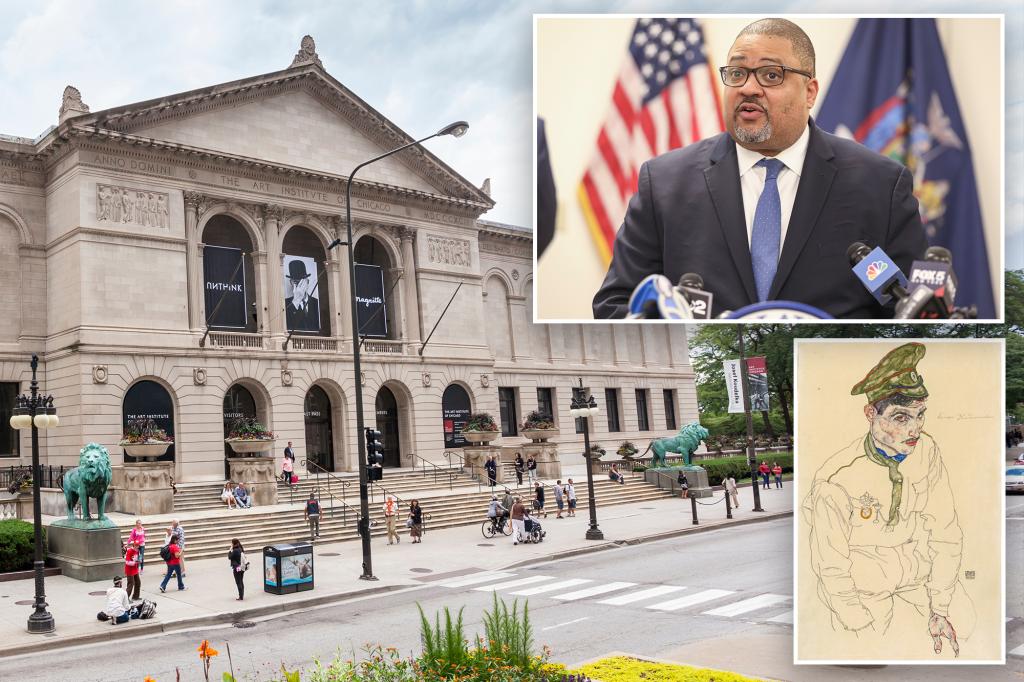

The Art Institute of Chicago has likely spent more than a million dollars trying to keep its claws on a Nazi-looted drawing in a Manhattan case shaping up to be “monumental” in the history of stolen works.

The school’s legal challenge to halt Manhattan prosecutors’ pursuit of the swiped art backfired last month, when a judge effectively ruled the district attorney’s office could hunt down such looted treasures if they ever pass through New York City — regardless of their current location.

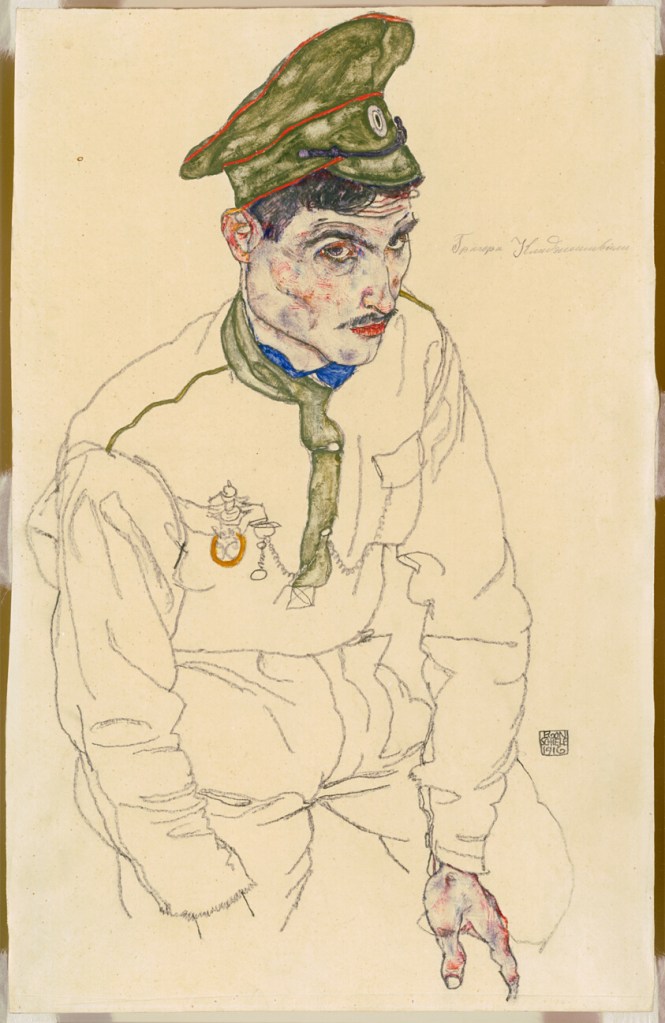

Manhattan Criminal Court Judge Althea Drysdale’s scathing decision against the art Institute came as the establishment has been fighting to keep a drawing by expressionist Egon Schiele titled “Russian War Prisoner” — likely spending well more in the legal battle than the work’s value.

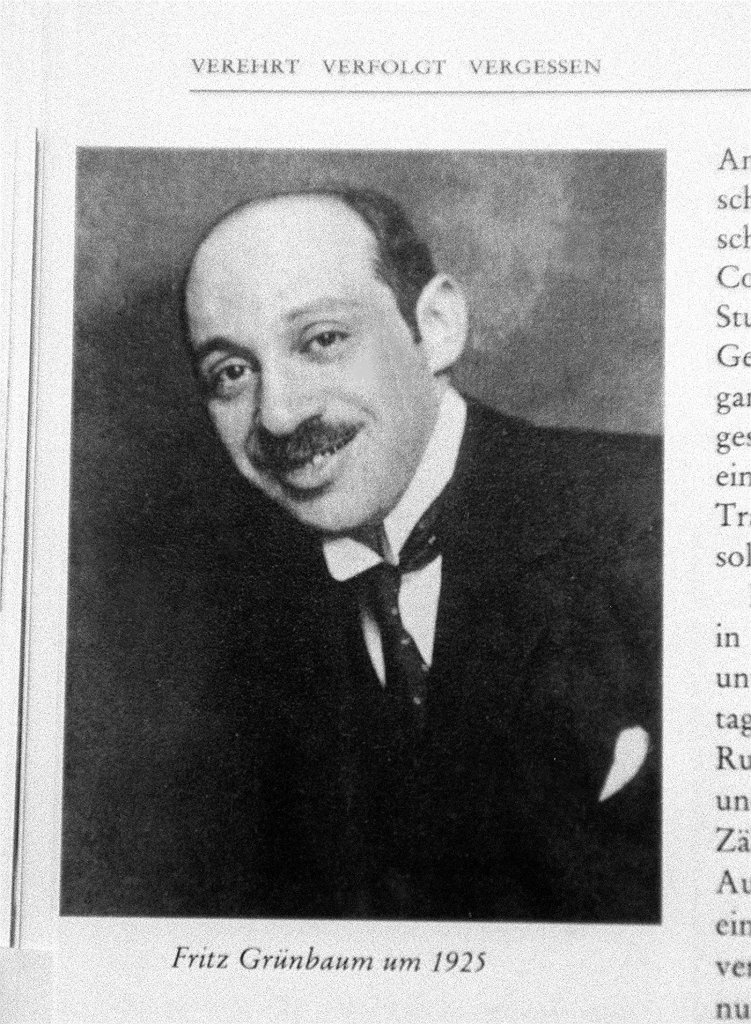

Her decision found that Nazi officials stole the work from the Viennese Jewish cabaret performer and art collector Fritz Grünbaum years before he was murdered in the Holocaust.

Grünbaum served as an inspiration for Joel Grey’s character in Hollywood’s Oscar-winning classic “Cabaret.”

The institute did not do its due diligence in determining the work’s history of ownership, the judge said.

“This Court cannot conclude that Respondent’s inquiries into the provenance of Russian War Prisoner were reasonable,” Drysdale wrote in her decision.

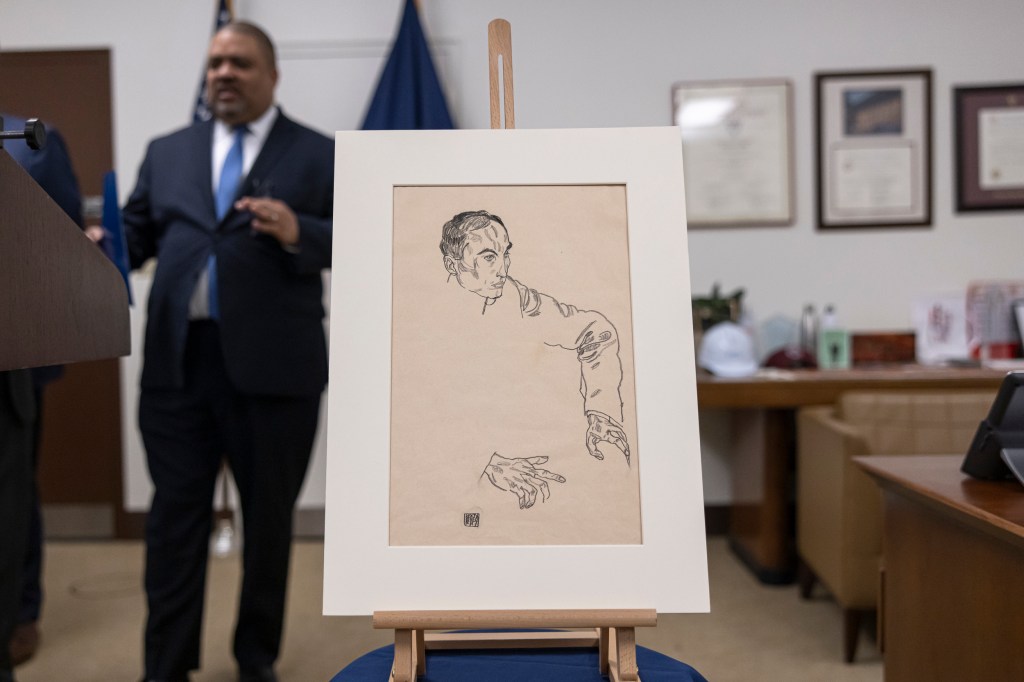

But critically, the ruling also found that Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg has jurisdiction to recover the art from Chicago because the work was purchased and displayed by a Manhattan gallery in 1956.

The DA’s office has not traditionally had to go this far in the courts to retrieve such a work.

Raymond Dowd, a lawyer and stolen-art expert who is working to return the stolen Grünbaum collection to the collector’s descendants, called the judge’s decision “extraordinary.

“[Drysdale’s] decision is monumental for the world because it says if it passes through New York City, the court will retain jurisdiction, no matter where it goes,” Dowd told The Post.

“There’s billions [of dollars] in Nazi-looted art hidden away,” Dowd said. “All those people sitting on that stuff are not going to be sleeping as well since Drysdale’s decision.”

While most institutions holding Nazi-looted work — including 12 other Schiele pieces once owned by Grünbaum — have willingly returned the art, the Chicago museum brought the biggest legal challenge yet to Manhattan prosecutors’ art hunt.

Experts say the Windy City art house easily blew more than the value of the Schiele drawing, estimated by the DA’s office to be $1.25 million, in its challenge.

“The Art Institute fought tooth and nail for well over two years,” Dowd said. “That’s a massive thing to do, an enormous financial investment. They wanted to cut off their jurisdiction. They wanted the DA to stick to New York.”

The work is being seized in place as the museum appeals the decision, the DA’s office said, adding it is “pleased” with the ruling.

Drysdale’s decision is already “the talk of the town,” said art lawyer and former prosecutor Georges Lederman to The Post.

In addition to expanding the DA’s jurisdiction, the court ruled that ownership questions, typically a civil matter, can be brought in criminal court when “there is evidence of theft,” Lederman said.

“I think this is a warning to museums and to collectors to dig deeper,” said lawyer Leila Amineddoleh, who also teaches art law.

But even in cases where “the ethics could not be more clear,” Amineddoleh said she worries about the practicalities of such rulings.

“We are putting today’s standards on prior acquisitions,” Amineddoleh said. “These involve really complicated factual inquiries for scenarios that took place decades ago with very little paper [record].”

But Lederman said, “If I were an institution, a museum, I’d be very concerned at this point in time.”

Bragg’s office has recovered 12 out of the 76 Schiele artworks once owned by Grünbaum, an outspoken and unafraid critic of Adolf Hitler.

Drysdale’s ruling traces the history of “Russian War Prisoner” from when Grünbaum lent the drawing for exhibits in 1925 and 1928 to his arrest and the seizure of his collection by Nazis in 1938.

Grünbaum was then sent to Dachau Concentration Camp, where he was murdered three years later.

While the dealer who sold the work to the Institute in the 1960s claimed that Grünbaum’s sister-in-law sold the Schiele drawing after the war, Drysdale states in her ruling that no record supports that claim.

That dealer, who also claimed Nazi’s never seized Grünbaum’s collection, was later revealed to be a “prominent dealer in Nazi-looted art,” Drysdale wrote.

“Despite these vibrant red flags, it appears as though the Art Institute of Chicago did nothing further to corroborate the account of a man whose credibility had directly been called into question on this very issue,” the judge said in her decision.

The art institute told The Post it is “disappointed with the ruling.”

“There is significant evidence that demonstrates this work was not looted, and previous courts have found that evidence to be credible,” a rep said.

The post ‘Monumental’ NYC ruling on Nazi-looted art tied to inspiration for Joel Grey character in ‘Cabaret’ appeared first on New York Post.