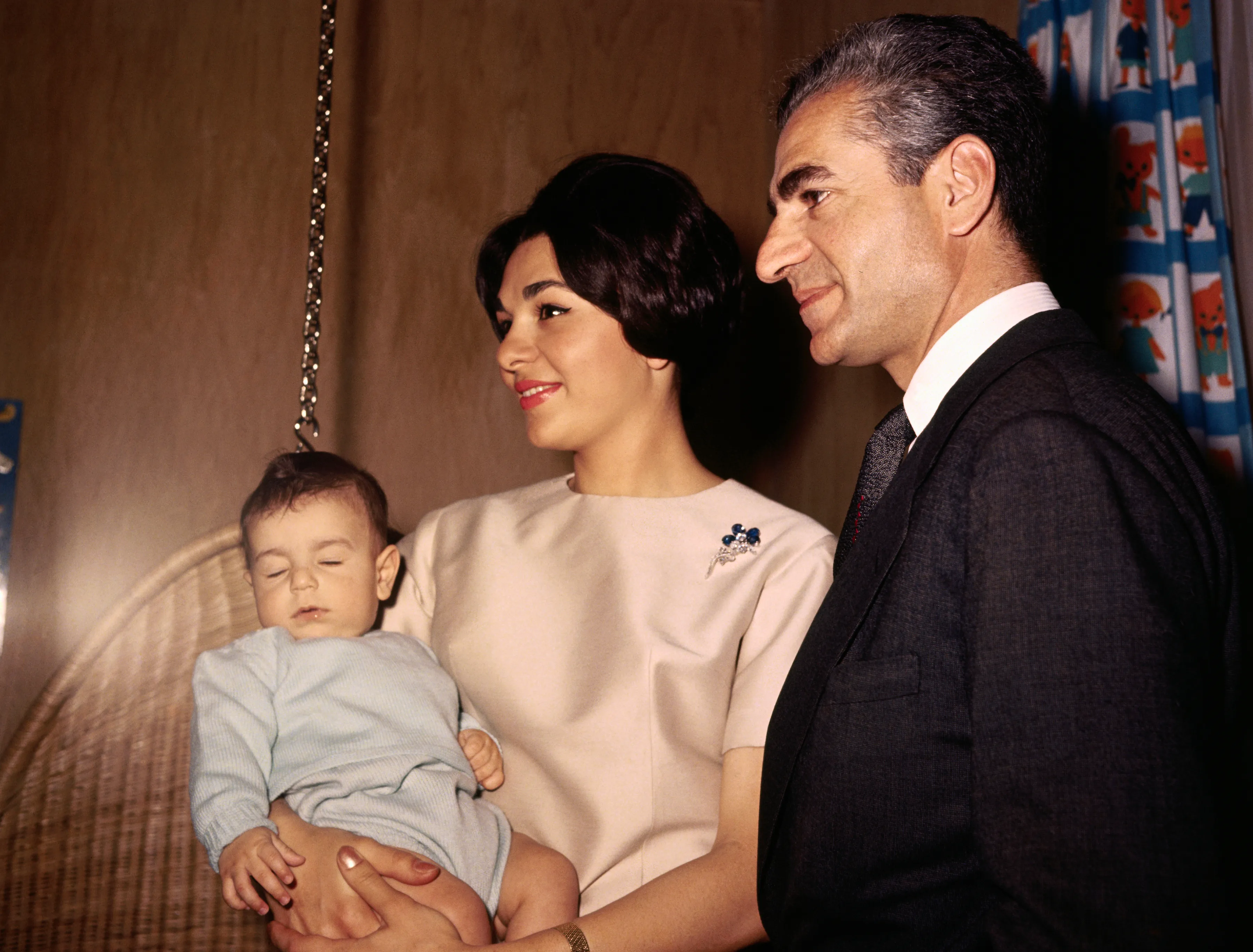

The aesthetics are compelling. Black and white photos of a Tehran University lecture hall with men and women seated side by side wearing the best of 1950s European fashions. Young girls—unveiled and in public—cheering to welcome the French president. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran, in a crisp suit, alongside his third wife, Empress Farah Pahlavi, who sparkles with beauty and grace.

With the latest U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran, talk of regime change has gone from discredited to imaginable within the Western public sphere. Reza Pahlavi, the exiled son of the deposed king, wants to lead the transition, confidently issuing plans for his first 100 days after the fall of the regime. Some prominent publications are even asking whether he may indeed be the solution to Iran’s ills.

Following the disastrous U.S. interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the well-known consequences of Iran’s 1953 coup, how is the possibility of bringing back another Pahlavi to the throne even up for discussion? The cruelty and corruption of the current Iranian government are certainly a big part of the answer. But carefully cultivated Pahlavi nostalgia also plays a key part. Images of unveiled, stylish women in 1970s Tehran have been crucial to painting an idealized portrait of a modern, peaceful, and prosperous Iran supposedly stolen away by the mullahs.

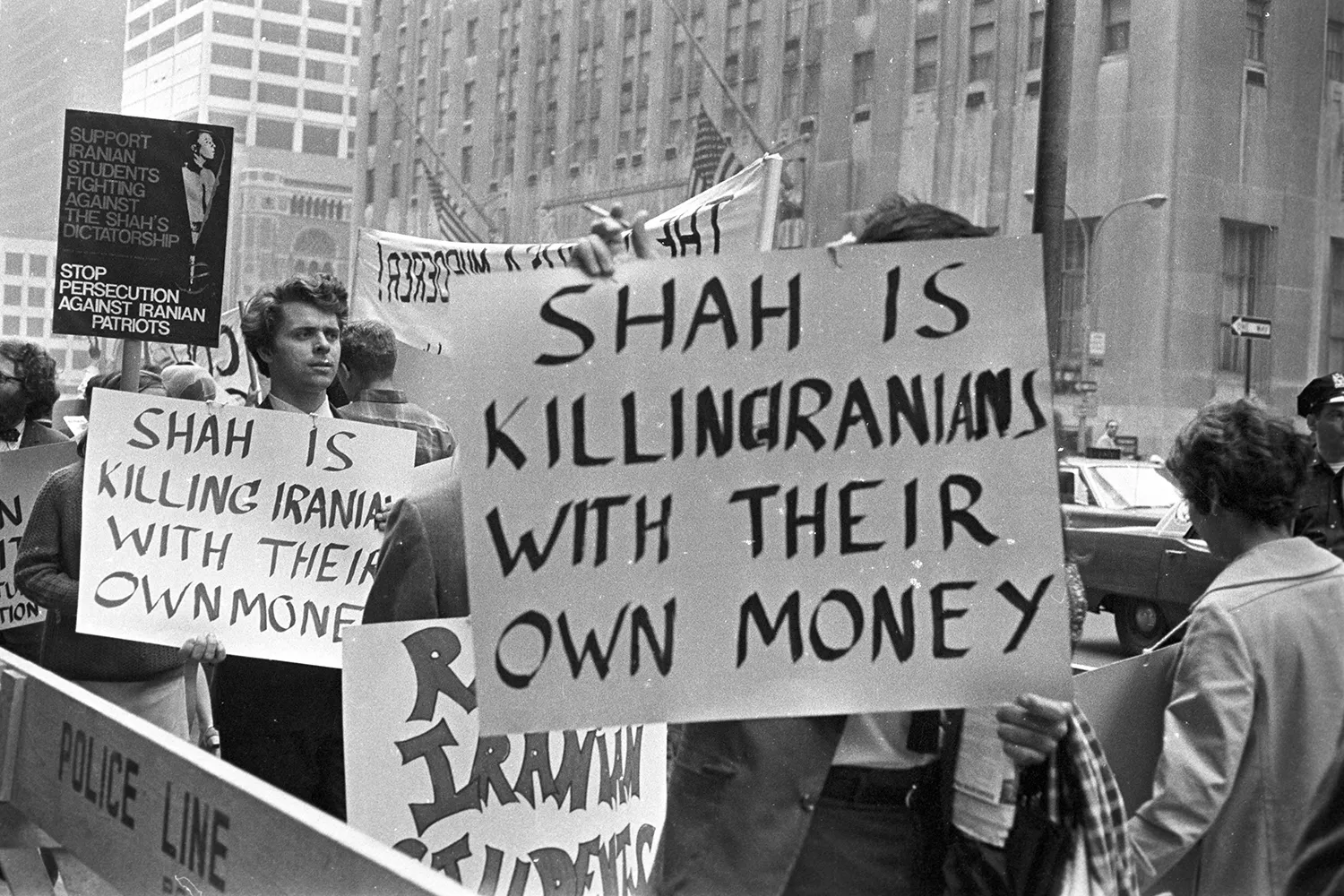

Critics, of course, have been quick to point out that social media celebrations of pre-revolution Iran hide the realities of a dictatorial regime that tortured dissidents while its monarchs cavorted with European elites and feasted on Maxim’s desserts. For every photo of Farah posing with Andy Warhol, the thinking goes, there is a hidden image of death, pain, and squalor.

Criticism of the shah’s authoritarianism is eminently fair. Ironically, though, it often accepts the same assumption put forward by the shah’s apologists: that the Pahlavis were straightforward Westernizers, secularists who forcefully tried to drag Iran into full alignment with the West. The real story was much messier. As scholars like Ali Mirsepassi and Zhand Shakibi have shown, the Pahlavi’s self-presentation was never straightforwardly pro-Western or secular.

Increasingly during the 1970s, the Pahlavis relied on traditionalism, Islam, and mystical claims to legitimacy—forces that would later feed the revolution that toppled them. Farah herself was a leading sponsor of traditionalist thinkers who criticized Western materialism and sought to promote Iran as the shining example of Islamic spirituality. The full story of her reign shows her to be not merely a feminist icon or Persian Marie Antoinette, but rather a more complicated and cautionary figure entirely.

It’s no surprise that women populate the most striking “Iran before the Revolution” clickbait photo essays. As scholars who examine gender in foreign relations have long observed, women often symbolize the nation, their status being used as a marker of culture and civilization. While the forcefully veiled, “oppressed” Iranian woman is the primary symbol of the current Iranian regime’s awfulness, pro-monarchists seem to find the perfect symbol of their nostalgia in 1950s Dior gowns and 1960s miniskirts. In this context, the undeniably glamorous Farah continues to serve as a symbol for pre-revolutionary Iran’s pro-Western orientation.

If the 86-year-old former monarch, who currently divides her time between Washington and Paris, is following social media, she must be experiencing déjà vu. As the shah’s third and final wife, she represented Iran to the world from the moment she got married. After all, between 1959, when she first got engaged to her twice-divorced husband, until 1979, when they fled together into exile, the empress was at the center of a running debate about authoritarianism, Islam, and democracy. Supporters—including the Iranian state—promoted her as the perfect embodiment of Iran’s proper progress under righteous royal rule. Detractors, meanwhile, maligned her as a distraction, a “painted doll” who hid the realities of the Pahlavis’ corruption, cruelty, and servitude to imperialism.

Much like Empress Soraya before her, Farah initially became a symbol of Iran’s pro-Western modernization in global media. Specifically, she was associated with the shah’s ambitious development project, the White Revolution, which he launched in 1963. The program’s initiatives included massive infrastructure projects, land redistribution, public health campaigns, profit-sharing for workers, new literacy programs, and women’s suffrage. Domestically, these measures brought real shifts: Per capita incomes rose, old feudal ties weakened, and cities expanded rapidly. Abroad, they gave Iran—and its royal family—a much higher ranking on the West’s modernity scorecard, transforming the country’s image in just a few years.

Farah’s time in the limelight coincided with boom years for the world’s illustrated press, and the capitalist Western media gave the Pahlavi regime an image-driven platform that helped its national branding flourish. Western magazines listed the empress among the world’s best dressed women—sometimes over style icons like Jackie Kennedy Onassis—and offered the Empress’s famous hairstyle for adoption. However, they also praised Farah for staying “as simple and unaffected as when she was a commoner-school girl.” Betty Friedan, the leading voice of liberal feminism in the United States, called the empress “a feminist” in the pages of Ladies Home Journal, pointing to her understated makeup and busy schedule as proof. Such images of simplicity and working motherhood wrapped the monarchy in the aesthetics of Westernized femininity. Predictably, these images have found new life in today’s “Iran before the Islamic Revolution” meme wars. They imply that a renewal of Pahlavi rule will mean liberal development, respect for women’s rights, and pro-Western policies.

Inevitably, the critiques of these images also have their roots in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1967, the Iranian leftist exile Bahman Nirumand argued that while the monarchy staged impressive public diplomacy abroad, most Iranians still faced poverty and the brutal repression of SAVAK, the shah’s notorious CIA-trained secret police. The polished imagery of the Pahlavi White Revolution—with the youthful, glamorous empress at its center—was, in Nirumand’s eyes, purely a distraction from harsher truths on the ground. As he put it bitterly, “To make up for it, Iran has a beautiful Empress.”

Nirumand’s critique found sharp echoes in a scathing open letter from German journalist and Red Army Faction member Ulrike Meinhof, which circulated among student activists during the shah and empress’s 1967 visit to Germany. Meinhof juxtaposed glossy magazine stories about Farah’s privileged life with Nirumand’s evidence of corruption and state violence, mocking the empress as an Eastern Marie Antionette. For example, she sneered at Farah’s wistful comment about craving Iranian sweets after a stay in Paris: “You see, most Persians aren’t hungry for sweets, but for a piece of bread.”

For critics, this image of gendered and classed corruption was captured in the concept of gharbzadegi. The word, meaning “West-struckness” or “Westoxication,” was the title of a book in 1962, after which it quickly gained currency in vernacular discussions about the shah’s female family members.

Inevitably, the truth was more complicated. After all, the man who coined the term gharbzadegi was on the Pahlavi payroll: Heideggerian philosopher Ahmad Fardid was one of several intellectuals who critiqued Western secularism and modernity, advocating for a return to Shia authenticity. But before throwing his intellectual weight behind the Islamic revolution, Fardid regularly collaborated with the monarchy, explaining the shah’s one-party ideology to the people and appearing on state TV networks to malign the false worship of the West.

As a leading sponsor of cultural initiatives across the country, Farah played a key role in calling for an authentic Iranian authenticity that was not only royalist and Persian but also Shiite Muslim. Farah was crowned empress and designated regent in 1967. As such, she did not simply have the shah’s ear. She also ran her own special bureau with hundreds of employees, and oversaw countless artistic, cultural, educational, welfare, and public health initiatives. In the early 1970s, she also became more actively involved in foreign policy, notably representing Iran in China shortly after the shah’s 1972 visit to the Soviet Union.

As accusations of gharbzadegi spread, Farah continued to emphasize that she believed in developing Iran in accordance with “Iranity.” She warned about the dangers of superficial modernization, and voiced concerns about Iranian youth’s admiration for all things Western in her memoirs and interviews: “[C]ertain superficial aspects of Western culture and civilization—not their true values—can be extremely dangerous, particularly for young people, because they copy unthinkingly.” Ironically, this resembled the very critique the opposition leveled against the Pahlavis: that they privileged superficial modernization over substance, showcasing flashy projects and fashionable women, while ignoring the real needs of the population.

The empress also sponsored intellectuals who advocated for Islamic Iranian authenticity, including the philosopher Seyyed Hossein Nasr. In 1974, she directed Nasr to establish the Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy, then later appointed him director of her private bureau. For Nasr, and other regime-aligned scholars such as Fardid, Henry Corbin, and Dariush Shayegan, Iranian Shiism held the roots of an authentic mystical vision that could heal the wreckage of Western modernity. Nasr saw his role as reclaiming the lost essence of Shia mysticism and limiting Western influence over Iran. He has subsequently said, “long before Khomeini attacked the West, I attacked the West in Iran.”

Farah’s husband was equally committed to the language of religious and national authenticity. The shah was often cast as a materialistic technocrat who reportedly “devoured [military] manuals in much the same way as other men read Playboy.” But, starting with his first autobiography in 1961, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi positioned himself as a mystically guided, fully Muslim and Iranian leader. In his final book, Answer to History, he doubled down on this, calling the university students who rebelled against him “soulless.” “I am a religious man, a believer,” he emphasized, “I follow the precepts of the sacred Book of Islam, precepts of balance, justice, and moderation.”

In fact, even the shah’s much-celebrated “granting” of rights to women was less a product of his own impulses than the persistent efforts and advocacy of Iranian feminists. According to Iranian politician and women’s rights activist Mahnaz Afkhami, in the lead-up to the 1967 family law reform, the shah offered no support or direction, only cautioning “that no topic that contradicts the explicit text of the Quran should be discussed, especially the topic of inheritance.” The shah showed little hesitation in dismissing women’s liberation and equality as misguided Western ideas. In an interview with Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci in 1973, he said: “This women’s lib business, for instance. What do these feminists want? What do you want? Equality, you say? Indeed! I don’t want to seem rude, but … you may be equal in the eyes of the law, but not, I beg your pardon for saying so, in ability.”

Although he was returned to power in a coup backed by the United States and the United Kingdom, the shah did not always act according to the wishes of his geopolitical sponsors. In his meetings with Western leaders, he bristled at being read as a pliant secularizer on behalf of the United States. In 1962, he told President John F. Kennedy that “America treats Turkey as a wife, and Iran as a concubine.” Nor was the White Revolution a straightforward pro-Western project. The shah launched it after dismissing liberal Prime Minister Ali Amini, whom he considered a favorite of Washington. Backed by oil revenues, he used these reforms to try to ease discontent among diverse groups, present the monarchy as the engine of “revolutionary” modernization, and entrench his one-man rule. Under President Richard Nixon and Kissinger, the shah was also able to direct a more independent foreign policy. To this day, some Iranian monarchists insist, conspiratorially, that this was why the West secretly backed the Iranian revolution.

Despite what critics and apologists still believe, the Pahlavi project was not simply Westernization by fiat. Instead, the monarchs offered an ultimately unstable blend of imitation, reaction, mysticism, and authoritarianism. The “pro-Western” shah wasn’t always pro-Western. Nor was he a feminist. As for the glamorous modern empress in those photos, she helped fund many of the anti-Western and traditionalist ideologies that we now associate with the Islamist republic—even as the opposition painted her as a Westoxicated Marie Antionette.

Farah’s story is another reminder of how celebrating supposedly pro-Western dictators or modernizing monarchs can backfire. Romanticizing her family’s rule isn’t just harmless nostalgia—it’s selective history that props up reckless policies in the present.

The post Empress Farah Pahlavi and the Myth of the Secular Shah appeared first on Foreign Policy.