The intention of Rolling Thunder is a valuable and honorable one: to recognize the bravery and strength of veterans, and all those who fight for their countries in wartime. But the show’s framing and execution is bizarre and jarring: a rock and roll jukebox musical—it calls itself a “rock journey”—centered around the Vietnam War that wants you to bop in your seats as well as feel outraged and mournful. There’s nothing wrong with the split purpose, but Rolling Thunder feels more tribute band than profound tribute.

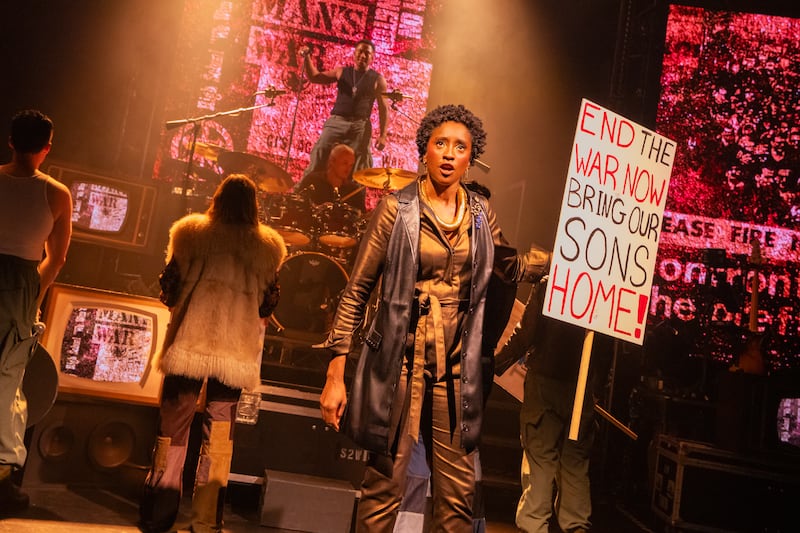

The disconnect between aim and result isn’t the fault of the performers—Drew Becker, Courtnee Carter, Deon’te Goodman, Cassadee Pope, Justin Matthew Sargent, Daniel Yearwood—who sing the familiar standards very well. But the uncomfortable collision of form and content was sitting in front of me: two people seated swaying happily in their seats to songs that are, in terms of how they are placed in the story, illustrating pain, death, disillusion, and loss. The material makes you want to do the impossible: rock out, then get patriotic, then sit still, think, be furious.

Rolling Thunder, at New World Stages through Sept. 7, is like a SingalongaVietnam. If you love the protest songs, and rock and soul of that time, you will enjoy all the renditions of such well-known numbers as “Born to Be Wild,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Gimme Shelter,” “Magic Carpet Ride,” “All Along the Watchtower,” “Nowhere to Run,” “Killing Me Softly With His Love,” “War,” and “We Gotta Get Out of This Place.”

The excellent band sits on a barely furnished stage with the performers, who act some scenes out as they mostly sing their way out of whatever emotional set-up each song is pegged to—it’s really a concert with some acting and props added. We progress haphazardly through a slice of love story, then a sortie to the Vietnamese jungle to see how the soldiers we initially meet are doing (the stage bathed in green light, the sound of helicopters). Then, snap: next song!

Yet the most powerful part of Rolling Thunder, with book by Bryce Hallett and directed by Kenneth Ferrone, indeed the best realized part of it, are less the familiar songs, but renderings of letters written by soldiers and their loved ones. Through those letters, and the way people convey the specifics of their days and nights, we hear stories of young love and separation; of mothers missing their kids; of kids missing their moms; of anger at people protesting the war rather than showing thanks to the soldiers.

Rolling Thunder seems nervous of its own depths, jumping from these letters to the songs, to American history, to patriotism, racism, and Nixonian gaslighting, to small character sketches that don’t make enough sense because we don’t spend enough time with the characters.

Each of these moments holds a kernel of a potentially fascinating story that goes underexamined: the nurse who serves in a warzone; the mom of a soldier being radicalized; the growing discontent and waning of idealism of those fighting; the sense of lives moving on, being torn apart, as the months go on. But there’s always another song to sing.

The show ends with the kind of panels of text we’ve become used to seeing on cinema screens that illustrate in stark statistics the terrible scale and cost of the Vietnam War, including the many soldiers still listed as missing. But this isn’t the end. The show—again it feels so tonally wacky—wants us to leave on a traditional musical theater high, so a rousing number sparks up to get us out of our seats, then there is another speech, then another song. Do we stay or go? It feels as if Rolling Thunder doesn’t know how to end, even if it wants, hopes, it has said something.

The post Maybe the Vietnam War Shouldn’t Be a Rock Musical appeared first on The Daily Beast.