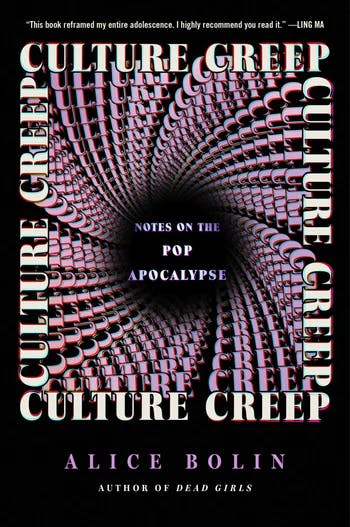

The year 2025 has produced a proliferation of essay collections by millennial women taking stock of the frenetic moment in which they came of age. Before Alice Bolin’s survey of early-aughts nostalgia, Culture Creep: Notes on the Pop Apocalypse, there was Colette Shade’s Y2K: How the 2000s Became Everything and the podcaster Kate Kennedy’s One in a Millennial: On Friendship, Feelings, Fangirls, and Fitting In, both published in January. Shortly after, Sophie Gilbert released a book with an inverse title and similar content, Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves. Naming all the artifacts covered by these books would produce a list as long and pink as a roll of Hubba Bubba, but a few of the fascinations they share include glitter, paparazzi, reality TV, Hiltons of the Paris or Perez varieties, AOL chat rooms, multilevel marketing, and, last but certainly not least, diet culture. Two of them feature comparisons to Jia Tolentino in their catalog copy, and another cites her collection Trick Mirror. Like Tolentino, these writers approach pop culture and consumer goods as ciphers for the contradictions of late capitalism, rather than trivialities. (Sweetgreen salads too can be a sign of the times.) Taken together, the urgency with which these authors reconsider their cultural upbringing—from the anticlimax of the millennium bug to the fragile, egotistic form of third-wave feminism that persists today—presents as a collective attempt to understand why we can’t seem to grow out of this political awkward phase. Naturally, the answer can be found in the candy-colored detritus of adolescence.

“This one’s got to start in my bedroom,” begins one essay in Bolin’s Culture Creep, about the now-defunct teen magazines that had their glory days from 1998 to 2002. The origins of contemporary influencer culture can be traced back to publications like Twist, CosmoGirl, Tiger Beat, and Seventeen, which featured trend pieces, personality quizzes, and reader-generated content and were heavily marketed to young women. Bolin describes her teenage self, curled up in pajamas on an inflatable chair, surrounded by well-worn issues of these mags. Such details, and “the cloud-printed pillowcases from the Delia’s catalog,” characterize girlhood as a soft and impressionable space. Case in point, Bolin occasionally writes in the argot of these magazines, chiming in with parentheticals like “LOL” and “not to brag.” Here, as in the rest of Culture Creep, she readily admits to being influenced by the glossy images of the early aughts, even divulging that she spent a significant amount of time making inspiration boards on Pinterest in the name of research for the book. Bolin admits to other “corrupting activities,” such as consuming true crime and chick lit, with some shame, while still acknowledging their inspiration.

Across seven expansive essays on everything from the NXIVM cult to Animal Crossing, Culture Creep explores how the rise of the internet transformed pop culture into a compulsive and corrupting force that stagnates social progress as it accumulates. Bolin argues that our collective nostalgia for the 2000s obscures its more noxious elements, making us susceptible to pernicious forces like misogyny and consumerism. She characterizes nostalgia in similar terms to her childhood bedroom: “comforting” and “soft-focused,” it renders us uncritical and foolish as teenage girls.

Insofar as she was once a teenage girl herself, Bolin comes across as an uneasy critic, one whose argument tends to get gummed up with apology and disclosures of complicity, as if her appreciation of pop culture might undermine her authority. While at times digressive, Culture Creep is also a hypnotic read precisely because Bolin is a magpie writer who fixates on shiny objects and pursues her fascinations. In that sense, nostalgia serves as radar, as much as a distraction.

Technology offers endless opportunities for nostalgic escapism, from buying old issues of Twist off eBay to streaming media that was once available almost exclusively on discs. The greatest challenge to consuming content from childhood, it seems, is finding anything without overwhelmingly offensive portrayals of women or casually racist remarks (for examples of either, watch Entourage, which aged like Trix yogurt). Two television series Bolin can’t help returning to are Star Trek: The Next Generation and Sex and the City. They hold up for the modern viewer not for being free from faux pas, but because their interrogative structures tackle the same dilemmas we face in contemporary culture, such as the ethical quandaries presented by technological advancement or dating under rapidly shifting social norms. For instance, Bolin sees Carrie Bradshaw’s inability to help but wonder as a symptom of the dissonance she experiences as a privileged woman who nevertheless struggles under impossible standards. Today, people on the internet are using Bradshaw’s turn of phrase to reflect on the absurd conditions of our economy. “As everyone checks their 401k,” they ponder, “Was I ever 0 k?” and “In a recession you cut back on non essentials. I couldn’t help but wonder … was I one of his?”

Crucially, this formula is not intended to resolve questions but rather to avoid answering them. It allows users to skirt unfortunate realities in favor of life’s more animating mysteries—for Carrie, keeping her romantic delusions alive; for the rest of us, achieving something close to self-actualization. The irony is in the illusion of agency, as if we could consider questions that high up on the hierarchy of needs from a place of such precarity.

By revising the media from our past with reboots, we avoid reckoning with their content, therefore maintaining the status quo and staving off the future.

This mode of catharsis is similar to the nostalgic escapism that occurs when we rewatch shows from the millennium. Sex and the City and the Star Trek franchise both got reboots in the last few years, as did Gilmore Girls, another 2000s series. In Bolin’s view, this looping disrupts our ability to interrogate the through lines between the past and the present. By revising the media from our past with reboots, we avoid reckoning with their content, therefore maintaining the status quo and staving off the future. “It’s time to end the long twentieth century,” she proclaims, “a period of stagnation exemplified by how many of us would rather treat nostalgic entertainments as a sensory deprivation tank than face a future currently staring us down.” Until we do, the country will continue to oscillate between social progress and political revanchism. Bolin points out that Next Gen’s utopic vision of society—which promotes the fallacy that prosperity and egalitarianism are achieved through individual responsibility rather than social revolution, and in which hierarchies are both necessary and remain firmly in place—is rooted in the Third Way thinking of the 1990s. Of course, acknowledging this fact, rather than writing Next Generation off as a relic, might force us to admit that this rationale resulted in the working-class exodus from the Democratic Party and the electoral defeat that gave us Donald Trump twice over. And scrutinizing Sex and the City for its neoliberal flavor of feminism, instead of blindly appreciating its impossibly idyllic rendering of city life, could result in the uncomfortable realization that we are still operating under a model of postfeminism that substitutes consumer choice for bodily choice.

When Third Way/ve policies fail to deliver on their promise of self-actualization, techno-capitalism has conditioned us to believe that we’ll find satisfaction from the sheer act of consuming and staying productive. In “The Enumerated Woman,” Bolin explores how self-tracking apps like FitBit and MyFitnessPal have enabled the resurgence of the dangerous diet culture that has tormented millennial women since their youth. The rise of social media has added additional incentive to these rigorous beauty standards. “Women are better and more invested than men, by and large, at projecting a coherent personality on social media,” Bolin argues. We are more susceptible, for one, because those teen magazines—with their personality quizzes and parables of which women not to be (i.e., bald Britney Spears)—made us more accustomed to choosing from “a curated catalog of identities.” “There must be some drive in the human psyche,” she speculates, “that takes comfort in shrinking ourselves, simplifying ourselves, surrendering ourselves.” In that sense, the best comparison for social media in the Y2K curio shop might be Shrinky Dinks, the special canvas that transforms drawings into little plastic charms when baked in the oven. Platforms like Instagram use algorithms to push people to make their bodies smaller and preserve their image so it can be marketed, turning individuals into products. Essentially, like the polystyrene novelty of yore, we’re all cooked.

The final essay of the collection, “The Rabbit Hole,” is a near-50-page examination of the Playboy empire born out of Bolin’s self-conscious obsession with celebrity tell-all memoirs that eventually brought her to Down the Rabbit Hole by Holly Madison, the principal Playmate on E! Network’s series The Girls Next Door. The reality show, which ran from 2005 to 2010, followed the girlfriends of octogenarian founder Hugh Hefner through an incessant string of parties at the Playboy mansion. Bolin reckons with her penchant for these women, as well as with Spears and Paris Hilton, all of whom perpetuated and profited off the oppressive patriarchal ideals of thinness, whiteness, and wealth that she rejects. It’s her turn to wonder, à la Bradshaw, “Was I only indulging my secret postfeminist sympathies, childishly playing with the blond Barbies of the Y2K imagination?” The essay is something of a dismal inventory of the many Playmates who attempted self-empowerment by playing into the same system that exploited them. Bolin also horns in a brief history of how the women’s liberation movement approached porn and sex work, pointing out that concerns about feminism’s image marginalized working-class and trans women. She spends more time wrestling with whether it is worth writing about her frivolous obsessions at all, questioning whether she is only further promoting their brand. In that sense, the essay serves more as an exorcism of those obsessions than a dedicated examination of stigmatized labor. Taking a psychoanalytic turn in the last few pages, she writes, “I experience a kind of Freudian repression, where ambiguous memories of my past continue to recur, and I have no choice but to sublimate them into ironic affection” and “to have fun with them in the same way I did then, when I didn’t know any better.” Such indulgences are, in Bolin’s view, a distraction from more serious efforts to address our present discontents that risks reproducing past mistakes. Her conclusion would seem to downplay the intellectual substance of this very collection.

Bolin was on the nostalgia beat as early as 2015, when she wrote the “Teen Witch’s Guide to Staying Alive” for Vice, an online publication one could nevertheless mistake for yet another nostalgia artifact. Back then, girls were donning brown lipstick and ’90s fashion in a throwback to “a wealthier, sweeter, frumpier era, when fashion trends tended towards a joyful eclecticism that at times veered gently into the occult.” People were thinking we might soon have a female president, and no one had said a word about reviving low-rise jeans. Bolin noticed a cultural resurgence of witches—a rise of spell-casting on crushes, the downloading of moon-cycle apps, the embrace of domestic routine. Such compulsive activities could be understood as an attempt to legitimize “the restless avenues teenage anxiety takes, the rituals of vigilance and control children are prone to.” These days, Bolin is far less sympathetic to nostalgia and other girlish whims. To some extent, she is right to be skeptical. After all, attempting to make anything from the present precious has proven too often to be a trap for our best feminist intentions. (Take, for example, the regrettable branding of Kamala Harris as Brat—which symbolized the Democrats’ preference for projecting a bold aesthetic over offering a coherent policy platform. See too Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, which once graced the New York Times bestseller list, only to be replaced years later by books like Tolentino’s Trick Mirror, rejecting Sandberg’s corporate feminist philosophy.) In Culture Creep, nostalgia also serves as Bolin’s own ritual of vigilance; her inspection of erstwhile icons and aesthetics leads to insights on what lessons to learn from their mistakes. At times, her vigilance veers into seeming penitence.

The contradiction that frustrates Culture Creep is that it is both insistent on the political importance of pop culture and skeptical of the merits of actually writing about it.

The essays in this book are exhaustively researched, loaded with citations of academic articles and social theory, in addition to some truly fascinating insights from Animal Crossing fan forums. But it’s hard to shake the sense that Bolin included some of these secondary sources to compensate for a concern that Y2K artifacts and early-2000s media are not topics serious enough to constitute an essay collection. She anticipates her detractors before they can come for her, flagging her awareness of the limitations of “the classic think piece genre where a feminist writer reconsiders the sex symbols of their childhood,” in which her own writing could be categorized. Pages into her first book, 2018’s Dead Girls, Bolin apologizes for her title, which “in addition to embarrassingly taking part in a ubiquitous publishing trend by including the word girls, seems to evince a lurid and cutesy complicity in the very brutality it critiques.” Bolin’s insecurity as a critic appears to stem from self-consciousness about participating in the genre of female-authored criticism-cum-memoir. In a disclaimer for the very premise of Culture Creep, Bolin admits, “I know I am on shaky ground criticizing people for the lighthearted kitsch they are attached to from their childhood. I’m the one reading Britney Spears’s memoir instead of real books.” I wonder what books Bolin considers “real”? Would she count her own among them? The contradiction that frustrates Culture Creep is that it is both insistent on the political importance of pop culture and skeptical of the merits of actually writing about it.

In the final pages of “The Rabbit Hole,” Bolin drives her argument home with a somewhat overwrought metaphor: that nostalgia encourages us to chase the iconic Playboy bunny down a hole where progress turns upside down and indoctrination resembles freedom. However, without affection, why else would we pay attention to these symbols from our past? Without seeing upside down, how would we notice that not everything from our present is right-side up? Because I’m a member of that hyper-earnest Generation Z, I ultimately find this millennial’s metaphor endearing, so I’ll extend it with this reminder: Before Alice was charmed by a plush bunny—even before she threw herself off the ledge in a bid to prove her bravery to those back at home—she was a curious girl bored by her sister’s “real book,” to borrow Bolin’s phrasing. “What is the use of a book,” thought Alice, “without pictures or conversations?”

The post Why We Can’t Quit Our Y2K Obsessions appeared first on New Republic.