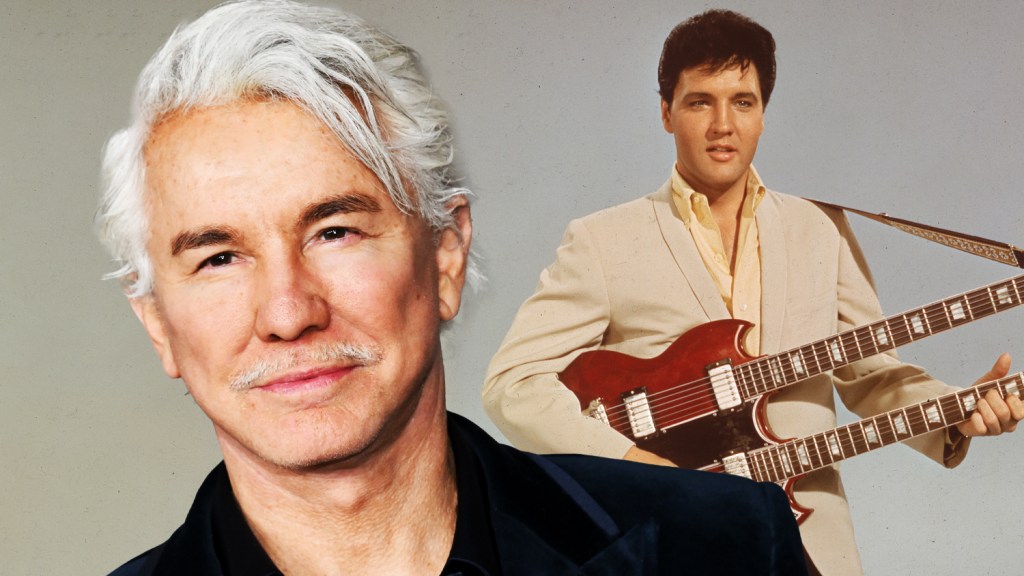

EXCLUSIVE: It’s difficult to shake rattle and roll Elvis Presley out of your system once you’ve immersed yourself in the life and music of The King. Elvis star Austin Butler took forever to lose Presley’s vocal patter and mannerisms. The film’s director Baz Luhrmann was also not immune. He extended his Elvis experience to make EPiC: Elvis Presley In Concert, a film that is one part concert and one part documentary, with pristinely restored lost footage from his 1970s residency in Las Vegas that will be a feast for Elvis fans and dispels the notion that the singer became simply a bloated caricature and a shadow of the young man who forever changed music. There is a playful running dialogue through this film, over whether Presley was to be hated or beloved, and whether he could really even sing. Luhrmann’s dogged sleuthing of lost footage and restored vocals settles the latter question in the most convincing way.

DEADLINE: Before I draw you out on your inability to let go of Elvis Presley, I wanted to draw you out on the next epic, the Joan of Arc drama Jehanne d’Arc. Deadline revealed you’d found your heroine in Isla Johnston (The Queens Gambit) but I’ve since heard you might push your start and released some stages you’d secured in Australia. Is there a delay?

LUHRMANN: It’s the usual give and take. There’s a reason it often takes me ten years go make a movie. Part of that is I do the visual language part, the music and everything else, and they had room to fit in another movie before I needed them, and I was like yeah, fit it in because I won’t be shooting until next year. I respect the way other people make movies, but people shoot. And for better or for worse, I’m not going to be hurried. I have the idea, write on it, do the visual language and music, all the politics with studios, I cast. I once got into that race thing, when I had Leonardo DiCaprio for Alexander, and I tried to push and found it isn’t me. Oliver Stone was really obsessed with the same subject and he pushed his into production, and I had some personal, family stuff. I respect the way other people are, but I’m just going to do things in my way.

DEADLINE: You’re bringing back memories. Aside from your race, there was those rival infectious disease movies, with the Dustin Hoffman-starrer Outbreak winning by starting production and then promptly stopping to finish the script when the rival Crisis in the Hot Zone they Ridley Scott was directing with Robert Redford and Jodie Foster based on the terrific Richard Preston non-fiction viral scary book. We see a lot more caution now, and while those horseraces were fun to cover, the resulting movies were disappointing and probably hurt by rushing.

LUHRMANN: I say one thing in filmmaking: once the train has left the station, you can’t put the train in reverse. The more time you spend getting ready, the better chance you have of capturing what you’re after. I reckon we’ve known each other 20 years maybe, but in 35 years, I think I’ve made, I don’t remember how many, but there’re about five or six movies.

DEADLINE: Five or six memorable visual spectacles...

LUHRMANN: Well, thank you.

DEADLINE: This is a departure for you, coming to TIFF with a title up for acquisition. You sneaked me a peek at EPiC: Elvis Presley in Concert. I’d thought that when he emerged from the atom splitting moments of him you depicted as he became this edgy risk taker who inspired so many kids to become musicians, he went to Vegas and became a caricature in a jumpsuit. I stand corrected; he was a badass who could really sing, from what you captured.

LUHRMANN: I’m glad that’s your most visceral or immediate takeaway, Mike. As a kid, I had some Elvis fandom for sure, I did love him. But then I went on to Bowie and Elton and people like that. I lived in a small country town. Bowie was scary. The Stones and Beatles of course, and that expanded to even Bachman-Turner Overdrive, the Tijuana Brass and opera. Dad had a reel to reel tape recorder he brought back from the Vietnam War, and I was exposed to a variety of music. But in doing the movie, I was reminded how much Elvis was in my mind as an influence. The reason I really chose Elvis as a subject was that as a canvas, he really reflected America’s journey like fifties and beyond. I still have trouble explaining to young people now, or even audiences just how scary Elvis was to the previous generation who had come home from the war, didn’t want any more noise, or anymore battles. They wanted to move to the suburbs and live The Dick Van Dyke Show.

DEADLINE: Elvis had other ideas…

LUHRMANN: Elvis was like the devil. It’s so not an exaggeration considering his growing up in and around black music, his physicality, his overt sexuality and his attitude. He and James Dean were essentially twins. One being an actor, one being a musical star and an actor too. Elvis admired Dean, beyond the beyond. As he said, James Dean was a genius. I’ll never be as good as him, but they both scared the adults. And then what happens is that after the war, he was driven very much by [manager Col Tom Parker]’s idea to make him a family entertainer. And that’s all those films.

DEADLINE: I wasn’t a fan of those.

LUHRMANN: Now, to be fair, Mike, we had a tiny little cinema in our country town, and we loved our Elvis matinees. I thought he was the coolest. But it turned him numb as it made him the highest paid actor in Hollywood. He was the first actor to get a million bucks a picture, but it made him numb, in a river of money. And then suddenly boom, something happens which I try and hint at. John Redmond, who I’ve been editing with for 22 years, we were really creative partners on this because it is found footage. I didn’t shoot the footage. And he brings a lot of the poetry to it. We tried not to be too didactic, but more, that’s why I say, and I can’t underline this enough, I say it’s epic. Elvis is fully present in concert, Elvis sings and tells his story like never before. I say it’s not a documentary and it’s not a concert film. It’s epic. What I really mean is if you would ask me, honestly, it’s a kind of tone poem on the person and the performer himself.

But you’re right. When he is in Hollywood movies, there’s the substance abuse problem that factors in, and he gets lost as The Beatles come along like a blinding flash of light. There’s suddenly politics. There’s the whole Vietnam of it. The world seems to be erupting and he feels irrelevant. And that’s when he decides, after eight years, to go back in front of an audience and no one sees what’s coming. When you see him rehearsing, and developing the big band sound and all that, no one had seen Elvis do that.

DEADLINE: But there’s a moment when a journalist asks him about entertainers speaking up about the war. His answer was a publicist’s dream, he thinks of himself as an entertainer and wouldn’t take the bait. I don’t think would’ve been the answer that John Lennon or Paul McCartney would’ve given, or David Bowie or Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

LUHRMANN: I don’t know if you noticed, because I’ve seen that moment many times. His publicist, the Colonel was right next to him and he goes, no, I’m just an entertainer. I want to keep my opinions to myself. But then the next question is, do you think other artists should keep their opinions to himself? And he goes, no, absolutely not. Meaning they shouldn’t. People I’ve spoken [still respected him]. Bob Dylan, the great protest singer, says one of the greatest moments in his life was when Elvis recorded one of his songs, which is in that movie of ours.

DEADLINE: If you listen to Elvis’s interviews very early on, he’s refreshingly edgy.

LUHRMANN: And you hear a bit in the beginning of the movie, he goes, well, he’s just an idiot. I’m not saying it’s only that the colonel isn’t a colonel, but Elvis becomes complicit in let’s say, leaving all of the business to the colonel. There’s a line in there too where the guy says, now, do you get a cut of all of the merch that’s being sold, including the ‘I Hate Elvis’ badges? And Elvis says, ‘really? Honestly, I just don’t know.’ Because all Elvis really wanted or cared about was being in front of an audience. It’s the only love he truly trusted, along with Lisa Maria as a child. But it’s the only love he really knew. I think that the colonel very early on stops him from doing interviews.

DEADLINE: From your treatment of The Colonel in the form of Tom Hanks in Elvis, I could feel the contempt you felt for that guy who kept Elvis from touring abroad and doing things that benefited Parker and his gambling debts more than fulfilling Elvis’ artistic potential. You treat him a big more playfully in this documentary. Why?

LUHRMANN: I can be really clear about my attitude towards the Colonel, but I only see it as storytelling. There is absolutely no question. The colonel was a marketing a salesman genius. Think of this kind of personality, someone who can sell the world anything. He’s a carnival barker, but a very brilliant genius salesman. There’s a news book by Last Train to Memphis author Peter Guralnick, who had access to the same research I did after I spent 18 months at Graceland reading the same stuff. You meet people who were around, and they say the Colonel was a scoundrel, with a twinkle in his eye. Meaning, you have no idea how many people love being worked over by the colonel. I haven’t yet read Guralnick’s book, but was told he did include in the end, the independent investigation into the Colonel where the determination when Priscilla and the estate sued the Colonel was absolutely that he absolutely overreached in his exploitation of Elvis. There was no question that he was ripping Elvis off, for a very long time. I don’t know if that included the gambling addiction and all of that. I tried to show this was both a somewhat loving but also toxic relationship. You could compare it to maybe a Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf-type marriage.

DEADLINE: Including the delay when Hanks became the first major star to go down with Covid, how many years did you live in full Elvis immersion to make that narrative film?

LUHRMANN: I’ve been going back through old photo files and found notes about Elvis even around Moulin Rouge time, so it’s over 20 years ago. But in terms of seriously, John Redmond and I made an Elvis reel, found footage, and when we started finding footage, we always thought, gee, if we do the Elvis film, we must make something like EPiC. And that reel was made seven years ago.

DEADLINE: We saw how long it took Austin Butler to stop talking and moving like Elvis after his long immersion. What was the most compelling thing that brought you back for more after you too had shed Elvis?

LUHRMANN: Responsibility? It’s hard to be clear about this because you have a lot of Elvis fans out there. There’s a lot of bootleg material out there. There is footage Elvis, that’s the way it is. Elvis on tour. There are versions of those films out there, and there’s a lot of bootleg material out there. But when I went to make the Elvis film, I had the money and the resources to go into the salt mines that are in Kansas and look for these rumored negatives [of these performances]. Now, people who don’t have a technical understanding, there might be bootleg, but that is scratchy stuff with not very good sound. But we found more than we imagined. I wanted to try and reconstitute it for some of the big Vegas stuff, but it turned out it was better for me just to build the sets. And I hadn’t been prepared for the level of craft and absorption and commitment that Austin brought to being Elvis, when I thought, I should use the real Elvis. There were a few snippets of the real concert in my movie, but now I’ve found all of these reels of negatives, with no sound. It’s very important to say no sound right?

DEADLINE: Doesn’t that defeat the purpose? No sound?

LUHRMANN: Yeah, no sound. But I go, well, I can have them all put back into the salt mines and you’d never know. Some of the footage has never been seen before because they shoot six nights of concerts at the MGM and some of it’s eight mm that had never been seen. The stuff you saw of him in the gold suit in Hawaii, that comes from the archives in Graceland. What do I do? I think, I can’t just reheat up and yet another version of Elvis. That’s the way it is. Elvis on tour. So [editor Jonathan Redmond] it took so long to digitize, to print, digitize lip read, to work out what he’s actually saying, and then find old VHSs or our work prints and scrape back the vocals. Most of it is Elvis’s original vocal from stage. And definitely Ronnie Tutt the drummer, his drumming was recorded well, as was the guitarists. Some of the voices, and strings or brass we had to rerecord. After all, this is not to be a documentary in the sense of we just used exactly what was on stage. That was not possible, so what we made is a sort of cinematic poem.

DEADLINE: What does that mean?

LUHRMANN: What if Elvis was here now, what would it sound like? And the most important thing, and you only saw it half finished, but I’m just about to go and sign off on the IMAX version. You’ll never have seen Elvis in Vegas or on tour at this scale, onscreen at this quality sound level. So the money has really been put into, like we say, epic. Elvis sings and tells his story like never before. We also found some previously unreleased recordings of him telling his story and we use a lot of preexisting stuff that people would know, but a lot of him saying things that an interview was about a 50 minute interview that had never come out of the vault before. That was shot when he was on tour audio, audio only.

DEADLINE: Who gives you’re the needed permissions to wade through the Graceland archives?

LUHRMANN: People assume that Graceland, the estate owns and controls Elvis, but actually it’s split up into several layers. Elvis’s image. And the Elvis name is owned by a group called Authentic Brands who we know very well and have been very good partners, and they’ve started a studio called Authentic Studios. But the other part of history is that Warner Brothers buys MGM, and MGM made those Elvis movies. This is Elvis and on tour, so actually it’s the MGM vault that is in the salt mines. Warner’s gave permission because I’m working with them, and I was making Elvis with Warners, and it costs a lot of money, man. There is stuff in those vaults you wouldn’t believe, but it costs so much money to go into the sealed vaults to bring it out to dry the negative, to run the negative. You have to get the old machines. I think we had someone on it for two years just going through negative and printing. And then authentic brands who they own Elvis’s image, likeness name, and they also control quite a bit of publishing. And then Sony Vision, the real producer of this, one of the big producing entities is Sony Vision, not Sony Pictures, and not Sony Records, but Sony Vision, which is a new division, an exciting division, which is devoted to music movies. I also have a label with RCA and RCA was also Elvis’s label. So I have a particularly privileged access to the music. And then in the end, when I was at Graceland, Lisa Marie controlled who goes in and out of Graceland, even though they don’t control the estate, they actually control the traditional notion of this state. They control Graceland. And Lisa Marie gave me the great privilege of access to areas other people are not allowed into, including the upstairs area, which is a gift. And that I’ll always cherish, I’ll always cherish. And now that responsibility has fallen to Riley Keough. Aside from being the granddaughter of Elvis, she’s a fantastic young actor, singer and filmmaker. Actually, Mike, keep an eye on her as a filmmaker.

DEADLINE: You intersperse performance with footage from those movies, usually Elvis in a race car. Or the scene of him singing Bossa Nova Baby in white dinner jacket, which had to be Quentin Tarantino’s inspiration for Leonardo DiCaprio’s Rick Dalton doing an identical looking song called The Green Door…

LUHRMANN: That’s exactly what Leah is doing, Bossa Nova Baby.

DEADLINE: You mention the movies numbed Elvis. What did he want out of Hollywood besides a paycheck? Why weren’t the movies better?

LUHRMANN: Oh, Mike, let me tell you something little known about Elvis. He was a movie usher as a kid. He saw Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove seven times. His greatest love was to book out the theater and watch movies, over and over and his movie tastes were really quite extraordinary. He was a huge Kubrick fan. And do you know why we have Thus Spake Zarathustra at the beginning of his show? It was from 2001: A Space Odyssey. He was a mad movie fan. And let me tell you something. If you look at his early films, you see that film in the beginning, like Loving You or The One I Love, which is King Creole. His acting is very good. And in fact, it was directed by the same director who directed Casablanca and people were saying, and it was well known that he had real acting chops. And as he says in our documentary, ‘when I went to Hollywood, I really thought they’d give me a chance at doing a serious role.’ And he tried to. But one thing that the Colonel was really aware of was that you have Elvis sing in a movie, you make a river of money. Nobody really wanted to see Elvis, they wanted to hear him. The Colonel took care of all the business, and they got so bad. And as he says in this movie, he said, you couldn’t have paid me more money to feel less satisfaction.

He became self-loathing about it. There were times when they stopped even making new music. They just find what they had around. He didn’t even read the scripts. He just turned up and did them. Some of the early ones are fun and good, like Blue Hawaii. I think Viva Las Vegas is fun, and Ann-Margret and he had real electricity. But they get so silly and he gets so self-loathing, he just doesn’t really care. And that is why he goes back to the audience after eight years. He says, I got to show people what I can do. He actually says that. I’m not a joke. I started out as a unique creature. I have to try to find my way back to that.

DEADLINE: Was there a role he really wanted only to have the Colonel get in his way?

LUHRMANN: One that really hurt Elvis was, I think it was a Peter O’Toole picture that won the Oscar. And I think the head of this studio said, yeah, we make those cheap Elvis movies so that we can afford to make real art. And that really hurt Elvis. I believe Elvis was being considered for West Side Story, which he was really into. But the big moment was A Star is Born. The possible partnership between Barbara Streisand and Elvis Presley fell apart. And that story, I won’t go into it, but of course Parker’s ex-wife Loanne was very protective of the Colonel. That’s understandable. But there’s no question that the Colonel didn’t really help that along. That’s something that Barbara was really driving for. It came down to shared billing. But the thing about Colonel…he wasn’t like this villain that’s traditional. He was funny, and he was charismatic and unbelievably manipulative, and he also could always suck the air out of any room. He was never in the room that he didn’t suck the air out of it.

Remembering that he grew up as a carnival trickster, really, and he thought it was funny to snow job people. He made up this club called the Snowman’s League. I mean, the president of the United States was in his Snowman’s League. It was free to get in, but $10,000 to get out. And the rules, if you give you the rule book and you open it, and it had no rules, nothing in it. Funny, right? But it’s also very manipulative. And I had a great conversation the guy who directed the Comeback special, and he says to me, he says, I still never understood why so many people with power were so nervous about the Colonel, why they feared the kernel. I didn’t have an answer. But I think the Colonel in his own way was always affable and likable. And I tell you, I can’t tell many how many people have been ripped off by the colonel and still tell the story with a smile on their face.

DEADLINE: During one of the panel discussions we did for Elvis, I told you I’d watched Dave Grohl interviewed Dolly Parton, and she was still very shaken by trying to have Elvis sing her song I Will Always Love You, which she wrote while she was broke. The Colonel tells her not unless she signs over half the songwriting rights to them. And she is just completely dumbstruck by that. You worked a subtle reference to the song into the movie. Good for her that she stood her ground, and was rewarded when Whitney Houston came along and sang it in The Bodyguard. How many songwriting credits does Elvis have that were gotten by the Colonel’s strongarming?

LUHRMANN: Well, he’s very articulate about that. He doesn’t ever claim to be a songwriter, and many of the concepts the Colonel came up with are still copied today. If he didn’t invent merchandise sales, he really invented the modern concept of merchandising. He focused more on the calendars and the posters and the balloons and the t-shirts than anything else. But with publishing, that was absolutely his idea. Elvis really didn’t do any of the business. He just needed the cash. But you’re right. I had a great conversation with Dolly Parton because I wanted to use Dolly Parton in Moulin Rouge, and she said, well, you might make that song a hit three times. I use it at the end of the Elephant Love medley. It’s the last song. I believe he sang I’ll Always Love You to Priscilla after they have their divorce. That’s what I hinted at in the movie.

Dolly said, but Colonel, that’s my family’s legacy. And so now I believe Elvis is on record as saying, I don’t believe in the monopolies of record labels owning the publishing. He was very not about that. And in this film, we don’t really go into it. See the Colonel as just this two dimensional villain; he was actually a clown with a chainsaw, but he was also a business genius. The Colonel said, I’m not a manager, which got him out of his legal situation. I’m a promoter, and a promoter is a seller. Doesn’t matter what it is, I’ll sell it. You can fill in the metaphor. A manager actually looks after the person and makes sure that the artist is flourishing, is going to have longevity and choices. The Colonel also had a gambling addiction. It’s well known, and he sold the catalog to RCA in desperation. So there is that. One thing I will tell you though, and I hope we get it from the movie, is that people wonder about the spirit of Elvis and the kind of person he really is. Nobody wanted him to record In The Ghetto. Even his closest allies said, don’t do that. It’s too political, right? But he did do it. He sings, Walk a Mile In My Shoes, that poem about about If you could be me for one hour. He sings, don’t judge others. Try and see it from their point of view.

I hope that the underlying feeling you get is we see Elvis because he’s really good looking and he’s really incredible on stage. He never rehearsed dance moves. I learned this from Mick Jagger. Jagger said to me, the thing about Elvis is I would say, okay, I’m going to practice this step. And Michael Jackson, brilliant dancer, would practice the step. Elvis, never stood in front of the mirror and practice steps. He said, well, I just feel it out there. He’s almost like in a spiritual state now on stage, so confident and so in control, and so at ease. But off stage, he was still that very insecure little boy from the poorest of the poor part of Tupelo, whose father went to jail, whose mother had to leave in the middle of the night and change locations. And who never, ever felt quite good enough and was looking for, I think the affirmation of unconditional love and the only unconditional love he probably felt came across the footlights.

The post Why Baz Luhrmann Could Not Shake Elvis And Made TIFF Premiere ‘EPiC: Elvis Presley In Concert’ appeared first on Deadline.