When Christopher Columbus first set eyes on Bocas del Toro on Oct. 6, 1502, he was struck by the area’s natural beauty. The archipelago, located on present-day Panama’s northwestern Caribbean coast, was a remote and untamed frontier whose swampy terrain, relentless tropical diseases, and absence of major gold deposits had—until then—kept colonial powers at bay.

In the centuries that followed, the region became a haven for pirates, foreign settlers, wealthy landowners, and their enslaved laborers.

Then came the bananas.

First domesticated in New Guinea some 7,000 years ago, by the late 1800s, the Gros Michel variety had become a hit in the United States—cheap, available year-round, and even recommended by doctors. As demand skyrocketed, U.S. fruit companies began securing vast tracts of land in Central America. And Bocas, with its fertile soils and access to global shipping routes, was an ideal location.

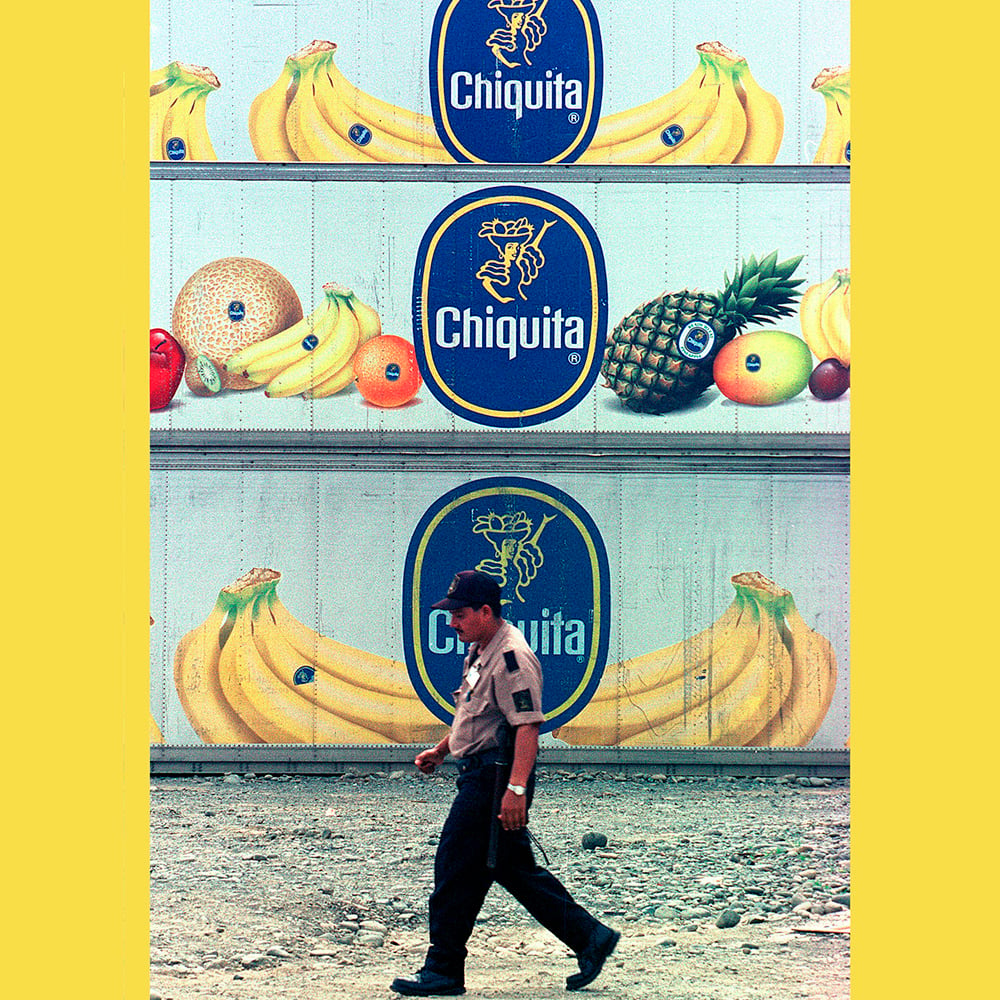

In the 1890s, American entrepreneurs began planting bananas in Bocas del Toro, and in 1899, their farms were acquired by the newly formed United Fruit Company (UFC), forming the world’s largest banana enterprise. Though UFC—later known as the United Brands Company and Chiquita Brands—was not the first to introduce bananas to the Americas, it was among the first to organize large-scale, commercially driven cultivation to meet the growing U.S. demand.

And as the banana industry grew, so too did Panama. UFC’s early days coincided with Panama’s nascency as an independent country, and the development of the company was responsible for a great deal of the development of the region. Granted significant land concessions, UFC and its subsidiaries acted as something of a parallel government in Panama’s northwestern coastal lowlands, building and administering sprawling plantations to grow bananas; roads, railways, ports, and canals to transport them; and entire towns—complete with schools, hospitals, housing, and infrastructure—to accommodate its workforce.

This immense influence, however, came at great cost. Because the company, rather than the state, controlled so much of Bocas del Toro’s early infrastructure, many workers were entirely dependent on the company for their livelihoods—for instance, they were often paid in tokens that could only be used at company-owned stores, instead of cash. Even into the 1970s, Bocas del Toro’s schools were staffed and paid for by the company, and the region remained accessible only by sea and air, without public systems linking the region to the rest of Panama.

Of course, with the banana industry also came labor struggles, racial and ethnic segregation, political corruption, and environmental hazards—not to mention the infamous incidents of violence and political interference elsewhere in Latin America. But bananas nevertheless became the backbone of Panama’s economy, both a vital export and source of employment.

Today, Panama is no longer a top banana exporter. (According to the United Nations, the top exporting countries in 2024 were Ecuador, Costa Rica, the Philippines, and Guatemala.) But there is perhaps no country that has been more profoundly shaped—politically, economically, and geographically—by the banana industry. Which is why recent events have come as such a shock.

-

Women in colorful dresses hold umbrellas.

-

Workers stand with their arms crossed in front of a mural showing people in hats with their fists raised.

In recent months, a long-simmering crisis came suddenly to a boil in Bocas del Toro.

After Panama’s National Assembly passed a controversial social security reform in March, workers nationwide began to strike, including teachers, construction workers, and doctors.

On April 28, they were joined by members of Sitraibana, a powerful banana worker’s union, who walked off the job at a Chiquita Brands plantation in Bocas. Union leaders asserted that the legislation would undermine existing benefits specifically negotiated for banana workers in 2017. Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino condemned the banana workers’ strike, and a labor court declared it illegal, but workers held the line.

Within days, the protests spread, and Panama was engulfed in one of its most volatile social uprisings in recent memory. In Bocas del Toro, protesters blocked off roads, preventing fuel, food, and other shipments from coming in or out. The banana industry ground to a halt.

By late May, after reporting $75 million in losses due to stalled operations and the destruction of crops, Chiquita shut down its operations in Panama and initially laid off 5,000 workers, citing “unjustified abandonment of work.” Chiquita said it had repeatedly called for workers to return, but “irreversible” damage had already been done. Mulino defended the mass layoffs, saying the company was acting within its rights under the labor court’s ruling.

The impact in Bocas was immediate. “Almost the entire economy of the province depends on banana cultivation, and Chiquita has been the only major employer for years,” Aris Pimentel, president of the Bocas del Toro Chamber of Commerce, said at the time. Unemployment surged in a province where just 36 percent of residents have finished secondary school and nearly 75 percent are Indigenous, two deep-rooted barriers to employment in other sectors.

On June 11, under mounting pressure, the government struck a deal with Sitraibana: The blockades would be lifted in exchange for drafting a special pension regime. Lawmakers soon fast-tracked and passed Law 471, granting banana workers better benefits and protections. The banana workers’ union strike ended, but protests persisted, and confrontations surged across the province—signaling that public anger had outgrown the original labor dispute.

On June 14, the government shifted its approach from dialogue to force, launching Operation Omega—a police and riot squad effort aimed at clearing road blockades and suppressing protests in Bocas del Toro. Authorities deployed troops, suspended certain constitutional rights, and imposed a partial communications blackout. More than 200 people were arrested, according to one estimate from La Prensa, a major Panamanian newspaper; among those detained was the head of Sitraibana, Francisco Smith.

Four months after the strike began, sporadic unrest continues in Bocas and Panama at large.

But on Aug. 29, Panama signed a memorandum of understanding with Chiquita to restart banana operations in Bocas del Toro, ending the prolonged state of uncertainty. Under the deal, Chiquita will invest an estimated $30 million to revive production on 5,000 hectares of plantations, creating 3,000 jobs in the initial phase and another 2,000 in the second stage. Operations are scheduled be fully underway by February 2026.

It is likely a relief to the Mulino administration, which faces pressure from the public amid rising unemployment and local unrest, and from the private sector, which wants to restore investor confidence and protect Panama’s economic image. It is also likely a relief for those whose incomes are dependent on the banana industry, particularly in Bocas, where extreme poverty is pervasive and employment opportunities are concentrated in a single sector.

But for some, the recent unrest is the visible expression of the fragile labor and environmental ecosystem that has underwritten the banana industry for more than a century. When the banana industry resumes in full, it will have to reckon with looming problems that, without reform, could threaten its future viability.

From its earliest days, the banana industry has had a fraught relationship with labor. Conditions have improved over time, but today, the global banana industry still heavily depends on an often-exploited workforce. Many seasonal and migrant workers—particularly from Indigenous communities—face predatory recruitment practices, wage theft, and substandard living conditions. Workers also endure increasingly hazardous conditions—scorching heat, flash floods, and aggressive pest outbreaks—on plantations where wages lag behind increasing productivity.

Labor risks are exacerbated by exposure to pesticides, both historical and current. Decades after the widespread use of the nematicide DBCP—which allegedly caused sterility and reproductive harm for more than 1,000 Panamanian banana workers—residents and workers in plantation areas in neighboring countries continue to face elevated risks of cancers, chronic kidney disease, infertility, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Contemporary pesticide use, including fungicides and insecticides applied throughout the year, further compounds these risks across Central American banana-producing countries.

Meanwhile, environmental and climate issues are taking a significant toll in many producing regions worldwide. Beyond chemical runoff and deforestation, the banana industry’s extensive use of inorganic fertilizers and poor management of plant waste contributes significantly to regional greenhouse gas emissions. Expansion into previously uncultivated lands—often in response to declining yields—exacerbates biodiversity loss and carbon emissions, threatening fragile ecosystems in mountain foothills and coastal zones.

Climate change is already negatively affecting banana production across Latin America, creating lower yields, tighter supplies, and shrinking market volumes. A 2025 study warns that up to 60 percent of Latin America’s prime banana-growing areas—home to 80 percent of global exports—could be unsuitable as soon as 2061, with few options for relocation given the particular growing conditions needed for the preeminent Cavendish variety.

Plus, the region’s warming, wetter conditions are fueling the spread of devastating plant diseases, including the fungal pathogen Tropical Race 4 and Black Sigatoka disease, which has been found on plantations in Bocas.

Addressing these problems will require more than isolated fixes. Many Panamanians, like José Pérez Barboni, a member of the National Assembly, see the latest turmoil as an opportunity for a broader change in how workers are treated and how the land is stewarded. “I see this as a chance to renegotiate the terms—placing workers at the center of the conversation—while also creating more jobs, generating income, and perhaps even diversifying production,” he told Foreign Policy.

As part of the new agreement, the president of Chiquita, Carlos López Flores, said that the company will restart in Panama “under a new operating model that is more sustainable, modern, and efficient, generating decent jobs and contributing to the country’s economic and social development.” It is not yet clear what that will entail, but it seems to indicate a recognition that the industry’s current model is not sustainable indefinitely.

Investments in climate adaptation measures, such as increased irrigation, enhanced pest and disease management, and more resilient planting materials, are expensive. Historically, companies have dealt with crises by pushing costs downward onto plantation workers. But smaller operations in Panama have found other ways of doing business.

The Chiriquí province, which borders Bocas del Toro, is home to local cooperatives experimenting with sustainable and equitable banana production. Demetrio Javier Díaz, the president of the chamber of commerce, industry, agriculture, and tourism in the Chiriquí town of Boquete, suggested that these cooperatives could offer a model for a way forward, either as a parallel or long-term alternative to the current system.

Unlike the multinational system, where profits and decision-making are concentrated abroad, cooperatives keep wealth and agency within the communities that actually cultivate the fruit. This allows workers to share ownership, have a direct voice in how farms are managed, and benefit more fairly from the value of their labor.

A cooperative model could also encourage diversification, combining banana cultivation with alternate crops or with small-scale tourism projects, reducing the dependency of regions such as Bocas del Toro and Chiriquí on a single, volatile export. Joseph Archbold, a Bocas-raised chef and founder of Bocas Hospitality Group, told Foreign Policy that he sees great potential in cocoa, adding, “We don’t have to repeat the history of exporting raw materials without added value. Right here, we can transform that cocoa into … products that tell our story and generate local employment.”

Moreover, by emphasizing training and education, cooperatives can help workers build the skills needed to adapt to new agricultural practices or even shift into other sectors when climate or market pressures make banana farming uncertain. In this sense, a cooperative is not just a business alternative—it is a pathway toward community resilience, environmental stewardship, and long-term prosperity in areas historically vulnerable to the exit of large corporations.

Archbold grew up around the banana industry, where his father spent his entire career. He remembers “watching ships loaded with bananas leave the port, listening to stories about how that enormous machinery worked.” But he, like others, thinks the current monocultural model is no longer sustainable, for a range of environmental, economic, and social reasons.

Whether due to the construction of the Panama Canal, the presence of U.S. military forces, the dominance of multinational banana companies, or the expansion of foreign mining interests, Panama’s history has often been defined by struggles for sovereignty against external powers. What comes next is perhaps another chapter in that history.

As Archbold puts it, “Bananas are part of our memory, but I believe the future lies in daring to imagine something different—more diverse, more sustainable, and above all, more ours.”

The post Bananas, After the Strike appeared first on Foreign Policy.