For years, I’ve watched the Pentagon’s innovation process with the same mixture of frustration and respect that a coach feels for a team with immense potential but a flawed game plan. So when I heard the news that the Defense Secretary is considering dismantling the JCIDS process, I didn’t see an act of destruction; I saw an opportunity for a profound transformation.

My career, from my time leading the U.S. Army’s Rapid Equipping Force (REF) in a combat zone to my work today, has been a master class in the painful realities of defense acquisition. The current system is a leviathan, built to generate a long list of requirements and a detailed plan for the “perfect” solution. It is a system that believes perfection can be found on a timeline measured in decades, not weeks. The result is a slow, methodical march toward obsolescence.

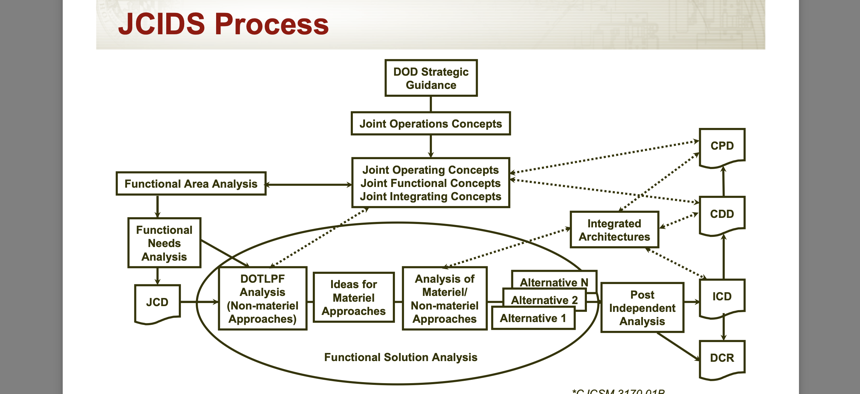

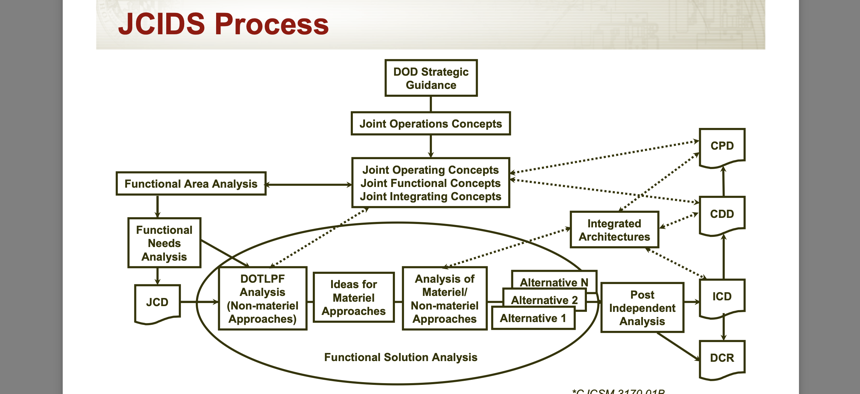

There will be those who warn of the immense cost of tearing down and replacing a system as entrenched as JCIDS—formally, the Joint Capabilities Integration and Development System, established in 2003 and most recently updated four years ago to centralize the development of requirements and metrics for the military’s acquisition efforts. They will point to the price tag of a new bureaucracy, the inevitable friction, and the risk of program disruptions. But we must weigh that against the far more catastrophic price of the status quo. The DoD’s own reports have documented numerous “cost overruns,” and while these financial burdens are significant, they are not the true measure of failure. The real cost of delay is not counted in dollars, but in lives. Every day a soldier waits for a critical piece of equipment is a day that increases the risk to a warfighter on the battlefield. As a former colleague and I once wrote, “Lives depend on our ability to rapidly recognize and address changes in the battlefield environment.” The cost of doing nothing is the cost of losing the next war.

We have a choice to make. We can continue a process that produces beautifully documented requirements for technology that is often out-of-date before it even reaches the hands of a soldier, or we can embrace a new methodology. The fundamental shift must be this: stop obsessing over requirements and start solving problems.

At the REF, we had to move at the speed of war, not the speed of bureaucracy. The enemy wasn’t consulting a committee to approve their next improvised explosive device. So we couldn’t wait for a “100-percent solution.” Instead, we adopted a standard of the “51 percent solution.” If a piece of equipment met just over half of its desired performance requirements, and it could get to the warfighter in time to save a life or achieve a mission, we considered it a success. We would then iterate and improve. This isn’t about accepting mediocrity; it’s about prioritizing speed and impact over a perfect, yet delayed, delivery. The bureaucracy always gets a vote, but it shouldn’t get a veto on our ability to solve problems on the battlefield.

My team and I built a repeatable model around this idea. We curated problems directly from the end user, and we engaged an ecosystem of innovators to help solve them. This approach became the foundation for the “Hacking for Defense” program, which we co-founded at Stanford 10 years ago. We took real, mission-critical problems from the Defense Department and U.S. intelligence community and challenged student teams to solve them using the “Lean Startup” methodology. Instead of producing more reports and glossy presentations, these teams were required to build prototypes and deliver working code.

The results have been astonishing. We’ve seen student ventures grow into successful companies that are delivering cutting-edge technology to the national security community, from flexible batteries for warfighters to constellations of satellites. These are companies that would have likely never entered the traditional defense contracting world. Why? Because the Pentagon’s greatest value proposition to the tech world isn’t its money—it’s its problems. By clearly articulating our most challenging mission needs, we can attract the best talent in the world to help us solve them.

The Secretary’s announcement is a call to action. It is a chance to fundamentally change our culture from one that values procedural compliance to one that champions ingenuity and results. This isn’t just about tweaking a process; it’s about embracing a new operating model for the 21st century. By focusing on real-world problems and empowering our people to find and deploy solutions with speed and urgency, we can ensure that our military remains the most capable in the world. It’s time to stop writing requirements and start solving problems.

Peter Newell, a retired Army colonel, is CEO of BMNT and a former director of the Army’s Rapid Equipping Force.

The post RIP, JCIDS. Let’s stop writing requirements and start solving problems appeared first on Defense One.