“Where’s your emergency?” the 911 operator asked.

“Rodeway Inn on Woodstock Avenue in Rutland,” the caller replied, her voice barely under control. “My boyfriend lay down for a nap and he’s not breathing.”

The operator began explaining how to perform CPR, asking whether the boyfriend could be lowered to the floor. The caller, Ginger Parker, was immediately distracted: Their 18-month-old daughter had crawled on top of the still body.

“Honey, get off of him — please!” Ms. Parker pleaded, explaining to the operator that the toddler just wanted to help.

The man she was trying to save that evening in August 2012 was David Blanchard III, who worked the night shift at Rutland Plywood in the small Vermont city. The 28-year-old with a neat goatee, dark hair and kind face lay on his back in a dingy motel room strewn with clothes, a sheet, children’s toys and books, and a pink rubber duck.

The operator told Ms. Parker to place the heel of one hand on the center of her partner’s bare chest, the other on top and to intertwine her fingers. “Push hard and push fast,” the operator said. “You’re going to do it a hundred times a minute.”

Soon, Ms. Parker heard gurgling. “Oh, my God. I’m so sorry,” she said. She sounded frantic, exerting herself, breathing heavily.

The operator asked whether Mr. Blanchard had been drinking or taking drugs.

“Uh, no — no,” Ms. Parker said.

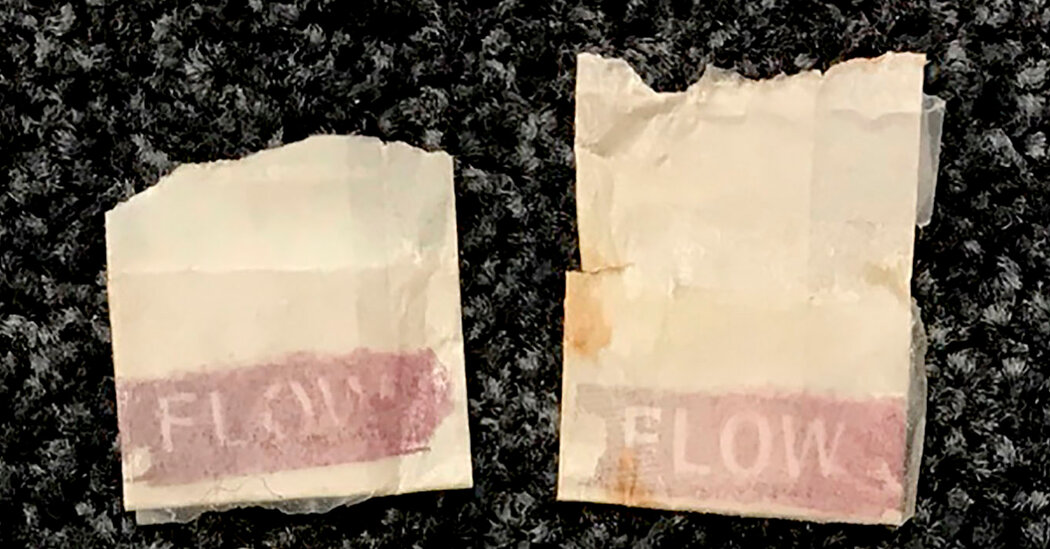

But when medics later pronounced Mr. Blanchard dead in Room 132, they saw a track mark on his right forearm. In a diaper bag, Rutland police officers found a small zippered pouch containing used hypodermic syringes and empty glassine heroin bags.

Four bags were stamped with a brand name in capital letters: FLOW.

Mr. Blanchard’s death set in motion a yearslong hunt for the criminals who had supplied the fatal dose. It touched people powerless in the face of addiction, and the people who loved them. It laid bare the link between Rutland and the Tremont section of the Bronx, communities separated by hundreds of miles but gripped by a common scourge: the multibillion-dollar global heroin trade.

The Flow case encompassed scores of investigators, prosecutors and dealers and led to arrests, trials and convictions. For Ms. Parker, it provided a modicum of justice and mercy, but no simple redemption.

In 2012, Mr. Blanchard’s heroin overdose was one of 50 opioid-related deaths in Vermont. Less than two years later, Gov. Peter Shumlin devoted his State of the State address to what he called “a full-blown heroin crisis.” By 2016, overdose deaths had doubled, to 106, and five years later, they had doubled again.

Today, a different opioid — fentanyl — drives an overdose crisis that has stubbornly persisted in the years since Mr. Blanchard died. But the networks of dealers and drug users connecting communities all over America in a deadly web of addiction have proved impossible to eradicate.

In the earliest days of the opioid crisis, Rutland, a city of about 16,000 that had once been home to a thriving marble industry, was engulfed. It sat on a natural trade route: Amtrak’s Ethan Allen Express could reach New York’s Pennsylvania Station in just five and a half hours.

In Rutland, residents of multiunit rental houses were hosting out-of-town dealers who sold heroin for $30 a bag, a fivefold markup from the street in New York City. One 10-block area received three-quarters of all police calls in 2013 and 80 percent of the burglaries.

The Rutland police officers and a federal Drug Enforcement Administration agent who came to investigate Mr. Blanchard’s death sensed a rare opportunity. With a new body and the overdose not yet public, they wanted to find the source of the fatal heroin while evidence was fresh and undisturbed.

The trail led investigators to the onetime owner of a Manhattan wine bar with a secret life importing heroin; a Bronx man who perfected a potent mix of ingredients to create Flow; and a murderous drug crew that hawked it on New York’s streets and branched out to Rutland after finding it could charge more there.

And for one New York prosecutor, the investigation led to a place both surprising and familiar. Flow was ravaging not just the Bronx neighborhood the prosecutor was trying to make safer — it had become a plague in the Vermont city where she had been born.

The Bronx, 2014

Shawn Crowley occupied an office on the seventh floor of the U.S. attorney’s headquarters in Lower Manhattan. The carpet was shabby, the battered wooden desk was filled with the detritus of previous prosecutors and the blinds didn’t come down all the way. The view was of a jail.

She had worked hard to be there.

In Vermont, she had grown up on a former dairy farm at the end of a dirt road atop a hill in East Wallingford, a village of several hundred about 20 minutes south of Rutland. Her mother had worked as a veterinarian in the city.

Heroin wasn’t the community’s problem yet — poverty was. But her home was a haven. There were horses, a cow, chickens and a barn where neighbor children gathered to play basketball on a makeshift court. Ms. Crowley skied on Killington Mountain. In high school, she was often the only girl on the freestyle team.

After graduating from Northwestern University, she had returned for two years to Vermont, coaching skiing and working with her father, who sold medical supplies. Then, in 2008, Ms. Crowley left for Manhattan: law school at Columbia University, a stint in private practice and a clerkship for a judge. In September 2014, she became a federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York and was assigned to its general crimes unit, where rookie prosecutors, “general crimesters,” begin their careers.

Her family and friends back home had told her about how heroin was seeping into Rutland. She had seen Facebook posts by people who had spotted users in the Walmart parking lot.

In New York, Ms. Crowley had handled many drug cases and knew all too well how heroin and violence had devastated parts of the Bronx. In 2014, a surge of shootings hit the borough’s northernmost neighborhoods. By mid-May, one news report said, there were eight killings in one police precinct, compared with a single homicide to that point the year before.

Ms. Crowley learned which crews controlled which blocks, where the stash houses were and who was beefing with whom.

When she was 31, about six months into that education, her supervisor handed her a case that had been kicking around for a couple of years. It would be her first trial.

The defendant was Ruben Pizarro, a young Bronx man known as Chulo, who was a ruthless dealer of crack and cocaine. He had been arrested some 30 times but had avoided real jail time, in some cases because witnesses refused to talk.

Chulo and a companion were charged in a 2012 robbery of a livery cabdriver. The authorities said Chulo struck the driver in the head, then held a knife to his throat as he turned over $180. As the robbers fled, the other man spat on the taxi.

With Bronx prosecutors unable to get Chulo off the street, the police brought the robbery to the Southern District in 2013 hoping the feds would have more success.

The prosecution would not be easy. The DNA from the saliva on the taxi had led the police to the accomplice, who pleaded guilty. But the man had not agreed to testify, and although the driver had identified Chulo from a photo, there was no video of the robbery or witnesses. No knife had been recovered.

Ms. Crowley was eager to try her first case, but she fretted that there was little proof to present to the jury. Her supervisor asked if she thought Chulo was guilty.

He’s definitely guilty, Ms. Crowley replied. And so the trial went forward.

It lasted four days in August 2015. As the jurors filed in, Ms. Crowley noticed one smile at Chulo. The verdict was not guilty.

As Ms. Crowley left the courthouse, she saw Chulo taking selfies with a female friend.

Southern District prosecutors rarely lost trials, and Ms. Crowley’s colleagues stopped by to commiserate. That night, another supervisor emailed her. “Trust me,” she wrote, “there are more than a few prosecutors who would shy away from the tough case.” That Ms. Crowley gave it everything, the supervisor added, “is a testament to the kind of prosecutor you are, the only kind we want.”

Ms. Crowley told a detective: Next time you arrest this guy, call me.

Rutland, 2012

Heroin starts as opium poppies, for thousands of years cultivated in Asia or Latin America. The fluid that seeps from incisions in the plant’s unripe seedpods is scraped out, dried and formed into bricks or balls. Boiled with lime, morphine is extracted, then processed in a laboratory into heroin. It comes to America on airliners, hidden in cargo ships and slipped through border crossings.

Street dealers brand each fix with a rubber stamp. The empty glassine bags litter city streets. They are emblazoned with names like Sleep Walking, Power Hour, Hello Kitty.

Flow.

Ms. Parker and Mr. Blanchard had been regular heroin users, often two bags a day each. That August morning, after Mr. Blanchard came back from his job, he went on their recurrent hunt for drugs. He called a regular connection, a former nursing assistant who lived nearby. They met outside the Walmart where Mr. Blanchard, after cashing his paycheck, paid her $100 for four bags.

Back at the motel, Ms. Parker and Mr. Blanchard were excited to see the Flow stamp. This, they thought, was the good stuff.

They loaded their syringes and, as their daughter watched television, they shot up and nodded off. After Ms. Parker came to, she and the toddler spent the day grocery shopping, doing laundry and playing in the motel parking lot, so Mr. Blanchard could sleep.

Late that afternoon, Ms. Parker placed their child on Mr. Blanchard’s chest. It was a family game: The girl would crawl on her father until he awoke. “Oh, who’s on me?” he would say, and begin tickling her.

This time, he did not wake up.

Ms. Parker vomited and sobbed with their daughter in her arms — and she agreed to help the investigators from the Rutland police and the D.E.A. trace the deadly heroin to its source.

She directed them to a pale yellow house on Meadow Street where the former nursing assistant who had sold them the Flow lived on the second floor with her two young children. The woman gave up the name of her supplier, a 19-year-old man from New York. He had been ferrying Flow for the Bronx crew that operated on the block at Hughes Avenue and 178th Street in Tremont and wholesaled to dealers in Rutland.

A few days later, New York police officers spotted the man in the South Bronx after a report of gunshots. He tossed away a plastic bag containing 1,365 packets of Flow as he ran before he was arrested. But he wouldn’t help investigators in return for leniency. The Hughes Avenue crew was too dangerous to defy.

The Bronx, 2010

Vermont marble was ubiquitous in New York’s Gilded Age mansions and monuments. Now the commerce between the cities was not veined rock, but white powder.

In New York, heroin and the violence that accompanied it shadowed Tremont’s 32,000 residents. The Hughes Avenue crew sold Flow heroin brazenly, with a reputation for violence that was an essential element of its business.

The crew had announced itself with a killing.

In 2010, the two brothers who led the crew got into a beef with a man named Jerry Tide, a 26-year-old household mover and amateur boxer who had nothing to do with the drug trade. Mr. Tide had talked to the wrong woman inside Remy’s pool hall, but he didn’t back down. The confrontation escalated, with bottles flying down Jerome Avenue. A bottle hit one of the brothers, cutting his face.

Six months later, the brothers ran into Mr. Tide in the pool hall again. They got a gun from their stash house and waited. As Mr. Tide left Remy’s that night, the brothers confronted him, and one said, “Do you remember what you did to my face?”

Mr. Tide was shot more than a half-dozen times point-blank, and was left to die in the street.

Five years later, the Hughes Avenue crew was at war with Chulo, the dealer who had beaten the taxi robbery charge in August and was back on the street. The crew had the Flow franchise and its leaders didn’t want their business disrupted by a violent rival a few blocks away.

Chulo had set up a beachhead in an empty apartment in a five-story brick building on Arthur Avenue across from William W. Niles middle school. In the apartment, he cooked cocaine into crack. He kept a .357 magnum in the stove and slept with a nine-millimeter pistol.

Chulo competed with the Hughes Avenue crew for territory and customers. Their so-called pitchers even jockeyed to intercept the addicted as they left a drug-treatment center.

That Halloween, Chulo ordered one of his men to take a shot at a Hughes Avenue pitcher. The next day, several Hughes Avenue soldiers drove to Arthur Avenue and opened fire on Chulo and his associate in front of his building. They ran to the roof and the associate fired a volley down at the street.

Giulia Cox, the principal of Niles and the only person at the school that Sunday, was seated in front of a window in her second-floor office preparing for a staff development day. Frightened, she crouched under her desk and dialed 911. As she began to speak, loud bangs could be heard.

“There’re shots being fired in front of my school,” Ms. Cox told the operator in a steady voice.

Other callers reported hearing screaming in the streets and at least a dozen rounds ring out.

Ms. Cox hid in a windowless copy room for about 20 minutes. Returning to her office, she saw police officers outside, working in an area cordoned off with yellow crime scene tape. One officer was digging a bullet out of a tree trunk.

The Bronx, 2015

On the evening of Nov. 3, 2015, days after the firefight, Ms. Crowley, the young prosecutor, was on the couch in her apartment when the phone rang.

Are you Shawn? a police officer asked.

The officer said the police had arrested a man named Anthony Ramos — street name Roach — after he made a drug sale. At the 48th Precinct, officers found four small bags of crack hidden between his buttocks and $79 in his pocket.

Roach had told the police he was selling for Chulo, slinging crack and cocaine at Arthur Avenue and 180th Street. He was also buying cocaine for Chulo to sell.

Roach had been arrested several times, making him a good candidate to be flipped. Within two weeks Ms. Crowley was meeting with him and his lawyer at the Manhattan federal courthouse.

It soon became clear that Roach was playing a dangerous game: Some of the cocaine he was supplying to Chulo was coming from the rival Hughes Avenue crew, which, he said, also sold a particularly powerful brand of heroin: Flow.

The name meant nothing to Ms. Crowley. But after conversations with a team of colleagues and an F.B.I. special agent, John Reynolds, she realized Flow meant everything to them.

They had been working for months to take down the Hughes Avenue crew that was the source of the drug, infiltrating it using wiretaps and a high-level informant.

And it was then that Ms. Crowley learned that the investigation had begun with a single overdose at a motel hundreds of miles to the north. Flow, she realized, was not just the bane of the city where she lived — it was consuming Rutland, the place where she had spent so much time.

Ms. Crowley and her colleagues decided they would work together.

The Southern District’s investigation into the Hughes Avenue crew had begun in mid-2015 with the arrest of a Bronx man named Neil Lizardi.

Mr. Lizardi had a degree from Lehman College, and he had worked for nearly two decades with Verizon, earning as much as $100,000 a year. He had also owned a wine bar on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. But Mr. Lizardi had a less public profession: heroin supplier.

As he was being driven to the F.B.I.’s field office in Lower Manhattan, sitting in handcuffs in the back seat with Agent Reynolds, he asked: What can I do to help myself?

Soon, Mr. Lizardi was telling Agent Reynolds everything.

He said that he had been selling heroin to dealers in the United States for years after buying large quantities from Colombia, Mexico and the Dominican Republic.

One longtime customer was a middle-aged Bronx man named Ramon Cruz. Over half a decade, Mr. Lizardi had sold Mr. Cruz as much as 100 kilos for more than $6 million — with a street value of millions more. Mr. Cruz used a coffee grinder to cut the heroin with an unidentified substance Mr. Lizardi called “the secret ingredient.”

Mr. Cruz then packaged his product in glassine bags, folding and taping each one and stamping it “Flow.”

Mr. Lizardi said that since around 2010, Mr. Cruz had been selling Flow to the Hughes Avenue crew, which had a lucrative secondary market in Rutland. One customer had even died of an overdose there, Mr. Lizardi told Agent Reynolds, who would become a kind of confessor for the supplier.

Mr. Lizardi was released on bail and kept talking. He wore a wire and a camera, and in August 2015 the F.B.I. began recording his calls with Mr. Cruz. They were a window into the crew’s operations: the violence, the business plan, even the drudgery.

Mr. Cruz talked about the pool-hall killing of Mr. Tide, the amateur boxer whose death had helped to establish the crew. In another recording, he complained about working through the weekend to produce 4,000 bags of Flow, bagging until 11 p.m., folding the baggies until 4 a.m. “Boom: I showered. Boom: I fell into bed, and I got up at 10,” he said.

Mr. Lizardi once asked Mr. Cruz whether he had ever considered changing the Flow brand name. “Dude,” Mr. Cruz replied, “how am I going to change it? That’s what sells — those stamps.”

On Nov. 24, the violence between Chulo and the Hughes Avenue crew escalated. There was a killing, one caught on video.

Chulo and one of his associates had shot a Hughes Avenue pitcher outside a Tremont day care as parents were dropping off children. Chulo had chased the man through a parking lot, firing repeatedly. The man fell, struggled to stand and was punched to the ground. Chulo then shot him in the heart and fled.

Days later, Mr. Lizardi’s wiretap revealed a plan for the Hughes Avenue crew to gun down Chulo in retaliation.

It was time to make arrests. On Dec. 2, the police and F.B.I. picked up the Hughes Avenue crew’s street leader and Mr. Cruz, the middleman. In his apartment, they seized baggies, scales, grinders and strainers. There were thousands of dollars in cash, cutting agents like quinine and mannitol, packages of heroin, gold chains, watches and a gun. They took a rubber stamp with the word Flow.

A police manhunt did not turn up Chulo. Finally, on Jan. 12, 2016, a tip led the police to an abandoned building a few miles from Tremont.

Chulo, on the run for seven weeks since the parking lot shooting, was captured as he tried to escape from a second-story window.

Rutland, 2016

In March 2016, with the Hughes Avenue crew’s leaders and chief supplier locked up, Ms. Crowley and her colleagues piled into a white minivan in Lower Manhattan for a half-day drive to Rutland, with Agent Reynolds at the wheel. It would be the first of several trips to prepare for trials in New York.

The arrests of Roach, the Bronx street dealer, and Mr. Lizardi, the supplier at the pinnacle of the operation, had been revelatory for Ms. Crowley. She realized that what might have seemed like discrete episodes — Mr. Blanchard’s death at the Rodeway Inn, Chulo’s shootouts with the Hughes Avenue crew, the murder of Mr. Tide — were all part of a single economy of heroin that stretched from New York to New England.

The ride took the investigators and prosecutors north to Route 7 in Vermont, through the Green Mountains and into Rutland, where handsome New England homes lined the streets before giving way to a rundown section.

At a gas station, Agent Reynolds saw the telltale signs of heroin addiction: hollowed out, anxious, disheveled people, shells of their former selves. He had seen this again and again in the Bronx, where years before he had worked as a police officer.

Ms. Crowley showed her colleagues her high school and her favorite deli, and at night, they stayed at her childhood home outside of town; her parents were away.

They stopped by the Rodeway Inn where Mr. Blanchard had died, and they met with the D.E.A. agent, Tom Doud, whose investigation had tracked the fatal dose of Flow to New York.

He told them how dealers arrived in Rutland by car or Amtrak train. Ms. Crowley knew that train: She had taken it to Rutland for the holidays. For dealers, it was a short walk from the station to the neighborhood where heroin had made a troubled home.

In a building that housed a satellite F.B.I. office, Ms. Crowley and her colleagues met with Ms. Parker, Mr. Blanchard’s former partner.

Masking tape held Ms. Parker’s glasses together, and she paused for cigarette breaks as she spoke. Ms. Crowley sensed her deep shame and sorrow. She had gone through rehab, she had been allowed to raise her daughter, and she had a job. But Ms. Crowley worried that a setback could send her reeling.

Ms. Parker asked whether she had to take the stand at the trials in Manhattan. Ms. Crowley was firm: You’re doing this because you got clean. You’re doing this for your daughter.

Manhattan, 2017

Three Manhattan trials resulting from the Flow investigation stretched over nearly a year in 2017 and 2018.

More than a dozen defendants had already or would soon plead guilty to federal charges in Vermont and New York. Among them was Mr. Cruz, then 52, who had packaged Mr. Lizardi’s raw product into Flow. He pleaded guilty in Manhattan to a drug conspiracy ending in Mr. Blanchard’s overdose death and got 25 years in prison.

Some who took plea deals agreed to testify for the prosecution, including Roach and Mr. Lizardi.

At one trial, one of the brothers who had run the Hughes Avenue crew, Jose Santiago-Ortiz, was convicted of murdering Mr. Tide outside Remy’s pool hall.

The trial was lightly attended and barely covered by the news media. But Mr. Tide’s mother, Marlene Louis, was there every day.

“My son was a good man, a humble man,” Ms. Louis told the judge when he let her speak before laying down his punishment.

She turned to the defendant. “You happy you kill him that morning?” Ms. Louis said. “Now you have to be happy to get your sentence.”

Mr. Santiago-Ortiz was sentenced to three consecutive life terms.

In another trial, Chulo was found guilty of murdering the Hughes Avenue pitcher whom he had shot outside the day care center. A mother who had been walking her young son there testified that Chulo, as he hurried from the scene, had caught her eye and smiled.

Ms. Crowley told the jury in her closing argument that the man’s death was “the culmination of a brutal drug war.” She said Chulo “armed himself for that war with guns, and he used those guns to commit shootings and to murder.”

Chulo, addressing the judge at his sentencing, said that his rivals had shot at him often. “I’ve been going through this with these guys for many years,” he said.

“I’m not trying to make no excuses,” he continued. “I just want to be treated fairly.”

“If I was doing something wrong, I apologize.”

The man who had avoided prison for so long was sentenced to 75 years.

In the third trial, the street boss of the Hughes Avenue crew was ultimately convicted of narcotics conspiracy and a gun charge for which she was sentenced to 10 years. The first witness was Ms. Parker, who had been given immunity from prosecution in return for testifying. A prosecutor asked if she was still using drugs.

“No,” Ms. Parker said.

How long had she been clean?

“Since the day David died,” Ms. Parker said. She added: “I love my daughter. She already lost one parent to it. She didn’t need a legacy of losing both to it.”

Rutland, the Bronx, 2025

Heroin, however, does not allow uncomplicated endings.

In the years since testifying in New York, Ms. Parker, who is now 47, has been arrested repeatedly for shoplifting offenses in Vermont and missed nearly a dozen court dates. In December, she was charged with attempted theft of nearly $400 worth of groceries five days after Christmas. Surveillance video footage showed her filling a supermarket cart with eggs, cheese, grapes and steaks and then heading for the parking lot without paying, the police said.

Then, one evening last month, she was arrested in Rutland after the state police said they found cocaine and drug paraphernalia in a car in which she was a passenger. The police recommended to prosecutors that she face a felony possession charge. Efforts to find her through her lawyer and several acquaintances yielded nothing.

One person who had long suspected Ms. Parker was using again was Shirley LaPine, Mr. Blanchard’s mother. While Ms. Parker was in rehab, Ms. LaPine cared for the couple’s child — her granddaughter — before the playful toddler was returned to Ms. Parker.

Ms. LaPine has not seen her granddaughter, now a teenager, in years.

Recently, in a small first-floor apartment outside Rutland, Ms. LaPine opened a closet and pulled aside its jumbled contents — clothing, scrapbooks, a vacuum cleaner — to reveal a brown plastic box with a faded photograph of her son affixed to one side. It contained his ashes.

“I feel like he’s closer to me if I don’t bury him,” Ms. LaPine said.

The Flow case was a triumph for the investigators and prosecutors who had devoted years of their lives to it. Murders were solved, killers were punished and the Flow pipeline was disrupted.

In a broader sense, it was hard to know what the case had achieved. Ms. Crowley knew that operators like Mr. Lizardi had grown rich while workers and customers like Roach and Mr. Blanchard were doing time or dead.

Vermont’s annual fatal opioid overdoses, which reached 235 three years ago, dropped to 180 last year — still more than three times the number in 2012 when Mr. Blanchard died. The estimated number of people in Vermont receiving treatment for opioid addiction — 11,500 — has more than doubled since 2012, according to the State Health Department.

In the Bronx, local Health Department teams in Tremont and the nearby Crotona neighborhood removed more than 31,000 syringes found on the ground last year.

As for Ms. Crowley, she has moved on to a new chapter of her legal career, but the destruction opiates wrought in the Bronx and in Rutland is never far from her mind.

“I always felt like I’ve gone off and made this life and I’m trying to help the community that I live in now,” said Ms. Crowley, who, after six years as a prosecutor in Manhattan, became a partner at a private law firm there. “But what about the community that I came from?”

In Vermont, one loss was particularly personal. In 2015, a childhood friend of Ms. Crowley had been featured in a news article about how Rutland was trying to free itself from the heroin epidemic with a combination of law enforcement, social services, treatment and sheer determination. The friend said she had gotten help and hadn’t used in two years.

In 2021, she died of an overdose.

“You’re never really free of it,” Ms. Crowley said. “And that’s what’s so sad about Vermont. Vermont is never going to be free of it.”

Read by Benjamin Weiser

Susan C. Beachy contributed research. Audio produced by Sarah Diamond.

Benjamin Weiser is a Times reporter covering the federal courts and U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan, and the justice system more broadly.

The post How a Single Overdose Unraveled an Empire of Heroin appeared first on New York Times.