Patrick Ryan, who grew up in the 1930s in County Tipperary, Ireland, understood that as the second son — and one of six children — he could not hope to inherit the family farm.

But that didn’t concern him. He had known since the age of 10 that he wanted to become a Roman Catholic priest.

In those days, he once said, nothing confirmed the social status of a family in rural Ireland more than “a bull in the field, a pump in the yard and a priest in the family.”

When he was 14, he entered a junior seminary run by the Pallottine order, also known as the Society of the Catholic Apostolate, which preaches comity and mercy. But even then, there were hints that he might someday find a calling more aligned with his natural proclivities.

Every night, he thrilled to stories his mother would tell about fending off the Black and Tans, the loathed British paramilitary forces (named for the uniform they wore), during the Irish War of Independence. An accomplished poacher even as a child, he was skilled at shooting and skinning wild rabbits. Later, in East Africa, he would shoot elephants for sport.

Posted there by the Pallottine order in the 1950s, Father Ryan built housing and hospitals and distributed pharmaceuticals. He learned how to excavate freshwater wells and pilot a plane, which he flew on daring medical missions.

But by the late 1960s, he was back in the United Kingdom, serving unhappily in an East London parish. He managed to extricate himself from that situation by telling his superiors that he needed to return to Ireland to care for his ailing mother. In Ireland, one of his tasks was to collect donations for the poor.

His superiors spotted a recurring shortfall, and he confessed. “I told them I was giving it to another organization,” he said in “The Padre: The True Story of the Irish Priest Who Armed the IRA with Gaddafi’s Money,” a 2023 biography written by Jennifer O’Leary.

That other organization, it turned out, was the outlawed Irish Republican Army.

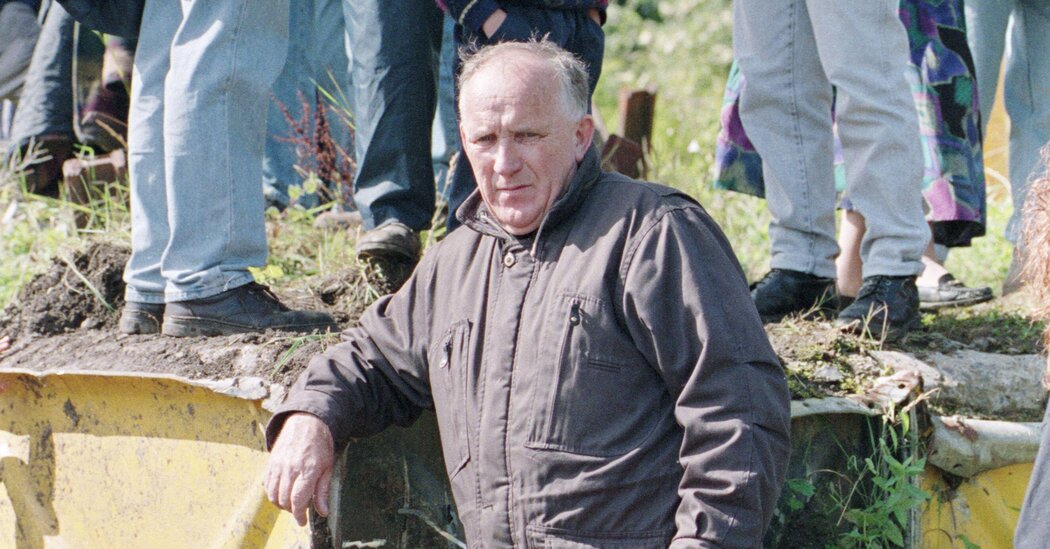

Father Ryan — who was known as the Padre in I.R.A. circles, but less benevolently in the British press, which referred to him as “the Devil’s Disciple” and the “Terror Priest” — would go on to become a major fund-raiser for the Irish resistance. He funneled money and guns to the I.R.A. from Libya, and turned the technical skills he learned in Africa to building detonators used to set off bombs that killed and maimed scores of people, and nearly killed Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

He died at 94 on June 15 in Dublin, according to Ms. O’Leary, who said she learned of the death from a nephew of his. He was never prosecuted.

Over the years, Father Ryan raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for weapons from the regime of the Libyan dictator Muammar el-Qaddafi. He also figured out how to take a simple timer intended to remind motorists to feed parking meters and re-engineer it into a device that could set off gelignite bombs. The bombs killed 18 British soldiers in Northern Ireland in 1979 and left two dead and dozens injured in Hyde Park in London in 1982.

Another bomb was planted in Mrs. Thatcher’s hotel bathroom in Brighton, England, where she was attending a Conservative Party conference in 1984. Though she was spared, the bombing killed five other people and injured more than 30, including one of her cabinet ministers, Norman Tebbit (who died earlier this month), and his wife.

“The only regret I have was that I wasn’t more effective, that the bombs made with the components I supplied didn’t kill more,” Mr. Ryan — he was defrocked in 1990 — told Ms. O’Leary.

He was remorseful, though, about having killed three elephants in Africa, he said.

Patrick Ryan was born on June 26, 1930, in Rossmore, a small village in the Irish province of Munster, to Simon and Mary Ann (Carroll) Ryan. His father was a farmer.

He attended St. Patrick’s College (now Mary Immaculate College), run by the Pallottine Fathers, in the town of Thurles, and was ordained in 1954. But by the time he was posted to a London parish in 1969, he was becoming bored with his vocation.

In Ireland in the mid-1970s, Father Ryan claimed to be soliciting contributions for the families of imprisoned Irish nationalists. Instead, he was raising money and procuring weapons for the terror campaign by Irish nationalists to drive the British from Northern Ireland.

He insisted that he never actually became a card-carrying member of the I.R.A.

“I joined the Catholic church,” he told Ms. O’Leary. “That’s bad enough.”

In 1975, Father Ryan moved to Benidorm, a town on the Spanish Costa Blanca. He enlisted an English girlfriend to smuggle cash for the I.R.A., which he collected from Libyan diplomats in Paris and Rome and deposited in a Swiss bank account.

In 1988, he was arrested in Belgium in connection with the deaths of three off-duty British soldiers in the Netherlands. Britain requested that he be extradited to face charges there.

But Father Ryan began a hunger strike, and the Belgians repatriated him to Ireland. The Irish government, arguing that he could not get a fair trial in England, also refused extradition, despite Mrs. Thatcher’s entreaties. (“Ryan is a really bad egg,” she told Charles Haughey, the prime minister of Ireland, with typical British understatement.)

By the late 1980s, Father Ryan had broken with the I.R.A. leadership, claiming that it had been compromised by British intelligence agents. In 1989, he ran as a candidate to represent Munster in the European Parliament, but won only about 6 percent of the vote. The next year, he was formally expelled from the Pallottine Order.

Ms. O’Leary described Father Ryan in an email as “one of the I.R.A’.s most significant intermediaries for money, as well as the main contact for many years between the I.R.A. and one of its main sources of weaponry and finance” — the Libyan government.

He was “a person of deep contradictions,” she wrote, who was capable of “an uncompromising pursuit of whatever orthodoxy he turned his attention to.”

He had elaborated on his role this way: “I set out to go around the world and discover the enemy of my enemy, the Brits,” he said, “and make their enemy my friend.”

Sam Roberts is an obituaries reporter for The Times, writing mini-biographies about the lives of remarkable people.

The post Patrick Ryan, ‘Terror Priest’ Who Aided the I.R.A., Is Dead at 94 appeared first on New York Times.