celebrate its 20th birthday.

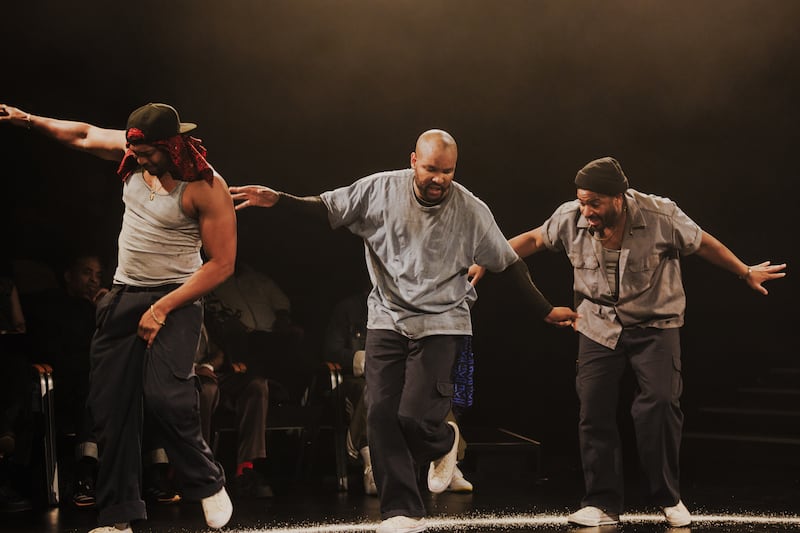

The action—more a piece of precise and beguiling physical theatre choreographed by Juel D. Lane—takes place within a circle of scattered salt, the audience seated all around. There are three characters: the brothers Ogun (André Holland, a star of the Oscar-winning 2016 movie Moonlight) and Oshooshi (Alani iLongwe), and Elegba (Malcolm Mays), an inmate at the jail Oshooshi has recently been released from.

With no stage decoration, we imagine the locations of cells, a repair shop, and the home the men occupy in the scrambled landscapes of reality and the imagination. (Twenty years ago, Holland played Elegba.)

The scoring on the floor—marks of very physical performances past, a snaking set of lines winding this way and that—speaks to tangled feelings and loyalties, and routes to past and future. The Brothers Size is influenced by the Yoruba storytelling traditions of West Africa; in Yoruban mythology, Ogun and Oshoosi are the gods of iron/labor and hunting/survival respectively.

The play, part of McCraney’s Brother/Sister trilogy of plays, has the same feel of heightened and burnished realism of Moonlight, adapted from McCraney’s Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue. A co-production with the Geffen Playhouse where McCraney is artistic director, it evokes the mixed feelings of an older sibling like Ogun, split between wanting to do all he can to make sure Oshooshi is alright, while also being at the end of his tether with being the sensible and responsible de facto parent. Oshooshi meanwhile strains against his brother’s intent for him to live a conventional life. Why can’t he do as he wishes, and live the kind of freewheeling life that the presence of Elegba represents?

The deeply felt forces of race, racism, and incarceration form the big-themed bedrock of the play; and in the confined space of the circle how little space Black men have to operate in a system all too keen to lock them up, and then find different ways to throw away the key even after their release into society. And so, The Brothers Size asks, what movement, progression, and potential is possible with such antagonistically stacked decks?

The chalk circle becomes symbolically significant: it is a universe of possibility, a circle of life that is both terminal but also holds potential, a world that is restrictive and expansive, playground and prison.

Accompanied by the propulsive music of Munir Zakee, Holland and iLongwe’s luminous performances encompass the shorthand of brothers, the spoken and unspoken intimacy of siblings who know which buttons to push for good and ill. Mays brings a teasing ambiguity to Elegba; we sense he might not be a force for good, the wrong kind of post-jail buddy—but we also become aware of what he too holds within. The trio share their frustrations, love, fears, hopes, and revelations in words and movement.

The Brothers Size is certainly intense. We know the brothers must be approaching a crossroads in their relationship. But there is also humor, song, and the promise of a future that may lead everyone out of that multi-defined circle. There is a price to any bid for freedom, but—thinking of all those tangled lines—also the chance that those forces that so frequently tear asunder may one day become routes to reunite.

The post ‘The Brothers Size’: ‘Moonlight’ Writer’s Masterpiece Returns 20 Years Later appeared first on The Daily Beast.