Months into his papacy in 2013, Pope Francis was asked about gay priests, and he responded, “Who am I to judge?” Across the United States, Catholics and non-Catholics alike took a collective gasp.

For years the Roman Catholic Church in the United States had deeply aligned with the religious right in fierce conflicts over issues like abortion, gay marriage and contraception. But Pope Francis wanted a church “with doors always wide open,” as he said in his first apostolic exhortation.

Words like these made the new pope a revolutionary figure in the United States, in both the Catholic Church and the nation’s politics. He challenged each to shift its moral focus toward issues like poverty, immigration and war, and to confront the realities of income inequality and climate change. Pope Francis offered a progressive, public Catholicism in force, coinciding with the Obama era, and at the beginning of his pontificate, he moved the U.S. church forward from the sex-abuse scandals that roiled his predecessor’s pontificate.

He pushed church leaders to be pastors, not doctrinaires, and elevated bishops in his own mold, hoping to create lasting tonal change in the church through its leadership. He gave voice to the growing share of Hispanic Catholics, as the American church grew less white, and appointed the first African-American cardinal. He allowed priests to bless same-sex couples and made it easier for divorced and remarried Catholics to participate in church life.

In doing so, he captured the imaginations of millions both inside and outside the American church who had long felt rejected. At a time of increasing secularization, the world’s most visible Christian leader gave hope to many U.S. non-Catholics who saw in him a moral visionary while much of public Christianity in America took a rightward turn.

“He made the church a more welcoming place,” said Joe Donnelly, former Democratic senator from Indiana, who was the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See under President Biden. “For Americans of all different economic strata, for divorced Americans, for basically everyone in our country, his arms were always open.”

Yet it was this same transformative vision that ultimately fueled the rise of an energized conservative Catholic resistance, which further divided the church in America. Pope Francis’ cardinals had a minority voice among U.S. bishops, and in the final years of his papacy, powerful conservative lay Catholics once again made ending abortion their dominant priority. Conservative Catholic backlash to values like Pope Francis’ helped return President Trump to the White House, with Vice President Vance, a Catholic convert, by his side, advancing priorities that conflicted with Pope Francis’.

Midway through his papacy, parishes were roiled by revelations that church leaders in the United States covered up sexual abuse for decades, reminding many of their distrust of the church at every level. The Pope’s regained popularity diminished, as American bishops faced a host of federal and state investigations. Many Catholics grew weary waiting for the Vatican to solve the continuing crisis, with more than a third considering leaving the faith, according to a Gallup poll.

Pope Francis offered some reforms, and in a high profile case expelled Theodore E. McCarrick, a former cardinal, from the priesthood after the church found him guilty of sexually abusing minors and adult seminarians over decades. It appeared to be the first time a cardinal was defrocked for sexual abuse. But for many people, these actions were not enough.

With his death on Monday, Pope Francis leaves behind an American church that is pulled in opposite directions, on social issues, politics and tone, mirroring the polarized country it inhabits.

Still, in the end, the sense of Pope Francis’ pastoral legacy remains palpable in many American pews.

“How he speaks about contemporary issues, I think it has allowed a lot of people in our community to feel seen and heard,” said Father Matthew S. O’Donnell, 38, pastor of St. Moses the Black Parish, on the South Side of Chicago. “No doubt the church has changed. Speaking as a priest, I think that what he has called the church to be is pastoral.”

The United States itself was not Pope Francis’ main priority. He visited the country only once, in 2015, and he intentionally arrived from Cuba, one more way to show his global priorities. The United States has the fourth largest Catholic population in the world, behind Brazil, Mexico and the Philippines. But it is a small fraction of the church’s more than one billion Catholics, many of whom live in the peripheries he sought to elevate.

But Pope Francis also knew the power of the U.S. church on the global stage, and used and challenged it as he saw fit. Though the church is a religious institution, guiding 52 million U.S. Catholics, it is also a political body, and his tenure intersected with changes in American politics.

He oversaw the church during a transformational decade of U.S. leadership. At the start, he aligned himself with former President Obama’s foreign policy, showing that Rome and Washington could work together on progressive issues, not simply conservative ones. His Vatican helped secretly broker the United States’ détente with Cuba. He also supported the Iran nuclear deal and Palestinian statehood. For many it felt as though the overlapping Obama and Francis eras signaled a progressive trajectory on the world stage.

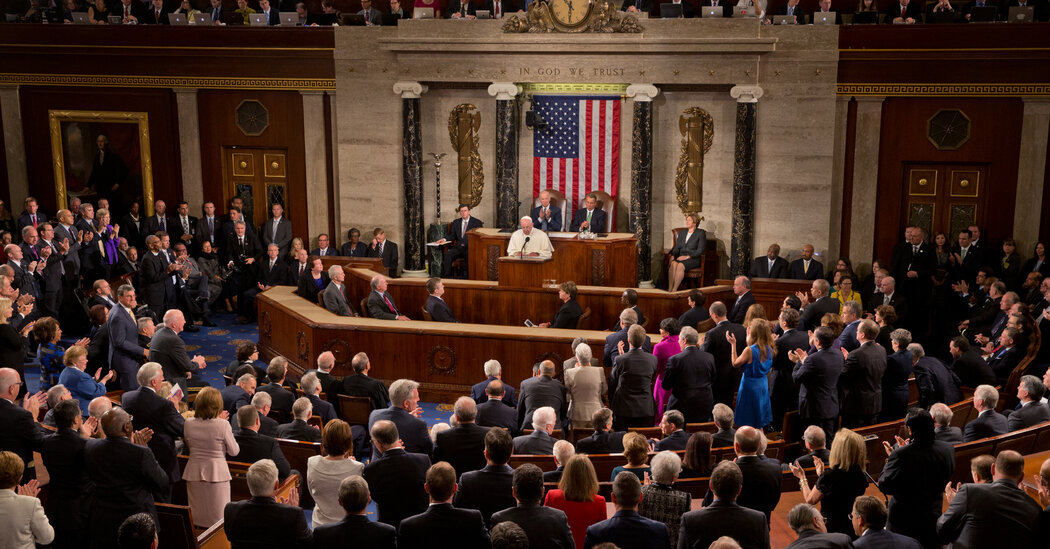

Pope Francis became the first and only Pope to address Congress, where he pleaded for unity to solve global crises, and received standing ovations. He challenged both political parties — Democrats to support religious liberties and the value of human life, and Republicans to embrace immigrants and the need for environmental protections. He left the chamber to serve lunch at a soup kitchen.

His visit showed his immense popularity, as Catholics and non-Catholics alike filled streets in Washington, New York and, finally, Philadelphia, where the 10,000 tickets for his Mass were snapped up in 30 seconds.

Beginning when Donald Trump ran for president in 2016, Pope Francis challenged his actions and rhetoric toward migrants, questioning his purported Christian values.

“A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian,” Pope Francis said, hours after he celebrated a 200,000-person Mass in Mexico along the U.S. border at the time. By the Rio Grande, he laid flowers to remember those who died trying to cross, as U.S. security officials watched from the other side.

“He used his gravitas in the beginning formidably,” said Ken Hackett, who was the U.S. Ambassador to the Holy See under Mr. Obama. “Really in those early years, he made a difference.”

At the same time, Mr. Hackett said, “in a way, he’s aggravated some of the ideological tensions in the United States.”

A stark partisan divide emerged among American Catholics over the course of Pope Francis’ tenure. At the start, Catholic Republicans and Democrats both held him in high regard, according to the Pew Research Center. But by 2024, about 90 percent of Catholic Democrats viewed him positively, compared with just 63 percent of Catholic Republicans.

Conservative frustration was part political, part religious. Often it was born of what conservatives perceived as Pope Francis’ fixation on U.S. policies he did not like, like Mr. Trump’s mass deportation plans, instead of other issues like human rights abuses in China.

“It seems to me we get a disproportionate amount of the flak that is coming over from the Holy See,” said Mary Ann Glendon, a legal scholar who was the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See under George W. Bush.

“Popes are human beings like all the rest of us, and I think he does have a kind of reflexive, less-than-friendly attitude toward El Norte,” she said, referencing the Global North.

When former President Biden, who regularly attends Mass and has spent a lifetime steeped in Catholic practice, was elected, U.S. bishops advanced a conservative push to deny Mr. Biden communion because of his support of abortion rights — even after the Vatican told them not to.

“The pope never really took him to task for that,” said Jim Nicholson, who was the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See during President George W. Bush’s first term. Supporting abortion, he said, “is antithetical to principled teaching of the church.”

Some American Catholics felt that Pope Francis too often left things unclear, particularly over issues of sexuality, by gesturing in multiple directions: He allowed priests to bless gay couples, reaffirmed church teaching that marriage is between a man and a woman, apologized after reports that he privately used a slur for gay men and restated the church’s instruction that men with “deep-seated homosexual tendencies” should not become priests.

But Pope Francis’ message resonated easily in parishes like St. Maria Goretti in New Orleans, a largely African-American church with Filipino, Vietnamese and Hispanic families.

“Black Catholics have always been hyper-focused on ‘the least of these,’” said Father Daniel Green, 39, the priest, who was ordained just weeks into Pope Francis’ papacy. “For many of us, we said, ‘Finally somebody is speaking about what we are speaking about, and not just doing it as a tangential.’”

He remembered the power of Pope Francis’ early tone-setting statement, “Who am I to judge?”

“Whether I think you are welcomed or not, God wants you here,” Father Green said, describing the phrase’s meaning. “I do think that is the gift of his ‘Who am I to judge?’ — that God has created each and every one of us, and the church should be accessible to all of us.”

Elizabeth Dias is The Times’s national religion correspondent, covering faith, politics and values.

Ruth Graham is a national reporter, based in Dallas, covering religion, faith and values for The Times.

The post Pope Francis’ Legacy in the U.S.: A More Open, and Then Divided, Church appeared first on New York Times.