The Rev. John Odams, pastor of the oldest Baptist church in Boston, was building shelves for the American Baptist archives on a Saturday in May when a volunteer brought him something unusual that she had just found in a box.

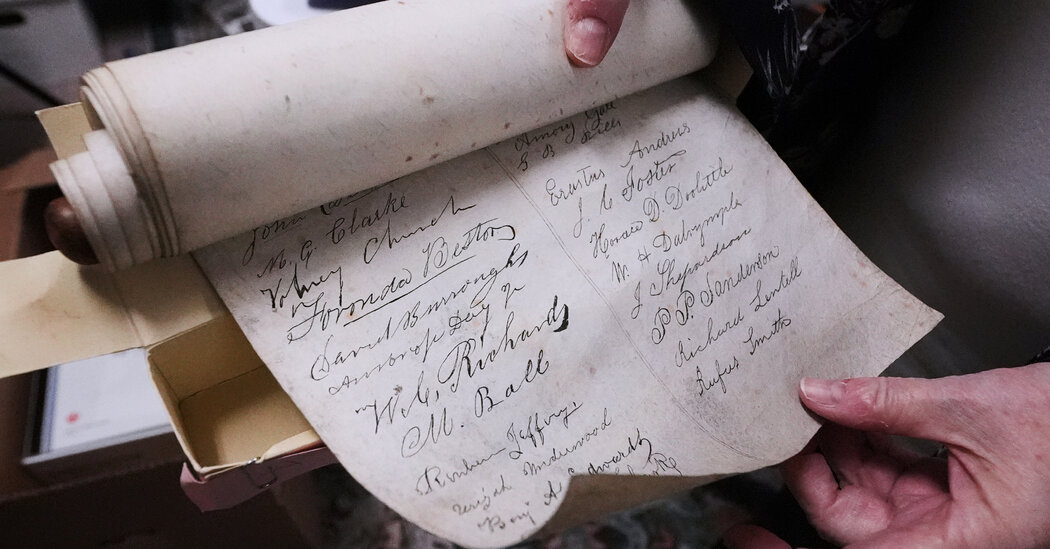

“It looked like a prop from a Christmas pageant or something, a little scroll rolled up — but then we opened it,” Mr. Odams said. He recognized a name on the list of signatures as that of the pastor who led his church, the First Baptist Church of Boston, in the 1800s. He knew instantly that this was a momentous document from Baptist history — one that was thought to have been lost.

The scroll was handwritten in 1847, just two years after Baptists in the United States split, with the Southern congregations breaking off over their Northern counterparts’ condemnation of slavery.

Using forceful language, 116 Baptist ministers in Massachusetts had signed their name to what they called “A Resolution and Protest Against Slavery,” condemning the system as “entirely repugnant.”

The document had largely been forgotten until the Rev. Diane Badger, an American Baptist minister in Massachusetts who works to record and preserve the Church’s history, read a copy several years ago in a book that was published in 1902. She searched in vain for the scroll in archives across New England but did not find it. The discovery in May, reported earlier by The Associated Press, was a surprise, as was the fact that the 178-year-old scroll was in pristine condition.

“The ink on the signatures was really strong,” Ms. Badger said. The discovery has elated American Baptists and faith leaders in Massachusetts, who say they draw inspiration from the document, which is emblematic of the nation’s evolving attitude toward slavery.

At the time, the increasingly forceful stance by the Baptist ministers in Massachusetts against slavery reflected the widening divide between the North and South, said Deborah Van Broekhoven, a retired professor of early American History and former executive director of the American Baptist Historical Society.

That national breach would become so wide that, 14 years after the document’s signing, it would lead to the Civil War.

“I think the document embodies the whole story of the struggle,” Dr. Van Broekhoven said. “The struggle that people had to reach the conclusion that slavery was their problem, their responsibility, that their morality was called into question.”

At the height of slavery in the South, the Baptist ministers declared, “Under these circumstances we can no longer be silent.” Slavery, they said, was “an outrage upon the rights and happiness of our fellow men, for which there is no valid justification or apology.”

Several ministers who signed the resolution led churches that still exist. Ministers of several Black churches also signed, and some would have had freed slaves in their congregations. It is possible that at least one of the men who signed was a Black minister. The authors describe themselves in the text only as “freemen” with “enlightened consciences.”

Other signatories were noted abolitionists. Nathaniel Colver, the first minister of Tremont Temple, a church believed to be one of the first racially integrated in the United States, helped found the American Baptist Anti-Slavery Society in 1840.

Followers of that 19th-century Baptist tradition are now known as American Baptists, a denomination of Christianity with congregations all over the world. It is still considered more progressive than Southern Baptists, who lean conservative.

Some faith leaders in Massachusetts, even those who are not Baptist, said they saw themselves as carrying on the tradition of spearheading progressive social causes that began more than 150 years ago with the Baptist support for abolition. American Baptists, for example, ordain women as pastors and do not outright condemn abortion.

Laura Everett, the executive director of the Massachusetts Council of Churches, a coalition that includes Baptist churches, said in an interview that “this document helps us draw courage to stand up and speak again.” The group has spoken out against the Trump administration’s policies and joined with other religious groups this year to sue the Department of Homeland Security for carrying out immigration raids in houses of worship.

The Rev. David Wright, a Baptist minister in Boston, said that the Baptist ministers showed bravery in 1847 in attaching their names to such forceful language. He said that it was “electric” to know that such a document existed and that it was so well preserved.

Mr. Wright said he saw his work with BMA Tenpoint, a coalition of churches, nonprofits and other faith-based organizations in Greater Boston, as a continuation of the Baptist tradition and the tradition of Black churches. The organization grew out of the 1960s civil rights movement in Boston that was led by interdenominational Black clergy and has since worked to tackle “the racial, social and economic injustices” that the city’s Black communities face, including gang activity, youth violence and food insecurity.

“I think more churches in Boston and in Massachusetts are more progressive than churches and other places,” Mr. Wright said. “Some people see that as a positive, some people see it as a negative. I just see it as it is.”

Aishvarya Kavi works in the Washington bureau of The Times, helping to cover a variety of political and national news.

The post Discovery of 178-Year-Old Baptist Antislavery Document Elates Faith Leaders appeared first on New York Times.