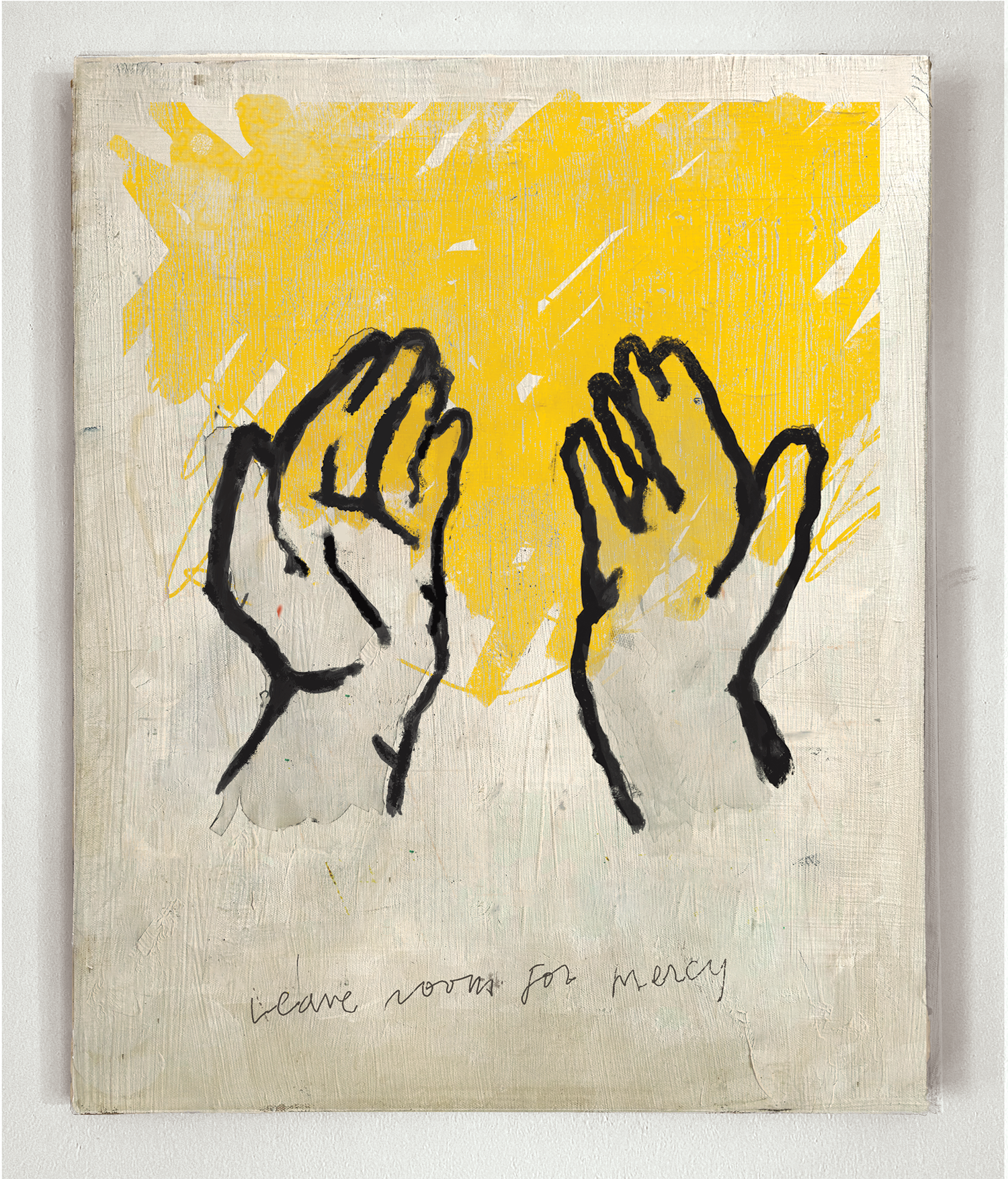

Art by Peter Mendelsund

Lately, I’ve been having dreams about my own execution. The nightmares mostly unfold in the same way: I am horrified to discover that I’ve committed a murder—the victim is never anyone I know but always has a face I’ve seen somewhere before. I cower in fear of detection, and wonder desperately if I should turn myself in to end the suspense. I am caught and convicted and sentenced to death. And then I’m inside an execution chamber like the ones I’ve seen many times, straining against the straps on a gurney, needles in both arms. I beg the executioner not to kill me. I tell him my children will be devastated—and somehow I know they’re watching from behind a window that looks like a mirror. I feel the burn of poison in my veins. After that comes emptiness.

Maybe everyone dreams of dying, even if not in quite this way. I once had nightmares about being a victim of crime, but after I began witnessing executions, I came to imagine myself on some subconscious plane as the perpetrator instead. This is perhaps a result of overidentification with the men I’ve watched die—and my understanding of the Christian religion, in which we’re all convicted sinners. I’m particularly interested in forgiveness and mercy, some of my faith’s most stringent dictates. If those forms of compassion are possible for murderers, then they’re possible for everyone.

These questions, combined with a murder that tore into my own family, inspired me, several years ago, to volunteer to witness an execution—one of 13 carried out at the federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana, during the final six months of Donald Trump’s first term. Most of the 23 states that still have an active death penalty allow a certain number of journalists to witness executions, as does the federal government. I sent an application to the appropriate federal office and, somewhat to my surprise, it was approved.

I had been trying to compose my thoughts about the death penalty for a while, distilling them into scraps and stubs of writing, but the only certainty I had going into the Indiana death chamber in December 2020 was the simple sense that it’s generally wrong to kill people, even bad people. What I witnessed on this occasion and the ones that came after has not changed my conviction that capital punishment must end. But in sometimes-unexpected ways, it has changed my understanding of why.

Capital punishment operates according to an emotional logic. Vengeance is elemental. Injustice cries out for redress. Murder is the most horrifying of crimes, and it seems only fitting to pair it with the most horrifying of punishments. All of this made sense to me when I was growing up in Texas, and so I wondered as I approached Terre Haute if some primal part of me would feel satisfaction: Recompense had been made.

The case of Alfred Bourgeois was the kind that advocates like to cite as justification for the death penalty. Bourgeois was a deeply unsympathetic figure—convicted in 2004 of the torture and murder of his toddler daughter, Ja’karenn Gunter, at the naval air station in Corpus Christi, Texas. Prosecutors said he had bashed the girl’s head against the inside of his truck after a prolonged period of abuse and neglect. The case was federal because the murder had been committed on a military base, and now the government was about to execute Bourgeois by lethal injection.

In my memory, everything about that night is green: the neat turf surrounding the penitentiary’s media center, glistening in the rain. The paint on the window frames inside the witness room. The cat eyes of Alfred Bourgeois himself. I was green, too: nervous in my seat in front of the windows that gave onto the execution chamber, sweat beading along my hairline as I breathed hot air against my face behind a pandemic-era mask. Static crackled when Bourgeois spoke his last words into a microphone that had been lowered over him. He protested his innocence, a claim his elder daughter has posthumously pursued with limited success.

And then the prison authorities started the injection. I didn’t expect Bourgeois to thrash on the gurney as he died, but he did. Lethal injection is advertised as easy. His death was not.

Killing Bourgeois was ostensibly about justice, or at least about vengeance. But as for any visceral sense of satisfaction, I felt none: Outside in the rain afterward, I threw up on the concrete. I found the spectacle as unnatural and disturbing as the murder itself had been.

I published an article about the experience, hoping, perhaps naively, that a straightforward account might encourage some people, somewhere, to pause for a moment and think about capital punishment. For the same reason, I also decided to try to serve as a witness on future occasions. I drew a grid on the chalkboard wall of my kitchen, with room for names and dates, so that I could keep track of death-penalty cases and scheduled executions as I learned of them.

I knew this meant I was effectively siding with killers, even if only on a single issue—whether they should be put to death. Morally, that made me nervous. I wanted to be on the exact right side of things: opposed to capital punishment for principled reasons involving the dignity of human life, but at the same time opposed to defending murderers in any way that might seem to downplay the seriousness of their crimes. It felt like a precarious position.

The next execution I observed was the result of another particularly heinous murder, this one in Mississippi. In 2009, Kim Cox, the estranged wife of a man named David Neal Cox, reported her husband to authorities for allegedly molesting her preteen daughter, Lindsey. Cox was taken into custody and faced charges of sexual battery and child abuse. Nine months later, he was released on bond. He found Kim and Lindsey at Kim’s sister’s trailer, where he took mother and daughter hostage. During an approximately eight-hour standoff with police, Cox shot Kim twice with a .40-caliber handgun. As she lay dying, he sexually assaulted Lindsey. Kim died before a SWAT team stormed the trailer and rescued her daughter. Cox pleaded guilty to all charges.

In September 2012, a Mississippi jury sentenced him to death. By 2018, Cox had begun to send letters to the Mississippi Supreme Court, asking that his lawyers be fired. He also wanted to waive further appeals: “I seek to be executed as I do here this day stand on MS Death row a guilty man worthy of death.” He said he deserved to die and passionately testified to his depravity, writing to the court, “If I had my perfect way & will about it, Id ever so gladly dig my dead sarkastic wife up of in whom I very happily & premeditatedly slaughtered on 5-14-2010 & with eager pleasure kill the fat heathern hore agan.” He saw himself as divided between two “skins,” one that sought “life & relief” and one that sought “death & relief, still.” In 2021, the death-seeking skin prevailed in the courts.

I volunteered to serve as a witness at Cox’s execution, traveling to the Mississippi State Penitentiary, known as Parchman Farm, in the low plains of the Delta. It was fall, but the season hadn’t yet touched the Deep South; there were still sleepless crickets in the evenings, and grand trees in summer dress. Prison officials directed witnesses into white vans, which took us along back roads to the execution chamber.

Cox uttered his last words, declaring in a short speech that he “was a good man, at one time.” In the moment, I didn’t know what to make of that statement, and truthfully I still don’t. Did he mean to say that he was irredeemable—that the path from good to evil ran only one way? Or did he mean the opposite? And which would be the stranger thing to say in his position? In the dim witness room, I transcribed his words. As for the execution, this time I was prepared. It didn’t turn my stomach when Cox’s face subtly changed color on the gurney, from pale to flushed, as the poison ravaged his body.

Afterward, Burl Cain, the commissioner of the Mississippi Department of Corrections, held a press conference. Cain emphasized that the process had been smooth, in part owing to his own relationship with Cox, which he characterized as congenial. Cox, in his final words, had thanked Cain for his kindness. Cain said he had comforted Cox in the chamber by telling him about angels carrying his soul to heaven. A reporter asked him if he believed that Cox was truly Christian. Cain quoted Matthew: “Judge not lest you be judged.”

Of course, capital punishment as an institution relies on judgment at every level: judgment about guilt, about fairness, about proportion, about pain and cruelty, about the possibility of redemption. Judgment about how to carry out a death sentence and how to behave as one does so. And then there is the judgment that must be directed at oneself and one’s community—the distant, sometimes-forgotten participants. In all of this, I see the arc of my own evolving comprehension.

In 1764, the Italian philosopher Cesare Beccaria published his essay “On Crimes and Punishments,” one of the first sustained arguments for abolition of the death penalty, which at the time was meted out as a punishment not only for murder but for crimes such as manslaughter, arson, robbery, burglary, sodomy, bestiality, forgery, and witchcraft. Beccaria reasoned that governments have no authority to violate the rights of their citizens by taking their life and that the death penalty was a less effective deterrent than imprisonment. Beccaria’s work was widely influential in the American colonies. By 1860, no northern state executed criminals for any crimes other than murder and treason.

Conditions in the South were different. In the mid-19th century, one could be executed in Louisiana for a variety of activities that might spread discontent among free or enslaved Black people: making a speech, displaying a sign, printing and distributing materials, even having a private conversation. “Throughout the South attempted rape was a capital crime, but only if the defendant was black and the victim white,” the historian Stuart Banner observes in his 2002 book, The Death Penalty. (There is no known record of a white rapist ever being hanged in the antebellum South.) Enslaved people were subject to a wide array of capital sentences and to exceedingly brutal forms of execution. American capital punishment took on an undeniably racist character.

Over time, the range of permissible execution methods narrowed. Public hangings largely fell out of favor in the 19th century, when the spectacle of executions came to be seen as not only coarse but coarsening. Firing squads, bloody and brutal, became exceedingly rare by the mid-20th century. Executions withdrew behind prison walls as electrocution came into fashion, beginning in the late 1800s. The electric chair was used thousands of times, despite its tendency to produce horrifying unintended outcomes, such as prisoners catching on fire. Execution by lethal gas became available in 1921, but gas, too, resulted in agonizing deaths.

In the late 1960s, the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund launched a nationwide campaign to challenge the death penalty not on strictly moral grounds but on a variety of legal ones, including the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Then, in 1972, the U.S. Supreme Court took up three death-penalty cases under the name Furman v. Georgia. Lawyers for William Henry Furman, who had been convicted of felony murder, argued that capital punishment as practiced in America—arbitrarily, and with intense racial bias—violated defendants’ Eighth Amendment protections because it imposed death sentences unfairly. The case split the Court in nine directions, with five justices issuing separate opinions in favor of the petitioner. Of those five, only two found capital punishment unconstitutional per se. The other three found that it was unconstitutional as practiced. One result of Furman was a brief moratorium on executions across the United States.

It was a hinge moment. As the death-penalty scholar Austin Sarat has noted, the “old abolitionism,” where opponents of the death penalty made their case in moral terms—mounting arguments about human worth and dignity—was giving way to a “new abolitionism,” where opponents instead focused their messaging on practical barriers to the just and humane application of capital punishment. These contemporary arguments involve factual observations about the death penalty as practiced—namely, that innocent people may be executed, that sentencing is arbitrary, that the handing-down of death sentences is heavily influenced by racism, and that the use of capital punishment is marked by horrific mishaps.

Executions resumed in 1977 after revisions to state laws. That same year, spurred by the grisly failures of electrocution, Oklahoma passed a bill permitting death by lethal injection, a form of execution that Ronald Reagan once analogized to having a veterinarian put an animal to sleep. Lethal injection was eventually adopted in every state that has the death penalty. It, too, has been the subject of much-publicized failures, as well as fierce litigation.

I learned firsthand about what could go wrong in the summer of 2022, when I received a call from a doctor who works with prisoners on Alabama’s death row. The doctor, Joel Zivot, told me that the state had likely botched the execution of a man named Joe Nathan James Jr.—sentenced to death for murdering Faith Hall, his ex-girlfriend, in 1994—and was keeping the matter secret. Witnesses to the execution reported that they had waited roughly three hours before they were permitted inside the facility, during which time James’s whereabouts were unknown, and that when the curtain to the execution chamber was finally opened, James appeared unconscious. The case drew my attention for another reason: Hall’s family, including her two daughters, had been opposed to the execution, saying that Hall believed in forgiveness and wouldn’t have wanted James put to death. I was struck by the advocacy of a victim’s family, which I wrongly assumed to have been very rare.

Time was short. James had been dead for a couple of days, and burial was imminent. The official autopsy report issued by the state’s Department of Forensic Sciences would not be available for months. With the help of James’s attorney and James’s brother Hakim, Zivot and I arranged for an independent pathologist to conduct a second autopsy to help clarify how James’s death had actually occurred.

The procedure took place at a funeral home in Birmingham on a seethingly hot day. Light shimmered above the pavement. Inside, box fans ventilated the small tiled room where James’s body lay on an examination table, draped in a shroud and a plastic sheet. When I arrived, his torso was already open, slit down the middle, with coils of intestines gathered alongside him. The top of his skull had been sawed off; his brain had been removed and sat in a clear bag. The pathologist lifted up the lungs to weigh them. I rounded the table to look at James’s inner arms.

Zivot had been onto something: Rather than cleanly inserting the two needles required for the injection, executioners appeared to have pierced James’s hands and arms all over in search of a usable vein. Bruises had bloomed near the puncture sites. Just below his bicep, there were slashes consistent with an attempted “cutdown,” when a blade is used to open the skin in order to access a vein. The number of slashes suggested multiple attempts. Mark Edgar, a pathologist at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, theorized that James had been thrashing on the gurney. (The Alabama Department of Corrections has denied that execution staff administered a cutdown.)

Something about the image—the blood, the nakedness, the evidence of pain—reminded me of giving birth, of the organic intensity that marks both ends of life.

I remembered Burl Cain, the corrections commissioner in Mississippi, saying he’d thought of the victims when David Neal Cox asked on the gurney if he would feel any pain. Cox, after all, had been ruthlessly indifferent to the pain of his victims. A great number of people come to the same conclusion—that to care about death-row prisoners is to slight the people they killed. But Cain made another observation: He couldn’t help the victim of this murder or her family; he could, however, help the prisoner in his custody. For that reason, he had comforted Cox. A similar desire to help, and the fact that the family of James’s victim had publicly forgiven her killer and campaigned to halt his execution, made me more comfortable with the sympathy I felt for him. I took pictures of his cuts and bruises and, in a small office at the mortuary, prayed for the repose of his soul.

Later, I wrote about James’s death, laying into Alabama state authorities for the evidently torturous execution and the attempt to cover it up. What had happened mattered. James was a human being, I meant to say, and, moreover, a member of society. It was around that time, the graphic encounter with James still fresh, that I started to dream of dying by lethal injection.

Joe Nathan James Jr., David Neal Cox, and Alfred Bourgeois were men I had never known personally. The experience of confronting their deaths was vivid, but also, on some level, remote. But that began to change.

To tell the full story of what had happened to James required reaching out to other men on Alabama’s death row. I had no idea what to expect, and was wary. The exchanges were initially terse, but in time became more familiar. I came to appreciate the personalities of the men, their relationships with one another, their complex interior worlds. Some were laconic and businesslike; others were friendly and conversational. I enjoyed talking with them—not just about the specific subject at hand but also about their life inside prison: candy bars from the commissary, visits from members of a local church, vigils for the dying.

The next prisoner scheduled to be executed in Alabama in 2022 was a man named Alan Eugene Miller, who on a summer day in 1999 had shot and killed two co-workers and a former supervisor. The other men on death row called him Big Miller on account of his 350-pound build. Charles Scott, a psychiatrist retained by Miller’s trial counsel, had concluded that Miller was delusional during his rampage. Another psychiatrist, this one for the prosecution, believed that Miller had suffered from a schizoid personality disorder at the time of the murders. Mental illness is extremely common among prisoners on death row, but the Supreme Court has never ruled that it disqualifies a person from capital punishment. Miller had a tendency to speak at length without much direction, to others as well as to himself. One acquaintance described him as “childlike.”

At first I mainly interacted with Miller through lawyers, friends, and family. Miller himself called me after the article about James was published. He was nervous but polite, with a high, reedy voice. His execution date had been set, and he wanted someone there to document what was going to happen to him. The Alabama Department of Corrections had not replied to requests I’d made about serving as a media witness to executions, and I did not entertain much hope that it ever would. But there was another way in. Each condemned prisoner is entitled to six “personal witnesses,” and Miller made me one of his.

On the night of September 22, 2022, I gathered with Miller’s family to count down the hours until midnight—after which Miller’s death warrant would legally expire. It was the first occasion I’d had to observe how a family experiences a loved one’s execution.

Miller’s family members were down-to-earth, genuine people. I had expected that they would be somber—and they were—but they also displayed a kind of gallows humor. Given the circumstances, any questions I had were ill-timed, but the family put me at ease and answered them. We were sharing something intimate: this preemptive mourning, this encounter with death.

But not long after we’d all moved into the witness chamber, a prison guard ushered us out, saying that the execution had been abruptly called off. As midnight approached, the state still wasn’t ready to proceed. Delays had been caused by Miller’s final appeals and also by technical failures in the chamber: Miller later said that he had been strapped down and pierced multiple times with needles as execution staff tried to access his veins. It would take Alabama time to secure another death warrant from the courts, and so for now, Miller would be spared.

Shortly afterward, I spoke with Kenneth Eugene Smith, the next man scheduled for execution in Alabama. One of Smith’s friends in prison had put us in touch. Right away, Smith was warm and courteous—surprisingly so, considering his situation. Pressure reveals character, and as Smith’s personality fell into relief, I concluded that whatever else he had been, he was also an amiable southern grandpa who reminded me of men I’d known in my childhood in Texas. Talking with him came easily. We connected over conversations about religion, our children, fantasy books and movies, his life on the inside. Eventually I came to think of him as a friend. His execution was scheduled for November.

Smith’s case was complicated. In 1988, Charles Sennett, an Alabama pastor, had resolved to have his wife, Elizabeth, murdered. He was involved in an affair and deeply in debt, so he took out a large insurance policy on his wife and began inquiring around town about paying for a hit. Smith agreed to take the job along with his friend John Forrest Parker. One March day, the two drove to the Sennetts’ home in the country, where they entered and found Elizabeth.

According to the coroner’s testimony, Elizabeth died of multiple stab wounds. The exact circumstances are hard to reconstruct. Smith would later insist that Parker had started battering Elizabeth, first with his fists, then with a cane—anything he could get his hands on. (Parker confessed to beating the minister’s wife, but claimed that he never stabbed her.) While Parker attacked Elizabeth, Smith ransacked the house and stole a VCR. The last time he laid eyes on her, he told police, Elizabeth was lying near the fireplace with a blanket over her body. Smith and Parker fled in Parker’s car.

Charles Sennett killed himself before he could be charged in his wife’s death. In 1989, Parker and Smith were convicted of capital murder. Smith appealed his death sentence, and in 1996, a jury handed down a sentence of life imprisonment instead. But a judge condemned Smith to death anyway—a maneuver known as judicial override, which would eventually be outlawed in Alabama. Existing sentences, however, were allowed to stand.

Parker had been executed in 2010, and Smith’s execution was now coming up. I offered to serve as a personal witness, and Smith accepted. On November 17, 2022, I spent the evening with one of Smith’s lawyers in his hotel room, relaying information as I learned it to Smith’s wife, Deanna “Dee” Smith, who was staying at another hotel nearby. Smith’s final appeal had been denied. All of us were waiting for the summons to the witness chamber. But the summons never came: The execution staff once again faced a midnight deadline and couldn’t beat the clock. The execution was called off. I relayed the news to Dee. That night, after Smith had been returned to his cell, I spoke with him and Dee on a conference call. Smith was in shock. He explained that he had been strapped down and ineffectually stuck with needles—much, I imagined, as Miller and apparently James had been. The execution staff had also jammed a long needle underneath his collarbone, looking for a subclavian vein. On the call, Dee recounted how Smith had dreamed earlier that morning of surviving his execution, marveling at what had occurred.

After Alabama failed to execute Smith in time, Kay Ivey, the governor, instituted a moratorium on executions for a few months so the state could review its procedures and protocols. (The results of the review were never made public.) When the moratorium was lifted and their second execution dates were scheduled, Smith and Miller again asked me to join them as they faced death, this time from suffocation by means of nitrogen hypoxia—according to experts, a form of killing never before used as a method of execution. Smith would die on January 25, 2024, and Miller on September 26.

I understand why people who favor the death penalty—more than 50 percent of all Americans—feel the way they do. Murder is an offense not just against a person and their family but against society itself, and all of us have a stake in how the state responds. Some people favor a lethal brand of justice, and I would have assumed, before murder entered my own life, that almost anyone directly affected by homicide would feel the same.

On a warm June afternoon in 2016, I was asleep in bed with our newborn daughter when my husband, Matt, came into the room to tell me that his 29-year-old sister, Heather, was dead. She had been stabbed to death so brutally that the first responders at the scene initially believed she had sustained a gunshot wound. The killer, a 25-year-old man named Javier Vazquez-Martinez, with whom she had been romantically involved, was apprehended after a police chase across Arlington, Texas. According to incident reports, he was intoxicated and in possession of drugs, an open container of hard liquor, and a knife. When interviewed by law enforcement, he denied ever assaulting Heather, but witnesses told police that Vazquez-Martinez had beaten her so severely in the past few weeks that she had been hospitalized. That’s the part that my father-in-law, Marty, often thinks about.

Marty is a retired forklift driver who still lives in Arlington, where Heather, Matt, and I all grew up. “Heather was a great daughter,” Marty told me. “She cared about everyone.” She was vivacious and beautiful, played basketball, and maxed out her library card every time she visited. Marty and Matt are quiet and reserved; Heather’s sociability made for a contrast. I remember meeting her: She was full of questions and seemed pleased that her shy younger brother had turned up with a girlfriend. Heather was murdered on Father’s Day, and Marty knew something was wrong when she didn’t call.

After the police notified him of her death, Marty was put in touch with a victims’ advocate, who would help shepherd him through the criminal-justice process. Eventually he was summoned to a meeting with a local district attorney in Fort Worth. Despite a lifetime in Texas, where capital punishment has broad support, Marty didn’t go into the meeting with a plan to campaign for the death penalty. “I know Heather wouldn’t have wanted it,” he explained to me. “I have Christian values and beliefs, though they wander from time to time.” He went on, “I just don’t think it’s the right thing to do. I don’t think it helps anybody.” Vazquez-Martinez was sentenced to 40 years in prison.

Like his father, my husband remains heartbroken by Heather’s death. It has been bittersweet watching her features blossom on our daughter’s face. Matt knows that the death penalty may serve an expressive purpose—signaling the depth of outrage and pain—but he ultimately holds to the same view of capital punishment that his father has in Heather’s case.

Families of murder victims routinely perform exceptional feats of mercy, if not forgiveness. “We’re pretty forgiving people, but I haven’t forgiven him,” Marty told me. Forgiveness is an emotional process that involves coming to see a wrongdoer as a moral equal again, and inviting them back into the place reserved in your heart for the rest of the world. To forgive someone who has harmed you is to forswear bitter feelings, which is to surrender a certain righteous power—the permission granted by society for retaliation. It is also therefore a kind of sacrifice. Only divinity can demand that of someone; no human being can demand it of another. And the Christian directive is especially exacting, requiring forgiveness for others in order to be forgiven oneself.

But mercy—to refrain from punishing a person to the maximum extent that a transgression might deserve—doesn’t demand half as much. It is hard to imagine forgiveness without mercy, but easy to imagine mercy without forgiveness. In his treatise On Clemency, addressed to the emperor he served, the philosopher Seneca describes mercy as “a restraining of the mind from vengeance when it is in its power to avenge itself”—in other words, a “gentleness shown by a powerful man in fixing the punishment of a weaker one.” The ruler who shows mercy is “sparing of the blood” of even the lowest of subjects simply because “he is a man.” Socially, mercy registers the value of human life. For the benefactor, it is a forge of moral character. For the recipient, it is a godsend.

The age of all-powerful sovereigns is mostly gone, but avenues for public acts of mercy remain. State governors, for instance, frequently opt to commute death sentences based on their evaluation of the circumstances. Legislators in many states have shown mercy to even the worst criminals by voting to end capital punishment. Mercy may be in some sense arbitrary, but so is capital punishment, and although mercy may produce unequal outcomes, unfairness in benefaction is better than the unfairness in harm that defines the American exercise of the death penalty. If one insists on complete and total fairness, then: no mercy, and no capital punishment.

Many people on death row are more worthy of love and respect than one might initially assume, and in such instances, mercy perhaps comes more easily. But choosing mercy is the moral path even in the hardest cases—even if you believe that some people deserve execution, even if you think you can judge the totality of someone’s character from their worst act, and even if you know for a fact that the person in question is guilty and unrepentant.

Seneca’s reasons for advising clemency are Stoic: It is better to restrain one’s impulses than to indulge them, especially when they involve destructive tendencies, such as wrath and cruelty. Self-control is a virtue, and it is possible to educate one’s desires so that they gradually change. To default to mercy is to impose limitations on one’s own power to retaliate, and to acknowledge our flawed nature. To a Christian, mercy derives from charity. And in the liminal space where families of murder victims are recruited into the judicial process—to either bless or condemn a prosecutor’s intentions—showing mercy is an especially heroic decision. To think this way is to understand that the moral dimension of capital punishment is not just about what we do to others. It’s also about what we do to ourselves.

Periodically, forgiveness and mercy meet under the right conditions to produce reconciliation. In the spring of 2001, James Edward Barber murdered 75-year-old Dorothy “Dottie” Epps during a drunken crack binge in Harvest, Alabama. He didn’t do it for money. He didn’t do it for any reason at all. His recollection of the incident was hazy, he testified, but he could recall being inside Epps’s house and picking up a hammer. For a time, Barber would later say, he was in “utter disbelief” and denial about what he had done. He fought in county jail, lashing out in shame and anger. He was living, by his own account, a “worthless life.”

But Barber slowly began to change. Isolated and restless, he began reading a Bible. And he was taken with it—fell in love with it; read it through once, then twice; and, eventually, signed up for correspondence courses. Barber became a friendly face on death row, much like Kenny Smith. “They were approachable open and willing to engage with anyone on almost any topic,” one death-row prisoner wrote to me over Alabama’s prison messaging app. “Jimmie always had a self deprecating joke.” According to his lawyer, Barber’s record inside prison was spotless. But there was something incomplete about his reform.

That changed in 2020, when he opened a letter from Sarah Gregory, Epps’s granddaughter, and found forgiveness inside. “I am tired Jimmy,” she wrote. “I am tired. I am tired of carrying this pain, hate, and rage in my heart. I can’t do it anymore. I have to do this and truly forgive you.” Barber was astonished—brought to his knees. He composed a letter of his own: “Sarah, sorry could never come close to what is in my heart & soul.” He went on: “I made a promise to myself in that nasty, dirty, evil county jail, I was never going to become ‘a convict.’ I made up my mind that when I left prison either on my feet or in a body bag I was going to be a better man than when I arrived.”

Gregory wrote back: “Receiving your letter was the final piece of freedom. The weight was lifted when I forgave you in my heart, but your response back brought me indescribable freedom and release.” The two began talking on the phone about life and God and Gregory’s son. Her forgiveness seemed to bind them together. “I love that girl more than I love anybody else in this world,” Barber told me.

As Barber’s time dwindled, Gregory realized she didn’t want to see him put to death. The day before his scheduled execution, Gregory told me that she was “losing a friend tomorrow.” She said, “I would’ve never thought I would’ve ever said that. He was a friend of mine, and I’m gonna miss him.”

On the night of July 21, 2023, I watched Barber die in Alabama’s death chamber. Afterward, his lawyers shared his final statement: “I made up my mind early on that mere words could not express my sorrow at what had occurred at my hands. And so I hoped that the way I lived my life would be a testimony to the family of Dorothy Epps and also my family, of the regret and shame I have for what I’ve done.” It wasn’t for him to say whether his efforts were successful. But they were enough for Gregory.

Barber was the first person executed after Alabama lifted its temporary moratorium and resumed lethal injections. I had corresponded with him on Alabama’s prison messaging app, and his sister-in-law had shown me a letter he’d written to her. He was joyful, kind, and encouraging—and grateful for so much, even in his position. I knew him well enough to feel certain that he was sincere in his remorse and repentance. The death penalty is, to some degree, indiscriminate: Both innocent and guilty people have been sentenced to death. But the death penalty is also morally indiscriminate in an additional way, in that it kills guilty people who may have become good people. By the time execution arrives, the offender may be a completely different person from the one who took a life. We can’t know the nature or potential of another’s soul.

Today, 27 states have abolished the death penalty or have halted executions by executive action. According to the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund, as of last summer, 2,213 people resided on America’s death rows, compared with 3,682 people in 2000. In each year during the past decade, fewer than 50 death sentences have been handed down by American courts. The Justice Department declared a moratorium on federal executions after Joe Biden took office, in 2021, and before leaving office, Biden commuted the death sentences of 37 of the 40 men awaiting execution in federal prisons. “It’s not an irreversible momentum,” Austin Sarat, the death-penalty scholar, told me, “but I think the momentum against the death penalty is pretty substantial.”

Yet for now, in the United States, the death penalty continues. Donald Trump has signed an executive order directing federal prosecutors to pursue the death penalty in all applicable cases. South Carolina recently carried out the nation’s first firing-squad execution in 15 years, and Louisiana resumed executions after a long hiatus—this time by nitrogen hypoxia. Perhaps worried about the continued practical feasibility of lethal injection, Oklahoma and Mississippi have also made execution by nitrogen hypoxia statutorily available within their borders. It would be quick and painless, proponents said. Just like going to sleep.

Kenny Smith, who had survived his first attempted execution, would be the first person ever to be put to death by means of nitrogen hypoxia. I arrived at the William C. Holman Correctional Facility a little after eight on the morning of January 24, 2024, the day before his rescheduled execution. I was accompanied by his wife, Dee, and his nieces and nephew. We passed through a metal detector and handed over our IDs, wallets, and keys to a guard stationed outside the visitation room.

Despite having gotten to know Smith for nearly a year and a half, I had never met him in person. I was surprised to see how tall and broad he was, an imposing presence softened by a graying beard and an avuncular demeanor. “C’mere, Little Bit,” he said, breaking into a smile as he rose from the table where he sat. “Gimme a hug.” The nickname was new; Smith had called me “ma’am” the first time we spoke and “hun” after that.

Smith and I sat down at the plastic-topped table where he huddled with his son Steven Tiggleman, his daughter-in-law Chandon Tiggleman, and his mother, Linda Smith. Dee leaned toward Smith across the table and murmured to him in quiet tones. The scene had the look of a last supper, everyone gathered close with melancholy faces, grieving in advance.

Hours passed. Dee and the others had brought in plastic baggies full of quarters to clink into the vending machines. No outside food was allowed in, so we drank Mountain Dew and Sunkist, and split bags of chips and honey buns and Skittles. Smith leaned against his mother. At one point, a prison worker came in and took pictures of all of us in a group. Smith and I stood together for a photo; he somehow managed a smile. A group of Mennonites came by to sing “Amazing Grace” on the other side of an interior wall. Conversation seemed to proceed in waves of fond reverie that peaked with laughter and then crashed into silence.

As night fell, I joined Smith’s family for dinner. We met at a casino a few minutes from the prison. The place was decked out for Mardi Gras—white artificial Christmas trees stuck with floral sprays of gold, green, and purple; masked harlequin puppets draped in multicolored beads. We sat together in the casino’s steak house. Rain began to fall as we ate, and continued into the next day. The prison’s gutters were flooded and gushing onto the stony pavement as we filed in to visit Smith one last time.

No more quarters were permitted inside, no more snacks and soda. Smith could potentially vomit inside the mask, something the state hoped to avoid by depriving him of food after 10 a.m. on the day he was to die. He’d eaten steak and eggs with hash browns from Waffle House for breakfast that morning, his last meal. Then he sat with us in cheaply upholstered metal chairs and talked.

Everyone took turns crying, holding on to one another for strength. Smith wept in his mother’s arms. Steven, a reserved and courteous man, spoke quietly with his father. Smith kissed Dee, massaged her shoulders, reassured her. She wore a shirt that said Never Alone, a gloss on Hebrews 13:5: “Keep your lives free from the love of money and be content with what you have, because God has said, ‘Never will I leave you; never will I forsake you.’ ” It was the same shirt she had worn to his first scheduled execution, back in 2022. Now it implied a shred of hope.

Smith led me to a couple of chairs side by side in a far corner of the visitation room and sat down with me. I was emotional, too; so much for steely journalistic resolve. Smith patted me on the back paternally and told me I could ask him anything I liked. So I asked him about his life and how he reflected on it. Smith wasn’t angry about his situation, or frustrated by the length of time he had spent alienated from society. He’d had a life before he went to prison, he told me. He had done a terrible thing, but he had also worked, had children, found love, and made friends. He had sustained those relationships behind bars, where many people wind up isolated and lonely. Smith had a vivid inner life.

Shortly after this conversation, prison officials struck me from Smith’s personal-witness list because I had brought pen and paper, something I had been told I wasn’t supposed to have, into the visitation room. Of course, this wasn’t strictly about pen and paper—it was about what I had already written and published, although the Alabama Department of Corrections denies this. I was summarily barred from Smith’s final moments and would be banned from serving as a personal witness in Alabama going forward. (And so I was unable to attend Alan Eugene Miller’s execution, by nitrogen hypoxia, in September.) But the accounts of others allowed me to follow events that night. Around 7 p.m., the U.S. Supreme Court rejected Smith’s final appeal, clearing the way for the state to carry out the sentence. The execution staff once again strapped Smith to a gurney, this time with an industrial respirator mask fixed to his face. As his family watched through the window between the death chamber and the witness room, the gas began to flow. Smith’s blood oxygen became depleted, his eyes rolled back into his head, and he began to convulse. For 22 minutes, Smith writhed and gasped, struggling for air, and then, finally, he died.

Later that night, at a press conference after the execution, Steven sought out the family of Smith’s victim, Elizabeth Sennett. He hugged them, and apologized—something he told me he had been waiting to do nearly his whole life, haunted by the burden of shame that connected their families. One of Sennett’s sons, Mike, hugged Steven back. When the reporters and TV crews were gone, Dee, Steven, and his brother, Michael, lingered with me on the patio of a Holiday Inn, smoking cigarettes and sharing shots of whiskey from a Dixie cup. Dee wept, swaying softly as she stood. Inside the hotel, she had clutched a green teddy bear Smith had given her, made from some of his prison-issued clothes, with a lock of his hair sewn inside. Now she looked at her phone as news alerts of her husband’s death popped up on the screen.

We stood and talked until midnight, when I said I had better get back to my hotel. I was feeling a little disoriented, fragments of the night’s conversations surfacing through the static in my head. I couldn’t make sense of the fact that Smith had survived once, only to be put to death in the end. Miracles are mercurial. As the time of execution approached, a reporter had asked Smith what his message to the public would be. “You know, brother, I’d say, ‘Leave room for mercy,’ ” he’d replied. “That just doesn’t exist in Alabama. Mercy really doesn’t exist in this country when it comes to difficult situations like mine.”

He was right about that. Now that he was gone, life after Smith had begun. I would clip the pictures of us together onto the refrigerator with a magnet, next to the school papers and crayon drawings. I would continue to seek opportunities to serve as a witness at executions, though now outside Alabama. I would resolve to greet the next person I met on death row with the kindness that Smith, Miller, Barber, and others had shown to me. And I would erase old names from the grid of capital cases on my kitchen chalkboard, adding new ones to take their place.

This article appears in the July 2025 print edition with the headline “Witness.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

The post Witness appeared first on The Atlantic.