The first thing I did when my eight-year-old son was admitted for his life-or-death bone marrow transplant was check for furniture to barricade the door.

Movable objects sturdy enough to keep out any frantic staff should the worst-case scenario come to pass, should the need arise, to buy myself enough time to accompany him on his final journey.

The first thing he did when things went sideways was threaten to jump out the window.

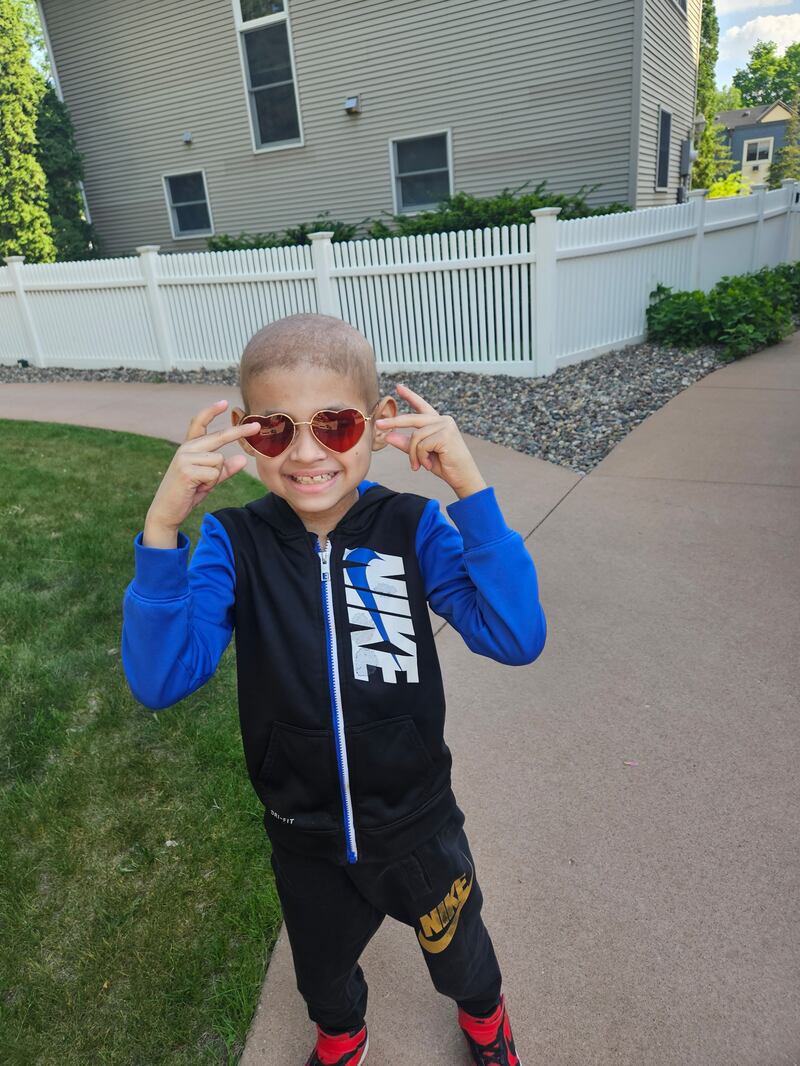

“Why did I even say that?!” he says now, nearly four months later, as he returns home to pick up where he left off with his childhood—albeit as a dramatically different child. Hardened, quick to anger and cry, cynical, keenly aware of death, and prematurely familiar with myriad forms of suffering.

After living among other kids battling terminal illnesses for the past several months, he wasn’t sure he could still relate to the third-grade classmates who’d waved goodbye to him in January with chants of “You’ve got this!”—and no certainty they’d ever see him again.

“I’m scared, they’re going to think I look weird now,” he groaned as we prepared to surprise those same classmates with my son’s homecoming this week. A commotion broke out the second he set foot in the school, audible gasps permeating the air and whispers of, “Is that who I think it is?” At least a few teachers fought back tears as celebratory cheers erupted from kids in the hallways: “Aedrik! Aedrik! Aedrik!”

Bald, slightly emaciated, and wearing an N95 mask, the guest of honor seemed uncomfortable with all the attention.

“Can we go home now?” he whispered.

The thing they don’t tell you about pediatric bone marrow transplants is that your child will be fundamentally broken; every perception a child has about their life being safe, stable, and predictable is obliterated. That trauma was the cost of saving my son’s life; if we had not gone through with the transplant, he may have already begun to lose his vision, or hearing, and he’d be on a fast track to death before his 10th birthday, courtesy of the rare and vicious disease adrenoleukodystrophy.

There’s an invisible turning point tucked away in the recovery process, and a question that has kept me up at night ever since I first saw my son’s eyes darken with a kind of rage that shouldn’t be possible for an eight-year-old while he was in the hospital: What will he do with the broken pieces?

I’m still haunted by the look in his eyes when, after throwing up mucus and blood for the umpteenth time as a result of scorched earth-level chemo, he confessed to me in a whisper: “I want everyone to suffer just like I am.”

Is he going to become a school shooter one day? is a thought I wish had not crossed my mind.

But this is where forces bigger than any one person entered the fray, and the unlikely hero of this story made his entrance: a pasty white clown with obnoxious red hair, a half-moon grin, and pinpoint eyes. You probably know him as Ronald McDonald, the one-time mascot of McDonald’s who in recent years has become more closely associated with the Ronald McDonald House Charities, a nonprofit that provides housing and support to families with kids battling life-threatening illnesses.

The garish red-and-yellow decor of Ronald McDonald belies the profound work that those working in his name do.

At a time when my son stood at a bleak crossroads on the edge of a cliff, gravitating toward anger and spite and holding a grudge against the rest of the world for his unfair misfortune, a bunch of strangers with absolutely nothing to gain from it climbed out onto the ledge and showed him what to do with the broken pieces.

They mopped up his vomit after he failed to keep his lunch down, his guts still ravaged by chemo. They threw him a birthday party in advance, complete with balloons and cake and an impromptu dance party to the B52’s Rock Lobster. They knew his name the second he arrived and never once got it wrong and they saw him when he felt unseen and helpless.

“They’re giving us this room and all of this food and asking for nothing in return just because they want to see you get better,” I told him on our first night in the Ronald McDonald House. “When life gets cruel, there are people who get compassionate.”

“What’s compassionate mean?” he asked.

“It means when it gets cold, they give away warmth to anyone who needs it.”

I could see a softening behind my son’s eyes throughout the weeks we stayed at the RMH, a melting of the broken pieces that had initially been so jagged and sharp. More than the meals and the place to lie our heads at night, the house gave us a kind of honorary family: other mothers and fathers facing unthinkable realities as they watched their kids fight for their lives; other kids trying to make sense of it all as everything they thought they knew about life went up in flames.

“Why is he in a wheelchair?” my son asked one day about another boy living in the house.

“I think he probably had complications from his bone marrow transplant,” I said. “A lot of kids have gone through the same things you have, and some of them haven’t been as lucky.”

It wasn’t long before he started remembering all the other children’s names—and asking each day how they were doing. He still does, even after we’ve returned home. Ahead of his 9th birthday, he wants to know if he can send some of his presents to a four-year-old boy named Gage, a fellow transplant patient he’d begun to view as a little brother.

“Is he allowed to play with Nerf guns?” he asks.

At a time when the most vulnerable feel especially hung out to dry and the country seems to run almost exclusively on grievance and outrage, the people and groups who’ll keep us all from going over the edge toil away quietly in the background. RMHC isn’t the only nonprofit churning out warmth when it gets cold. My son will get to have a normal birthday thanks to ALD Connect, a nonprofit set up for the unfortunate few who suffer from my son’s rare genetic disease that, put simply, catches them when they fall.

As we drove away this week from the hospital where he learned firsthand what it means to be broken, the same boy who just weeks earlier had wanted to see others “suffer” was staring out the window when he suddenly sat up and shouted at the bus driver: “Hey, stop!”

“What’s up?” I asked, slightly alarmed.

He pointed towards a nearby underpass, where an older man in ragged clothes that didn’t match the weather appeared to be living.

“That guy’s hungry and he needs help,” he said. “Let’s get him something to eat.”

The post Opinion: My Son May Have Been a School Shooter If Not for These Folks appeared first on The Daily Beast.