In early March, the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service released its annual Best Places to Work in the Federal Government rankings, based on a survey of over one million civil servants across 75 agencies. Good news! Over two-thirds of the respondents to the Office of Personnel Management’s Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey, or FEVS, administered in the summer of 2024, reported feeling “engaged and satisfied” with their jobs in the federal government—up 1 point from the year before. The Environmental Protection Agency and the National Institutes of Health were among those topping the list of popular employers; the Social Security Administration and USAID came in among the lowest. But no matter where in the rankings you start, the act of reading through the survey responses in the report produces the same effect: the eerie feeling of gazing at a snapshot taken just before a tsunami swept through.

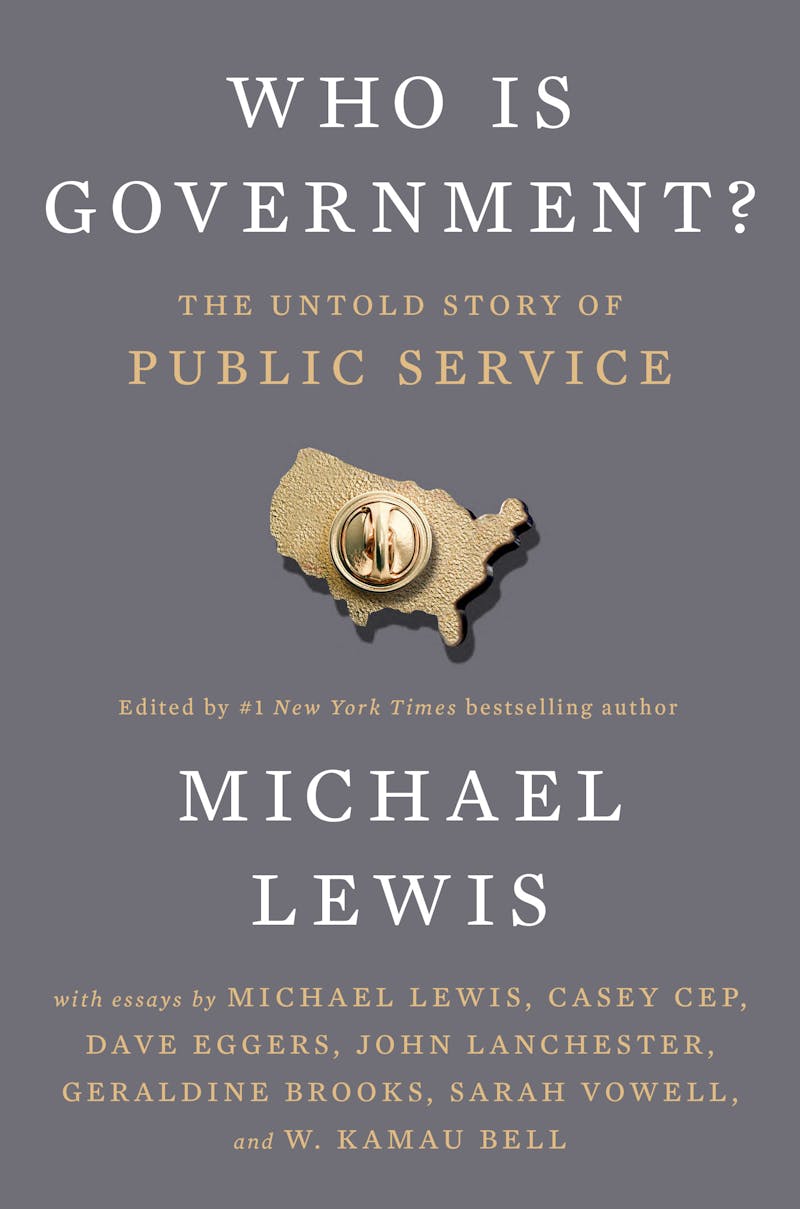

Reading the essay collection Who Is Government? The Untold Story of Public Service inspires something of that same haunting dissonance. Edited by long-form megastar journalist Michael Lewis, the book draws together seven portraits of heroic individual federal bureaucrats—along with one essay about a particularly heroic statistic, the Consumer Price Index—that first ran as a series in The Washington Post. Two of the pieces are Lewis’s, while the remaining six come from a roster of non-wonky, literary-leaning essayists: Geraldine Brooks, W. Kamau Bell, Dave Eggers, John Lanchester, Casey Cep, and Sarah Vowell. These are good writers, and the book is a fun read. Indeed, the fun is what’s strange. The contributions vary in quality as narrative and analysis, but what unites them is a deliberately light, human interest-y, ingratiatingly accessible tone—“wouldja look at these geeky do-gooders go?” That tone is the source of the dissonance. As substance, the book is timely in an extraordinarily urgent way; as vibe, it’s a disconcerting fit for that very topicality. The plucky, unheralded bureaucrats get their day in the sun in this book, their song finally sung at the exact moment that their work and the institutional scaffold supporting it fall victim to a mad paroxysm of destruction. Cue the power ballad: Don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone.

As deliberately light-touch as Lewis and Co. are with explicit argumentation, the essays in Who Is Government? do ultimately make the implicit case for bureaucracy—the core rationale for why we use government to perform certain tasks, and why lawmakers in that government would want to grant significant autonomy to unelected agents to carry them out. The writers’ shared instinct for character observation and portraiture, moreover, helps to elucidate a distinct ethos and personality type common in the civil service. It’s a culture that belies the image of a rogue deep state that animates Donald Trump’s demolition squad, whether in its vanguardist iteration under the Office of Management and Budget Director Russell Vought and his Project 2025, or in the edgelord tech-right anarchism suffusing Elon Musk’s DOGE. But it also stands unmistakably at odds with those wreckers’ own vision of work and collective purpose.

As it happens, the Partnership for Public Service gets credit for leading Lewis to the subject of the book’s first profile—a quietly intense engineer named Chris Mark, who spent multiple decades solving the problem of collapsing roofs in coal mines. Mark was nominated for an annual award the partnership gives out for extraordinary achievement in the federal civil service. Having written a bestselling book on the first Trump administration’s mismanagement of the executive branch, The Fifth Risk, Lewis has made a habit of reading through the partnership’s nominees each year. It’s a way to remind himself “how many weird problems the United States government deals with at any one time.” Coal mine roof collapses turn out to be just such a problem—centuries-spanning, chronic, and extraordinarily deadly. In Lewis’s hands, Mark’s lifelong engagement with the issue across multiple agencies, and its resonance with his engineer father’s scholarly preoccupation with the structural functions of Gothic cathedrals, become a fascinating story of governance as puzzle-solving and public commitment.

Lewis has gone through a shaky few years of late, marred by a strangely blinkered biography of Sam Bankman-Fried and some even more strangely dismissive public comments about Michael Oher, the disillusioned subject of his 2006 book, The Blind Side. But he’s a star for a reason. For the piece that concludes the book, a portrait of a Food and Drug Administration bureaucrat designing a website and app to help doctors find drug treatments for rare deadly diseases, he executes a seven-page opener that’s a masterpiece of distilled pointillistic narrative. With just a few strokes of detail and a handful of perfectly chosen quotes, Lewis gives us a world: a broken marriage between two indomitable personalities, the family they’ve built in spite of it, and a sci-fi-horrific brain disease robbing their five-year-old daughter of her personality and her future with terrifying speed. The bureaucrat in the story, Heather Stone, gets equally rich coloring, even as this case of government heroism involves a twist laden with troubling irony: sheer happenstance, rather than the underfunded and underutilized tool she’d designed inside the government, is what enabled Stone to help the family and save the girl.

If Lewis is throwing fastballs, his collaborators vary their pitches. Eggers mixes wonder and drollery in his fun account of visiting with the uber-earnest geniuses (and one charming absent-minded professor type) at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, or JPL. Bell interviews his own goddaughter about her entry-level job as a paralegal in the Department of Justice’s antitrust division. Vowell does her argument-via-tart-historical-digression thing in profiling the National Archives official tasked with building out the agency’s public online services.

There’s also variance in just how wince-inducing the essays read given the context of current events. Brooks, a journalist and novelist, profiles a Renaissance man bureaucrat named Jarod Koopman, jiujitsu instructor-cum-criminal investigator for the IRS. In fiction, she notes, “it would be considered malpractice to make up Jarod Koopman. You just do not give your protagonist a set of attributes that includes black belts, vintage trucks, sommelier certificates, tattooed biceps, a wholesome, all-American rural family and a deeply consequential yet uncelebrated and under-remunerated career in global cybercrime.” She details the painstaking work it took for Koopman and his team to unmask the identity of Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht and build the case that sent him to prison. (Trump pardoned Ulbricht, who then attended the president’s March address to Congress as Kentucky Representative Thomas Massie’s guest of honor.) She does the same for Koopman’s investigation into the cryptocurrency exchange Binance, whose fraudulent practices produced a $4.3 billion criminal settlement and a brief prison stint for Changpeng Zhao, former CEO. (Binance’s U.S. operation is making a comeback, and Zhao has been meeting with Trump family members interested in taking a financial stake in its U.S. arm at the same time he has been angling for a pardon. Watch this space!)

Law enforcement inside the IRS is shared enemy territory for virtually the entire GOP coalition, triggering as it does the party’s long-standing hostility to tax enforcement with Trump’s more specific preoccupation with strongman subversion of the rule of law. So it’s little surprise to see Koopman’s achievements suffering reversals. It was probably less expected that Cep’s encomium to Ronald E. Walters, the hypercompetent leader of the National Cemetery Administration within the Department of Veterans Affairs, would read quite so poignantly amid the chaos unleashed by the first wave of DOGE-spurred firings and mass contract cancellations in the VA. “Our government is designed to change,” Cep quotes a former colleague of Walters, Stephen Shih, as saying, “so there will necessarily be these periods of transition, and Ron has navigated that masterfully, finding a balance between providing continuity and moving the government forward.” More winces: Shih made these reassuring remarks about Walters’s survival prospects while serving as director of the Office of Civil Rights at USAID.

The right’s hatred for the civil service contains multitudes. There’s a sociological angle—the conviction that the administrative state is under the collective control of a particular class of people zealously committed to a dangerous ideology and bent on resistance by hook or by crook to conservative governance. Trump’s iteration of this, like his iteration of all ideas, is deeply personalized, grounded in his understanding of the federal civil service as the people investigating and seeking to punish him for his crimes. The ascendant Silicon Valley strain of anti-bureaucracy, meanwhile, espouses a more avowedly demolitionist ethos in keeping with the hothouse managerial culture of tech. At base, however, the case for government administration is the case for government itself, and that is precisely what the right can’t abide.

Democracy is a double delegation game. Voters delegate the task of actually making laws to the politicians they elect to represent them. The politicians then delegate the task of executing those laws to bureaucrats. At their most effective, the grounded portraits of individual bureaucrats in Who Is Government? take us, in their hyperspecificity, all the way back to the first step of that game—the question prior to “who is government?” of “why have government?” Across the book’s accounts, we see bureaucrats engaging with problems for which free markets and private action would not be able to generate solutions on their own. “No one coal mining company was likely to fund the [safety] research that would benefit all coal companies,” Lewis notes, and in fact the market even incentivized those companies to neglect implementation of safety features for years after bureaucrats like Chris Mark had developed them—until new laws passed by Congress finally added enforcement teeth to the regulations. The FDA’s Stone created a reliable mechanism for making important information about discoveries in the treatment of rare diseases accessible to doctors when no such mechanism had earlier existed—the rareness of the diseases means “it doesn’t really pay anyone to do it,” as one biochemist remarked to Lewis. Eggers describes the work of space nerds at Caltech: “This is government-funded research to determine how the universe was created and whether we are alone in it. If NASA and JPL were not doing it, it would not be done.”

Ordinary people aren’t expected to devise on their own the collective answers to every failure in health care or mine management or space exploration—that’s what Congress is there to do. But members of Congress aren’t expected themselves to build the clearinghouse for rare disease treatment, or devise the software that determines the right roof reinforcement for a specific coal mine, or build panoramic space telescopes that suppress starlight so far-flung planets can be detected—that’s what civil servants are there to do. The tasks that lawmakers ask to be performed in their legislative language are legion, complicated, specialized, and ongoing. That’s why there are a lot of bureaucrats, and that’s why they enjoy, to a greater or lesser extent, some degree of autonomy to do their jobs. “What the government job gave me was the freedom to do these things,” Mark the mine engineer tells Lewis. “No one told me to do it. No one could have told me to do it.”

The autonomy of unelected government actors is precisely what makes people nervous—if the frontline agents in democracy’s delegation game go rogue against their principals, democracy breaks down. But for the right, this is specifically dangerous because it views the left as dominating the bureaucracy in the same way it dominates media, major cultural institutions, and higher education—the deep state is rogue on behalf of the right’s enemies. When JD Vance said in 2021 that the next Republican president should “fire every single mid-level bureaucrat, every civil servant in the administrative state, replace them with our people,” this was what he was getting at. For all the hype about inefficiency and waste, Musk got closer to the heart of what’s motivating the new assault when he declared USAID “a viper’s nest of radical-left Marxists who hate America.”

Who Is Government? is a selective and decidedly boosterish portrait of the federal bureaucracy, but it is still worth noting just how undetectable the right’s caricature is in the workers it profiles. If there are recurring attributes that do come up, pointing to a broadly distinct occupational culture, they are an earnest sense of service mission and a reflexive aversion to attention and credit. “No one at JPL—no one I met, at least—was willing to take credit for anything,” Eggers remarks, while Lewis ponders civil servants’ general lot as “the carrots in the third-grade play.” A public service orientation predominates in surveys of civil servants’ occupational motivations—unsurprisingly, given their frequently low and flat compensation structures compared to private-sector work. From day one, moreover, a conception of public service as at once nonpartisan and deeply collaborative is actively inculcated, as sociologist Jaime Lee Kucinskas documents in her new book on civil servants during the first Trump presidency, The Loyalty Trap: Conflicting Loyalties of Civil Servants Under Increasing Autocracy:

Once on the job, as one former EPA employee described, employees undergo so-called cultural climatization, where they learn from supervisors and colleagues that to be a public servant means upholding the duties and norms of nonpartisanship and collaborative dialogue with supervisors and other stakeholders across the government. Decision making is grounded in collective deliberation, reason, and expert knowledge. They also learn emotional forbearance and discretion. This employee described “a lot of groupthink,” at the EPA. “That’s part of what makes it work.”

If civil servants tend to evince an aversion to making waves, that’s in part a function of the complicated mix of authorities and goals they’re tasked with serving. “It is not easy for career civil servants to navigate the various obligations of their roles,” Kucinskas notes, “which expect them to serve as a source of stability in the government, serve presidents and their specific agendas, uphold the law, and adhere to their professional normative and ethical obligations in their agencies—all at once.”

The pressures American civil servants face also stem from the fact that, contrary to the right’s nightmare, the U.S. bureaucracy is distinctively nonautonomous—uniquely permeable by and subject to the influence of outside political forces and organized interests. (This is true even under normal circumstances, when a world-historically rich tech oligarch isn’t empowered to wander agency to agency yanking out wires.) It is a truism of scholarship on U.S. political development, but of no less momentous importance for being so, that the United States democratized before it bureaucratized. Whereas, through the crucible of continual warfare, Western European nations developed powerful and professionalized administrative states long before they transitioned to mass democracy, the United States across the nineteenth century grew as a sprawling democratic polity and economic juggernaut without building out a proportionally large and powerful central administration in government. (What the national state did in the nineteenth century—and it did plenty—it typically did indirectly and invisibly, delegating to states, civil society actors, and private individuals the task of carrying out major state projects like continental expansion and capitalist development.) The preexistence of a precocious and robust democratic polity meant that once Congress finally began, piece by piece, to construct new bureaucratic institutions staffed by large merit-based cadres of experts, it was compelled continually to ensure that this new administrative state would be reined in, watched over, and suffused by political forces.

In comparative perspective, the American civil service is lean, and leaned on.

In comparative perspective, the American civil service is lean, and leaned on. U.S. federal agencies include a vastly higher number of political appointees—approximately 4,000 officials—who occupy several more layers of organizational leadership than is typical in other long-standing democracies. The ranks of the federal civilian workforce, hovering around three million, have barely budged in absolute numbers and outright declined as a share of the American labor force for the last 50 years—during the same period that government expenditures have nearly quintupled. (This is why the fiscal rationale for DOGE’s assault on the bureaucracy is so absurd—you could eliminate every single civil service position in government, and the impact of the savings, about 5 percent of overall federal spending, would barely rise above a rounding error.) The work that civil servants perform, moreover, is enmeshed in thickets of political intervention and interest-group pressure. As formalized in the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, the process by which bureaucrats formulate rules to implement legislation entails mechanisms for public input and review and extensive opportunity for appeal through litigation. And in their day-to-day tasks, the procedural red tape so often bemoaned as emblematic of bureaucrats’ own inefficiency typically comes as the by-product of both Congress’s and the president’s efforts to monitor civil servants’ behavior and limit their autonomy. Little wonder they tend to keep their heads down.

As a trope about government, “waste, fraud, and abuse” is a hardy perennial, and it’s no surprise to see it now utilized in service of a right-wing government’s assault on perceived enemies burrowed in the organs of state. And just the thing that makes the bureaucratic hagiography in Who Is Government? such a novelty—the pervasive stereotype of government workers as nonentities pushing pencils on the people’s dime—would seem likely to make DOGE and the broader assault on bureaucracy good politics as well. But, remarkably, the sheer scale and careening recklessness of what the Trump administration has already executed are generating public blowback that only promises to swell as the rolling effects of service disruptions, benefit interruptions, and job terminations are felt in every congressional district in the country. In his classic account of the development of federal administrative capacity in the United States, Building a New American State, political scientist Stephen Skowronek described nineteenth-century Americans as lacking a “sense of the state”—a felt connection to a visible and pervasive government exercising power. Whether or not they’ve consciously thought about it in this way, the gambit currently being carried out by Trump, Vought, and Musk amounts to a kind of bet that Americans in the twenty-first century still lack that sense of a state—of day-to-day connections to the federal government that they’ll miss when they’re destroyed. As constituents flood town halls and congressional inboxes with complaints about lapses in VA health services, skyrocketing wait times at the Social Security phone lines, and friends and neighbors tossed out of work, that bet looks less and less likely to pay off.

Whatever its electoral cost to Republicans, however, the cost of the current ravaging of the civil service will be greater for the country as a whole. The brain drain of expertise, the wanton destruction of research and administrative endeavors built up over decades, and the shattering of the promise of job stability, which for so long has served both to compensate for the comparatively limited financial upside of civil service careers and to help incubate the kind of slow-bore achievements celebrated in Who Is Government?—such losses may be irreversible.

In announcing its report on the FEVS survey results this year, the Partnership for Public Service went ahead and noted the rampaging elephant in the room: “Against the backdrop of a new presidential administration and dozens of executive orders that seek to downsize and politicize our nonpartisan, merit-based civil service, this new data could not come at a more critical time.” Critical, perhaps—but also a bit late to be heeded: Just one week earlier, the Office of Personnel Management had announced that it would be delaying the administration of this year’s FEVS survey, typically done in May, to an unspecified later date.

The post Michael Lewis’s Paean to Federal Workers Hits Differently Under DOGE appeared first on New Republic.