In recent years, the Western public discussion has been full of laments over the collapse of the so-called rules-based international order established in the aftermath of World War II. Some blame Russian President Vladimir Putin; others blame U.S. President Donald Trump or Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Indeed, all these individuals have contributed significantly to the disintegration of the global order.

Outside of the West, however, concerns about the hypocrisy and double standards of the postwar international order are nothing new. Indeed, leaders of postcolonial countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East consistently castigated the self-serving nature of this order from the moment of its inception.

Not only did these states chafe at this order, however, but they also attempted to offer an alternative vision. One of the most famous attempts came with the 1955 Asian-African Conference, widely known as the Bandung Conference. It represented the global south countries’ quest for agency in international affairs, offering a powerful critique of the emerging global order and an alternative vision grounded in a more egalitarian set of values.

Today, middle powers from outside the Western world are again demanding a greater voice in global politics. In expressing their dissatisfaction with the international order, they have often echoed Bandung’s rhetoric and tone. But they have put less emphasis on the principles that were central to the conference’s global vision. To succeed where Bandung failed and have a greater impact on global politics, middle powers must revive values of the Bandung Conference to rebuild a more just and enduring international order.

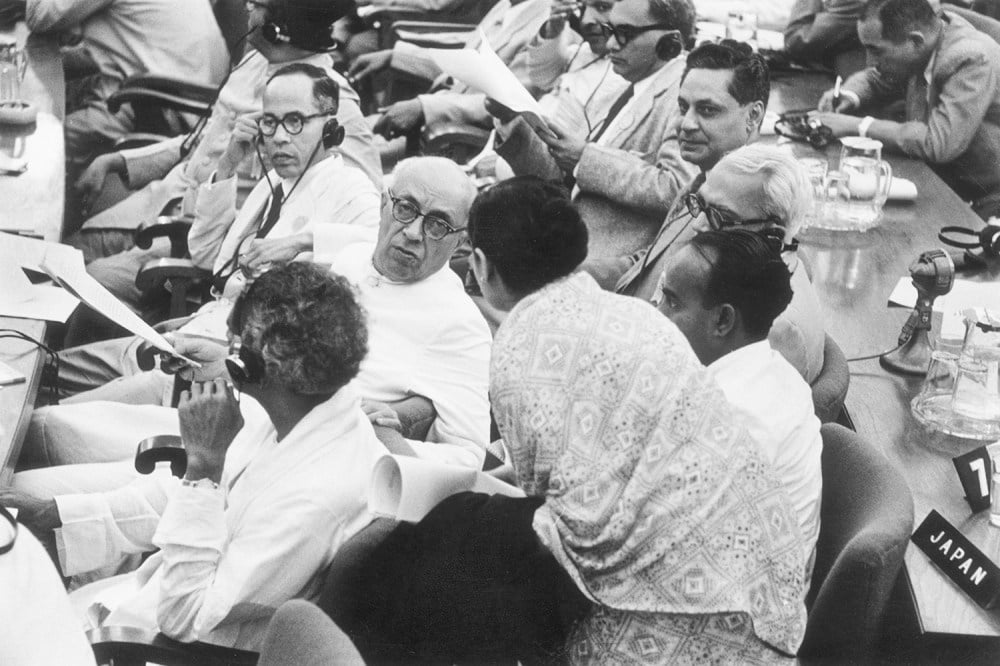

The Bandung Conference, which took place in Bandung, Indonesia, 70 years ago this year, was one of several international gatherings from the 1940s into the 1960s that helped popularize the ideas of nonalignment as well as the so-called third world or global south as a political force. Not only did conferences such as Bandung showcase non-Western versions of multilateralism, but they also boosted alternative visions of global political agency.

This new sense of agency was reflected in the fact that such conferences took place outside of Europe and criticized the European-dominated international status quo. In his opening speech, Indonesian President Sukarno, a key figure and the host of the Bandung Conference, argued that only a few decades prior, leaders of Asian and African nations had to travel to other countries and continents to discuss their own matters. Now, they were meeting in their own countries to address their issues. With his speech, Sukarno insisted that Afro-Asian states become the subject of history and take their destiny into their own hands.

Crucially though, the leaders at Bandung believed that their agency could best be achieved by embracing new norms for global politics. They codified this in their embrace of 10 principles, commonly referred to as the Bandung spirit. The first principle was respect for fundamental human rights and the United Nations Charter. Others included rejecting the use of force against any country, resolving international disputes through peaceful means, respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations, and recognizing the equality of all races and nations. Sukarno himself spoke of the need to mobilize the “moral violence of nations” in the service of peace.

In the face of crises such as those in Ukraine and Gaza, non-Western powers are again trying to play a greater role on the world stage. But despite the obvious similarities to the 20th century Non-Aligned Movement, they are going about it differently: Amid different global conditions, they have downplayed norms and values, avoided collective advocacy, and taken a regional rather than global approach international politics. As a result, middle powers are now more willing to accommodate spheres of influence while shying away from providing global or regional public goods.

The systemic conditions that gave birth to Bandung and later to the Non-Aligned Movement have clearly changed. Decolonization drove leaders in Bandung to coalesce around principles of equality, law, and justice. The bipolar nature of the Cold War led them to push for the creation of a third pole, which eventually became known as the Third World.

But this global shift does not explain alone the decision to abandon Bandung’s values. Today, amid the rise of the BRICS bloc (comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and other recently added members), pragmatism and self-interest prevail. BRICS leaders are quick to criticize the global order, but they are slower to articulate a shared political project to remake the world. Their multialignment, which informs their multilateralism, is heavily focused on hedging. Furthermore, it does not necessarily reject a United States vs. China framing of the international system. While nonalignment historically often meant rejecting a world that was either Western- or Soviet-centric, today’s BRICS increasingly risks becoming China-centric. Indeed, China is one of the key actors in the bloc.

Where Bandung and the Non-aligned Movement had a clear moral stand on sovereignty, territorial integrity, and independence, BRICS members were reluctant to take a firm stand when one of them, Russia, recently invaded its neighbor, Ukraine. While countries in the global south have largely taken a more principled stance on Gaza, middle powers in the Middle East have hardly used real leverage on Israel.

-

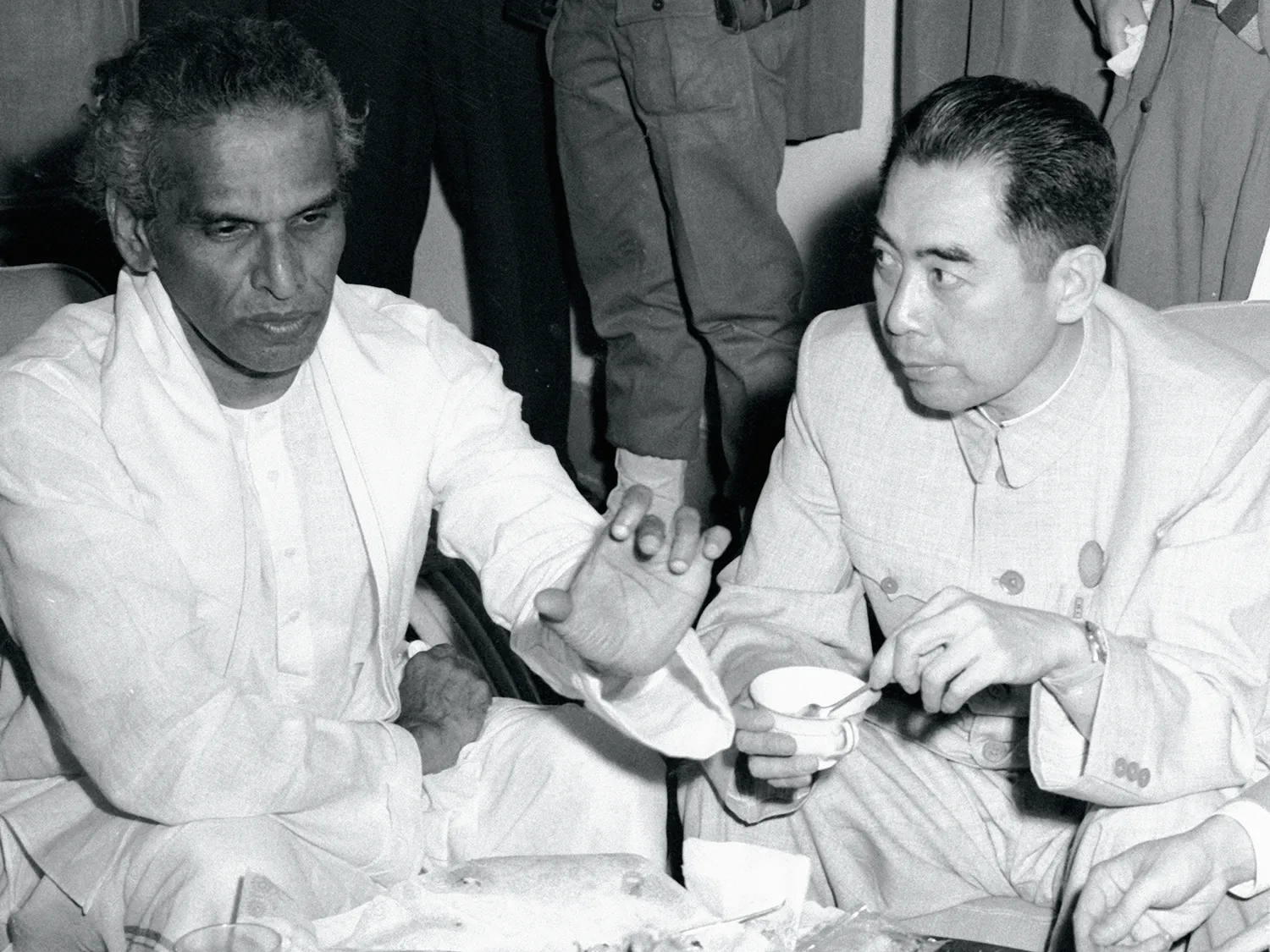

In this black-and-white photo, Menon gestures as Zhou drinks from a small cup and leans close to listen. Both men sit cross-legged on the ground with the tea set between them.

-

Hassen, wearing white and a hat, leans close as he confers with a taller Nasser, who wears a military uniform and holds a teacup.

Where collective advocacy was crucial in Bandung, today’s internationalism is driven by a form of strategic selfishness. Middle powers have also embraced their own versions of “America First”—call it India First, Indonesia First, or Saudi Arabia First. This approach is fundamentally at odds with a version of multilateralism that interprets national interests not as a one-shot game, but as long-term investments in institutions and partnerships.

Today, middle powers will have to make a choice. Without collective advocacy rooted in shared values, middle powers cannot present a credible alternative to remake the global order. Without shared norms, the glue binding these countries together is weak, and consequently, so is their influence. Despite not being its architects, the participants who gathered in Bandung in 1955 embraced the U.N. Charter and its human rights provisions. The 10 Bandung principles reflect the participants’ ownership and interpretation of a multilateral order embedded in international law. They attached great importance to the United Nations’ General Assembly, which they viewed as being more representative and inclusive.

Bandung’s attachment to principles is particularly valuable when superpowers have an inherent aversion to norms and laws that constrain their power. This was sometimes the case during the Cold War, but it is even truer today. The United States and China possess the size and power to operate in a world devoid of international law and norms. However, middle powers stand to lose in this world.

Admittedly, international law cannot form the sole basis of a functioning multilateral system. But without some version of it—particularly international humanitarian law—and without organizations such as the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court (ICC), and the World Trade Organization, all countries, and especially small and middle powers, will be worse off. Selective adherence to international law and norms, such as Germany’s tendency to disregard the ICC’s arrest warrant against Netanyahu, will only further undermine the legitimacy of the so-called rules-based international order that European middle powers are purportedly supporting.

The need for a broader vision is also reflected in the geographic focus of middle powers today. Bandung focused on the nature of the then-global order, whereas today’s middle powers are more concerned about their regional orders. The Bandung Conference and similar platforms concentrated on utilizing the U.N. General Assembly to advance global economic and legal goals. In contrast, many middle powers filter their global posture today through the lenses of their regional aspirations and priorities. For instance, many middle powers prefer to view the Russia-Ukraine conflict as a regional war in order to avoid taking sides and to maintain relations with Russia.

At Bandung, the rejection of bipolarity led to the rejection of sphere-of-influence politics. Many also felt uncomfortable with the pole-centric view of the world. Today’s middle powers, in contrast, appear to be more accommodating toward sphere-of-influence geopolitics, despite the fact that this would undermine equality and agency of small and midsized states. Perhaps countries within the top tier of the middle powers, such as India, may harbor the ambition deep down to be upgraded one day into the superpower category, with a sphere of influence of their own.

Yet this reduces the international system to an amalgamation of regionalized constellations, each with their respective regional hegemon. The “global” in the global order will increasingly lose its relevance, with dire consequences for the provision of international public goods, such as those necessary for climate action, debt relief, health, and finance.

Transactionalism and opportunism will not work for middle powers. Indeed, despite its principled aspirations, these ultimately proved to be the undoing of the first Bandung Conference. Following the 1955 gathering, a second conference was planned for a decade later. But it never materialized, mainly due to the internal instability of the participating countries and their differing foreign-policy interests.

To fend off a G-2 world dominated by the United States and China, and to prevent the current global disorder from deepening, middle powers should live up to Bandung’s values rather than abandon them. To effectively work together, they should adopt a global perspective and champion fair and consistent rules. With Trump driving the final nail into the coffin of the trans-Atlantic alliance, many European states have had to rediscover their status as middle powers.

This presents an opportunity for middle powers in both the global south and global north to unite in defense of a robust and norms-based multilateral order. This could unleash a true alternative to the sphere of influence geopolitics subscribed to by Russia, China, and the United States.

The post Bring Back the Spirit of Bandung appeared first on Foreign Policy.