When I read recently that the law firm Gibson Dunn had backed away from suing the Trump administration over its mass deportation policy for fear of becoming another of the president’s targets, I thought back to a dinner at a judicial conference in the late spring of 2009.

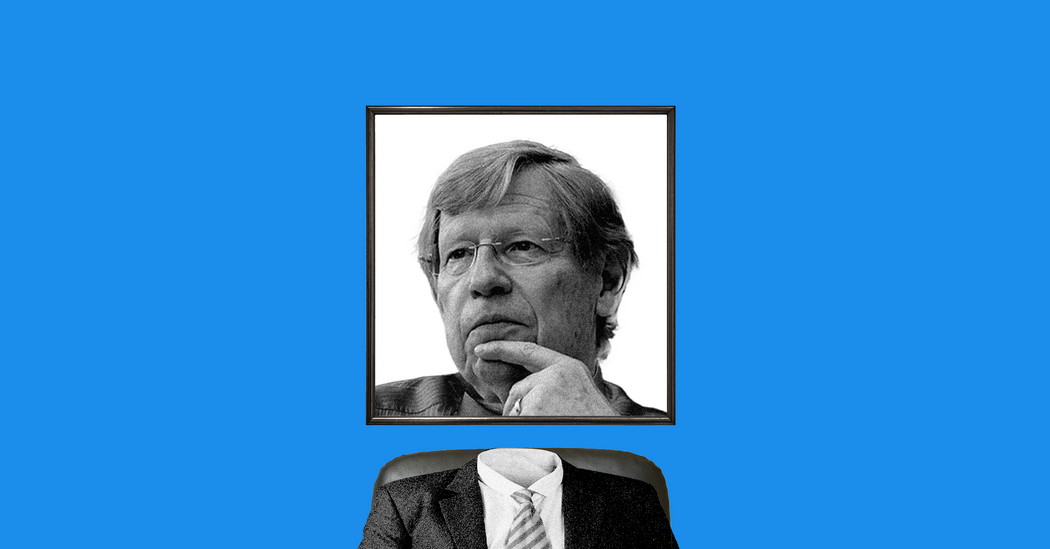

My dinner partner was Theodore Olson, the well-known Washington lawyer who represented George W. Bush in the decisive Supreme Court battle over Florida’s votes in the 2000 election. After serving as solicitor general in Mr. Bush’s first term, he returned to his law practice. His firm was Gibson Dunn.

Days before the dinner, Mr. Olson and his opponent in the 2000 election case, David Boies, announced that on behalf of two gay couples, they were suing the State of California over the ban on same-sex marriage imposed by Proposition 8, which the state’s voters approved the previous November.

Mr. Boies, a liberal, was a free agent, the founder of the law firm that bore his name. Mr. Olson was different, a founding member of the Federalist Society, a Republican insider who personified Big Law. The lawsuit drew fire from both left and right. L.G.B.T.Q. rights advocates were intensely distrustful of Mr. Olson’s motives and of the lawsuit’s chances, having spent years trying to cultivate political support for same-sex marriage while keeping the issue away from courts they viewed as hostile. An account of the lawsuit’s filing in The Times referred to the two lawyers as “limelight-grabbing but otherwise untested players in the bruising battle over Proposition 8.”

I was intrigued, and now here by chance was Mr. Olson, an elbow away. Why are you doing this, I asked him. What’s the story? His response removed any doubt I might have had about his sincerity or his commitment to his clients. He believed in marriage, he said. (I knew that his third wife, Barbara Olson, died in one of the hijacked planes on Sept. 11 and that he had recently married for a fourth time.) He had gay friends and saw no reason the law should prevent them from marrying the people they wanted to spend their lives with. Somebody would bring such a lawsuit, he observed, and it might as well be someone with his resources and lifetime of knowledge of how the federal courts worked. He believed he had a winning case.

His death last November at the age of 84, after suffering a stroke, meant that he didn’t live to see how quickly a Republican president’s extortion could reduce once-proud law firms to pitiable supplicants for the president’s grace. As the serial capitulations mounted, with firms promising to bestow millions of dollars’ worth of lawyers’ time on the president’s favorite causes in return for continued access to the federal government for themselves and their clients, I often thought of Mr. Olson and of how he might have responded. I know that my instinct that he would have fought back hard is presumptuous; no more than the rest of us, he could not have imagined what has unfolded, let alone formulated an anticipatory response to the unthinkable.

Gibson Dunn was not among the firms targeted by Mr. Trump with executive orders that would have seriously damaged their businesses had they not acquiesced to his demands. But Gibson Dunn, two months after suing the Trump administration to restore legal representation for unaccompanied immigrant children, did nonetheless stop providing help because it was fearful of the consequences.

Would Mr. Olson have demanded that the law firm where he spent his entire career, aside from interruptions for government service, not abandon its previous commitment to those children out of fear of giving offense? Of course, I don’t know, but I’d like to think he was savvy enough to know that those firms that decided to fight the president’s astonishing overreach were likely to win. One of them was Perkins Coie, even though many of the nation’s big law firms declined to sign a legal brief on its behalf.

The lawsuit that he and Mr. Boies filed was not the case that led to the Supreme Court decision establishing a nationwide right to same-sex marriage. That came later, in the Obergefell case, decided in 2015. The victory in the California case was limited to marriage in that state. After Federal District Judge Vaughn Walker declared Proposition 8 unconstitutional, Gov. Jerry Brown declined to appeal. The appeal was carried forward by the group that had proposed the marriage ban. The Supreme Court ruled in June 2013, in Hollingsworth v. Perry, that the group lacked standing, a decision that had the effect of making Judge Walker’s ruling the final word.

As random chance would have it, I was in Mr. Olson’s company again that summer when county clerks’ offices in California, responding to the Supreme Court’s Hollingsworth decision, began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. We were two of maybe a dozen people seated around a seminar table at Duke Law School. His cellphone rang, and he took the call. When he finished talking, he turned to the group and told us that it was one of his clients reporting that he had just been married. This tough embodiment of Big Law had tears in his eyes. Soon enough, so did many of the rest of us.

I don’t mean to suggest that the same-sex marriage case provided an epiphany that turned him into a liberal Democrat. Far from it. In the summer of 2017, he and I were speaking at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York, a place where a favorite evening activity is for people to gather their friends and even slight acquaintances to sit on a porch for a glass of wine and an evening’s conversation.

Mr. Olson and I and our spouses were guests at such a gathering, most of us journalists who had known him over the years. Mr. Trump had been in office for a few months, and it appeared to most of us that things were not going well. The Muslim ban, in particular, concerned us, and we gently poked at Mr. Olson to get him to express any doubts about the new president. He kept deflecting us, and we kept trying while being careful not to cross the line into rudeness. Finally, with a tired smile, he put his hands up in surrender. “Look, I’ll put it this way,” he said. “We got Gorsuch.”

Whatever the pros and cons of Mr. Trump’s first Supreme Court nominee, Neil Gorsuch, who took the seat that President Barack Obama intended a year earlier for Merrick Garland, it was a revealing moment. “But Gorsuch” was to become a mantra among Republicans who had their doubts about other aspects of the Trump agenda but not about his designs on the courts.

Mr. Olson’s comment was a deft conversation ender; there wasn’t much more to say. Yes, we all had Justice Gorsuch. And we also, for a time, had Ted Olson. I wish we still did. I think he would have something to tell us.

Linda Greenhouse, the recipient of a 1998 Pulitzer Prize, reported on the Supreme Court for The Times from 1978 to 2008 and was a contributing Opinion writer from 2009 to 2021.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.

The post What Would a Conservative Superlawyer Say About His Firm Bowing to Trump? appeared first on New York Times.