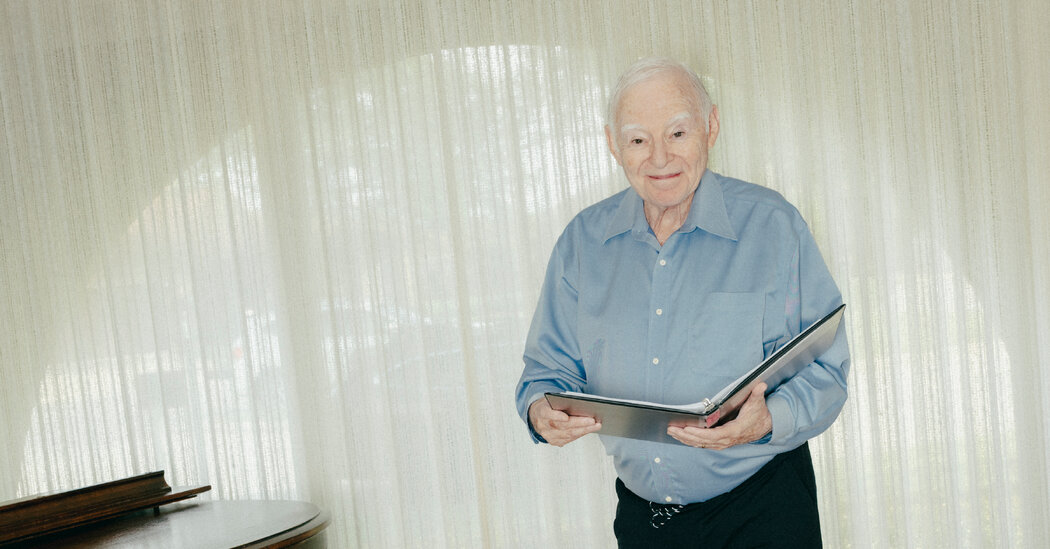

Ralph Rehbock, age 91 and a Holocaust survivor, has a lot on his calendar. On the first Friday of every month, he joins a group of older men at a synagogue outside of Chicago for a meeting of MEL: Men Enjoying Leisure. Every Friday afternoon, he performs classics from the 1930s and 40s with the Meltones, the club’s singing group. And he’s shared his story of escape from Nazi Germany with thousands of school children over the years, through his work with the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Education Center.

Leigh Steinman, 82, spends much of his time working on art projects with the children who live in his Chicago neighborhood and watching the Cubs play at Wrigley Field, which is just a block away. Mr. Steinman worked at the stadium as a security guard for 17 years before retiring at the beginning of the pandemic (his prior career was as an advertising copywriter). But he still walks over three or four times a week during the summer to see former co-workers and fellow fans.

Mr. Rehbock and Mr. Steinman are both considered “super-agers,” people 80 and up who have the same memory ability as someone 20 to 30 years younger. Scientists at Northwestern University have been studying this remarkable group since 2000, in the hopes of discovering how they’ve avoided typical age-related cognitive decline, as well as more serious memory disorders like Alzheimer’s disease. A new review paper published Thursday summarizes a quarter century of their findings.

Super-agers are a diverse bunch; they don’t share a magic diet, exercise regimen or medication. But the one thing that does unite them is “how they view the importance of social relationships,” said Sandra Weintraub, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, who has been involved in the research since the start. “And personality wise, they tend to be on the extroverted side.”

This doesn’t surprise Ben Rein, a neuroscientist and the author of the forthcoming book, “Why Brains Need Friends: The Neuroscience of Social Connection.”

“People who socialize more are more resistant to cognitive decline as they get older,” Dr. Rein said. And, he added, they “have generally larger brains.”

Researchers think that may be because socializing could help to protect against declines in brain volume that happen with age and isolation. Loneliness, which is particularly common in older adults, can increase levels of the stress hormone cortisol, and if cortisol is elevated for long periods of time it can lead to chronic inflammation. That, in turn, could damage brain cells and even increase the risk for dementia.

By being more social in old age, super-agers may avert some of the atrophy. An analysis included in the new paper backs this up: The brain volume of super-agers tends to be more on par with 50- and 60-year-olds than with their octogenarian and nonagenarian peers.

Another notable difference is that super-ager brains tend to have more of a special type of cell, called von Economo neurons, that is thought to be important for social behaviors and is only found in highly social mammals — namely apes, elephants, whales and humans.

All those von Economo neurons “probably help them build and maintain powerful, strong social connections and social networks,” said Dr. Bill Seeley, a professor of neurology and pathology at the University of California, San Francisco. And that may have “a far-reaching effect on their overall well-being and health.”

But, Dr. Seeley added, this is likely just one of “a whole suite of neurobiological advantages that puts them in such good shape at this stage in life.”

For example, almost all 80-year-olds have signs of Alzheimer’s disease in their brains (whether or not they have the condition), but some super-agers have little to none. In addition, in super-ager brains, the functioning of a neurochemical that is important for attention and memory is better preserved.

Dr. Sofiya Milman, a professor of medicine and genetics at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, studies healthy centenarians. She said that they also tend to be extroverted and “have a positive outlook on life.”

There is a “chicken and the egg” conundrum, though. A person with better cognitive functioning may be more eager to go out and socialize, compared with someone who feels like their memory is declining. “Whether it’s the socialization that leads to maintenance of better cognition, or whether it’s the better cognition that leads to more socialization, I think it’s still open to debate,” Dr. Milman said.

Unfortunately, forcing yourself to be more social probably won’t be enough to turn you into a super-ager. Dr. Weintraub said super-agers’ preternatural ability likely comes down to their genetics and biology, as well as their behaviors.

But to Mr. Steinman, the importance of seeing his neighbors and friends at the ballpark is clear. “I think the sociability of Wrigley Field and where I live, my block, that’s what’s kept me going all this time,” he said.

Dana G. Smith is a Times reporter covering personal health, particularly aging and brain health.

The post The One Quality Most ‘Super-Agers’ Share appeared first on New York Times.