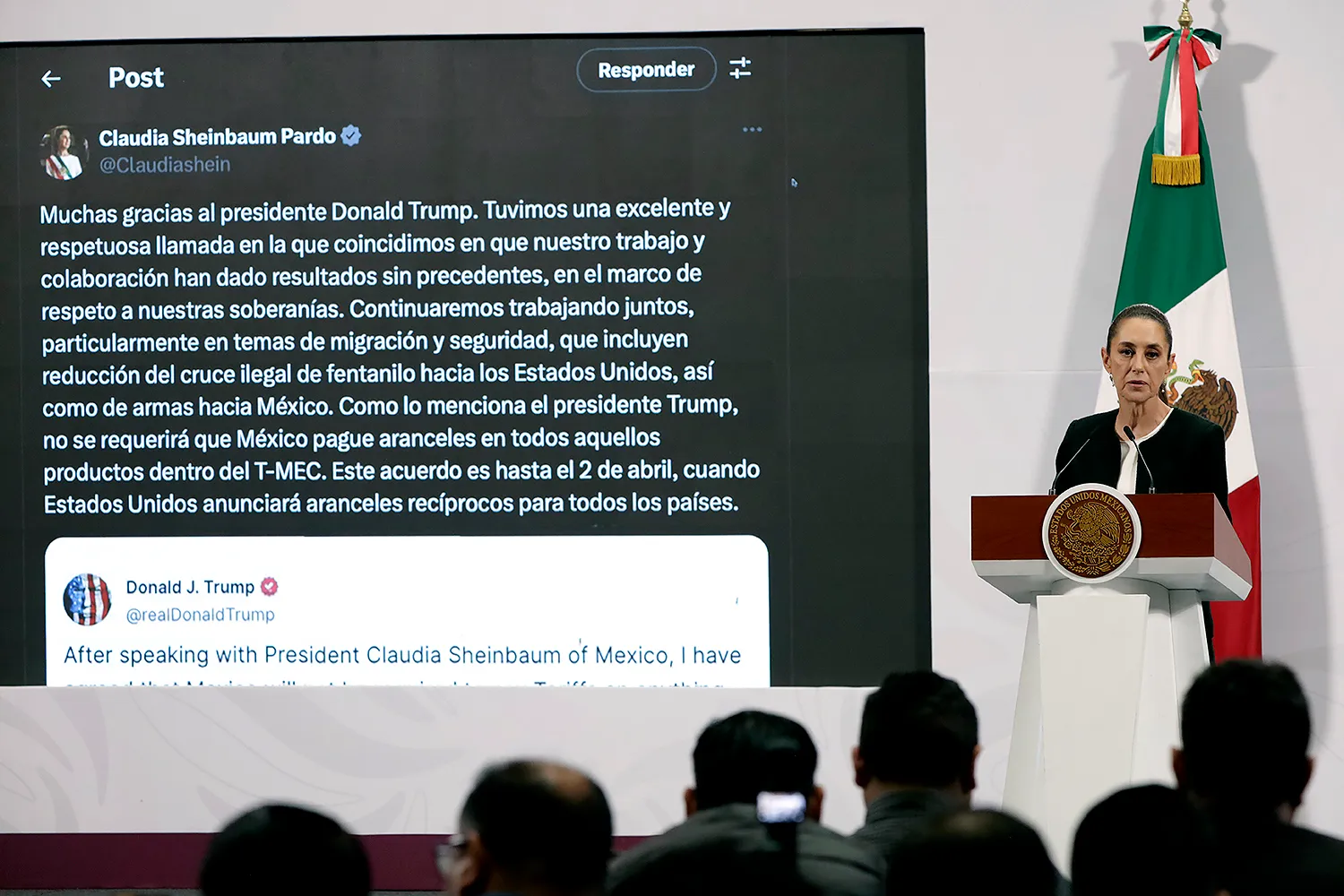

The first months of President Donald Trump’s return to the White House have been disorienting. Talk of making Canada the 51st U.S. state and acquiring Panama and Greenland by force have been shocking. Trump’s willingness to implement tariffs against longstanding allies and align with Russia have bewildered many supporters. His attacks against international norms, rules, and institutions are destabilizing.

U.S. foreign policy seems to be driven by the nakedly self-serving whims of an ill-disciplined president. Restraints on power have fallen away. Democracy is in retreat. So, how should the United States and other countries govern their international engagements amid such tumult?

One place to look for guidance is Stoicism, a major philosophical school of the Hellenistic period. While Stoic ethics focus chiefly on personal virtue, they can also apply to foreign policy. In ancient Greece and Rome, many Stoics were active in social as well as political life. It is a philosophy for the real world, not just a lecture hall. Indeed, current foreign policymakers in the United States and beyond should heed six Stoic lessons in a turbulent world.

First, Stoicism centers the pursuit of virtue. Stoics identify four cardinal virtues: justice, fortitude, temperance, and prudence. Justice, rendering unto others what they deserve, according to Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher Marcus Aurelius, is the source of all other virtues and should guide conduct. Once we have prudently identified the just path, fortitude and temperance are required to follow it.

For Stoics, virtue has a universal, even cosmopolitan, application. This is crucial for understanding Stoicism’s foreign policy implications. The ancient Roman Stoic philosopher Seneca, for instance, likened the madness of war to manslaughter or murder. Similarly, Epictetus, a slave at the Roman court who became a Stoic philosopher, viewed war as a frequent occasion for vice, especially when driven by greed and ego. While many Stoics engaged in warfare, and the philosophy itself is not pacifist, the ethical criteria for what might be termed a virtuous war are strict. Such a war conforms to a stringent application of “just war theory” and the principles jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and jus post bellum—just cause in starting a war, morally justifiable conduct during war, and moral responsibility after war.

A Stoic foreign policy would have little patience for politics that favor expediency over morality or for an unprincipled, ill-disciplined approach to world affairs. Power is never the objective; it is always a means to pursue the just. While determining what is just is complicated, it is probably less difficult to pursue than sometimes assumed.

Easier still, perhaps, is identifying unjust behavior. Using power to serve leaders’ narrow self-interest is unjust. As is the current unconcern for the planet we’ll leave future generations. A Stoic foreign policy might embrace something akin to American political philosopher John Rawls’ “veil of ignorance”—a thought experiment that asks what conditions you’d wish to prevail in society, if you were to be born into it again with your class, race, gender, and so forth unknown to you.

Second, Stoicism pursues the common good via institutions. Self-mastery and discipline are means to a better society. The Roman senator and Stoic Cato the Younger argued forcefully in support of traditional Roman institutions against the predations of dictatorship, decadence, and power. Well-functioning institutions check the abuse of power and guard against tyranny. For Aurelius, “What injures the hive injures the bee.” The inverse is also true.

In foreign policy, mistrust of power and emphasis on institutions runs against the current assault on the rules-based international order. Attacks on international humanitarian law and growing openness to recognizing Russia’s gains from territorial conquest—all to suit short-term political interests—undermine institutions. The will to power must be tempered by the pursuit of virtue. Stoics oppose the self-interested exercise of power by leaders little concerned with the wider good. Cato saw institutions as essential constraints on the naked exercise of power.

Third, the Stoics draw a stark line between things within our control and things beyond it. Epictetus called the factors in human experience outside our direct control “externals.” He advocated concentration only on influenceable matters. The aim is stillness, or ataraxia, in the face of tribulation.

Stoic foreign policymakers direct their attention and efforts to what they can control. In 2023, then-U.S. National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan underlined “the domestic sources of national strength.” Foremost among these is ensuring economic vibrancy and social cohesion. This approach also justifies a strategic and intentional emphasis on diplomatic choice. States position themselves deliberately within intergovernmental networks by prioritizing and cultivating some international relationships over others. They can contribute to global public goods and maintain international order through jointly reinforcing the rule of law in international life and collective security.

Foreign policy outcomes are only partially under the control of policymakers. They control their preparation, decision-making, level of effort, and actions. Results, however, are usually outside their control. Stoics learn to detach from outcomes and focus on the process. The Stoic principle amor fati—love of fate—applies here. This allows for risk-taking and entrepreneurship in policy. Policy advice should accord fearlessly with truth and virtue, even when it is likely to be rejected. Stoics have little regard for political pandering and careerism.

Fourth, within that sphere of control, Stoics emphasize the need for reflection. Rather than an end-state, Stoics seek constantly to refine themselves to make sure their actions are matching their ideals through self-reflection. Aurelius’ Meditations—probably the most famous Stoic text—are his personal journals, not intended for publication. They paint a vivid picture of someone struggling to live a just life.

Stoic foreign policy would be guided by a similar, reflective ethos, embodied in good policy planning and strategic analysis. In today’s social media-dominated world, there is less time for careful consideration and analysis. Decisions are made on the fly. Foreign policymaking has become strikingly reactive, shaped by social media. Recent U.S. tariff policies appear to be driven more by presidential impulse than by serious deliberation among responsible officials. The role of the diplomat has been transformed. In many such instances, Stoics maintain, the best policy response is silence—at least at first.

Former U.S. diplomat William Burns, who served as CIA director during the Biden administration, has said that foreign policymakers also need to do a better job of learning from history. This can help them to diagnose the stakes and risks associated with policy. The military, Burns wrote in his memoir, “has long embraced the value of systematic case studies and after-action reports. Career diplomats, by contrast, have tended to pride themselves more on their ability to adjust quickly.” Today’s diplomats are too often strangers to history.

The historian Margaret MacMillan, for instance, has shown the risks arising from the neglect of history in U.S. foreign policy in the lead-up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. An assessment of the British interwar experience in Iraq would, MacMillan maintains, have disabused policymakers of any notion that they would be welcomed as liberators. History can thus alert policymakers to future dangers. This parallels the Stoic practice of premeditatio malorum: considering troubles that may lie ahead.

Fifth, those that find themselves in positions of power must be governed by integrity through the pursuit of virtue. Concern even for one’s life and reputation are intolerable impediments to virtue. The Socratic ideal, uncompromising even to martyrdom in fidelity to the truth, inspires much Stoic philosophy. Leaders should thus be indifferent to potential outcomes and the desire for power.

This emphasis seems alien to modern sensibilities. The self-interested will to power among leaders is assumed and widely condoned in the United States and much of the world. The frequent falsehoods uttered by public officials has led some to question whether morals matter in public life. The blatant cynicism of Trump using national security as justification for tariffs on Canada is another example of obvious distortions guiding policy.

The Stoics, in contrast, were servants to the common good. In reading Aurelius or Seneca, each statesman grapples with temptations to abuse their position and status. Aurelius, for instance, exhorts himself to “fight to be the person that philosophy tried to make [him].” He was concerned with supporting the weak within his society. He wanted to avoid becoming Caesarified, tainted by the privileges of his office.

In statecraft, leaders should thus govern their behavior, courageously and prudently, toward the pursuit of the good rather than their own political interest and the temporary esteem of the crowd. All political careers end. Stoics reminded themselves to govern with this in mind through the phrase memento mori, meaning “remember, we must die.” When leaders abandon long-term, enlightened interest in favor of short-run, narrow political wins, they usually do it at the expense of the public good.

Sixth, Stoics see obstacles as drivers for growth in virtue. Aurelius said, “The impediment to action advances action, what stands in the way becomes the way.” For Stoics, life is not about avoiding hardship. The difficulties of life enable growth. The founder of Stoicism, Zeno of Citium, a wealthy merchant, lost everything in a shipwreck. It was only after misfortune that he discovered philosophy and made his mark on the world.

Though much appears bleak in the current context, Stoics would see an opportunity to improve our condition. Epictetus reminds us that while events are beyond our control, we can control our response to them. International crises often precede change. They contain the seeds of renewal. The fact that the Stoic emphasis on justice and virtue come across as idealistic or quaint today is telling. Stoic foreign policy casts an unflattering light on the current global moment. The Stoic instinct here is to seize the opportunity for change.

Trump’s presidency challenges many certainties about world politics. Yet Stoicism provides a classical corrective. It helps to orient us in disorienting times. The emphasis on the pursuit of justice and the common good are reminders of how far public discourses have strayed from these ideas. The Stoics remind us of the necessity of virtue in public affairs and in foreign policymaking. They remind us also of the centrality of institutions in disciplining the abuse of power and the fortitude needed to reinforce global rules.

The post What the Stoic Philosophers Can Teach Today’s Policymakers appeared first on Foreign Policy.