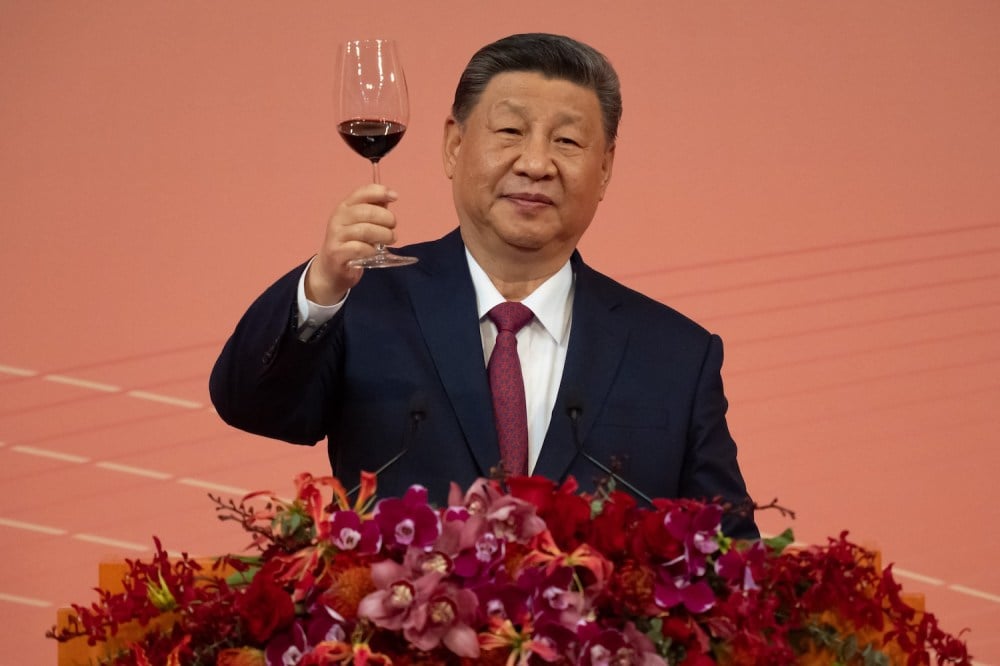

Not long after China’s leader, Xi Jinping, rose to power in 2012, close observers grew puzzled at how readily he squandered many of the advantages that the country had accumulated over decades of low-friction diplomacy and world-beating economic growth.

Early in his rule, Xi stepped up aggressive moves to claim territorial rights over virtually the entire South China Sea. China also began to accelerate the modernization of its armed forces, rolling out new aircraft carriers and other military technology, and Xi alarmed neighbors with his exhortations to the military to prepare to not only fight, but also win, wars.

At home, Xi began a sweeping anti-corruption drive that quickly looked like a campaign to cow critics and potential rivals. Soon, the regime expanded this political offensive to further constrain speech, and then to bully and humiliate the heads of some of China’s most successful businesses, such as Alibaba, whose fast growth and innovation had helped power the country’s rise.

Many Chinese people justified authoritarianism by turning to the familiar argument that the concentration of power in a disciplined executive can get things done in ways that are not possible amid the palaver and chaos of democracy. For years, Chinese graduate students in my classes boasted about this systemic advantage, but that ended with the suffocating atmosphere of Xi’s crackdown and the alarming economic slowdown that came with it.

Suddenly, conversations turned to what political theorists call the “bad emperor” problem. As a new generation of young adults bemoaned the loss of an era of nearly certain opportunity, they began to see life under authoritarianism as a matter of sheer luck. In a blink, they realized, a seemingly enlightened dictator could be replaced by a rash and benighted despot. For those who experienced this pendulum swing, authoritarianism had a crucial disadvantage: Unlike in democracies, which can vote governments out, the people have no recourse but to ride out their bad fortune and hope for a better successor.

Yet this is not just a problem inherent to authoritarianism. In recent days, it has become increasingly obvious that the world’s oldest and most powerful democracy now faces the bad emperor dilemma.

With each passing week, the United States’ vaunted system of checks and balances has shown itself to be largely impotent in constraining U.S. President Donald Trump’s power. As one Financial Times columnist recently put it, his administration is “engaged in a comprehensive assault on the American republic and the global order it created. Under attack domestically are the state, the rule of law, the role of the legislature, the role of the courts, the commitment to science and the independence of the universities. … Now, he is destroying the liberal international order.”

And while most reelected democratic leaders feel hemmed in by term limits, Trump has become more reckless in his second term, repeatedly raising the specter of extending his power beyond the eight-year constitutional limit.

Ironically, some of Trump’s most foolhardy actions have centered on China. On Wednesday, he paused his arbitrary and irrational imposition of high tariffs on nearly every country—except China. Though Trump may not realize it, his theatrical escalation of tariffs on China, which he raised to 145 percent, will likely be a gift to Xi.

Yes, Beijing will face difficulties in the short term—perhaps even the long run—but Trump’s behavior distracts Chinese people from Xi’s own shortcomings and lends force to Beijing’s long-standing propaganda about the superiority of its political system and Washington’s villainous designs in trying to keep China down.

To the world at large, China now looks like a more moderate force in the international order oriented toward stability and the status quo. If a country has to choose a superpower to hitch its wagon to, China may loom as the preferable option.

Trump’s extreme measures against Beijing have opened avenues for rapprochement between China and its ordinarily distrusting neighbors, Japan and South Korea, and between China and Europe. Trump’s sudden need, amid deflating stock and bond markets, to prove his touted ability to strike deals has also probably enhanced Tokyo’s and Seoul’s negotiating power vis-à-vis his administration. Such is the tactical price that Washington will pay for waging a reckless economic war and failing to rein in a president so foolish and drunk on power as to boast that other leaders are dying to kiss his ass.

Why does Trump possibly think this is worth it? As commentators frequently point out, much of Trump’s worldview was forged in the 1970s and ’80s, the waning era of U.S. industrial preeminence. Back then, Trump first blamed Japan and then China for “stealing” U.S. jobs, production, and ideas. For Trump, Washington’s position atop the hierarchy of nations seems to be about nostalgia, yes, but also birthright. And he seems to think that by punishing others through tariffs, he can restore what was supposedly taken from the United States.

This badly misunderstands not only basic economics, but also world history. It is true that China has likely stolen intellectual property from abroad—from some of the technology in its impressive high-speed trains to the designs of its fighter jets—and devised ways to protect its economy from competition during its recent decades of stirring growth. However, Trump seems unaware that rising powers have done this throughout the modern era, including the United States in the 19th century.

But China’s leadership in automobiles, transportation, renewable energy, and robotics—and its increasingly close peer competition with the United States in artificial intelligence and space exploration—cannot just be explained away by theft. What Trump does not realize is that most of China’s accomplishments have come from the hard work and sacrifice of its people, along with continuous and purposeful national reinvention. In industry, this has involved identifying frontier fields, such as biomedicine and robotics, and investing heavily in them. And that has been supported by equally concerted pushes to improve higher education and make it more widely available.

Bad emperors are not only self-sure and impulsive. They also tend to be badly informed. That is because by the time they have fully subjugated their own political party and surrounded themselves with yes-men, they are rarely exposed to information that contradicts their views.

Trump has conflated his sense of his own invincibility with that of the United States. Because no one at home has been able to resist him, he now imagines that no one in the world can, either—even when members of his administration make contemptuous statements about China that flirt with racism. Vice President J.D. Vance said last week that Americans shouldn’t borrow from “Chinese peasants.” On Sunday, U.S. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick dismissed the Chinese factories that have made the global smartphone revolution possible as places where hordes of laborers do little more than “[screw] in little screws.”

Meanwhile, U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said this week that China’s business model is broken and “can’t survive” without U.S. markets. (Never mind that China’s exports to the United States as a portion of its global exports have steadily declined from a high of 42 percent in the late 1990s to around 13 percent today.) Bessent imagines a world in which Beijing would be amenable to Washington dictating: “You rebalance. You consume more, manufacture less. We’re going to consume less and manufacture more. … We’re going to level the playing field by a lot.”

This hubristic remark, made by a man often portrayed as the most sober of Trump’s advisors, is stunning in its naivete. It reflects Trump’s nostalgia for an all-powerful U.S. past—a time of deals such as the 1985 Plaza Accord, an agreement that seemingly at the stroke of a pen realigned the world’s major currencies in an effort to reduce the U.S. trade deficit with West Germany and a then-formidably competitive Japan.

But even a China that has started to slow down economically and shrink demographically is quite unlike the Japan of the 1980s, a far smaller country that depended on trade with the United States and relied on it for security. Not only is China roughly 11 times more populous, but in little more than a generation, it has also become the leading trading partner of most countries, a greater source of finance capital than the World Bank, and a military power of the first rank.

“China is an ancient civilization and a land of propriety and righteousness,” China’s Foreign Affairs Ministry said in a recent statement. “We do not provoke trouble, nor are we intimidated by it. Pressuring and threatening are not the right way in dealing with China. China has taken and will continue to take resolute measures to safeguard its sovereignty, security, and development interests.”

Rhetoric aside, this sober statement from Beijing is basically right. The United States will not be able to intimidate China on the basis of tariffs, nor through a bad imperial president’s exaggerated sense of his own power and the nation’s capabilities. It must look at its own weaknesses—not with misplaced nostalgia for a past that is never coming back, but with a positive and demanding agenda for the future.

The post Trump’s Tariffs Are a Gift to Xi appeared first on Foreign Policy.