On July 18, I celebrated thirty years as a licensed New York City tour guide. This long-standing—and long-fulfilling—career began entirely as a side hustle; Broadway was my dream when I moved to New York from Florida in 1993, spectacularly unprepared for life in one of the world’s most expensive cities.

“Have you thought about being a tour guide?” another actor asked as we waited for an audition. “Tour guiding is basically performing…. Sometimes improv.” All I needed to do was memorize 400 years of New York history, art and architecture to get my license. How hard could it be? Turns out it was hard, with questions on the NYC tour guide license exam that included “Who painted the Rose Window at St. John the Divine?” (Spoiler: not me.)

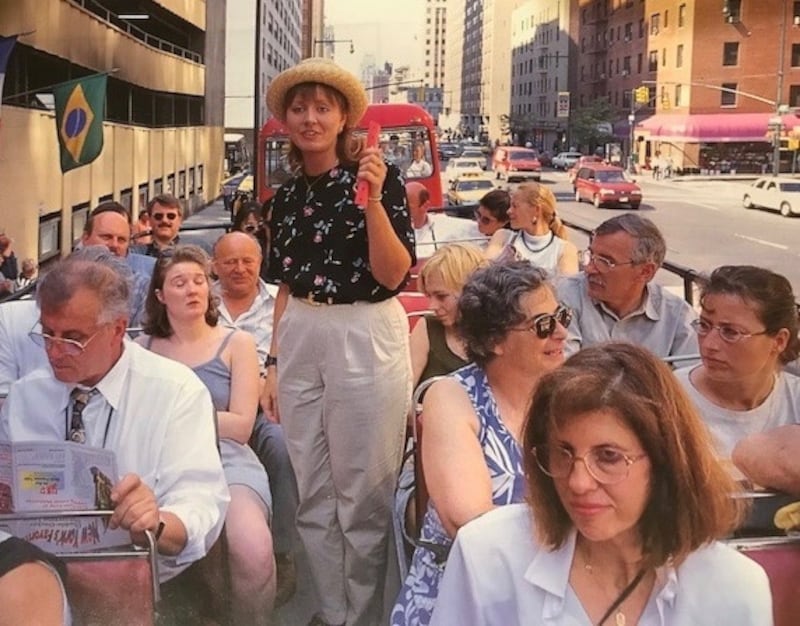

Somehow, I passed—with three points to spare. License in hand, I marched over to Gray Line and convinced them to hire me.

I’ve since led around at least 50,000 visitors from every corner of the globe up Broadway and down back alleys to see New York’s iconic landmarks and its hidden gems. We’ve traipsed around the city during blackouts, security alerts, financial crises, foreign wars and catastrophic storms. When a global pandemic emptied the city’s streets and closed its doors to the world, I thought my career might be over. Five years later, however, it’s clear I underestimated the resilience of this city and its continued allure.

Throughout the changing landscapes of the past 30 years, my primary goal has remained consistent: to help visitors fall in love with New York City, like I did when I first visited. I want them to see it as I do—alive and rich with stories.

But 2025 feels different.

In recent months, I’ve unintentionally led middle schoolers straight into an ICE protest and dealt with cancellations of foreign tour groups who were afraid of what they might encounter at U.S. airports. Whereas some groups are inspired by the Wall Street’s Fearless Girl or the AIDS Memorial, others scowl and mutter about DEI.

Tour commentary used to be a one-way street. Now, it’s more like call and response. Political polarization and the current administration’s policies have reshaped who visits New York, why they come, what they want to see and hear—and what they will believe.

Passing through construction currently underway in Battery Park, I explain how the park is being raised to reduce the risk of future flooding as sea levels rise. “There’s no such thing as climate change,” one man in the group yelled.

For 30 years, I’ve told visitors that Rockefeller Center and Trump Tower offer reliable public restrooms. But someone recently complained that I was telling people to “take a dump in Trump Tower.” My boss didn’t believe it, but he advised me to leave the building off my bathroom list, just to be safe.

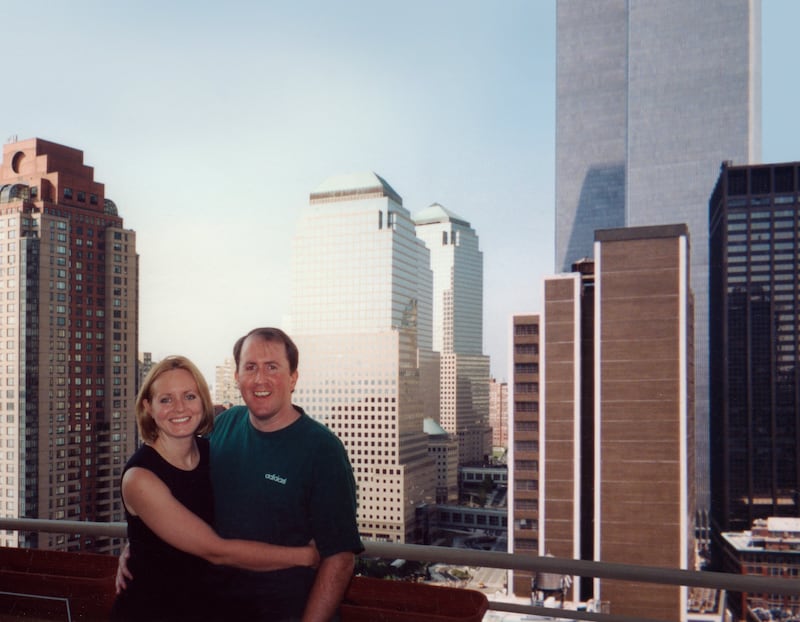

A trip to the observation deck in the South Tower, meanwhile, was a highlight of many of my early tours; today, I gather groups around the reflecting pool of the 9/11 Memorial and tell them about the day I saw the Towers fall. But these days, skeptics feel increasingly emboldened to question even my firsthand account of that day. And this year, I’ve lost track of the number of tourists who mention conspiracy theories—the demolition of WTC 7 in particular—to me.

“Although I tell groups I saw with my own eyes Flight 175 hit the South Tower, l was shocked when one individual second-guessed me after a tour: ‘Did you really see that plane hit?’”

In July 2001, I moved with my new husband into an amazing apartment just six blocks from the World Trade Center complex. We were standing on our 24th-floor balcony of that apartment on the morning of September 11 when a passenger jet roared just above our heads and crashed into the South Tower. Barefoot and in my pajamas, I ran down flights of stairs while my husband followed with our 40-pound dog. Then the towers crumbled, trapping us in a toxic snow dome of dust and debris. We wandered for hours, covered in ash and gunk, before being evacuated from Manhattan by boat.

It was weeks before we could return to our apartment. It was much longer before I could return to guiding tours. The Financial District had become a restricted zone; tour buses were banned from Wall and Broad Streets.

My first post-9/11 tour was in March 2002, with a group who showed up only because they had booked before the attacks and couldn’t get their deposit back. For three days, my job wasn’t just pointing out landmarks, it was convincing them that New York would rise again. And it did.

For the next decade, until the memorial opened in 2011, I guided visitors through a series of makeshift viewing platforms overlooking Ground Zero. From the overlooks, we could see the cleanup and then the rebuilding. We could process together the sheer destruction of 9/11 before turning back toward the city’s vibrant streets—a reminder that New York had literally risen from the ashes.

And in reminding tour groups that New York would not capitulate, I was also reminding myself. The city’s resilience became mine too.

On a recent 9/11 Memorial tour, I asked a group of high schoolers (from my home state, no less) to remove their red MAGA hats. Whatever your politics, I explained, the memorial is essentially a cemetery—all hats should be removed as a sign of respect. They did, but I knew the move was risky; complaints about perceived slights could get me blacklisted from certain tour companies. But it felt too personal to focus only on my tips and reviews.

Today, I’m battling uterine cancer, now officially linked to World Trade Center toxins that, as of 2023, may qualify me for federal healthcare compensation. But recent cuts to the 9/11 fund could threaten my treatment. I share this with tourists not to make a political point, but because it’s my story, my history, and my truth.

My work and my life are fundamentally intertwined, and nowhere has that felt more profound than at the World Trade Center. I’m one of the only guides still working in New York who led tours through the original World Trade Center site, witnessed its destruction, and now guides people through its rebirth.

As the 24th anniversary of 9/11 approaches, I wonder how visitors might perceive my beloved city if armed federal troops are patrolling our streets and landmarks. If this comes to pass, my job, as always, will be to steady nerves and remind people of an undeniable, universal truth—whatever your politics, your biases, your fears—that New York always endures. And I will keep telling that story, in all its beauty and complexity, to anyone willing to listen.

The post Opinion: What It’s Like to Tour Ground Zero With 9/11 Truthers appeared first on The Daily Beast.