Fox host admits layoffs hit highest point in decades under Trump

Layoffs in the United States have surpassed 1.1 million in 2025, according to a new report, and even one Fox...

Fresh Pic Shows Donald Trump’s Troubled Hand Is Not Getting Better

Donald Trump’s problematic right hand appeared battered and swollen during an appearance on Thursday, which saw the president wear a...

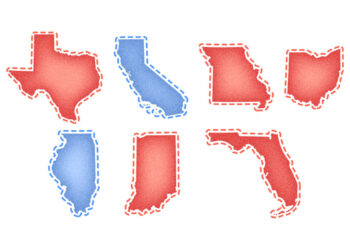

Mapping where the redistricting fight stands and where it’s headed

The redistricting arms race sparked by President Donald Trump’s push to draw new congressional lines in Texas has both parties...

‘Unbelievable’: Trump under seige over pricey fixation while cost of living spikes

The White House reportedly will be submitting plans for President Donald Trump’s $300 million ballroom to a federal planning commission...

Stephen A Smith launches tirade on ‘The View’ over Sen. Mark Kelly’s video urging troops to ignore illegal orders

The co-hosts of ABC’s “The View” tore into ESPN host Stephen A. Smith on Thursday for condemning Sen. Mark Kelly, D-Ariz., for...

Ben Stiller, Simu Liu defend star Paul Dano after Quentin Tarantino diss

Hollywood stars are rallying behind “The Batman” star Paul Dano after director Quentin Tarantino slammed the actor’s abilitiesin a podcast...

Investigators Find Human Remains Buried at a San Diego Home

Criminal investigators equipped with shovels and a specially trained dog descended on a home in San Diego this week and...

Trump admin breached a ‘red line you cannot cross’: ex-JAG officer

One retired Judge Advocate General Corps (JAG) officer says officials in President Donald Trump’s Pentagon may have been aware they...

Former USIP Lawyer on DOGE: ‘Brass Knuckles on an Authoritarian Fist’

George Foote still has vivid memories of the day operatives from Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency arrived at...

Second Strike Scrutiny Obscures Larger Question About Trump’s Boat Attacks

As Congress parses the details of a follow-on strike that killed shipwrecked survivors of President Trump’s first boat attack on...