Reuters

It hasn’t been an easy year so far for Jerome Powell. Unfortunately for the Fed chair, the second half is likely to be even tougher.

Powell faces a unique set of circumstances. President Trump’s tariffs threaten to raise consumer prices; at the same time, the labor market is showing some signs of cooling off.

The dual threat sets up an epic and delicate conundrum for Powell and the central bank as they go about setting policy, according to Robert L. Hetzel and Joseph E. Gagnon, two former Fed economists.

The Fed has two mandates that can sometimes be at odds: keeping inflation in check and supporting the labor market. Its main tool to is its ability to set short-term interest rates. When inflation runs too hot, it cranks up rates to slow demand. When the labor market starts to unravel, it cuts rates to boost borrowing and spending, and in turn, hiring.

The fed funds rate has been above 4% now for a couple of years as the central bank sought to hamper rising prices. Against most forecasts, it had done so successfully without throwing the economy into recession. It had then begun to cut rates in a bid to stick the soft landing.

Then Trump’s tariffs came along.

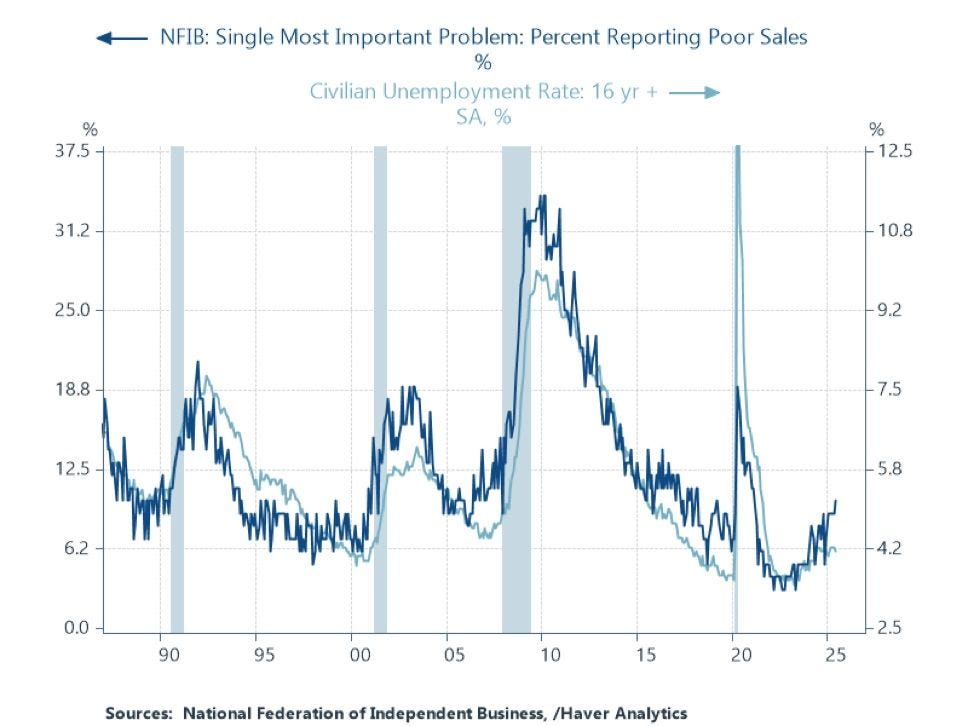

Now the Fed faces what is in many ways an unprecedented problem. On the one hand, some economists say the labor market looks set to soften further as job openings fall and as small businesses report slowing sales and falling hiring intentions.

For example, here’s a chart from Renaissance Macro Research economist Neil Dutta showing the close relationship between weak small business sales and the unemployment rate.

Haver Analytics

A slowing job market would usually not be accompanied by the threat of rising inflation, allowing the Fed to cut rates. But tariffs are complicating things. If the Fed jumps the gun with lowering rates, they could essentially be pouring gasoline on a fire that tariffs already threaten to stoke.

So far, Trump’s import taxes haven’t appeared to leak into consumer prices due to companies stockpiling inventory in late 2024 and early 2025. But eventually, those firms will have to start passing on higher prices to customers as inventories run low and tariffs start to eat into profits, according to both Gagnon, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and a former associate director on the Federal Reserve Board, and Hetzel, who worked as a researcher at the Richmond Fed from 1975-2018.

“At some point, they’re going to have to raise prices,” Hetzel said. “It always happens with a lag because nobody wants to be first and lose business.”

The challenge the Fed faces in moving too early is potentially allowing consumer inflation expectations to become unanchored, Gagnon said. Higher prices then become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Expectations of inflation directly lead into inflation because then people are expecting other people to raise prices, they’re quicker to raise their own prices, and the workers are quicker to ask for raises if they think there’s going to be another burst of inflation,” Gagnon said. “So you’ve got to keep that spiral from starting.”

The consequences of moving the other way and raising rates to ensure inflation stays low could also have disastrous consequences, Hetzel said, and spark a “financial panic” as bond rates surge.

“The Fed’s in a box,” Hetzel said.

The dilemma facing Powell is in some ways unprecedented because the last time the Fed had to face elevated tariffs was in the 1930s when the Smoot-Hawley Act was passed, Gagnon said. But a major difference was that back then, the economy was still recovering from the Great Depression and inflation pressures were not a concern, Gagnon said.

While there aren’t many direct parallels to the current environment, both Gagnon and Hetzel said tariff-driven inflation could behave like price gains in an oil shock. That is, prices will rise one time and then settle.

The dangers of taking that approach, however, is the Fed runs the risk of letting consumer inflation expectations float away. This might be an especially high risk given that we’re only a few years removed from the post-pandemic inflation surge, which is fresh in consumers’ minds. It’s still fresh in the minds of Fed leaders as well, as they had infamously insisted the episode would be “transitory.”

“The problem is that we’ve just had a big burst of inflation that they thought was temporary and turned out to be more permanent,” Gagnon said. “And so people might be more primed to react to higher prices, and to think it’s going to be another bout of inflation for two or three years.”

The post 2 former Fed economists say Chair Jerome Powell is facing an epic conundrum appeared first on Business Insider.