This year, for the first time since inviting a comedian to headline in 1983, the White House Correspondents’ Dinner promised there would be no entertainment. In that regard, it delivered.

I didn’t attend Saturday night’s dinner, partly out of principle after the White House Correspondents’ Association disinvited a comedian at the Trump administration’s request, and partly because no one invited me.

But I wrote speeches and jokes for President Obama, and then a book about writing speeches and jokes for President Obama. So I’ve spent more time thinking about the Correspondents’ Dinner than any self-respecting human should.

Starting in the Reagan era, the Dinner served as a tri-lateral summit between politicians, journalists, and celebrities. This made it, in many ways, gross. President Obama once called the evening “the night when Washington celebrates itself,” a point proven by the knowing laughter that filled the room when he said it.

But the dinner was also a celebration of the First Amendment. The leader of the free world cracked jokes—including some at his own expense—and made public commitments to uphold freedom of the press. The headliner made fun of the people in the room, including the president, without fear of government retribution.

The White House Correspondents’ Dinner may not have defended free speech, any more than a canary defends a coal mine. But it served as a public indicator—covered live on television and shared across social media—that the spirit of the First Amendment was alive and well. That’s one reason a dinner by and for White House reporters (as opposed to, say, investigative reporters or war correspondents) became America’s premiere public celebration of journalism.

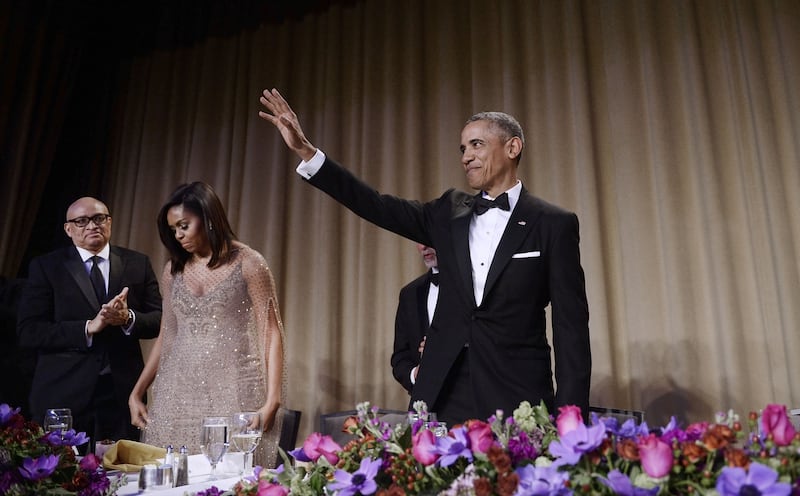

As with most D.C. institutions, the Correspondents’ Dinner exited Trump 1.0 on shaky ground. The president skipped the event for his first three years; backlash to Michelle Wolf’s monologue prompted the Correspondents’ Association to invite an historian rather than a comedian in 2019, and the pandemic cancelled the festivities entirely in 2020.

Trump’s second term is different. In February, the Correspondents’ Association announced that Amber Ruffin would be the headlining comedian. In March, while on a podcast (The Daily Beast podcast, as it happens) Ruffin called Trump’s team “kind of a bunch of murderers,” adding that false equivalency “makes them feel like human beings, but they shouldn’t get to feel that way, ‘cause they’re not.”

Trump’s White House pounced. Just as they did when going after law firms or universities, targeted the dinner’s funding, in this by attacking its corporate sponsors. Hours later, the Correspondents’ Association disinvited Ruffin and announced there would be no replacement entertainer.

You don’t have to agree with Ruffin’s comments to see the larger principle at stake. For nearly 130 years, American journalists have pledged to cover the powerful “without fear or favor.” But when it came to this year’s dinner, this year’s “celebration of the First Amendment,” America’s most visible group of journalists did the powerful a favor out of fear.

Surprising no one, the White House responded to the press corps’ capitulation by attacking it even more aggressively. Two weeks after Ruffin’s invite was revoked, the White House announced that it will effectively ban all wire services from the press pool. Trump administration officials, meanwhile, were ordered to boycott the dinner despite its absence of dangerous comedians, and even set up their own MAGA after-parties.

So without the president, the comedian, the independence to determine its own program without White House interference, or anything to show for bending to the President’s demands, what was left? Some of the dinner’s defenders will argue that dinner’s real purpose is to raise money for scholarships that support journalism students. This is true, in the same way it’s true the Met Gala exists to raise money for the Costume Institute. But pretexts aside, the Dinner is a celebration. And with little to celebrate First-Amendment-wise, the Dinner focused on celebrating its members instead.

There’s nothing wrong with organizations handing out awards to their members. The National Association of State Boards of Accountancy does it. So does the Australian plumbing and gas industry, the Maryland Society of Surveyors, and countless other, similar trade groups. But accountants and plumbers and surveyors do not bill their awards ceremonies as celebrations of our Constitutional liberties. The Little League Coach of the Year Awards don’t feature a red carpet. Neither, to my knowledge, do the Pulitzers.

I don’t know what it felt like in the room. I wasn’t there. But my understanding, from those I know who were, was that it didn’t just feel less funny than usual. It felt smaller. A cultural moment was reduced to a professional conference, albeit one where their participants wear black tie. A night that once highlighted the free press’s importance instead highlighted its inability to come to its own defense.

Trump is going after far more important targets than the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. What’s one more dead canary in a coal mine full of dead canaries?

In one respect, though, the Correspondents’ Association stands out from other groups that have caved. Because the controversy occurred just a month before the event, we can see, in close to real time, what happens to institutions that capitulate to President Trump.

The members of the WHCA aren’t being shipped to a gulag in El Salvador. The Dinner still exists. But only as a shell of its former self. The institution was preserved—but only at the cost of the qualities that made it worth preserving in the first place.

The post Opinion: Why White House Correspondents Got the Shriveled Party They Deserved appeared first on The Daily Beast.