“Squid Game,” the candy-colored South Korean series about a deadly competition, premiered on Netflix in 2021 and almost immediately became an international sensation. Hwang Dong-hyuk, who wrote and directed the series, could hardly believe it.

“Literally, I pinched myself,” he said, gripping the skin of his cheek. “It was very surreal to me.”

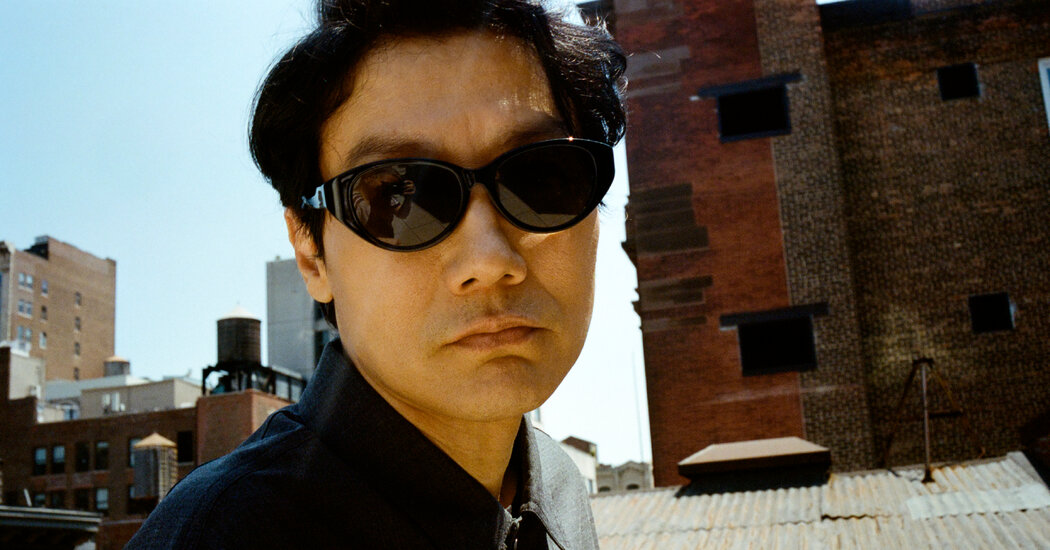

Hwang was speaking — sometimes in English, sometimes through an interpreter — earlier this month in the breakfast room of a luxury hotel in midtown Manhattan. The series was conceived in far shabbier locations.

In 2009, having earned a master’s in film at the University of Southern California, he found himself back in South Korea, broke and demoralized. Spending his days huddled in cafes, reading grisly comic books and sliding deeper into debt, he began to dream up a story about a competition, based on popular children’s games, in which players would either solve all their money woes or die. No one would finance that nascent feature until nearly a decade later, when Netflix came calling.

In its first season, “Squid Game” became the streamer’s most popular series ever, spawning think pieces, spinoffs, memes, bobblehead dolls. You could buy a “Squid Game” tracksuit, emblazoned with 456, the player number of the show’s protagonist, Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae). You could participate in less lethal recreations of the games, with on-site snack bars and a gift shop. A capitalist satire had become a capitalist triumph.

“It’s still surreal,” Hwang admitted.

Initially, he had been reluctant to continue the series. The shoot for Season 1 was overwhelming, to the point that he delayed basic health care and had to have multiple teeth extracted after production was over. But encouraged by Netflix, Hwang agreed to make two more seasons, which were shot in a block. Season 2 premiered on Dec. 26, quickly becoming Netflix’s most watched premiere, though critical response was more muted. Netflix will release all six episodes of the third and final season on June 27.

Speaking a few weeks before the debut, Hwang, playful in a pink and blue dress shirt, wouldn’t spoil the ending, but he did suggest that it conveyed his hope for humanity. If you have seen the series, which has a prodigious body count, this seems unlikely. But Hwang appeared to mean it.

Over an Americano, Hwang discussed art, commerce and why he’s happy to be done with “Squid Game.” These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Did you ever think you would be world famous?

I dreamed of being famous. The reason I came to U.S.C. was that I wanted to be a filmmaker in Hollywood, but I had to come back to Korea to make my debut film. I gave up my dream of Hollywood. I was too far away for too long. Then all of a sudden it happened: “Squid Game” brought me back to Hollywood. When I stopped dreaming, the dream came true.

What’s your best guess about why the show became so popular?

We touched something in the zeitgeist through “Squid Game.” The sense of urgency, the sense of crisis that weighs heavily on people’s daily lives, it allows anyone to easily relate to Gi-hun. That I tackled the issues of society’s limitless competition through children’s games, that contrast appealed to a lot people. We have all played these games. It tugs at your nostalgia.

After Season 1, you were reluctant to make more episodes. Why?

I wrote and directed and produced that whole season. It was torture. I mean, I lost eight teeth. So while I was shooting it, I kept telling myself and my producer, “This is it. I’m never going to do a TV series again. Not this way.”

Why work this way? There are writers’ rooms. There are other directors in the world.

Korea’s situation is totally different. There are no writers’ rooms in Korea. And as a filmmaker, I always worked by myself. So if I wanted to do it, I had to do the whole thing on my own.

What was different about writing and shooting Seasons 2 and 3?

It wasn’t easy. I killed all those beloved characters from Season 1, so I had to create new characters for Seasons 2 and 3. I thought it would be nice to include people who are related to each other. So there’s Gi-hun and Gi-hun’s best friend, a mother and son, an ex-boyfriend and his pregnant ex-girlfriend. These relationships that are very intimate. The hosts of the games did that on purpose for their greater entertainment value.

You’re like the hosts!

Yes, I am. I’m the mastermind.

Throughout, how realistic did you want the violence to be?

I wanted to portray what social failure means through the concept of death, because it’s social death that I’m talking about. So it was more of an analogy. But there are parts that have to be realistic for the sake of the story. So I do understand how it can feel very violent or brutal.

And how much are we meant to care about the characters? If we don’t care, we stop watching, but if we care too much the deaths are unbearable.

Honestly, I wasn’t aware of maintaining that balance. I personally think that the more you relate to the characters, the better. Because that’s where the entertainment comes from: being able to feel those strong human emotions along with the characters. But I find myself to be a bit of a prankster. I like to joke when it’s the most serious. So even though it’s not my intention to create distance from the characters, I have a cartoonish way of giving comic relief.

I understand “Squid Game” as a satire of capitalism — of its competitive pressures, its dehumanizing effects. How do you feel about the show becoming a marketing sensation?

I didn’t make “Squid Game” as propaganda. But through these stories, I want to raise issues about the fact that in late capitalism, we are failing to look after those who become the losers of the game. I don’t want to be radically against what Netflix is doing in terms of the merchandising and the experiences. Netflix, after it makes all the money it can, maybe it can use it for some good.

As for the viewers, I’m happy that they’re enjoying themselves. But I hope that after they watch the show, they will also take the time to think again about current issues. If they do none of that and only enjoy the goods and experiences, that could be a problem. But as long as it entails food for thought, I’m good with that.

A character in Season 3 gives birth. What does it mean to introduce a baby into this world?

We are all born with that innocence, but most of us, we turn for the worse. Things change as we live. The world changes us. A part of me wants to return to that innocence, that purity. So the baby you see in Season 3 is a symbol of how if we fail to put an end to the way the world is — our unstopped desire and our loss of humanity — there is no future for us. The baby symbolizes innocence. If we fail to protect it, then there’s no hope for humanity.

When Gi-hun goes back in Season 2, he wants to destroy the games. Do you believe in the power of individuals to effect change?

Gi-hun in Season 2 is like a Don Quixote. Don Quixote fights against all odds; he fails. Capitalism, it’s become too solid, too hard. A single individual like that, he’s bound to fail. A lot of the viewers were almost laughing at Gi-hun, mocking him for his foolishness. It made me sad. They point at him, thinking he’s a fool. That’s how much people don’t believe in change. We’re no longer living in an era where one person can come and change the world. But what can change the world now is self-awakening, self-realization. A change can happen if each individual awakens.

Are you hopeful about humanity?

If you watch the finale of Season 3, you’ll discover my answer. I am trying not to lose hope. The world forces us to become more sarcastic, more cynical. But like Gi-hun, I am trying my absolute best to stick to my conscience and maintain hope for humanity.

So success hasn’t corrupted you?

Not yet. I’m still living the same way. I still drive the same 10-year-old car.

Are you happy to be done with “Squid Game”?

Yeah, I’m very tired. I haven’t had a deep sleep for a long time. I want to take a rest. Then I want to do feature films. I have an idea for my next feature.

Is it as violent as “Squid Game”?

Yes.

Alexis Soloski has written for The Times since 2006. As a culture reporter, she covers television, theater, movies, podcasts and new media.

The post The Real Winner of ‘Squid Game’ Is Hwang Dong-hyuk appeared first on New York Times.