CRUMB: A Cartoonist’s Life, by Dan Nadel

R. Crumb, the underground cartoonist, bumped into things when he was young. Before his eyes were tested in first grade, and he was fitted for Coke-bottle glasses, he could perceive neither depth nor distance. His parents thought he was clumsy. With no sense of spatial dynamics, he had to think his way into the world rather than enter it the way most of us do, by simple intuition. When he began to draw, it was as if he was already dipping into a deeply personal and self-replenishing reservoir. He was unusual — a weirdo, to borrow the name of one of his comic book series — right from the start.

It’s been nearly 60 years since Crumb helped define the visual iconography of late-1960s psychedelia, with surreal imagery that’s as instantly recognizable as a Deutsche Grammophon record label and that seemed to come from the past and the future at the same time.

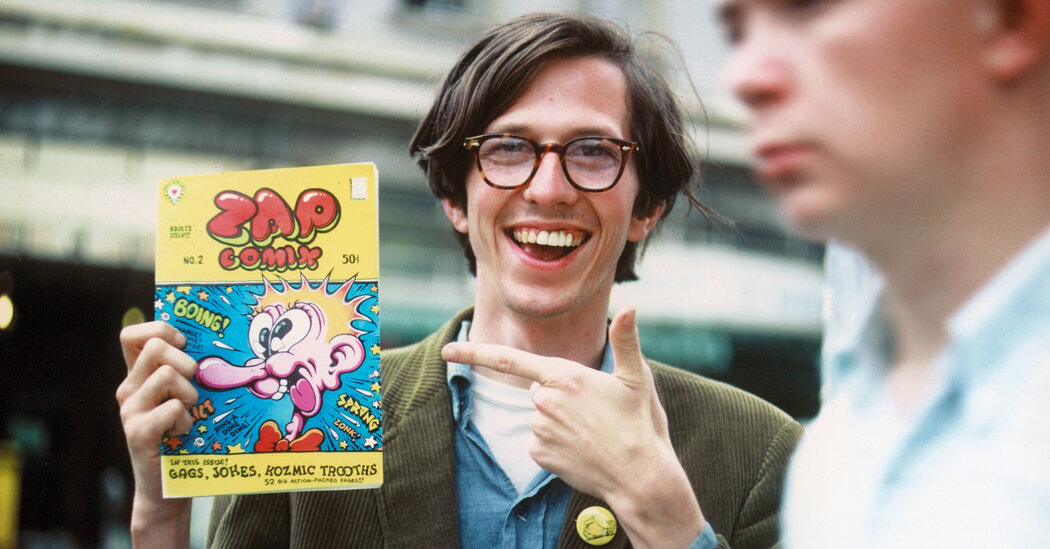

His Zap Comix, not for kids, read like a stoner version of the Sunday funnies and gave us the loping and big-footed dudes in his “Keep On Truckin’” panels and the bald, bearded and semi-baffled mystic Mr. Natural, who in one strip was kicked out of heaven for telling God it was “a little corny.” There was his version of Felix the Cat, later adapted into the first X-rated animated film, and the cover he drew for “Cheap Thrills,” the hit second album from Big Brother and the Holding Company, with Janis Joplin — the one with “Piece of My Heart” on it.

It’s been more than 30 years since Terry Zwigoff’s eye-popping documentary “Crumb” (1994) reintroduced him to the world and fleshed out his sexual fetishes (notably his inclination to ride piggyback on big women’s backs, occasionally uninvited), his demons and his obsession with old-timey 78 r.p.m. records. The movie humanized him — it made him seem like an earnest citizen out on a peculiar limb.

The documentary also, as if interpreting the freak-show nature of many of his cartoons, the coarse Russian fairy tale vibe of them, set him alongside his troubled and profoundly eccentric family, which included his often institutionalized mother and a sibling who reclined on beds of nails and regularly passed a 29-foot strip of cotton through his digestive system, in the mouth and out the anus.

Is the world ready, as if in every-30-years installments, for another rocky wagon ride into Crumblandia? I was, if only because Dan Nadel’s new book, “Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life,” is a definitive and ideal biography — pound for pound, one of the sleekest and most judicious I’ve ever read. He’s latched onto a fascinating and complicated figure, which helps.

But there’s more going on here. Nadel, a museum curator who has written two previous books about artists and cartoonists, is an instinctive storyteller, one with a command of the facts and a relaxed tone that also happens to be grainy, penetrating, interested in everything, alive. He knows exactly when and how long to pause and tweezer in background information, a skill that flummoxes so many biographers. This machine kills boredom.

“Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life” is an official biography, written with Crumb’s permission. He fact-checked the final manuscript, though he had no control over the final text. He imposed one condition, Nadel writes: “that I be honest about his faults, look closely at his compulsions and examine the racially and sexually charged aspects of his work. He would rather risk honesty and see if anyone could understand than cooperate with a hagiography.”

Robert Crumb’s childhood was nomadic. He was born in 1943 in Philadelphia, but his father was in the Marines and the family (Crumb had four siblings) followed him from base to base. Crumb and his older brother, Charles, took to cartooning early, on the bedroom floor, their materials stuffed into coffee cans and cigar boxes.

They deplored superhero comics, which were filled with intimidators solving problems with their fists. They were into oddball strips, like Walt Kelly’s “Pogo” and the early work out of Disney. When he was in high school in the 1950s, where he was painfully self-conscious, an absolute outsider, Crumb began to tune into discontented voices such as those of Lenny Bruce and Mort Sahl. Mad magazine was another revelation. He and Charles began sending their homemade comic books out into the world.

He skipped college but lit out for Cleveland, where he got a job drawing for a major greeting card company. He married his first wife, Dana Morgan, when he was 21 and she was 18. They took LSD together and it permanently shifted the contents of his mind, in a manner he liked — it gave him a direct passage to his subconscious.

He began to draw for alternative newspapers. He and Dana drifted out to San Francisco, where he embraced the counterculture, and it embraced him. “Keep On Truckin’” appeared in Zap Comix No. 1, which hit the streets in 1968. The image was a widely bootlegged phenomenon, to the extent that Crumb would see it on the mudflaps of passing trucks.

He was a sort of knowingly inverted dandy, to borrow Walker Evans’s description of James Agee. He wore corduroy trousers, baggy pants, thick spectacles and fedoras. Joplin advised him to stop dressing like a dude out of “The Grapes of Wrath.” He was “beak nosed,” Nadel writes, “Adam’s apple ready to bob in distress.” He was not quite made for this world.

Crumb’s underground comics were transgressive comics — they were dirty. Zap No. 4, which came out in 1969, contained a strip called “Joe Blow” about a family that cheerfully and explicitly commits nearly every variety of incest imaginable and sent a signal, Nadel writes, “that the American nuclear family was not well.” Zap No. 4 was the first comic to be declared obscene. Lawrence Ferlinghetti was arrested in his City Lights bookstore for selling it.

Crumb’s sudden fame drove him and his wife out of San Francisco. They settled up north in California’s rural Potter Valley, where they slowly developed a commune of sorts. They had an open marriage, of which Crumb took more advantage than Dana did. Both had affairs, but Crumb had more of them, with some later ones lasting decades. He had a physical type: big haunches, bold posterior.

His sexual obsessions don’t swamp this biography, but they linger near the surface. Crumb carried a lot of baggage. He let his warty, untutored id loose in his work. He had a sense of himself as, Nadel writes, “a grotesque ectomorph.”

He sometimes drew comics about domination, about rape, about women without heads who seemed to be little more than pieces of meat. “He was stuck between shame and desire; the spiritual and material; worship and hatred,” Nadel writes about some of these cartoons. “They are also curiously devotional, drawn with great care and attention, as though Robert was mesmerized by his own fantasy.”

Nadel presents the voices of women who were appalled; he cites just as many who ardently defended him, who felt that women have masochistic fantasies too, and that no one should be in the business of regulating fantasies. Crumb certainly did not run a P.R. campaign on behalf of his own psyche. He tinkered in his work with ugly racial stereotypes. These drawings deeply troubled many of his liberal cartoonist friends. His work was purging satire, he insisted, and others, including the poet Ishmael Reed, agreed with him.

He became his own best character in his work; he was both ventriloquist and dummy.

The second half of this biography shows us Crumb mostly running away from things, first in Potter Valley and later in rural France, where he moved with his second wife, Aline Kominsky, with whom he frequently collaborated. Too much socializing made him squirm. He’d often start drawing in the middle of a busy party.

He ran from fame. He was determined not to be perceived as a joke that 1968 left behind. He avoided Jane Fonda and Roger Vadim when they wanted to make a movie with him. He turned down an opportunity to play banjo on “Saturday Night Live” with his band, which sometimes went by R. Crumb and His Cheap Suit Serenaders. He declined a $10,000 offer to draw a Rolling Stones album cover. He blocked most attempts to commercialize his work and characters.

Over the decades he slowly began to feel that he’d run out of original ideas, though the sketchbooks he filled over the decades prove otherwise. Still, he more often illustrated the work of other writers — notably Harvey Pekar in the autobiographical and blue-collar “American Splendor” series, but also James Boswell, Jean-Paul Sartre, Franz Kafka, Charles Bukowski and the Book of Genesis. He drew dozens of photorealistic and often solemn portraits of the long-forgotten musicians he so loved.

There are a lot of road trips in this biography. Crumb was too dyslexic to learn to drive. He enjoyed the existential state, Nadel writes, of being the “eternal passenger.” He took two stabs at being a father, a role for which he felt ill equipped, and did a bit better the second time around. His second marriage was an open one, too. Aline died in 2022, at the age of 74.

Nadel is a canny visual reader of comics, and he traces Crumb’s influence on a long line of cartoonists, from Art Spiegelman and Matt Groening to Daniel Clowes, Lynda Barry and Seth. “Every cartoonist has to pass through Crumb,” Spiegelman tells him. “What happens when you encounter Crumb is like the accelerated evolution scene in ‘2001.’ You had to pass through him to find out what your voice might be.”

CRUMB: A Cartoonist’s Life | By Dan Nadel | Scribner | 458 pp. | $35

Dwight Garner has been a book critic for The Times since 2008, and before that was an editor at the Book Review for a decade.

The post A Cartoonist Who Tapped His Own Psyche and Found America’s Unruly Id appeared first on New York Times.