In the far-flung hamlet in southern Mexico where he grew up, Hugo Aguilar Ortiz’s boyhood job was to herd goats. Nearly everyone around him on the mist-shrouded slopes of Oaxaca persisted in speaking Tu’un Savi, known as the language of the rain, even centuries after the Spanish conquest.

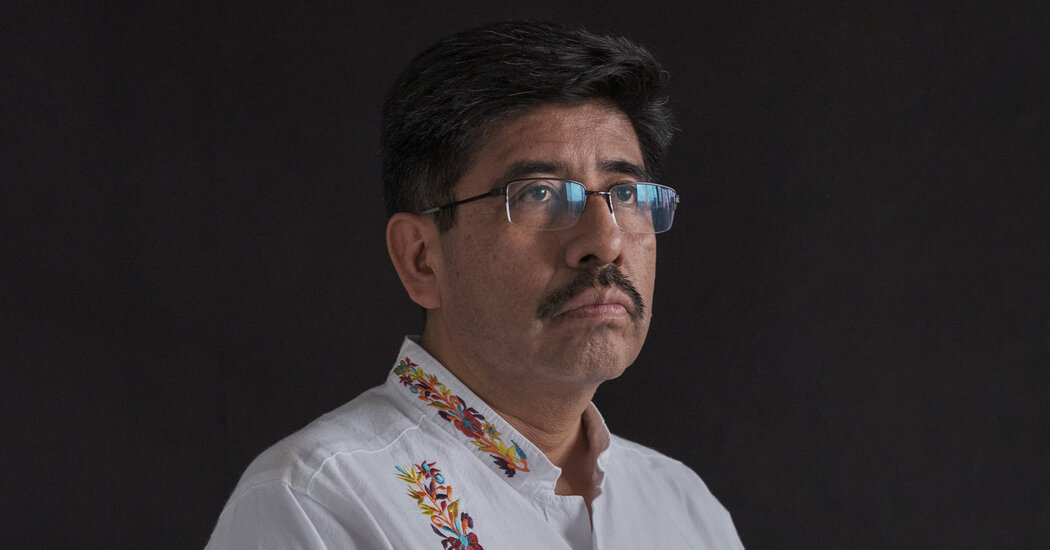

“I thought the world ended at the mountains,” said Mr. Aguilar Ortiz, now 52 and the newly elected chief justice of Mexico’s Supreme Court. “I never thought about becoming a lawyer.”

Dealing a jolt to Mexico’s legal establishment, he won his seat in the country’s first judicial elections, part of a sweeping redesign of the judiciary by the leftist governing party, Morena. It rewrote the Constitution to let voters directly elect thousands of judges around Mexico, ending the previous appointment-based system.

Feuding over the judicial overhaul has consumed Mexico for the past year. Critics say it erodes the last major check on the power of President Claudia Sheinbaum’s party, which already controls the executive branch, both houses of Congress and most statehouses across Mexico.

But Morena’s supporters contend that the changes were needed not only to root out the judicial system’s corruption and nepotism, but also to make judgeships attainable to those traditionally excluded from positions of power. Mr. Aguilar Ortiz’s metamorphosis from goatherd to chief justice bolsters such ambitions.

“Things can change now that we have Hugo there,” said Alejandro Marreros Lobato, a Nahua human rights activist, who drew on Mr. Aguilar Ortiz’s support in a legal battle against a Canadian open-pit mining project near his Nahua community. “It makes me feel that we can finally start talking about justice.”

In an interview, Mr. Aguilar Ortiz said he aimed to prioritize the rule of law and the needs of Indigenous peoples as chief justice, citing his own path to the Supreme Court. Both of his grandmothers in the village of San Agustín Tlacotepec spoke only Tu’un Savi (also called Mixtec). His father was a teacher; his mother tended the fields.

After leaving his village to attend law school, he said, he was a legal adviser to the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, the armed rebel movement that became a global phenomenon in 1994 after staging an uprising in southern Mexico demanding greater rights for Indigenous peoples. He said he helped transform the group’s concerns into concrete legal demands, though others involved with the Zapatistas at the time said his involvement was not substantial.

After his time with the guerrillas, Mr. Aguilar Ortiz practiced law with a focus on human rights. Then he joined the Oaxaca state government in 2011 as under secretary of Indigenous affairs, but resigned a few years later after hundreds of police officers brutally repressed a teachers’ demonstration in Oaxaca in which eight people were killed.

When Andrés Manuel López Obrador won the presidency in a landslide victory in 2018 with pledges to improve the lives of the poor and other neglected groups, Mr. Aguilar Ortiz seized on another opportunity. He joined a federal agency as general coordinator of Indigenous rights.

He has emerged as one of Mexico’s most visible Indigenous figures at a time when Indigenous Mexicans face myriad challenges.

While about 19 percent of Mexico’s population identified as Indigenous in the 2020 census, they are underrepresented in Congress, executive suites, the media and the courts. Speakers of Indigenous languages are dwindling. Poverty and threats from drug cartels are forcing many Indigenous people to migrate to Mexican cities or to the United States.

Underscoring how marginalized Indigenous peoples remain in Mexico, historians say that Mr. Aguilar Ortiz is thought to be only the second person publicly identifying as Indigenous to lead the Supreme Court in more than 160 years. The first was Benito Juárez, a Zapotec lawyer in the 19th century who become president and a national hero.

Juárez, whose statues now stand in plazas across Mexico, and Mr. Aguilar Ortiz share some similarities. Both hail from Oaxaca, though they belong to different Indigenous peoples. Both grew up in poverty in families eking a living out of the land. Both left their hometowns to study law in the state capital.

And like his predecessor, Mr. Aguilar Ortiz has become a polarizing figure. Some celebrate the new chief justice as a symbol of national pride who has fought to protect Indigenous rights. Others view him as a political creature, cozying up to power in ways that support Mexico’s governing party while neglecting Indigenous communities.

Some of the unease involves the outcome of the judicial elections. Candidates aligned with Morena now dominate the Supreme Court, a new tribunal with the power to fire judges and court circuits across the country. Turnout in the election was dismal. Only 13 percent of voters bothered to cast ballots.

Mr. Aguilar Ortiz rejected such criticism, insisting he will base his rulings on the law. Despite his work for Mr. López Obrador’s government, he said that he was not a member of Morena and that his election win reflected voters’ desire to democratize the judicial system, especially among those from Indigenous communities.

“Morena didn’t place me here, nor did the president, Congress or any other politician,” he said.

Still, his role in the federal government has raised concerns even among some of his admirers. Joaquín Galván, a lawyer from a Mixe community in Oaxaca, said he got to know Mr. Aguilar Ortiz as they tried to find a resolution to a violent clash over water access with a neighboring town.

Mr. Galván called the new chief justice “brilliant” on an intellectual level. But he said he wondered whether Mr. Aguilar Ortiz would return to the idealism of his youth or would keep to “what he’s been doing for years as a political and strategic operator of the federal government and Morena.”

Mr. Galván and other critics argue that Mr. Aguilar Ortiz was essentially running cover for the former president’s flagship infrastructure projects. Those included a 1,000-mile train line in the Yucatán Peninsula, and a network of railways, roads, and ports linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans that was promoted as an alternative to the Panama Canal.

Mexico’s government had a legal duty to conduct consultations with Indigenous communities affected by the projects. These consultations, which were Mr. Aguilar Ortiz’s brainchild, came under criticism from the United Nations and other groups who said they failed to clearly explain negative impacts or fully comply with international human rights standards.

“The president had already decided that these projects were going to be done so what options were left to those in charge of implementing the consultations?” said Francisco López Bárcenas, a Mixtec lawyer and researcher at the Colegio de San Luis in San Luis Potosi. “They ended up justifying the projects because that’s what they were asked to do.”

But others said it was precisely the work that Mr. Aguilar Ortiz did for the federal government that moved them to vote for him.

Crisóforo Valenzuela, a representative of the Yaqui town of Ráhum, in the state of Sonora, said Mr. Aguilar Ortiz helped develop a justice plan for the Yaqui people. The plan involved the return of more than 100,000 acres and an apology for the genocide and enslavement of thousands of Yaquis in the 19th century.

“He is a person who has the same ideals that we have,” Mr. Valenzuela said. “He left us in awe.”

Simon Romero is a Times correspondent covering Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean. He is based in Mexico City.

Emiliano Rodríguez Mega is a reporter and researcher for The Times based in Mexico City, covering Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

The post He Was a Goatherd as a Boy. Now He’ll Lead Mexico’s Top Court. appeared first on New York Times.