Luka Doncic and Lakers dominate Curry-less Warriors to halt losing streak

SAN FRANCISCO — The Lakers seemingly lost their mojo after the All-Star break, with three consecutive losses leaving them in search of...

MAGA-Curious CBS Boss Posts Eye-Popping Reaction to Iran War

Bari Weiss couldn’t resist hitting repost. The MAGA-curious CBS News editor-in-chief amplified a clip of Iranian-American journalist and activist Masih...

Israel bombards Iranian ballistic missile, air defense sites in new round of strikes

Israel’s military bombarded Iranian ballistic missile and air defense sites in a new round of strikes Sunday morning, with blasts reported in Tehran amid...

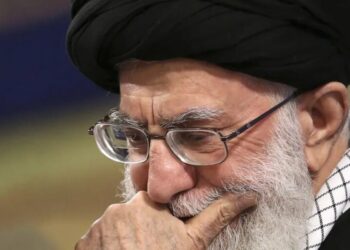

Iranian Supreme Leader Khamenei dies after major attack by Israel and the U.S., Iranian state media confirms

Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei died following a major attack by Israel and the United States, Iranian state media...

American, Israeli strike on Iran came 2 days after latest talks, as theocracy struggled with nationwide protests

The U.S. and Israel attacked Iran on Saturday in a massive operation, and Tehran hours later said Supreme Leader Ayatollah...

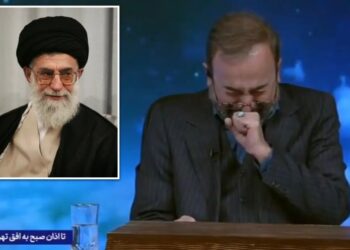

Iranian anchor sobs on state TV as he announces Khamenei killed in ‘criminal’ US-Israeli airstrikes

This is the moment that an Iranian anchor sobbed on state TV as he announced the death of Supreme Leader...

Marjorie Taylor Greene rips Iran strikes as Trump betraying America First: ‘It’s always a lie and it’s always America Last’

President Donald Trump, whose fierce denunciation of military adventurism abroad fueled his unlikely rise to the top of the Republican...

Russia accuses America of ‘pre-planned and unprovoked act of armed aggression’ against Iran

How long will it last? Will it grow? What will the conflict and the reported death of Iran’s Supreme Leader...

Seth Rollins Returns at WWE Elimination Chamber

Seth Rollins was on a roll in 2025. WWE World Heavyweight Champion, the leader of The Vision — he was...

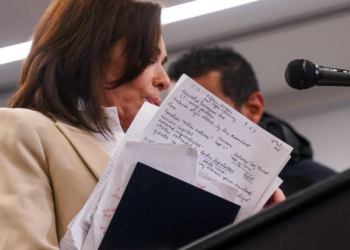

Kamala Harris doesn’t want regime change in Iran: ‘Dangerous and unnecessary’

Kamala Harris has joined other far-left Dems by stating that she doesn’t support regime change in Iran. The former vice...