Around this time last year, as then-U.S. President Joe Biden was outlining possible terms for a cease-fire in Gaza, an Israeli defense official explained to me why the military supported a pause in the fighting. The reason had little to do with the combat itself. Instead, a cease-fire offered a chance to restore the social contract between the state and the Israeli public, including the understanding that Israel should only wage wars that serve the public good and always prioritize the release of captive soldiers and civilians.

These days, as Israel marks 18 months of war in Gaza, that unwritten agreement is a dead letter. It was steadily undermined by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who chose to press on with the fighting despite mounting evidence that his war aims were unachievable—and finally shredded by his decision in March to unilaterally scrap the cease-fire with Hamas. That brief truce, brokered by the United States in January, had freed 33 hostages and held out the possibility of further releases. Instead, Israeli assaults on Gaza are back with a vengeance.

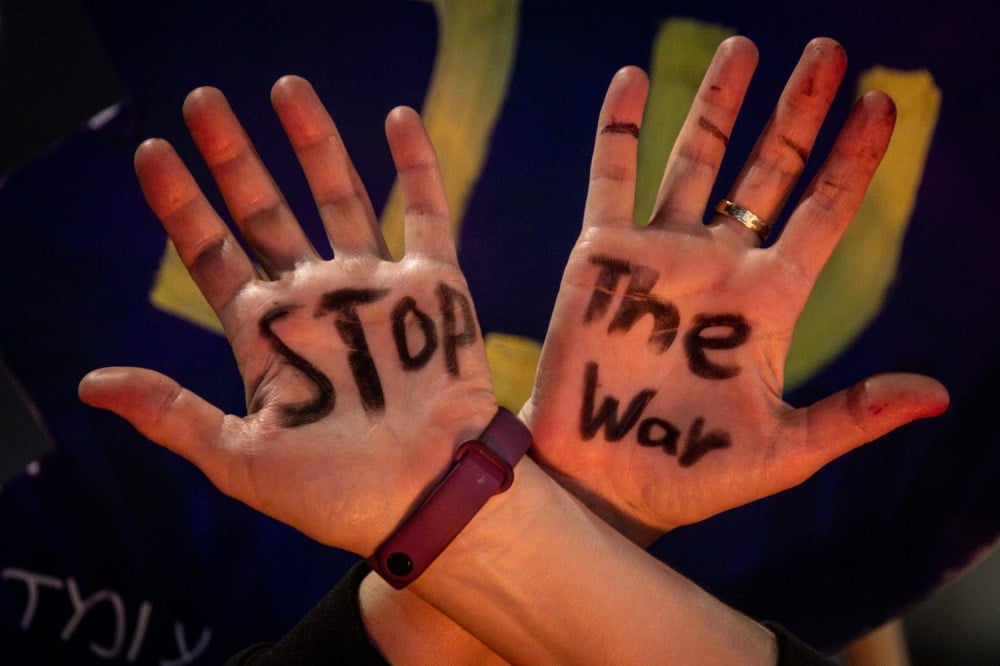

Netanyahu now vows to continue the fighting until Hamas is defeated. (Israeli bombardments have already destroyed much of Gaza but not Hamas.) But Israeli reservists are reeling from multiple combat tours since Oct. 7, 2023, and families of the hostages feel their loved ones have been abandoned. In late April, Netanyahu rejected a proposal by Hamas to free the remaining hostages in exchange for an end to the war—prompting an extraordinary response from the mother of one hostage. “Before you send your son to war, face the reality,” said Anat Angrest, addressing other parents who had gathered at a demonstration in Tel Aviv and showing a photo of her son, who was captured on Oct. 7. “Look at how my son has been abandoned and is now being sacrificed. Look, mother, at how instead of ending the war and getting my son home, they are sending your son to fight a war that is endangering them both.” This is precisely what the army hoped to avoid.

The result of all this is a domestic backlash against the war that is broader than anything Israel has seen since Oct. 7.

It started with a letter signed by nearly 1,000 mostly retired Israeli Air Force reservists in early April, just before the Passover holiday. “This war primarily serves political and personal interests, not national security interests,” the letter read. “The continued war does not help to achieve any of the war goals and will lead to the killing of hostages, IDF [Israel Defense Forces] soldiers, and innocent civilians and further erode reservist forces.” Air Force commander Tomer Bar and IDF Chief of Staff Eyal Zamir, who had tried to thwart publication of the letter, discharged the active-duty reservists who signed it. Within days, thousands more signed similar letters, including former heads of Mossad, members of special forces, Navy officers, and cyberwarfare and military intelligence teams, including hundreds who are in active reserve duty. Other letters have been issued by health care professionals, academics, and artists.

To be clear, the backlash is decidedly not a response to Israel’s excessive use of force that has killed tens of thousands of Palestinian civilians. (Although it is noteworthy that Moshe Yaalon, a hawkish politician and former military chief, described Israeli actions in northern Gaza this year as “ethnic cleansing” and condemned the state for sending soldiers to “kill babies in Gaza.”) It is mainly about prioritizing the hostages—even if it means ending the war. It is also—or perhaps primarily—a vote of no confidence in the Netanyahu government, which many Israelis believe is perpetuating the war in order to remain in power.

Polls have shown for months now that a solid majority of Israelis—even among those who voted for the Netanyahu coalition—support ending the war to release the hostages. Most Israelis understand by now that military operations aimed at freeing the hostages are more likely to get them killed. A majority now supports an Israeli withdrawal from Gaza, even if this leaves a vastly diminished Hamas in control for the time being.

The significance of this backlash isn’t just in the number of people calling for an end to the war but also in the titles some of them hold. Prominent members of Israel’s security elite are among those publicly accusing Netanyahu and his far-right coalition partners of sacrificing the hostages for political ends. In other words, this government is waging the current phase of the war in Gaza without broad public backing and against the better judgment of people who devoted their lives to the country’s security. For Israel, that is a first.

This backlash coincides with a separate but related crisis: a growing shortage of reservists. According to multiple press reports, there has been a 50 percent drop in the rate that reservists are showing up for duty since Israel resumed hostilities in March. Most Israelis are conscripted at age 18 for two to three years and perform compulsory reserve duty until age 40. Their reasons for staying away this time are varied. They include family demands, war fatigue, and especially their financial situation. (75 percent of reservists surveyed in February said the long months spent fighting in Gaza harmed them financially, and 41 percent reported that they were either fired or left their jobs.) But some are refusing for ideological reasons—whether because they distrust this government, doubt that further military operations will bring back the hostages, resent that ultra-Orthodox Jews remain exempt from army service, worry about being incriminated for war crimes, or indeed because they morally oppose how Israel has conducted the war.

This soft refusal to serve—whether for political, ideological, or personal reasons—could force the government to adapt its approach in Gaza. It might not happen overnight. But if Israel moves to take full control over all aspects of life in Gaza and resettle Israelis there, as Netanyahu’s coalition partners demand, the manpower challenge will likely grow. The government might be banking on the idea that military service remains sacrosanct and ultimately reservists will show up. Failing that, the military could be forced to pull troops from other fronts, including Lebanon, Syria, and even the West Bank.

In the long term, a trend toward dissent could have significant ramifications for the country. The Israeli military has been a “people’s army” since its inception, relying on reservists to fight short, decisive wars. In countries that depend on reservist armies, governments must take public sentiment into account. As Netanyahu’s government continues to neglect the hostages and prolong the war, the backlash is likely to grow.

The post For the First Time Since Oct. 7, a Broad Israeli Backlash Against the War in Gaza appeared first on Foreign Policy.